Tibetan Plateau

The Highlands of Tibet, officially Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (Tibetan བོད་ས་མཐོ། Wylie bod sa mtho, Chinese 青藏高原, pinyin Qīng-Zàng gāoyuán), is a landscape and ecoregion in East Asia and southwestern China, respectively, that forms the least mountainous center of the Mass Uplift of High Asia as the highest plateau on Earth. The term roof of the world is often used for the Tibetan Plateau.

The total area of the region is given by Burga, Klötzli and Grabherr as 2.16 million km²; this is about the size of Greenland with a west-east extension of about 1600 km and a north-south extension of about 800 km. In general, figures between 2 million and 2.5 million km² can be found, whereby all figures include the entire peripheral mountains.

About one third of the ecoregion lies above 5000 m. Since the boundary of the area is drawn differently, the data on the highest mountain of the highlands are inconsistent: If the marginal ranges of the highlands are included completely, it is the 8849 m high Mount Everest, which is at the same time the highest mountain in High Asia and on earth. In most cases, only the canopies of the marginal ranges pointing towards the centre are included. In this case it is the 7206 m high Noijinkangsang in the northern slope of the Himalaya. If only the central plateau is considered, it is the 7162 m high Nyainqêntanglha in the Transhimalaya.

The vegetation of the highlands consists largely of species-poor mats, highland steppe and cold deserts. The use is limited to a very extensive, mostly still nomadic pastoral economy in the lower regions, which has existed for thousands of years.

In the western highlands there are only drainless waters, which are also often salty and dry up quickly. Nevertheless, the headwaters of the great rivers Indus, Brahmaputra, Salween, Mekong, Yangtze and Yellow River are located here.

Due to the low precipitation climate, only the mountain ranges at the edge of the plateau show weak glaciations.

At least on paper, large parts of the highlands are protected.

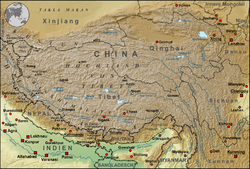

Map of the Tibetan Plateau

In Amdo, in the northeast of the Tibetan highlands...

Geography

The highlands are divided into the western Changthang in the Tibet Autonomous Region (AGT) of the People's Republic of China, as well as the central Yarmothang highlands largely located in the Chinese province of Qinghai, the island-like Qaidam basin in Qinghai to the northeast, and the mountainous lands in the transition to the border of Sichuan province. It encompasses most of historic Tibet as well as what is now the Chinese Autonomous Region of Tibet (AGT).

In the north, the hilly to medium mountainous plateau is bordered by the mountain ranges of the Altun-Qilian-Kunlun. In the west the Karakorum Mountains and in the south the Transhimalaya - or depending on the author the Himalaya - form the borders. In the east, the Tanggula Shan and the Bayan Har Mountains are understood as parts of the highlands, while the mountain ranges of the (extended) Hengduan Shan form the eastern border.

Climate

Although the entire highlands of Tibet lie in the subtropical climate zone, the distinct high altitude climate results in extrazonal vegetation that is more reminiscent of cold temperate to polar climates. In contrast, however, there are some crucial differences to be noted:

The climate is characterized by high temperature differences between day and night and by rapid, strong weather changes. The average temperature in Changtang varies, being higher in the south and west than in the north and east. At Lake Aru Co in Rutog County, the average temperature is -8 degrees Celsius, while in Shuanghu in the northeast it is -24 degrees Celsius. The annual temperature fluctuations are not as extreme as the daily ones. For example, temperatures in the west can easily drop from +20 to -40 degrees Celsius. In the northeast, in Shuanghu County, temperatures do not climb above freezing even in July. The average temperature is then about -10 degrees Celsius.

The location in subtropical latitudes and high sea level leads to extremely strong solar radiation, so that the temperatures in summer are about 25 Kelvin higher than they would be without these factors (see mass elevation effect). Equally extreme is the nocturnal radiation, which can bring frosty nights even in summer. The northern half of the highlands is completely permafrost area, in the southern half this only applies to the mountains.

The shielding by the peripheral mountains results in a very dry climate, so that it rarely rains or a snow cover develops. Indirectly, this can be seen in the lack of white winter coat in the animal kingdom (as is known, for example, from the rock ptarmigan and the snow hare of other cold climates). Most precipitation occurs in summer: usually heavy thundershowers during the day and prolonged drizzle and sleet at night with westerly winds. The enormous day/night differences lead to frequent thunderstorms (annual average: 90 days), often associated with squalls and, in some regions, sandstorms. Towards the west and north, the annual mean precipitation drops to 20 to 80 mm.

Search within the encyclopedia