Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648 was a conflict for hegemony in the Holy Roman Empire and in Europe that began as a religious war and ended as a territorial war. In this war, the Habsburg-French antagonism on the European level and the antagonism between the emperor and the Catholic League on the one hand and the Protestant Union on the other were unleashed on the imperial level. Together with their respective allies, the Habsburg powers of Austria and Spain fought out not only their territorial but also their dynastic conflicts of interest with France, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden, mainly on the soil of the Empire. As a result, a number of other conflicts were closely linked to the Thirty Years' War:

- the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) between the Netherlands and Spain,

- the Upper Austrian Peasants' War (1626)

- the War of the Mantuan Succession (1628-1631) between France and Habsburg,

- the French-Spanish War (1635-1659)

- the war for supremacy in the Baltic Sea area (Torstensson War) (1643-1645) between Sweden and Denmark.

The trigger of the war is considered to be the Prague defenestration of 23 May 1618, with which the uprising of the Protestant Bohemian estates broke out openly. The uprising was mainly directed against the new Bohemian King Ferdinand of Styria (who intended to recatholicize all lands of the Bohemian Crown), but also against the then Roman-German Emperor Matthias.

In total, four conflicts followed each other in the 30 years from 1618 to 1648, which historians have called the Bohemian-Palatinate War, the Danish-Lower Saxon War, the Swedish War and the Swedish-French War, according to the respective opponents of the Emperor and the Habsburg powers. Two attempts to end the conflict (the Peace of Lübeck in 1629 and the Peace of Prague in 1635) failed because they did not take into account the interests of all those directly or indirectly involved. This was not achieved until the Pan-European Peace Congress of Münster and Osnabrück (1641-1648). The Peace of Westphalia redefined the balance of power between the emperor and the imperial estates and became part of the constitutional order of the empire in force until 1806. It also provided for cessions of territory to France and Sweden and the withdrawal of the United Netherlands and the Swiss Confederation from the imperial union.

On 24 October 1648 the war, whose campaigns and battles had taken place mainly on the territory of the Holy Roman Empire, ended. The acts of war and the famines and epidemics they caused had devastated and depopulated whole swathes of land. In parts of southern Germany, only a third of the population survived. After the economic and social devastation, some of the areas affected by the war took more than a century to recover from its effects. Since the war took place predominantly in German-speaking areas that are still part of Germany today, experts believe that the wartime experiences led to the anchoring of a war trauma in the collective memory of the population.

"The Gallows Tree", from the 18-part etching cycle "The Great Terrors of War" (Les Grandes Misères de la guerre), after Jacques Callot (1632). The illustration shows the execution of thieves ("Voleurs infames et perdus") and presumably also marauders, who are throwing dice for their lives (in the illustration on the right). The measure is not an arbitrary act, but takes place in the presence of clergymen and corresponds to the martial law of the time, for the maintenance of military discipline.

History and causes

In the run-up to the Thirty Years' War, a multifaceted field of tension had built up in Europe and the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, consisting of political, dynastic, confessional and domestic antagonisms. The causes go back a long way in time.

balance of power in Europe

In the period leading up to the Thirty Years' War, there were three main areas of conflict: western and north-western Europe, northern Italy and the Baltic region. In Western and Northwestern Europe and in Upper Italy, the dynastic conflicts were fought between the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs and the French king as well as the Dutch, who were striving for independence, while in the Baltic Sea region Denmark and Sweden fought for supremacy as possible great powers.

Dominant in western and northwestern Europe was the conflict between France and Spain, which in turn arose from the dynastic opposition of the Habsburgs and French kings. Spain was a major European power with possessions in southern Italy, the Po Valley, and the Netherlands. The scattered Spanish bases meant that there could hardly be a war in western and northwestern Europe that did not affect Spanish interests. France, in turn, faced Spanish countries in the south, north, and southeast, leading to the French "encirclement complex." Because of their many violent disputes, France and Spain upgraded their armies. In addition to financial difficulties, Spain also had to fight the rebellion in the Netherlands from 1566, but this ended de facto in 1609 with the independence of the United Netherlands and a truce limited to twelve years.

The conflict in Western Europe could have escalated into a major European war in the Jülich-Klev succession dispute when the Duke of Jülich-Kleve-Berg died and the claimants asserted their claims, including Elector Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg and Count Palatine Wolfgang Wilhelm of Neuburg. The war took on international significance with the intervention of Henry IV of France, who supported the princes of the Protestant Union and in return demanded their aid in a war against Spain. The assassination of Henry IV in 1610 ended the French involvement in the Lower Rhine for the time being.

In Upper Italy, in addition to many small principalities, there was the Duchy of Milan, which was directly ruled by the Spanish. Neighbouring powers of European rank were the Pope and the Republic of Venice, with the Curia in Rome dominated by pro-French, pro-Spanish and pro-emperor cardinals, while Venice's interests lay more in the Mediterranean and on the Adriatic coast than in Italy. The most influential forces in northern Italy were Spain and France, the latter striving to weaken Spanish power and itself gain dominance in the region. Both powers tried to win over the local princes with their envoys. The dukes of Savoy experienced this particularly clearly, as the duchy had a strategically important position: with the Alpine passes and fortresses of Savoy, the important supply route of the Spanish troops to the Netherlands could be controlled.

The three main actors of the wars in the Baltic region were Poland, Sweden and Denmark. Poland and Sweden were ruled for a time in personal union by Sigismund III, who prevented the spread of Protestantism in Poland, which was therefore one of Habsburg's allies during the Thirty Years' War. In 1599 he was deposed as Swedish king by a revolt of the nobility. As a result, the Lutheran faith became established in Sweden and a long-lasting war broke out between Poland and Sweden. The first campaigns of the new Swedish king, Charles IX, were initially unsuccessful and encouraged his Swedish rival, Christian IV of Denmark, to attack. Denmark was less populous than either Sweden or Poland, but through possession of Norway and southern Sweden was in sole control of the Öresund, earning it large customs revenues. Charles IX of Sweden, on the other hand, founded Gothenburg in 1603, hoping thereby to collect some of the customs revenues from the Öresund. Therefore, when Christian IV started the Kalmar War in 1611, Charles IX expected to attack Gothenburg, but instead the Danish army marched on Kalmar by surprise and captured the city. In 1611 Charles IX died and his son Gustav II Adolf had to pay a high price for peace with Denmark: Kalmar, northern Norway and Ösel fell to Denmark, plus war tributes of one million Reichsmarks. In order to be able to pay this sum, Gustav Adolf went into debt with the United Netherlands. These war debts weighed heavily on Sweden and weakened its foreign policy position. Denmark, on the other hand, had become a Baltic power as a result of the war, and Christian IV therefore considered himself a great general on the one hand and believed he had enough money for further wars on the other.

Confessional contrasts

After the first phase of the Reformation, which had divided Germany along confessional lines, the Catholic and Protestant sovereigns initially tried to find a constitutional order acceptable to both sides and a balance of power between the confessions in the empire. In the Augsburg Religious Peace of September 25, 1555, they finally agreed on the jus reformandi, the right of reformation (later summarized as cuius regio, eius religio, Latin for: whose territory, whose religion; "rule determines the confession"). Accordingly, the sovereigns had the right to determine the confession of the resident population. At the same time, the jus emigrandi, the right to emigrate, was introduced, which allowed persons of another denomination to emigrate. However, the right of the free imperial cities to reformation remained unclear, because the Augsburg Religious Peace did not specify how they were to change confession. Since then, the Catholic and Lutheran confessions of faith were recognized as having equal rights, but not the Reformed confession.

Also included was the Reservatum ecclesiasticum (Latin for: "spiritual reservation"), which guaranteed that possessions of the Catholic Church of 1555 would remain Catholic. Should a Catholic bishop convert, he would lose his see and a new bishop would be elected. This arrangement also ensured majority rule in the Electoral College, in which four Catholic and three Protestant electors faced each other. The ecclesiastical reservation was tolerated by the Protestant princes only because the Declaratio Ferdinandea (Latin for: "Ferdinandian Declaration") assured that already reformed cities and estates in ecclesiastical territories would not be forcibly converted or forced to emigrate.

Intensification of the conflict situation and decay of the political order in the empire

Although the provisions of the Augsburg Religious Peace prevented the outbreak of a major religious war for 60 years, disputes arose over its interpretation, and a confrontational attitude on the part of a new generation of rulers contributed to the intensification of the conflict situation and the decay of the political order. However, due to the lack of military potential of the adversaries, the conflicts were largely non-violent for a long time.

One effect of the Augsburg Religious Peace was a development known today as "confessionalization". In this process, the sovereigns attempted to create religious uniformity and to shield the population from different religious influences. The Protestant princes feared a split in the Protestant movement, which might thereby lose its protection under the Augsburg Religious Peace, and used their position as emergency bishops to discipline the clergy and the population in accordance with their confession (social disciplining). As a result, bureaucratization and centralization occurred, and the territorial state was strengthened.

Peace in the empire came increasingly under threat in the decades following the Peace of Augsburg, when the rulers, theologians and jurists who had lived through the Schmalkaldic War stepped down and their successors in office adopted a more radical policy, ignoring the consequences of an escalation of the conflict. This radicalization was evident, among other things, in the handling of the "ecclesiastical reservation," for while Emperor Maximilian II still issued "feudal indults" to Protestant nobles with Catholic bishoprics (i.e., temporarily enfeoffed them so that they remained capable of acting politically, even though they were not proper bishops for lack of papal confirmation), his successor Rudolf II ended this practice. Consequently, Protestant administrators without enfeoffments and indults were no longer entitled to vote at imperial diets.

This became problematic in 1588, when the Imperial Diet was to form a visitation deputation. The Visitationsdeputation was a court of appeal: violations of imperial law (such as the confiscation of goods of the Catholic Church by Protestant sovereigns) were heard before the Reichskammergericht. Appeals were heard before the Imperial Chamber Court Deputation, or Visitationsdeputation for short. This deputation was filled in rotation, and in 1588 the Archbishop of Magdeburg should have been a member. However, since the Lutheran administrator of Magdeburg, Joachim Friedrich of Brandenburg, was not entitled to vote at the Diet without an indult, he could not participate in the visitation deputation, which was therefore unable to act. Rudolf II therefore postponed the formation of the deputation until the next year, but no agreement could be reached in 1589 either, nor in the following years, which is why an important revision institution no longer functioned.

Due to the increasing number of revision cases, including above all the confiscation of monasteries by territorial lords, the competence of the visitation deputation was transferred to the imperial deputation in 1594. When in 1600 a Catholic majority emerged in the Imperial Deputation in four revision cases (monastery secularizations by the free imperial city of Strasbourg, the Margrave of Baden, the Count of Oettingen-Oettingen and the Imperial Knight of Hirschhorn), the Electoral Palatinate, Brandenburg and Brunswick left the committee and thus paralyzed the Imperial Deputation. The failure of the institutions of revision weakened the Imperial Chamber Court; the princes preferred to have their disputes heard by the Imperial Court, which was thus strengthened. Because of its counter-Reformation stance, the strengthening of the Imperial Court also meant a strengthening of the Catholic side in the Empire.

Due to the strengthening of the states, the confrontational policy of the new rulers, the paralysis of the Imperial Chamber Court as an instance of peaceful conflict resolution in the Empire and the strengthening of the Catholic princes by the Imperial Court Council, hostile princely groupings were formed. As a result, and in reaction to the cross and flag clash in the town of Donauwörth, the Electoral Palatinate withdrew from the Imperial Diet. A Reichstag resolution on the Turkish tax therefore did not come about and the Reichstag, as the most important constitutional body, was inactive.

On 14 May 1608, under the leadership of the Electoral Palatinate, the Protestant Union was founded, to which 29 imperial states soon belonged. The Protestant princes regarded the Union primarily as a protective alliance, which had become necessary because all imperial institutions such as the Imperial Chamber Court were blocked as a result of the confessional antagonisms, and they no longer regarded the protection of peace in the Empire as a given. The Protestant Union only became politically influential through its connection to France, because the Protestant princes wanted to gain respect from the Catholic princes through a military coalition with France. France, for its part, tried to make the Union its ally in the fight against Spain. After the death of the French King Henry IV in 1610, a coalition with the Netherlands was sought, but the States General did not want to be drawn into internal conflicts within the empire and left it at a defensive alliance concluded in 1613 for 12 years.

As a counterpart to the Protestant Union, Maximilian I of Bavaria founded the Catholic League on July 10, 1609 to secure Catholic power in the Empire. Although the Catholic League was in the better position, but unlike the Protestant Union, there was no powerful leader, but the rank struggles, especially between Maximilian I of Bavaria and the Elector of Mainz hindered the Catholic League again and again.

Cross and flag clashes in Donauwörth in 1606 and 1607: The violent clashes contributed significantly to the aggravation of confessional tensions

Frans Hogenberg: The Great Market and the City Hall during the Spanish Furies in Antwerp

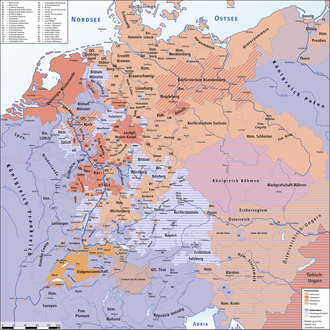

The Confessions in Central Europe around 1618

_-_DE.svg.png)

Central Europe on the eve of the Thirty Years' War. Habsburg possessions: Austrian line (Tyrol to Hungary in the east). Spanish line (Milan to Flanders in the west)

War History

Outbreak of war

→ Main article: Estates Revolt in Bohemia (1618)

The war was actually triggered by the Estates Revolt in Bohemia in 1618, which had its roots in the dispute over the Letter of Majesty issued by Emperor Rudolf II in 1609, which had guaranteed the Bohemian Estates religious freedom. His brother Matthias, who reigned from 1612, recognised the Letter of Majesty when he came to power, but tried to reverse the concessions made to the Bohemian estates by his predecessor. When Matthias ordered the closure of the Protestant church in Braunau, banned the practice of the Protestant religion altogether, interfered in the administration of the towns, and answered a protest note from the Bohemian estates that followed in March 1618 with a ban on meetings of the Bohemian Diet, nobles armed with swords and pistols stormed the Bohemian Chancellery in Prague Castle on May 23, 1618. At the end of a heated discussion with the imperial deputies Jaroslav Borsita of Martinic and Wilhelm Slavata, these two and the chancery secretary Philipp Fabricius were thrown out of the window (Second Defenestration of Prague). This act was supposed to seem spontaneous, but it was planned from the beginning. Although the three victims survived, the attack on the imperial deputies was also a symbolic attack on the emperor himself and therefore amounted to a declaration of war. The emperor's subsequent punitive action was thus deliberately provoked.

Bohemian-Palatinate War (1618-1623)

Bohemian-Palatinate War (1618-1623)

Pilsen - Vražda - Sablat - White Mountain - Mingolsheim - Wimpfen - Höchst - Fleurus - Stadtlohn

War in Bohemia

After the revolt, the Bohemian estates formed a thirty-member directorate in Prague to secure the new power of the nobility. Its main tasks were to draw up a constitution, elect a new king and provide military defence against the emperor. In the summer of 1618, the first battles began in southern Bohemia as both sides sought allies and prepared for a major military strike. The Bohemian rebels were able to win over Frederick V of the Palatinate, head of the Protestant Union, and Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy. The latter financed the army under Peter Ernst II of Mansfeld to support Bohemia.

The German Habsburgs, on the other hand, engaged the Count of Bucquoy, who set out on march on Bohemia at the end of August. However, the campaign to Prague was stopped for the time being by Mansfeld's troops, who captured Pilsen at the end of November. The imperial forces had to retreat to Budweis.

Initially, it seemed that the uprising of the Bohemian estates would be successful. The Bohemian army under Heinrich Matthias von Thurn first forced the Moravian estates to join the uprising, then invaded the Habsburgs' Austrian homelands and stood before Vienna on 6 June 1619. But the Count of Bucquoy succeeded in defeating Mansfeld at Sablat, so that the Directory at Prague had to recall Thurn to the defence of Bohemia. In the summer of 1619 the Bohemian Confederation was formed; the Bohemian Assembly of Estates deposed Ferdinand as King of Bohemia on August 19 and elected Frederick V of the Palatinate as the new king on August 24. At the same time, Ferdinand travelled to Frankfurt am Main for the election, where the electors unanimously crowned him Roman-German Emperor on 28 August.

With the Treaty of Munich of 8 October 1619, Emperor Ferdinand II succeeded in persuading the Bavarian Duke Maximilian I to enter the war, making major concessions, but Ferdinand still came under pressure in October when the Prince of Transylvania Gabriel Bethlen, allied with Bohemia, laid siege to Vienna. Bethlen soon withdrew, however, fearing that an army recruited by the emperor in Poland might stab him in the back. The following year, the lack of support for the Protestant insurgents became apparent, and they became increasingly defensive. A meeting of all Protestant princes called by Frederick at Nuremberg in December 1619 was attended only by members of the Protestant Union, while the emperor was able to rally the Protestant princes loyal to the emperor in March 1620. Electoral Saxony was promised Lusatia for its support. With the Treaty of Ulm, the Catholic League and the Protestant Union concluded a non-aggression agreement, so that Frederick could no longer expect any help. Therefore, in September, the League army was able to march unhindered into Bohemia via Upper Austria, while Saxon troops occupied Lusatia. Even Bethlen's soldiers could not stop the enemy. On November 8, 1620, the Battle of White Mountain took place near Prague, in which the Bohemian army of the Estates was severely defeated by the commanders Buquoy and Johann T'Serclaes of Tilly. Frederick was forced to flee from Prague via Silesia and Brandenburg to The Hague, and sought allies in northern Germany. Silesia, on the other hand, broke away from the Bohemian Confederation. In January Emperor Ferdinand imposed the imperial ban on Frederick. Finally, between January and March 1621, the Danish king Christian IV had summoned the Protestant dukes of Lüneburg, Lauenburg and Brunswick, the envoys of England, Holland, Sweden, Brandenburg and Pomerania, as well as the expelled winter king, to the "Segeberger Convent" at Siegesburg Castle in Holstein, in order to decide on joint measures against the Catholic emperor. After futile deliberations, the Protestant Union finally dissolved itself in April 1621.

After the victory at Prague, the emperor held a criminal court in Bohemia: 27 people were subsequently tried and executed for lese majeste. To push back Protestantism in Bohemia, Ferdinand expelled 30,000 families and confiscated 650 noble estates as reparations, which he distributed to his Catholic creditors to pay off his debts.

War in the Electoral Palatinate

Already in the summer of 1620, the Spanish commander Ambrosio Spinola, coming from Flanders, conquered the Palatinate on the left bank of the Rhine, but retreated back to Flanders in the spring of 1621. A garrison of 11,000 soldiers remained in the Palatinate. The remaining Protestant army commanders, Christian of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, called the "great Halberstadter," and Ernst of Mansfeld, as well as Margrave George Frederick of Baden-Durlach, moved into the Palatinate from different directions in the spring of 1622. In the Palatine hereditary lands of the "Winter King", the Protestant troops were initially able to win the battle of Mingolsheim (27 April 1622). In the following months, however, they suffered heavy defeats because, although they outnumbered the Emperor's loyalists, they were unable to unite. The Baden troops were crushed at the Battle of Wimpfen (6 May 1622), and at the Battle of Höchst Christian of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was defeated by the League army under Tilly. Christian of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel then joined Ernst of Mansfeld in Dutch service, where the two armies departed. On the march they met a Spanish army, over which they won a Pyrrhic victory at the Battle of Fleurus (29 August 1622). From the summer of 1622 the Palatinate on the right bank of the Rhine was occupied by league troops, and Frederick V lost the electorship on 23 February 1623, which was transferred to Maximilian of Bavaria. Christian of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel suffered another devastating defeat at Stadtlohn, and his decimated troops were henceforth no longer a serious opponent for the imperials. The Upper Palatinate fell to Bavaria and was Catholicized by 1628. Also in 1628, the electoral dignity of the Bavarian dukes became hereditary, as did the possession of the Upper Palatinate. In return, Maximilian forgave Emperor Ferdinand the reimbursement of 13 million florins in war costs. The territorial expansion of Bavaria and the transfer of a Protestant electoral dignity to a Catholic power profoundly changed the power structure in the empire and laid the foundation for the subsequent expansion of the war.

Restart of the Eighty Years War

→ Main article: Eighty Years' War

When the twelve-year truce between the Netherlands and Spain expired in 1621, the Dutch War of Independence also began again. Spain had used the period of peace to strengthen its military power so that it could threaten the Netherlands with an army of 60,000 men. In June 1625, after almost a year of siege, it succeeded in forcing the Dutch city of Breda to surrender, but a renewed financial shortage on the part of the Spanish crown hindered further operations by the Flemish army and thus prevented the complete conquest of the Dutch Republic.

Danish-Lower Saxon War (1623-1629)

Danish-Lower Saxon War (1623-1629)

Dessau - Lutter - Wolgast

After the Emperor's victory over the Protestant princes in the Empire, France again pursued an anti-Habsburg policy from 1624. To this end, the French king Louis XIII not only concluded an alliance with Savoy and Venice, but also initiated an alliance of the Protestant rulers in northern Europe against the Habsburg emperor. In 1625, the Hague Alliance was formed between England, the Netherlands and Denmark. The aim was to jointly maintain an army led by Christian IV of Denmark to secure northern Germany against the emperor. Christian IV promised to require only 30,000 soldiers, most of whom were to be paid for by the Lower Saxon Imperial Circle, of which Christian was a voting member as Duke of Holstein. He thus prevailed over the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf, who demanded 50,000 soldiers. Christian's main motivation for entering the war was to win Verden, Osnabrück and Halberstadt for his son.

Christian immediately recruited an army of 14,000 men and, at the county assembly in Lüneburg in March 1625, tried to persuade the county estates to finance a further 14,000 mercenaries and to elect him county governor. The Estates, however, did not want a war and therefore made it a condition that the new army would only serve to defend the county and would therefore not be allowed to leave the county territory. The Danish king did not adhere to the regulation and occupied Verden and Nienburg, cities that belonged to the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Imperial Circle.

In this threatening situation, the Bohemian nobleman Albrecht von Wallenstein offered the emperor to initially raise an army on his own account. In May and June 1625, the imperial councillors discussed the offer. The main concern was to provoke a new war by raising an army. However, since the majority of the councillors thought an attack by Denmark was likely and wanted to arm themselves against it, Wallenstein was elevated to the rank of duke in Nikolsburg, Moravia, in mid-June 1625. In mid-July he received his patent to the first generalate and orders to raise an army of 24,000 men, reinforced by additional regiments from other parts of the empire. By the end of the year Wallenstein's army had thus grown to 50,000 men. Wallenstein moved into his winter quarters in Magdeburg and Halberstadt, thus blocking shipping on the Elbe, while the League army under Tilly continued to camp in eastern Westphalia and Hesse.

With his ally Ernst von Mansfeld, Christian planned a campaign that would be directed first against Thuringia and then against southern Germany. Like the Bohemians and Frederick of the Palatinate before him, however, Christian waited in vain for significant support from other Protestant powers and, moreover, found himself facing not only the army of the League but also Wallenstein's army in the summer of 1626. On August 27, 1626, the Danes suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Tilly in the Battle of Lutter am Barenberge, which cost them the support of their German allies.

On April 25, 1626, Wallenstein had already defeated Christian's ally Ernst von Mansfeld at the Battle of the Elbe Bridge in Dessau. Mansfeld then once again succeeded in raising an army, with which he moved south. In Hungary he intended to unite his troops with those of Bethlen, and then to attack Vienna. But Wallenstein pursued the mercenary leader and finally forced him to flee. Mansfeld died shortly thereafter near Sarajevo. In the summer of 1627, Wallenstein advanced to northern Germany and the Jutland peninsula in a few weeks. Only the Danish islands remained unoccupied by the imperials, as they did not have ships. In 1629 Denmark concluded the Peace of Lübeck and left the war.

The Protestant cause in the Empire seemed lost. Like Frederick of the Palatinate in 1623, the Dukes of Mecklenburg, allied with Denmark, were now declared deposed. The Emperor transferred their sovereignty to Wallenstein in order to pay his debts to him. Also in 1629, Ferdinand II issued the Edict of Restitution, which provided for the restitution of all ecclesiastical possessions confiscated from Protestant princes since 1555. The edict marked both the high point of imperial power in the empire and the turning point of the war, for it rekindled the already broken resistance of the Protestants and brought them allies whom the emperor and the League were ultimately no match for.

War of the Mantuan Succession

→ Main article: War of the Mantuan Succession

During this period, the War of Succession broke out in Italy over the Duchy of Mantua, in which Ferdinand II supported the Spanish and the Duke of Guastalla against France and the Duke of Nevers with an army. Despite the military success that led to the conquest and plunder of Mantua by imperial soldiers in July 1630, the emperor and Spain were unable to achieve their political goals. At the same time, the emperor subsequently lacked these troops in the German theater of war.

Swedish War (1630-1635)

Swedish War (1630-1635)

Frankfurt (Oder) - Werben - Breitenfeld - Rain - Wiesloch - Zirndorf - Lützen - Hessisch Oldendorf - Regensburg - Nördlingen

The widely used designation chosen here for the relatively short phase of the war as the "Swedish War" is, strictly speaking, arbitrary. Actually, the Swedish War dragged on continuously for about 20 years, counted from the arrival of the Swedes in 1630 until their withdrawal in 1650. This long period was interrupted for the Swedes only once briefly after the Battle of Nördlingen in 1634, when the position of the Swedes collapsed for a few months. Other warring parties also experienced similar collapses - on the imperial side even several times - without this changing the previously customary designations of the phases of the war.

After Denmark, a Baltic power, had left the Thirty Years' War, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden saw his chance to assert his hegemonic claims in north-eastern Europe. On July 6, 1630, he landed on Usedom with an army of 13,000 men and reinforced his forces with enlistments to 40,000 men. In protracted negotiations with France, he secured a base to finance the planned campaign with the Treaty of Bärwalde, concluded in January 1631. Further months of threats and with the capture of Frankfurt an der Oder in April 1631 were necessary to induce Pomerania, Mecklenburg, Brandenburg and Saxony to sign treaties of alliance with Sweden. During this period, in May 1631, the city of Magdeburg, which had been besieged for months by Catholic League troops under Tilly, was captured. The city was largely destroyed by fires and was almost completely depopulated after more than 20,000 deaths. The event, known as the Magdeburg Wedding, was the largest massacre of the Thirty Years' War and, spread by hundreds of pamphlets and leaflets, became an effective instrument of anti-Catholic propaganda for the Protestants.

On September 17, 1631, the Swedish army under Gustav Adolf met the troops of the Catholic League under Tilly in the Battle of Breitenfeld north of Leipzig. Tilly was devastatingly defeated and was subsequently unable to stop the advance of the Swedes into southern Germany. He was wounded at the battle of Rain am Lech (14-15 April 1632) and retreated to Ingolstadt, where he died on 30 April from the effects of a severe wound, with the word "Regensburg" on his lips. The Swedes attempted to take the strongly fortified Ingolstadt, but failed despite heavy losses. After the siege was broken off, a Swedish army group under Horn pursued Bavarian troops who were on their way to Regensburg. Elector Maximilian had unexpectedly occupied the city by force on April 27, 1632, thus beginning the battle for Regensburg. A Swedish attack was expected, because the Protestant imperial city of Regensburg was regarded as a key fortress on the Danube, which was to protect Vienna and thus Austria from the Swedish attack already feared by Tilly. Instead of attacking Regensburg, however, the main Swedish army under Gustav Adolf pursued the Bavarian Elector Maximilian, who fled from Ingolstadt to Munich and then on to Salzburg. In mid-May 1632, the barely defended royal seat of Munich was taken by the Swedish army. By paying a high tribute of 300,000 talers, the city was able to save itself from plunder. While Gustav Adolf did not tolerate any plundering in the city of Munich, on his way to Munich and during his 10-day stay he had opened the rural regions of Bavaria to systematic plundering by his soldiers.

At the beginning of 1632, Emperor Ferdinand II had already reappointed Wallenstein, who had been dismissed at the Electors' Day in Regensburg in 1630, as commander-in-chief of the imperial troops, because after the great victory of the Swedes at Breitenfeld it was to be expected that Swedish troops and Saxon troops allied with them would now threaten Bohemia and Bavaria. Wallenstein had very quickly raised a new army in Bohemia, had moved with the army to Nuremberg, and had established a large, strongly fortified, and well-supplied camp there. For Gustavus Adolphus' army, which was at Munich in June 1632, this, together with the fickleness of his Saxon allies, threatened the routes of retreat to the north. Gustav Adolf was forced to retreat from Munich to Nuremberg and to engage Wallenstein there. However, in the battle of the Alte Veste west of Nuremberg near Zirndorf on September 3, 1632, Wallenstein did not succeed in defeating the Swedish army, but inflicted such considerable losses that Gustavus Adolphus was forced to withdraw. The subsequent withdrawal of Wallenstein's army to winter quarters in Saxony forced Gustav Adolf to stand by the allied Saxons. He pursued the retreating Wallenstein army and was able to catch up with it near Leipzig at Lützen, but failed to launch the hoped-for surprise attack. The battle of Lützen, which did not begin until the following day, November 16, 1632, due to fog, was initially favorable for Gustavus Adolphus. This changed, however, when the mounted troops under Pappenheim, who had already been dismissed to quarters by Wallenstein but then ordered back, arrived on the battlefield, although Pappenheim was killed soon after arriving. Gustav Adolf also lost his life in a confused situation. After his death became known, Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar seized supreme command of the initially shocked troops while still on the battlefield and successfully ended the battle for the Swedes.

The death of Gustav Adolf was a heavy loss for the Protestants. The Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna took over the regency of Sweden and also the military supreme command. New army structures and new alliances were needed to continue the struggle. Oxenstierna formed the Heilbronn League (1633-1634) with the Protestants of the Franconian, Swabian, and Rhenish imperial districts. The death of Gustavus Adolphus also led to considerable reshuffling of the Swedish army units and to disputes between the army leaders, among whom Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar was able to gain a leading position as a German imperial prince. He occupied Bamberg in February 1633 and intended to occupy the Upper Palatinate with his new "Franconian army" and to conquer this key city in the battle for Regensburg in order to advance from there into Austria. Because of mutinies among the troops due to non-payment of pay, the plans were delayed and Regensburg was not conquered and occupied until November 1633. Wallenstein had failed to prevent the conquest of Regensburg from Bohemia. This ultimately led to the Bavarian Elector Maximilian and especially Emperor Ferdinand II completely losing confidence in Wallenstein and finding ways to have Wallenstein assassinated at Eger on February 25, 1634.

After Wallenstein's death, the Emperor's son, the future Emperor Ferdinand III, was given supreme command of the Imperial army. In a joint operation with the Bavarian Elector and the Bavarian-led army of the Catholic League under the command of Johann von Aldringen, he succeeded in the battle for Regensburg in recapturing this city, which had been occupied by the Swedes in November 1633, in July 1634. The loss of Regensburg, which was almost prevented by a relieving attack by two Swedish armies, which, however, lost much time by the excessive plundering of Landshut, was the beginning of further military failures for the Swedes. Both Swedish armies had to follow in forced marches the imperial Bavarian armies, which had already been withdrawn to Württemberg, and reached Württemberg exhausted in the rain. There, the Swedish commanders Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar and Gustaf Horn got into a dispute about the strategic question of how to liberate the city of Noerdlingen, which was besieged by the enemy troops. In addition, a Spanish army under the Cardinal Infante had succeeded in penetrating southwestern Germany from the south and uniting with the imperial army before Nördlingen. There, in September 1634, the decisive battle took place, in which the Protestant, Swedish troops under Horn and Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar suffered a devastating defeat, which led to the end of this phase of the war.

After the severe defeat of the Swedes, in the following year 1635, with the exception of the Calvinist-influenced Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, almost all Protestant imperial states led by Electoral Saxony broke away from the alliance with Sweden and concluded the Peace of Prague with Emperor Ferdinand II. In the peace treaty the emperor had to grant the Protestants the suspension of the Edict of Restitution of 1629 for forty years. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian I was also urged to join the alliance and agreed, although he had to incorporate his army of the Catholic League into the new imperial army. The aim of the imperial princes and the imperial army was to act together, with the support of Spain, against France and Sweden as the enemies of the empire. Thus the Thirty Years' War finally ceased to be a war of confessions. In 1635, in response to the Peace of Prague, the Protestant Swedes allied with the Catholic French in the Treaty of Compiègne to also jointly contain the Spanish imperial power of the Habsburgs.

Swedish-French War (1635-1648)

The widely used designation of the last phase of the war as the "Swedish-French War" is slightly misleading. After Emperor Ferdinand III's accession to power in 1637, this phase of the war was essentially characterized by fighting between Imperial Habsburg and Swedish troops. However, this was not the Emperor's intention, as his guiding principle was actually cooperation with Spain and the common fight against France, as the "source of all evil".

Swedish-French War (1635-1648)

Wallerfangen - Dömitz - Haselünne - Wittstock - Rheinfelden Siege - Rheinfelden Battle - Breisach Siege - Wittenweiher - Vlotho - Ochsenfeld - Chemnitz - Bautzen Siege - Freiberg Sieges - Riebelsdorfer Berg - Dorsten - Preßnitz - La Marfée - Wolfenbüttel Siege - Kempener Heide - Schweidnitz - Breitenfeld - Klingenthal - Tuttlingen - Freiburg - Jüterbog - Jankau - Herbsthausen - Alerheim - Korneuburg - Totenhöhe - Hohentübingen - Triebl - Zusmarshausen - Wevelinghoven - Dachau - Prague Siege

French entry into the war

After the heavy defeat in the battle of Nördlingen, the Swedes found themselves in a military crisis situation. Their negotiations with Protestant military leaders and with Electoral Saxony remained without result, as the Swedish needs and demands were not accepted. Instead, in 1635, the Saxon Elector and the Emperor concluded the Peace of Prague, which was subsequently joined by almost all of the Protestant imperial princes and imperial cities that had until then been allied with Sweden. This strengthened the Emperor and Electoral Saxony in the conviction that with the Prague Peace Treaty they had laid the foundation for ending the conflict with Sweden.

This hope proved to be an illusion, for now France, as the previous financial supporter of Sweden, had to fear that the war might end in the Habsburg emperor's favour. France, which until then had only been indirectly involved in the war through a proxy war, decided to now also become active with its own troops. First, a declaration of war was made by France to Spain on May 19, 1635. In March 1635, Spanish troops had taken the city of Trier, which had been occupied by French troops since 1632, in a coup d'état and captured the Elector of Sötern. The release of the allied elector demanded by France was refused, and the elector instead remained in custody until April 1645.

France's declaration of war on the Habsburg Emperor in Vienna took place on 18 September and came only a short time before a planned pre-emptive strike by the Emperor. The declaration of war had only indirect but serious consequences for the Emperor. Hitherto French financial contributions to the Swedes and Spanish contributions to the Emperor had roughly balanced each other out. Now, however, Spain, as an official participant in the war, was itself severely challenged. This was bound to have a negative effect on Spain's financial contributions to the Emperor, while France was not subject to any additional financial demands.

Before France entered the war, the French army had 72 infantry regiments. In the year of the war's entry, the number increased to 135 regiments, reached 174 regiments in 1636, and culminated in a number of 202 regiments in 1647. After an army reform in 1635, each line regiment numbered 1060 men. In 1635 the French infantry numbered about 130,000 men, in 1636 it was about 155,000 men, and in 1647 about 100,000 men. Upon entering the war, the French army was considered to be in poor condition and was composed of soldiers who were inexperienced compared to the Imperial and Swedish soldiers who were battle-hardened in war.

Stabilization of Sweden

In the interaction of France and Sweden, operational demarcations were made in the theatre of war of the Holy Roman Empire. France took over the operational zone of southern Germany, which had been abandoned by Sweden. This included the takeover of fortified towns and redoubts on the Upper Rhine from the Swedes. The Swedes withdrew completely to northern Germany to the coast of the Baltic Sea, Mecklenburg and the Elbe region. There the supplies coming from Sweden by ship across the Baltic Sea were secured. From there Saxony and Bohemia could be threatened, because Brandenburg was a militarily weak opponent.

Since Sweden henceforth no longer supported Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, the latter entered into alliance negotiations of his own with Richelieu. In October 1635, a treaty of alliance and cooperation was concluded. The former Swedish southern army under the commander Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar was placed under the French high command, and the commander was promised territory in Alsace. Bernhard of Weimar was assured four million French pounds annually as a disposal budget to pay officers and men and to pay for equipment, quarters, horses, ammunition and rations. The Southern Army had a strength of 18,000 men, composed of former mercenaries of the Swedish army (so-called St. Bernards or Weimaraners) and French mercenaries. The political leadership under Axel Oxenstierna withdrew to Magdeburg from June 6 to September 19, 1635, and the military commander-in-chief Johan Banér also moved the last Swedish army on German soil to Magdeburg. The treaty basis for this was the Treaty of Wismar, concluded in March 1636 on the basis of the Treaty of Compiègne. According to this treaty, Sweden was to transfer the war via Brandenburg and Saxony to the Habsburg hereditary lands in Bohemia and Moravia, and France was to seize the territories of the Austrian Habsburgs on the Rhine.

When French troops attempted to conquer the Spanish Netherlands in May 1635 and the southern Rhineland in September 1635, the plan failed in the Netherlands with the relief of Louvain by the Imperial Auxiliary Corps for the Spanish under Octavio Piccolomini and on the Rhine by the main Imperial army under Matthias Gallas. Gallas was able to push the allied armies of France and of Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar to Metz, but the latter was able to hold the positions on the Upper Rhine. After the dissolution of the Heilbronn League, the Saxon army formally opened war against its erstwhile ally Sweden in October 1635, blockading Magdeburg from November 1635. The Swedish soldiers became restless and generals also suspected peace negotiations over their heads. After the heavy defeat of the Swedes at Nördlingen a mutiny had threatened in the Swedish army and still in August 1635 the Swedish Chancellor Oxenstierna was held by mutinous groups. He secretly eluded the grasp of the troops in September, fearing for his life. In October 1635, successes by the Swedes under Banér at the battle of Dömitz and then at Kyritz against a Brandenburg army ended the threat of a Swedish collapse.

The Swedes now did everything they could to expand their power base, which had shrunk to Pomerania and Mecklenburg. This was possible because the imperial forces initially concentrated on France and left the expulsion of the Swedes from the imperial territory to Electoral Saxony. Imperial and Bavarian troops under Piccolomini and Johann von Werth supported the Spanish troops in the southern Netherlands in 1636. Together they invaded northern France from Mons in early July. After capturing La Capelle and advancing along the Oise toward Paris, they turned west in the expected direction of the French army, captured Le Catelet, and crossed the Somme from the north in early August. Riots broke out in Paris after the attackers captured the French border fortress of Corbie, only 100 km to the north, in mid-August. With the cooperation of Richelieu and King Louis XIII, a popular army was formed and succeeded in averting the threat to Paris.

In the south, Gallas was to advance into France with another army, for which he gathered his troops in northern Alsace. First, however, he had to send cavalry units into the Spanish Franche-Comté, whose capital Dole was besieged by a French army. The relief succeeded and imperial Lorraine horsemen subsequently devastated the area as far as Dijon. The only possible direction of attack for Gallas' army was Burgundy, since his cavalry was already in place. An advance from there towards Paris, however, was blocked by the army of Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar at Langres. In the north, Corbie was recaptured after a siege by the French popular army in November 1636. The Spanish under the Cardinal Infante had decided too late to declare a relief, considering their operations already completed. The Spanish military leadership ultimately settled for the acquisition of a few French frontier forts, which Piccolomini considered a lost opportunity. At the same time, the Swedes achieved a victory against an Imperial Electorate Saxon army at the Battle of Wittstock. This turned out to be so comprehensive that the imperial troops were needed as reinforcements in the northeast of the empire the next year. Before that, Gallas attempted a final offensive into the interior of France to gain winter quarters in enemy territory and devastate weaker defended areas, but he failed in early November due to bad weather and the fierce defense of the border town of Saint-Jean-de-Losne. Since Franche-Comté did not grant the imperial troops winter quarters, Gallas was forced to withdraw his troops back the long way to the Rhine, against the intentions of the imperial military leadership. Only just under half of Gallas' army eventually remained there to secure the Free County, while the rest were worn out by a long retreat.

After the victory at Wittstock, the situation for Sweden had improved considerably. Electoral Brandenburg was again under Swedish control and the Brandenburg Elector had to flee to Königsberg in Prussia. In the spring of 1637 the Swedes under Banér also invaded Electoral Saxony. The siege of Leipzig failed, however, and after Saxon troops and the main imperial army returning from Burgundy had forced Banér to retreat to Pomerania, the Swedes were again trapped in their coastal base. The war was now treading water again, and the number of operations diminished. The degree of devastation, however, had greatly increased, for whole regions were already deserted.

The Crisis and the Intermediate High of the Habsburgs

The direct war intervention of the French and their subsidy payments had led to the Swedish period of weakness being overcome after 1634. In 1637 the emperor had died. His successor, Ferdinand III, pressed for a settlement, but the Peace of Prague was already history by then. All other peace initiatives, such as those of Pope Urban VIII. (Cologne Peace Congress) or the Hamburg Congress of 1638 had failed. France itself did not want to conclude a peace before the restitution of the Palatinate, Hesse-Kassel, Brunswick-Lüneburg and other Protestant imperial states as well as the receipt of war reparations. Ultimately, Ferdinand III also represented the interests of the old church relations, but made more of an effort to achieve a consensus among the imperial estates.

Direct participation in the war had hitherto met with little success for the French themselves, who had just managed to avert disaster in the Année de Corbie in 1636 and had lost their bridgeheads on the Rhine (Philippsburg and Ehrenbreitstein), once ceded by the Elector of Trier, to the imperial forces by 1637. Only the relief in the fight against the Spaniards by Dutch successes such as the conquest of Breda in 1637 and the advances of Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar on the Upper Rhine successfully brought France back into the action of the war. Bernhard's army first defeated the Duke of Lorraine in northern Franche-Comté in 1637 and then moved to the Upper Rhine. After still being pushed back across the Rhine by Johann von Werth in late 1637, his army inflicted several defeats on the imperial forces over the next year. In January 1638 the Weimar army opened a winter campaign on the left bank of the Rhine and captured the forest towns of Säckingen and Laufenburg. The army then laid siege to the strategically important town of Rheinfelden and, after a first failure on 28 February, defeated in a second attempt on 3 March the imperial relief army under Savelli and Werth, which was completely surprised by its return, in the Battle of Rheinfelden. After taking the city of Freiburg in April 1638, the Weimar army began the siege of Breisach in May 1638. The strongly defended imperial fortress of Breisach had to capitulate in December 1638 despite two attempts to relieve it by imperial Bavarian armies. A campaign planned for 1639 did not take place, as Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar died unexpectedly on 18 July 1639.

In the spring of 1638, Richelieu feared an increasing desire for a separate peace on the part of the Swedish Chancellor of the Realm, Axel Oxenstierna, and therefore urged the adoption of the Treaty of Hamburg. In it, Sweden and France extended their alliance against the emperor and ruled out a respective separate peace with him. Another 14,000 Swedish soldiers reached northern Germany. Banér, who had hitherto been trapped in Pomerania, was able to resume the offensive, while the imperial forces suffered from increasingly poor supplies in the North German war zone. They received insufficient support against the Swedes from the weak Brandenburg army, and their own reinforcements were diverted to the relief of Breisach. When, in addition, a Palatine army financed with English money invaded Westphalia, the commander-in-chief Gallas had to withdraw his own troops from Pomerania to repel it. The imperial forces under Melchior von Hatzfeldt crushed the Palatine-Swedish army under Hereditary Prince Karl Ludwig in the Battle of Vlotho in October 1638. In the northeast, on the other hand, the encirclement of the Swedes in Pomerania finally failed, as it was no longer possible to supply and overwinter the imperial forces in the area. Gallas withdrew his weakened army to the hereditary lands in the winter of 1638, while the Swedes under Johan Banér moved across the depleted territory to Saxony. They defeated a Saxon army at Chemnitz in April 1639 and advanced further into Bohemia to the walls of Prague. The enemies of Habsburg in the empire registered attentively how the superiority of the imperial military was melting away. Amalie Elisabeth of Hesse-Kassel broke off negotiations on joining the Peace of Prague and concluded an alliance with France in the late summer of 1639. The Guelph dukes of Wolfenbüttel and Lüneburg, who were included in the Peace of Prague, entered into an alliance with Sweden.

In 1640, the Emperor convened the Diet of Regensburg, thus setting a trend-setting signal on the long road to peace. The Diet gave the opposition of the estates back their forum. The dominance of the monarchical system had been shattered. Since a peace agreement was not possible without the involvement of France and Sweden, neither the imperial estates nor the emperor could determine an imperial peace. Militarily, the Swedish successes led to the recall of Gallas as commander-in-chief and to the recall of Piccolomini's auxiliary corps for the Spanish to the Austrian hereditary lands. With a well-organized winter campaign, Piccolomini succeeded in driving the Swedes out of Bohemia in early 1640. In spring and summer, the imperial troops and the Swedes faced each other several times without any results, but the imperial troops succeeded in slowly pushing back their opponents. After the conquest of Höxter in early October, the imperial commander-in-chief, Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, surprisingly broke off his own campaign early. At the end of 1640 Swedish troops operated together with the now French former army of Bernard, called the Weimarans; together they advanced as far as Regensburg in January 1641 in one of the typical Swedish lightning campaigns. However, the Allies were unable to blow up the Reichstag, which was meeting there, because the ice on the frozen Danube broke in time and Bavarian cavalry arrived to protect the city.

After Banér's surprise attack he had to flee from superior imperial and Bavarian troops under Piccolomini and Geleen and could only save his army with heavy losses to Saxony, where he arrived deathly ill in Halberstadt. Banér's early death led to signs of disintegration in the Swedish army. This seemed to open a final window for the Swedes' permanent exit from the war. In the summer of 1641, the war between Brandenburg and the Swedes ended, dealing another serious blow to the Prague peace system. Although the emperor now had to give less consideration to Brandenburg's claims to Pomerania in negotiations with the Swedes, the Swedes were granted rights of passage in Brandenburg, which, on the other hand, were not always granted to the imperial forces as a matter of course. The main army of the imperial forces, which continued to operate together with the Bavarians, advanced at the same time through Halberstadt to Wolfenbüttel in order to seize the fortress, which was besieged by Lüneburg troops and the remaining army of the Swedes. An attack on the besiegers' positions failed, but they finally withdrew from the fortress without success. At the same time Hatzfeldt succeeded in capturing Dorsten, the main Hessian fortress in Westphalia. After successes against the German allies of the Swedes, however, the imperial forces did not succeed in crushing the Swedish army, which was successfully reorganized by its new commander-in-chief, Lennart Torstensson, from the end of 1641 and would launch a momentous counterattack in the coming year.

First, the imperial auxiliaries for the Spanish under Lamboy lost the battle at Kempen on the Lower Rhine against Hesse-Kassel and the Weimarans in early 1642. The Bavarian army therefore separated from the imperials to support Electorate-Cologne against the Hessians and French. Torstensson then moved with the Swedish army across Silesia to Moravia, capturing Glogau and Olmütz on the way. Imperial troops maneuvered against the Swedish army and eventually pushed them back into Saxony. The Swedes under Torstensson then laid siege to Leipzig, and the Imperials engaged him at the Second Battle of Breitenfeld. It ended in almost as bad a debacle for the Austrians as the famous First Battle of Breitenfeld.

Fighting in the west, Torstensson war, start of peace negotiations

From 1643, the warring parties - the Empire, France and Sweden - negotiated a possible peace in Münster and Osnabrück. However, the negotiations, always accompanied by further fighting to gain advantages, continued for another five years.

Spain's worsening crisis following the uprisings on the Iberian Peninsula in 1640 and the lost battle at Rocroi against France in 1643 also affected the situation in the empire. Madrid no longer saw itself in a position to support the Viennese Hofburg financially and was militarily tied up to a large extent on the Iberian Peninsula. Henceforth, Vienna could no longer count on Spanish bailouts if it found itself in a military emergency in the Empire. After the death of Bernhard von Weimar, the French failed to make any further progress on the right bank of the Rhine. Only the enormous losses of the Spanish Flanders Army at Rocroi allowed France to operate with larger contingents on the Rhine front. Here, however, Bavaria stood in their way. The Bavarian army was able to hold its own against the French army in southern Germany. It had better supplies than the imperial army and, with Franz von Mercy from Lorraine and the cavalry general Johann von Werth, very capable army commanders. Together with Lorraine and Spanish troops and an imperial corps under Melchior von Hatzfeldt, they succeeded in almost completely annihilating a Franco-Weimaran army at the battle of Tuttlingen. France, meanwhile, was also showing signs of war weariness. There, unrest arose due to the increased tax burden caused by the war. The Bavarian Imperial army succeeded in recapturing Freiburg in 1644 and inflicted heavy losses on the French under General Turenne at the Battle of Lorettoberg. In return, Condé occupied several cities on the Rhine, including Speyer, Philippsburg, Worms and Mainz.

The Swedish military surprisingly withdrew at the end of 1643 after a renewed invasion of Moravia to attack Denmark in the Torstensson War. The imperials responded with an offensive of their own to support the Danes as far as Jutland, but it was unsuccessful. The imperial march back from Holstein turned into a disaster. Trapped in autumn 1644 by Torstensson's Swedish army first in Bernburg, then in Magdeburg, many soldiers deserted. After an outbreak with heavy losses, Gallas' troops made their way to Bohemia. A newly raised army under Hatzfeldt's command confronted the Swedes who had invaded Bohemia at the Battle of Jankau on March 6, 1645, only to be crushed as well. As a result, the remaining imperial troops retreated to Prague to protect the Bohemian capital from further attacks by the Swedes. The Swedes, however, decided to advance further towards Vienna with their army of about 28,000 men. In July 1645, Rákóczi led his troops into Moravia to support Torstensson in the siege of Brno. Ferdinand III recognized the danger of a joint military advance by Torstensson and Rákóczi against Vienna. On 13 December 1645 the Peace of Linz was concluded between Emperor Ferdinand III and Prince George I Rákóczi of Transylvania. However, Saxony, an ally of the Emperor, had previously also concluded the armistice of Kötzschenbroda with the Swedes and had withdrawn from the war. After repelling the Swedish advance on the Danube and successfully defending Brno, the Swedes had to withdraw again from Lower Austria, where they still held Korneuburg until mid-1646, and were also forced back from Bohemia.

In the west, Turenne had invaded Württemberg in the spring of 1645 and was defeated by Mercy's army at Mergentheim-Herbsthausen on 5 May. In August 1645, however, a decisive turn against Bavaria followed with the lost battle of Alerheim, which Mercy and many soldiers lost. The French also suffered heavy losses and were initially forced to retreat back across the Rhine, but in the summer of 1646 a combined allied army of French and Swedes managed to penetrate Bavaria. These took up quarters in Upper Swabia during the winter. Elector Maximilian therefore distanced himself from the Emperor and in March 1647 concluded the Ulm Armistice with France, Sweden and Hesse-Cassel. But only six months later, Bavaria rejoined the imperial forces.

The fighting continued without any major shifts of forces or a decisive battle. Still in May 1648, the last major field battle between the French-Swedish and Imperial-Bavarian armies took place near Augsburg. In a battle of retreat, the imperial Bavarian troops lost their troop and their commander Peter Melander von Holzappel, but were able to retreat to Augsburg in good order. Weakened by casualties and desertions, the allies were subsequently forced to abandon the defensive line on the Lech and retreat to the Inn. This allowed further devastation of Kurbayern. A small Swedish army then entered Bohemia, where in July 1648 it took the Lesser Town of Prague by surprise and then laid siege to the Old and New Towns along with reinforcements that followed. Meanwhile, imperial and Bavarian forces under the command of the recalled Piccolomini slowly pushed the opposing armies out of Bavaria again and won another minor victory at the Battle of Dachau. In southern Bohemia, the imperials were gathering relief troops for besieged Prague. However, a decisive battle for the fate of the city, where the conflict had begun 30 years earlier, was not to take place. At the beginning of November 1648 the Swedes broke off the siege, shortly before the arrival of the imperial relief army, which had already brought news of the Peace of Westphalia concluded on 24 October.

Battle of Rocroi in May 1643

,_ur__Theatri_Europæi...__1663_-_Skoklosters_slott_-_99875.tif.jpg)

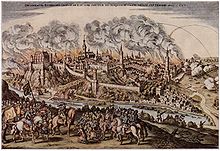

Storming of Prague in October 1648

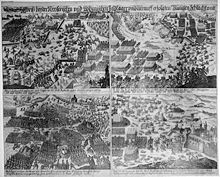

Campaign year 1642, Second Battle of Breitenfeld

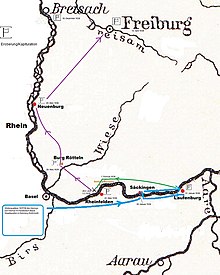

Important battlefields on the southern Upper Rhine 1638

Campaign of Bernhard of Weimar at the beginning of 1638

Battle of Wittstock in October 1636

Battle of Nördlingen in September 1634

Duke Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, German army commander in Swedish-French service

Axel Oxenstierna. Swedish Imperial Chancellor, Commander-in-Chief after the death of Gustav Adolf.

Gustav II Adolf, King of Sweden, mortally wounded in the Battle of Lützen.

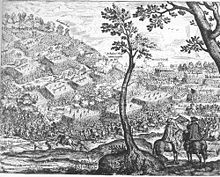

Contemporary depiction of the Battle of Lutter

Albrecht von Wallenstein

Duke Christian of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (painting by Paulus Moreelse, 1619)

Siege of Bautzen in September 1620

Battle of the White Mountain

Martinitz, Slavata and Fabricius were thrown out of one of these windows

Representation of the Second Defenestration of Prague from the Theatrum Europaeum

Questions and Answers

Q: What countries were involved in the Thirty Years' War?

A: The Thirty Years' War was primarily centered in Germany, but several other countries became involved, including France, Spain, and Sweden. In fact, almost all of the powerful countries in Europe were involved in the war.

Q: What caused the Thirty Years' War?

A: The Thirty Years' War began as a fight about religion between Protestants and Catholics. As it continued, Catholic Habsburg dynasty and other countries used it to try to gain more power.

Q: How did France become involved in the war?

A: Catholic France fought for the Protestants during the war which made tensions between them and the Habsburg dynasty even worse.

Q: What effects did this conflict have on Europe?

A: The Thirty Years' War caused things like famine and disease in almost every country that was involved. These problems persisted long after the war had ended.

Q: How long did this conflict last?

A: The Thirty Years' War lasted for 30 years from 1618 until 1648.

Q: How was this conflict resolved?

A: This conflict was resolved with the Treaty of Westphalia at its conclusion in 1648.

Q: What were some of the issues that remained unresolved after this conflict ended?

A: Even though this conflict ended with a treaty, many of its underlying causes remained unresolved for a long time afterwards.

Search within the encyclopedia