Theory of forms

![]()

This article is about Plato's theory of ideas. For other idealistic theories, see Idealism.

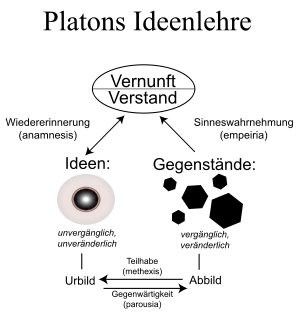

Ideology is the modern term for the philosophical conception, dating back to Plato (428/427-348/347 BC), according to which ideas exist as independent entities and are ontologically superior to the realm of sensually perceptible objects. Such ideas are called "Platonic ideas" to distinguish them from modern usage, in which "ideas" are understood to mean ideas, thoughts, or models. Theories of other philosophers are also referred to by the term "doctrine of ideas," but reference to Plato and Platonism is by far the most common use of the term.

Platonic ideas are, for example, "the beautiful in itself", "the just in itself", "the circle in itself" or "man in himself". According to the doctrine of ideas, ideas are not mere conceptions in the human mind, but an objective metaphysical reality. The Ideas, not the objects of sense experience, constitute the actual reality. They are perfect and unchanging. As archetypes - authoritative patterns - of the individual transient sense objects, they are the precondition of their existence. Plato's conception of ideas thus stands in polar opposition to the view that individual things constitute the whole of reality and that behind the general concepts there is nothing but the need to construct categories of order in order to classify phenomena.

Since the doctrine of ideas is not systematically developed in Plato's works and is also nowhere explicitly described as a doctrine, it is disputed in research whether it is a unified theory at all. An overall picture can only be derived from the numerous scattered statements in Plato's dialogues. In addition, communications of other authors are consulted, but their reliability is disputed. In addition, the conception of ideas does not play a role in some dialogues, is at best present only in hints, or is even criticized, which has led to the assumption that Plato only advocated it temporarily. He only explicitly addressed the ideas in the middle phase of his creative work, but the conception seems to be unspoken in the background even in early dialogues. In the intensively conducted research debates, the position of the "Unitarians", who believe that Plato held a coherent view throughout, is opposed to the "developmental hypothesis" of the "revisionists". The "revisionists" distinguish between different phases of development and assume that Plato abandoned the conception of ideas in his last creative period or at least saw a serious need for revision.

Overview of the doctrine of ideas

Terminology

Plato did not introduce any fixed terminology in his statements on the conception of ideas, but resorted to various expressions of everyday language. For the later so-called "Platonic ideas" he mainly used the words idéa and eídos, but also morphḗ (shape), parádeigma (pattern), génos (gender, here: genus), lógos (here: being), eikōn (image), phýsis (nature) and ousía (being, essence, "beingness"). He often paraphrased the "Platonic idea" of something with expressions like "(the thing in question) itself", "in itself" or "according to its nature".

The most important terms relevant to the reception of the doctrine of ideas are idea and eidos. In common usage, both referred to a visual impression and were usually used synonymously. What was meant was the appearance of something that is seen and thereby makes a certain impression: the appearance, the form or shape, the outward appearance, which is described, for example, as beautiful or ugly. Idea as a verbal abstract is derived from idein "to behold", "to recognize" (aorist to horan "to see").

In contrast to the original literal sense of idea, which refers to the visible appearance of something, the Platonic idea is something invisible that underlies visible appearances. It is, however, mentally apprehensible and thus for Plato "visible" in a figurative sense. Hence he transferred the concept idea from the realm of sense perception to that of a purely spiritual perception. The spiritual "seeing", the "seeing" of ideas plays a central role in Platonism.

A starting point for this shift in meaning from the visual impression made by a concrete individual thing to something general that can only be grasped mentally was already provided by the use of terms in general language usage, which included the general and abstract: Not only single individuals, but also groups and quantities had a certain eidos by which they were distinguished. Thus there was a royal and a slave eidos and an eidos of ethnic groups. Also essential was the fact that the words eidos and idea denoted not only a species-specific appearance, but also, in a derivative sense, its "typical" bearers, characterized by the appearance. What was then meant was the totality of the elements of a set: a species or type, a class of persons, things or phenomena constituted by certain - not only visual - characteristics. In this sense, physicians called a type of patient eidos. A further step of abstraction, already accomplished in common usage, was the use of eidos also for unapparent conditions, for example, different ways of doing things, ways of life, forms of government, or types of wickedness or war. The classification of character traits, attitudes, and behaviors on the basis of the respective eidos - a species-specific quality constituting the species - became seminal for Plato's philosophical use of terms: he asked, for example, about the "idea" of a virtue as what constitutes that virtue. Thus eidos and idea became the philosophical terms for what makes something what it is.

Plato's pupil Aristotle, who rejected the doctrine of ideas, took up his teacher's terminology, but modified it for his own purposes. He used the term idea mostly to designate the "Platonic ideas", whose existence he denied, and usually used eidos to designate the "form" of a sensually perceptible single thing, which as the cause of form gives shape to matter. However, he did not carry out this terminological distinction consistently.

Cicero, an important mediator of Platonic thought to the Latin-speaking world, contributed to the fact that idea also became a philosophical technical term in Latin. He wrote the word still as a foreign word in Greek script; in later authors it appears mostly in Latin script. Other Latin translations of the philosophical terms eidos and idea were forma ("form"), figura ("shape"), exemplar ("pattern"), exemplum ("sample", "model"), and species ("shape", "pattern", "kind"). Seneca spoke of "Platonic ideas" (ideae Platonicae). The late antique translator and commentator of Plato's dialogue Timaeus, Calcidius, also used expressions such as archetypus, archetypum exemplar or species archetypa ("archetypal pattern").

The church father Augustine saw Plato as the originator of the term "ideas", but thought that the content of the term must have been known long before Plato's time. This was to be rendered in Latin with forma or species; the translation ratio was also acceptable, even if not exact, since ratio actually corresponded to the Greek word logos.

Medieval philosophers and theologians adopted the ancient Latin terminology of the doctrine of ideas, which Augustine, Calcidius, and Boethius in particular conveyed to them. To designate the Platonic ideas, they used not only the Latinized Greek word idea but also the purely Latin expressions already in use in antiquity, especially forma.

In the modern German-language research literature, when speaking of Plato's conception, the term "ideas" is predominantly used; in the English-language, "forms" is predominantly used, but also "ideas". Some German-language authors speak of "forms", strongly following the Anglo-Saxon tradition. This translation, however, has the disadvantage of being based on a linguistic regime that starts from the Aristotelian way of thinking.

Starting points for the emergence of the doctrine of ideas

Eleatic and Heraclitean thinking

A starting point for the emergence of the doctrine of ideas was Plato's confrontation with two opposing directions of pre-Socratic philosophy: the way of thinking of the Eleatics and that of Heraclitus and the Heraclites. In Heraclitus' worldview, being and becoming are intertwined and interdependent as two aspects of a unified, comprehensive world order. Reality is not static, but processual, but subject to an eternal lawfulness and insofar also constant. The Eleatic school, which drew on the philosopher Parmenides, esteemed by Plato, interpreted being and becoming in a radically different way. The Eleatics denied the world of becoming and passing away the character of reality and declared all sensory perceptions to be illusory. They contrasted this realm of illusory reality with a world of unchanging being as the only reality. Since sense perception was illusory, it could neither establish knowledge nor refute results obtained by purely mental means. Knowledge could only refer to the unchanging being. Plato took up core elements of this doctrine: both the concept of a single unchanging realm of being, closed to the senses but accessible to the human mind, and the fundamental distrust of sense perception. Like Parmenides, he considered only the unchanging - in his terminology, the ideas - to be essential and strongly devalued everything material and transient.

In contrast to Parmenides, who denied any existence to the changeable as non-being, Plato, however, conceded a conditional and imperfect being to the realm of changeable sense objects. His concept of a hierarchically graded being connected the realm of ideas as the cause with the sense objects as the caused. Thus, like Heraclitus, though in a different way, he established a connection between being and becoming. Such a connection had been declared impossible by Parmenides.

The philosophical defining

A further impetus was given by the philosophical questioning of definitions, which already played a central role for Plato's teacher Socrates (the "what-is? questions"). Perhaps already with Socrates, at the latest in Plato's early creative phase, the view emerged that a definition not only serves as a terminological convention for the purpose of linguistic understanding, but is objectively right or wrong, depending on whether it correctly reflects the essence (the nature) of what is being referred to. Defining should thus directly serve the acquisition of knowledge. Whoever had determined the correct definition had grasped the essence of the thing designated - for example, of a certain virtue - and could then put this knowledge into practice in his life. The objects philosophers were concerned with were exclusively abstract entities such as beauty, "goodness," justice, or bravery. It was assumed that there could be philosophical knowledge only of the general, not of the individual. The idea that the epistemological primacy of the general was matched by an ontological one was obvious. This could lead to the assumption that the actual reality consists in the essence of the general objects under consideration and that these are ontologically independent entities. Such considerations probably paved the way for Plato's view that general objects have a salient existence in a special domain.

The philosophy of mathematics

Plato probably came to the idea that there is both a connection and a sharp, principled contrast between the tangible and the abstract through his study of geometry. He noticed that geometrical thinking is based on the fact that certain forms, such as the shape of a circle, are perceived and investigated sensually and that, as a result, general insights are gained that apply to the "circle in itself". The "circle in itself" as an object of mathematical statements is nowhere sensuously perceptible, but its properties are decisive for the nature of every visible circle. The circles of the sensory world differ in size and in varying degrees of approximation to the ideal circular form, but in respect of what constitutes their circular character they are all alike. As drawn objects, they are necessarily inaccurate images of the imagined ideal circle, that is, of the Platonic idea of the circle. This idea thus proved for Plato to be the pattern and archetype underlying all visible circles. He saw here a relationship between archetype and images, whereby all images owe their existence to the archetype.

The difference in principle between physical and geometrical objects was already known in Plato's time; what was new was the ontological interpretation he gave it. He pointed out that mathematicians presuppose their concepts (such as geometrical figures or types of angles) as known and base their proofs on them as if they knew about them. But they are unable to clarify their concepts and to account to themselves and others for what the things they designate actually are. They rely without justification on alleged evidence, on unquestioned assumptions. It is true that the mathematical subject area is mental and therefore fundamentally accessible to knowledge, but mathematicians have not acquired any real knowledge about it. Such knowledge is not attainable mathematically, but only philosophically: through insight into the ideational character of mathematical objects.

Plato saw the meaning of a study of mathematics in the fact that it clarified the contrast between sensual and nonsensual observation, between perfect archetypes and always defective images, and at the same time directed the view from the visible images to the archetypes that could only be grasped mentally. Therefore, from a didactic point of view, he regarded mathematics as an important preparation for philosophy. What applies to the circle should also apply analogously to ethical and aesthetic matters. Plato saw the value of mathematics for the philosopher only in this propaedeutic function for the doctrine of ideas, not in the results of individual mathematical investigations.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Theory of forms?

A: The Theory of forms is a philosophical idea proposed by Plato, which states that every object in our world has a form that represents its true eternal essence.

Q: How does Plato explain his viewpoint with an example?

A: Plato uses the example of horses to explain his viewpoint. According to him, each horse is an imperfect copy of the horse 'form', which is the one true horse.

Q: Do the Theory of forms apply only to physical objects?

A: No, the Theory of forms applies not only to physical objects but also to abstract concepts such as beauty, anger, good and evil.

Q: Can we perceive the forms through our senses?

A: No, it is impossible for us to perceive the forms through our senses like seeing or hearing.

Q: How can we understand a form?

A: The only way we can truly understand a form is through the use of logic and mathematics.

Q: Can we truly see a form with our eyes?

A: No, even if we try to draw the form on a whiteboard with a ruler, its lines will never be perfectly straight and two-dimensional.

Q: How have we discovered the form of the triangle?

A: We have discovered the form of the triangle through mathematics, a polygon with 3 sides.

Search within the encyclopedia