Republic (Plato)

The Politeia (ancient Greek Πολιτεία "The State"; Latin Res publica) is a work by the Greek philosopher Plato in which justice and its possible realization in an ideal state are discussed. Seven people participate in the fictional, literary dialogue, including Plato's brothers Glaucon and Adeimantos and the orator Thrasymachos. Plato's teacher Socrates is the main character. Others present merely listen.

The Politeia is the first occidental writing that presents an elaborated concept of political philosophy. It is a foundational text of natural law doctrine and is one of the most influential works in the entire history of philosophy. In the 20th century, there has been intense and controversial debate about the extent to which the modern concepts of totalitarianism, communism, and feminism can be applied to positions in the ancient dialogue. Liberal, socialist, and Marxist critics have attacked the concept of the ideal state. Recent scholarship has distanced itself from these ideologically tinged, sometimes polemical debates and assessments. Furthermore, it is disputed whether the Politeia is a purely utopian model or at least to some extent a political programme.

The dialogue, which is divided into ten books, consists of two very different parts. At the beginning (Book 1), Socrates engages in an argument with Thrasymachus about how justice should be defined. In the main section (Books 2-10), Socrates, Glaucon, and Adeimantos struggle to determine the nature of justice and to grasp its value. Socrates suggests that while justice is found in the soul of man, it is more easily seen in the social context, the state. Therefore, he directs the conversation to the question of the conditions under which justice is brought about in the state. In his understanding, a composite whole is just when each part fulfils its natural function. On this basis, Socrates designs the model of an ideal state ordered by estates. Its population is divided into three parts: the class of peasants and artisans, the class of warriors or guards, and the class of "philosopher-rulers" who emerge as a small elite from the guardian class and rule the state. Among the core elements of the concept are two provisions that apply only to the guardians and the rulers: the abolition of private property and the abolition of the family, which is eliminated as an elementary social unit. The traditional tasks of the family, in particular the entire upbringing of children, are taken over by the community of the guardian state. Another striking feature is censorship: poetry that may have an unfavorable effect on the formation of character is not permitted.

In analogy to the three-part structure of the ideal state, Plato's dialogue figure Socrates describes the structure of the soul, which is also composed of three parts. In this model, the diversity of human types and the forms of state that fit them are attributed to different power relationships between the parts of the soul. According to this understanding, the soul is immortal and can access the world of ideas, a metaphysical realm in which the eternal, unchanging "Platonic ideas" are located. The doctrine of ideas that Plato here puts into the mouth of his teacher forms a core component of his own philosophy, not that of the historical Socrates. The idea of the good plays a central role in it. For didactic reasons, this demanding topic is illustrated with three parables: the parable of the sun, the parable of lines, and the parable of the cave.

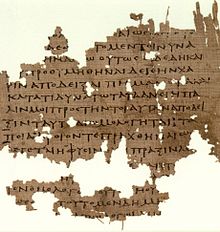

Fragment of the Politeia on a 3rd century papyrus. POxy 3679, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Place and time

The setting of the dialogue is the house of Polemarchus, a rich Metoeco, in the port city of Piraeus, which belongs to Athens. The time of the fictional dialogue plot is unclear and disputed in research, since the chronologically relevant information in the text is contradictory. In any case, the action falls into the time of the Peloponnesian War, which lasted with interruptions from 431 to 404 BC. There is talk of a battle at Megara in which Glaucon and Adeimantos took part. In the context of a historically correct chronology, this can only mean the battle of 409 B.C., for at the time of earlier fighting at the same place, which took place in 424 B.C., Plato's brothers were still children. On the other hand, however, old Cephalus, one of the interlocutors, had been dead for years in 409 BC. This contradiction forms an unresolvable anachronism. But this is not problematic, because Plato also liked to take the liberty of making chronologically inconsistent statements in his literary works. It is possible that the first book of the Politeia, in which Cephalus appears, was originally a separate work with a dramatic date in the 420s; if so, the conversation presented in the rest of the dialogue, with its mention of the Battle of Megara, can be dated around 408/407.

Political and philosophical content

A major topic of research discussion is the question of whether the model of the ideal state was intended as a pure utopia, the realization of which Plato did not seriously consider, or whether he intended to make its implementation appear practicable. Opinions differ widely on this. The text offers evidence for both interpretations. The question of practicability is discussed variously in the dialogue, with different views coming to the fore. The spectrum of modern interpretations ranges from the assumption that Plato wanted to demonstrate impracticability to the hypothesis that he wanted to provide a concrete plot for contemporary constitutional reform. Some interpreters, including Leo Strauss, even believe that it is an "anti-utopia" that Plato neither considered possible nor desirable; his depiction of the utopian state as an ideal should be understood ironically. According to one school of thought, Plato's main concern was not political, but ethical; the model of the state is not to be understood as a political program, but as a symbol of desirable inner-soul conditions.

There is also a lively discussion of the interpretation of Plato's fundamental poetic criticism of Socrates. This makes an ambivalent impression. Socrates points to an "old dispute" that exists between philosophy and poetry. On the one hand, he repeatedly presents his criticism of poetry with great emphasis and gives detailed reasons for it, but on the other hand he puts it into perspective: he confesses that he has felt love and reverence for Homer since his youth, expresses his regret that there is no place for poets in the ideal state, and emphasizes that he would be glad to be convinced if poets or poet friends succeeded in showing that poetry does fulfil a useful function in society.

One topic of modern philosophical debate is the meaning of the "noble lie" recommended by Socrates, the invention of myths and inaccurate claims by philosopher-rulers for the purpose of salutary influence on the minds of the governed. This problematic is embedded in the question of the philosophical understanding of truth and fictionality. At issue is the function of myths in Plato's discourse, the relationship between literal and symbolic truth, and the tension between the "noble lie" and the love of truth that Plato also recommends. Plato accepts and recommends myths and, in the literal sense, inaccurate claims when they are in the service of what he sees as a higher-order truth. Higher-order philosophical truth is good in and of itself and always desirable. Non-philosophical truths, on the other hand, are to be judged according to their respective utility; they are valuable only if they promote virtuous behavior.

Kai Trampedach points to the "anti-politics" of the ideal state, which is in the sharpest contradiction to the Greek concept of the political, since it separates citizen status, service in arms, and authority to rule from each other completely and fundamentally. Not only in the lowest rank, but also among the guards, the actually political had no space, and even among the rulers a space of communicative decision-making was missing. The consensus of the philosopher-rulers, which exists on the basis of knowledge, leaves politics no starting point and makes political institutions superfluous.

Plato's understanding of the role of women in state and society is controversial. One line of research, whose spokesman is Gregory Vlastos, regards him as a "feminist". Other researchers, in particular Julia Annas, strongly disagree with this designation. What is essential here is how one defines the term feminism. In today's common sense of the term, Plato's position is not feminist, but by the standards of the conditions and ways of thinking of the time, he appears to be an advocate of women's emancipation, for he wanted to open access to all offices in the ideal state to women. Considering the status of women at the time, Plato's proposals were revolutionary, for in democratic Athens women could not participate in the popular assembly or hold political office. Moreover, among the upper classes, women's roles were largely limited to performing domestic tasks and they had few educational opportunities. For women guardians in the ideal state, on the other hand, inclusion in public life was foreseen.

The abolition of private property among the guardians and the rulers is often compared to the economics of modern communism. In this context, Plato has been called the "first communist". In more recent research, however, it is emphasized that in the ideal state the lowest estate, which is responsible for the entire production of goods, is organized in private enterprise and, in particular, no collectivization of agriculture is envisaged. Therefore, the term "communism" is inappropriate.

Of central importance is Plato's definition of justice as a principle of order in the soul and consequently also in the state. In this way, his concept of justice differs fundamentally from all approaches that define justice with reference to social behavior. Although for Plato the existence of just order necessarily results in virtuous social action, this does not constitute justice, but is only an effect of it.

It is disputed whether Plato's Socrates, in his defense of justice, commits a fallacy of equivocation by not always using the term "justice" in the same sense in his argumentation, but partly in the sense of the common understanding of the time ("vulgar justice"), partly in the sense of his own ("Platonic justice").

A major innovation in the Politeia is the introduction of the model of the tripartite soul. In earlier works Plato had treated the soul as a unity. The detailed justification of the new model, which is supposed to explain the irrational forces in the soul, is probably due to the novelty of the idea. Difficult to determine is the relationship of the tripartite model to the doctrine of immortality; intensely debated is the question of how Plato reconciled the tripartite nature of the soul with its unity, indestructibility, and incorporeal existence.

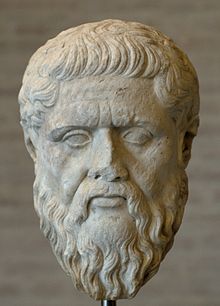

Plato (Roman copy of the Greek portrait of Plato by Silanion, Glyptothek Munich)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is The Republic?

A: The Republic is a book written by Plato.

Q: When was The Republic finished?

A: The Republic was finished in 375 BC.

Q: What questions does The Republic ask?

A: The Republic asks the questions 'why should people do good things?' and 'are people punished for doing bad things?'

Q: What did Plato say about doing bad things?

A: Plato said that people should not do bad things because people who do bad things end up unhappy.

Q: Who did Plato believe should have power in a society?

A: Plato believed that philosophers are best able to do good things and so they should be given power in a society.

Q: Why did Plato think non-philosophers should allow themselves to be ruled by philosophers?

A: Plato believed that non-philosophers should allow themselves to be ruled by philosophers because the rule of peoples (democracy) often falls because of unreasonable confusion.

Q: What is Platonism?

A: Platonism is a philosophy introduced by Plato that explores topics such as metaphysics, psychology, religion, and most branches of philosophy.

Search within the encyclopedia