Teutonic Order

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see German Order (disambiguation).

The Teutonic Order, also known as the Teutonic Order, Teutonic Knights or Teutonic Order, is a Roman Catholic religious order. With the Order of Malta, it stands in the (legal) succession of the knightly orders from the time of the Crusades. The members of the Order have been regular canons since the reform of the Order's rule in 1929. The order has about 1000 members (as of 2018), including 100 priests and 200 religious sisters, who devote themselves mainly to charitable tasks. Today the headquarters are in Vienna.

The full name is Order of the Brothers of the German Hospital of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, Latin Ordo fratrum domus hospitalis Sanctae Mariae Teutonicorum Ierosolimitanorum. From the Latin abbreviation Ordo Theutonicorum or Ordo Teutonicus the abbreviation OT is derived.

The origins of the Order lie in a field hospital of Bremen and Lübeck merchants during the Third Crusade around 1190 in the Holy Land during the siege of the city of Acre. Pope Innocent III confirmed the transformation of the Spitalgemeinschaft into a knightly order on February 19, 1199, and the granting of the Knights of St. John and the Knights Templar to the friars of the German House of St. Mary in Jerusalem. After the elevation of the Spitalgemeinschaft to a clerical order of knights, the members of the originally charitable community became involved in the Holy Roman Empire, the Holy Land, the Mediterranean region as well as in Transylvania during the 13th century and participated in the German colonisation of the East. This led to a number of settlements with more or less long existence. A central role was played from the end of the 13th century by the Teutonic Order state founded in the Baltic. At the end of the 14th century, it covered an area of about 200,000 square kilometres.

Due to the heavy military defeat at Tannenberg in the summer of 1410 against the Polish-Lithuanian Union as well as a protracted conflict with the Prussian estates in the middle of the 15th century, the decline of both the Order and its state system, which began around 1400, accelerated. As a result of the secularisation of the remaining state of the Order in the course of the Reformation in 1525 and its transformation into a secular duchy, the Order no longer exercised any influence worth mentioning in Prussia and after 1561 in Livonia. However, it continued to exist in the Holy Roman Empire with considerable landholdings, especially in southern Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

After the loss of territories on the left bank of the Rhine in the late 18th century as a result of the Coalition Wars and after secularisation in the Rhine Confederation states at the beginning of the 19th century, only the possessions in the Austrian Empire remained. With the disintegration of the Habsburg Danube Monarchy and the Austrian Law on the Abolition of the Nobility after the First World War of April 1919, the knightly component in the structure of the Order was lost in addition to the loss of considerable possessions. Since 1929 the Order has been led by religious priests and is thus run according to canon law in the form of a clerical order.

In the 19th and in the first half of the 20th century, the historiographical reception was mostly concerned only with the presence of the then Order of Knights in the Baltic States - the Teutonic Order state was equated with the Order itself. Research and interpretation of the Order's history were extremely different in Germany, Poland and Russia, strongly national or even nationalistic. A methodical reappraisal of the history and structures of the Order began internationally only after 1945.

History

Foundation and beginnings in the Holy Land and Europe

Previous story

After the First Crusade led to the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, the first chivalric religious orders were established in the four crusader states (known as Outremer in their entirety). Originally, they provided medical and logistical support to Christian pilgrims visiting the biblical sites. To these tasks were soon added the protection and escort of the faithful in the militarily always embattled country. In 1099, the French-dominated Order of St. John was formed, and after 1119 the Order of the Temple, which was more oriented towards military aspects.

As a result of the crushing defeat of the Crusaders in 1187 at the Battle of Hattin, the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was lost to Saladin, the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. As a result, the Third Crusade began in 1189. From remaining bases on the coast, the Crusaders attempted to retake Jerusalem. The first target was the port city of Acre.

pre-Acre foundation

During the siege of Acre (1189-1191), catastrophic hygienic conditions prevailed in the crusaders' camp on the Toron plateau (not to be confused with the later castle of the same name), which was largely blocked by Muslim troops. Crusaders from Bremen and Lübeck who had travelled by sea therefore founded a field hospital there. According to legend, the sail of a cog stretched over the sick was the first hospital of the Germans.

The well-established hospital continued to exist after the conquest of Acre. The brothers serving there adopted the charitable rules of the Knights of St. John and named the institution "St. Mary's Hospital of the Germans in Jerusalem" - in memory of a hospital that is said to have existed in Jerusalem until 1187. In the Holy City, after the expected victory over the Muslims, the main house of the order was also to be built.

The hospital gained economic importance through donations, especially from Henry of Champagne. In addition, the Order was given new military tasks. Emperor Henry VI finally obtained official recognition of the hospital by Pope Clement III on 6 February 1191.

During the German Crusade, the community of the former nurses was raised to the status of a knightly order in March 1198 at the instigation of Wolfger of Erla and Konrad of Querfurt, following the example of the Knights Templar and the Knights of St. John. The recognition as a knightly order was granted by Pope Innocent III on February 19, 1199, and the first Grand Master was Heinrich Walpot von Bassenheim. After the death of Henry VI (1197) and the unsuccessful end of the crusade, which was primarily supported by the German feudal nobility, an order of knights influenced by the German nobility was to serve as a political ally of the future ruler in the empire through family relations and feudal dependencies. Until then, the Staufer and Guelph power groups in Outremer, which were fighting over the vacant imperial throne, had no clerical institution representing their interests. German interests in the national sense, however, were unknown in the Holy Roman Empire.

Membership structures and distribution of the Order of Knights in the High Middle Ages

The members of the Order were bound by the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Voting rights in the General Chapter, on the other hand, were only granted to knights and priests. Like all knightly orders of the Middle Ages, the Teutonic Order initially consisted of:

- Brother Knights: The military power of the order; any man knighted in the early days could advance to knighthood with profession under the assistance of a credible guarantor. From the late 15th century, the dignity of knight was reserved for native-born nobles. Prior to that, nobles, burghers, and predominantly ministerials were encountered. Although the brother knights were often associated with chivalric monks, they were in fact considered laymen. The Institute of the Professed Knights existed until 1929.

- priestly brothers: The priests of the order were responsible for the observance of the liturgy and the performance of sacred acts. Furthermore, in the course of the Middle Ages, the priest-brothers were used as chroniclers or chancery officials of the order's lords due to their scriptural education. Their range of activity was limited to these fields, but the bishops of the order also came from their ranks.

- Sariant Brothers: These were proven non-noble laymen who served as lightly armed fighters, couriers, or subordinate administrators. Sariant brothers existed only until the end of the Middle Ages.

- Serving half-brothers (so-called half-crucifers): This group did subordinate work in court and housekeeping, but also provided guard services. The branch of the serving half-brothers existed until the end of the Middle Ages.

In addition to military tasks, nursing and care of the poor initially remained important focal points of the Order's activities. As a result of donations and inheritances, the knights of the order received considerable landed property and numerous hospitals. The latter were run by priests and half-brothers. The extensive willingness of the feudal nobility to donate can be explained by the world view of the early 13th century, which was characterised by "fear for the salvation of the soul" and a spiritual "mood of the end of time". Through the donations in favour of the order, one tried to assure one's own salvation.

In 1221, through a papal general privilege, the Order succeeded in obtaining its full exemption from the diocesan authority of the bishops. The income was increased by the granting of the right to a comprehensive collection also in parishes not assigned to the Order. In return for appropriate remuneration (legate), persons subject to ban or interdict were also allowed to be buried in "consecrated earth" in the cemeteries of the Order's churches, which would otherwise have been denied them. The Order was ecclesiastically independent of the Pope and thus on an equal footing with the Knights of St John and the Knights Templar. On the part of these communities, the Teutonic Order was viewed with increasing scepticism, not least because of its acquisitions. The Templars claimed the White Mantle for themselves and even lodged an official protest with Pope Innocent III in 1210. It was not until 1220 that Pope Honorius III finally confirmed that the Teutonic Knights could wear the disputed mantle. Meanwhile, the Templars remained bitter rivals of the Teutonic Order. A formal war broke out in Palestine. In 1241, the Templars expelled the Teutonic Lords from almost all their possessions and no longer tolerated even their clergy in the churches.

Already at the end of the 12th century the Order received its first possessions in Europe. In 1197, a hospital of the Order was mentioned for the first time in Barletta in southern Italy. The first settlement on the territory of the Holy Roman Empire north of the Alps was a hospital in Halle around 1200. Brothers of the Order founded St. Kunigunden on a site to the west of the city that had been donated to them. The hospital was named after the canonised Empress Kunigunde, the wife of Henry II. The scattered territorial possessions soon became so extensive that a land commander had to be appointed for Germany as early as 1218. In the following decades, the Order spread throughout the entire territory of the Empire, favoured by numerous foundations and the accession of prominent and wealthy nobles.

In 1228/1229, the Teutonic Order unreservedly supported the crusade of Emperor Frederick II, in which Grand Master Hermann von Salza played a major role. This brought the Order the feudal exemtion. This important privilege did not release the Order from the feudal bond of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, but it did free it from all obligations towards it. This renunciation of all royal rights by the Kingdom of Jerusalem is without precedent. Emperor Frederick II, at the same time King of Jerusalem as a result of his marriage to Isabella of Brienne, wished to integrate the Order in a prominent position in his imperial policy. The comprehensive privilege can be traced back to the work of Hermann of Salza, one of the most important advisors and diplomats of the emperor. Frederick granted the Order a number of other privileges, such as the gold bull of Rimini in 1226.

Contingents of the Order's knights supported the Central European dominions affected by the attack of the Mongol armies under Batu Khan in 1241. In the lost battle of Liegnitz, for example, the entire contingent of the Order deployed to defend Silesia was worn down.

Development in Europe and Palestine until the end of the 13th century

The Order in the Holy Land

In the Holy Land, the Order succeeded not only in acquiring a share of the port customs in Acre, but also, through the donation of Otto von Botenlauben, the former dominion of Joscelin III of Edessa in the environs of the city (1220). In addition, the castle of Montfort (1220), the dominions of Toron (1229) and Schuf (1257) and the castle of Toron in the dominion of Banyas (1261) were acquired.

Nevertheless, the end of the Crusaders' rule in the Holy Land was in sight. Jerusalem, acquired peacefully by Emperor Frederick II in 1229, finally fell in 1244. After the victory of the Egyptian Mamluks over the Mongol armies of the Ilkhanate, which until then had been considered invincible, in the battle of ʿAin Jālūt in 1260, Mamluk forces increasingly put the bastions of the crusaders under pressure. The remaining fortresses of the knightly orders were systematically conquered in the following decades. With the fall of Acre in 1291, the end of the "armed marches to the grave (of Christ)" was finally in sight. A significant contingent of Teutonic Knights took part in the final battle at Acre. It was led by the Grand Master Burchard von Schwanden until his abrupt resignation, then by the War Commander Heinrich von Bouland.

The final loss of Acre in 1291 marked the end of the Teutonic Order's military involvement in the Holy Land. Unlike the multinationally oriented Knights of St. John and the Knights Templar, the presence of the Teutonic Order was then concentrated within the borders of the Empire and in the newly acquired bases in Prussia. However, the headquarters of the Grand Master was still located in Venice, an important port for the passage to the Holy Land, until 1309, due to the temporarily persisting hope for a reconquest of the Holy Land.

Kingdom of Sicily and Levant

In the Kingdom of Sicily and in the Levant, a number of branches of the Order were founded in the first quarter of the 13th century. Especially in the Kingdom of Sicily, a large number of smaller houses of the Order were founded after 1222 as part of the preparations for the Crusade of Frederick II, the most important of which were the already older commandery in Barletta and the houses in Palermo and Brindisi. In Greece, too, on the west coast of the Peloponnese, there were isolated branches, which primarily served to supply pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land and on their way back.

Failed state formation in Transylvania

In view of the fragmented possessions, Grand Master Hermann von Salza seems to have striven early on to establish a coherent territory dominated by the Teutonic Order. Against this background, it is to be understood that he willingly accepted a request for help from the Kingdom of Hungary in 1211, at a time when the available forces of the Order were actually tied up for the purpose of liberating the tomb in Outremer. Andrew II of Hungary offered the Order to acquire a birthright in the Burzenland in Transylvania through war services against the Cumans. The king also conceded important ecclesiastical levies, including the right to tithe, to the Order. Furthermore, he was allowed to mint coins and to fortify his castles with stones. The latter was considered a special privilege of the king in Hungary.

However, Hungary's relations with the Teutonic Order soon began to deteriorate. Anti-German resentment grew in the country, which also led to the death of Gertrud of Andechs in 1213. The queen was the German-born wife of Andreas II. In 1223 Pope Honorius III granted the Order an exemption privilege in the form of a bull, which explicitly referred to Burzenland. Its implementation would have de facto abolished Hungary's last legislative ties to the territory it claimed. The Hungarian nobility therefore massively urged the king to resist the Order.

On the advice of Hermann von Salza, the Pope attempted in 1224 to administratively enforce the privilege documented the previous year. For this purpose, he placed the Burzenland under the protection of the Apostolic See without further ado. This was intended to provide legal support for the Teutonic Order, which was directly subordinate to the Pope, in its land seizure and in the flare-up of hostilities with the Hungarians. Andrew II now intervened militarily. The numerically highly superior Hungarian army besieged and conquered the few castles of the Order.

The attempt of the Teutonic Order to establish an autonomous dominion outside the Hungarian kingdom by invoking the granted homeland right and with the active support of the Pope ended in 1225 with the expulsion of the Order and the destruction of its castles.

The possessions north of the Alps

One of the most important charitable institutions taken over by the Order was the hospital founded by the Landgravine Elisabeth of Thuringia in Marburg. It was continued and expanded by the Order after her death in 1231. With the canonisation of Elisabeth in 1235, this hospital and its operators acquired a special spiritual significance. The resulting reputation for the order increased even more when the saint was reburied in the spring of 1236 with the personal participation of Emperor Frederick II.

In the first half of the 13th century, the individual commends were combined into regionally structured bailiwicks. Thus, the bailiwick of Saxony was created around 1214, the bailiwick of Thuringia before 1221, the bailiwick of Bohemia and Moravia in 1222, the bailiwick of the Teutonic Order Alden Biesen before 1228, and the bailiwick of Marburg in 1237. Later followed Lorraine (1246), Coblenz (1256), Franconia (1268), Westphalia (1287). Like the bailiwicks of Austria and Swabia-Alsace-Burgundy, these possessions were subject to the Deutschmeister. In northern Germany, too, there were isolated commends near the Baltic ports of Lübeck and Wismar, which were directly subordinate to the Landmeister in Livonia. These served primarily for the logistic handling of armed pilgrimages to the Baltic States. There, the Order developed its own state system.

The State of the Teutonic Order

→ Main article: Teutonic Order state and Teutonic Order castle

Concentration on the Baltic States and Eastern Colonization

The history of the Order between 1230 and 1525 is closely linked to the fate of the Teutonic Order, which later became the Duchy of Prussia, Latvia and Estonia.

A second attempt at land acquisition was successful in a region that offered a far-reaching perspective to the Order of Knights' missionary command, the Baltic States. Already in 1224, Emperor Frederick II had placed the pagan inhabitants of the Prussian land east of the Vistula and the neighbouring areas under the direct control of the Church and the Empire as imperial freemen. As papal legate for Livonia and Prussia, William of Modena confirmed this step in the same year.

In 1226, the Polish duke of the Piasts, Conrad I of Masovia, called upon the Teutonic Order to help him in his fight against the Pruzes for the Kulmerland. After the unfortunate experiences with Hungary, the Teutonic Order secured itself legally this time. It got a guarantee from Emperor Frederick II with the Golden Bull of Rimini and from Pope Gregory IX with the Bull of Rieti that after the subjugation and missionization of the Baltic, i.e. the Pruzes, the conquered land should fall to the Order. At his insistence, the Order also received the assurance that, as sovereign of this territory, it would be subject only to the Pope, but not to any secular feudal lord. After a longer hesitation, Conrad I of Masovia ceded the Kulmerland to the Order in 1230 in the Treaty of Kruschwitz "in perpetuity". The Teutonic Order regarded this treaty as an instrument for the creation of an independent dominion in Prussia. Its wording and authenticity have been questioned by some historians.

In 1231, Landmeister Hermann von Balk crossed the Vistula with seven knights of the Order and about 700 men. He built a first castle, Thorn, in Kulmerland in the same year. From here the Teutonic Order began the gradual conquest of the territory north of the Vistula. The conquest was accompanied by purposeful settlement, whereby the settlements founded by the Order were mostly granted the right documented in the Kulmer Handfeste. In the first years the Order was supported by troops of Conrad of Masovia as well as the other Polish constituent princes and by crusader armies from the Empire and many countries of Western Europe. Pope Gregory IX granted the participants in the war campaign against the Pruzes the extensive forgiveness of sins and other promises of salvation that were customary for a crusade to the Holy Land.

The remaining knights of the Order of the Brothers of Dobrin (fratribus militiae Christi in Prussia) were incorporated into the Teutonic Order in 1234. The Order had been founded in 1228 on the initiative of Conrad to protect the Masovian heartland, but could not prevail militarily against the Prussians.

Founded in Riga in 1202, the Order of the Brothers of the Sword (regalia: white cloak with red cross) suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Schaulen in 1236 against Shamaite Lithuanians and Semigallers. Thereupon Hermann of Salza personally negotiated the Union of Viterbo with the Curia, as a result of which the Teutonic Order and the Order of the Brothers of the Sword were united. Thus, together with the Livonian commends, a second heartland was acquired, the so-called Mastery of Livonia, where, following the example of Prussia, the already existing system of castles (so-called fortified houses) was expanded.

The sustained eastward expansion of the Livonian Union ended at the Narva River. After Pskov was temporarily occupied in 1240, there were constant battles between knights of the Livonian branch of the Order as well as retainers of the Livonian bishops and Russian detachments. These culminated in April 1242 in the Battle of Lake Peipus (also known as the Battle of Ice), the exact course and extent of which is disputed among historians. A Russian contingent under Alexander Nevsky, Prince of Novgorod, defeated a larger army division under Hermann I of Buxthoeven, Bishop of Dorpat. In the summer of 1242 a peace treaty was concluded. It de facto fixed the respective spheres of influence for more than 150 years.

The subjugation of the settlement area of the Prussians was accompanied by Christianization and German settlement of the land. This undertaking occupied the Order for more than 50 years and was only completed in 1285 after severe setbacks, such as various revolts by the Pruzes. The original legitimizing objective of the so-called heathen mission was retained even after the missionization of Prussia.

Structural and economic rationality

The Order created for itself a dominion whose organizational structures and modernity in economic thinking in the Empire were equaled at best by Nuremberg and which in many respects were reminiscent of the most advanced state systems in Upper Italy. He was already a significant economic factor in his nominal capacity as sovereign and, moreover, drew greater profit from the land through his efficient structures governed by economic planning and rationality. He became the only non-urban member of the Hanseatic League and maintained a branch in Lübeck with the court of the Teutonic Order. As a resource-rich riparian of the Baltic economic area, which flourished through the Hanseatic League of Cities, this opened up new trading opportunities and expanded scope for action.

In economic and administrative terms, the Order State was one of the most modern and prosperous polities when compared to the territorial states of the Greater Region. Far-reaching innovations in agriculture as well as pragmatic innovations in the field of craft production in connection with efficient administration and a highly developed monetary economy characterize an organizational structure superior to the traditional feudal system. The expansion of the transport infrastructure, which was accelerated after 1282, and the perfection of the communications system had a beneficial effect.

Lithuanian wars and heyday (1303 to 1410)

The Grand Master had his headquarters in Acre until 1291, when this last crusader base was lost. Konrad von Feuchtwangen therefore resided in Venice, traditionally an important port for embarkation to Outremer. In 1309 Grand Master Siegfried von Feuchtwangen moved his seat to Marienburg on the Nogat. Prussia had thus become the centre of the Order. During this period, the Knights Templar were persecuted by King Philip IV of France, who was supported by the compliant Pope Clement V. The orders of chivalry were the focus of general criticism in the first decade of the 14th century due to the loss of the Holy Land. Thus, it seemed advisable to move the seat of the Grand Master to the center of their own territorial power base.

The seizure of Danzig and Pomerelia in 1308 took place through military action against Polish duchies and on the basis of the Treaty of Soldin with the Margraviate of Brandenburg. In Poland, not least because of these events, resentment grew against the Order and also against Germans residing in Poland. In 1312 the uprising of the bailiff Albert was put down in Krakow and the Germans were expelled. In the following years, Władysław I Ellenlang was able to consolidate the territorially fragmented Poland of the Piast period as the Kingdom of Poland. Archbishop Jakub Świnka of Gniezno in particular advocated a policy of separation from the Germans. The conflicts between the Order and local Polish rulers, which arose as a result of the loss of Pomerania and Danzig, as well as a kingdom that was politically weak for the time being, subsequently developed into a permanent feud. Even the peace treaty of Kalisz, in which Poland officially renounced Pomerelia and Gdansk in 1343, did not bring any long-term relief between the Order and Poland.

With Lithuania in the southeast, moreover, a Grand Duchy gradually rose against which the Order was engaged in constant warfare for ideological and territorial reasons. The Lithuanian Wars of the Teutonic Order lasted for more than a century, from 1303 to 1410. Since this eastern grand principality vehemently rejected baptism, the Lithuanians were officially considered pagans. The constant emphasis on the mission of the pagans only inadequately concealed the territorial interests of the Order, especially in Schamaiten (Lower Lithuania). By continuous support of noble Prussian riders the war was carried to Lithuania by many smaller campaigns. The Grand Princes of Lithuania, for their part, proceeded in the same way and repeatedly advanced into Prussian and Livonian territory. A climax of the wars was the Battle of Rudau in 1370. North of Königsberg, an army of the Order under the command of Grand Master Winrich of Kniprode and the Order's Marshal defeated a Lithuanian force. Notwithstanding this, Lithuania, which extended far to the east, could never be permanently conquered. The reason for this successful resistance is considered to be the numerical strength of the Lithuanians in comparison with other ethnic groups subjugated by the Order, such as the Prussians, the Boers and the Estonians, as well as their effective political organisation.

Grand Master Winrich von Kniprode led the Order's state and thus the Order to its greatest flowering. A consolidated economy and sustained military successes against Lithuania proved to be the key to success. The number of knight-brothers nevertheless remained small, around 1410 about 1400, around the middle of the 15th century only 780 members of the order belonged to this group. Under Konrad von Jungingen the greatest expansion of the Order was achieved with the conquest of Gotland, the peaceful acquisition of the Neumark and Samaiten. The conquest of Gotland in 1398 aimed at the crushing of the Vitalien brothers encamped there. This meant the liberation from piracy, which had become a plague, within the main Hanseatic routes on the eastern Baltic Sea. As a consequence, the Order occupied Gotland militarily as a bargaining chip. It was not until 1408 that a settlement was reached with the Kingdom of Denmark, which was also interested in possession of the island. Margarethe I. of Denmark paid 9000 Nobel, thus about 63 kilograms of gold. However, the agreement came about under the aspect of the emerging escalation of the conflict with the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

In 1386, the marriage of Grand Duke Jogaila to Queen Hedwig of Poland had united the two main opponents of the Order. At the beginning of August 1409, the Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen sent his opponents the "Feud Letters", declaring war.

On July 15, 1410, a united Polish-Lithuanian force defeated the army of the Order in the Battle of Tannenberg, which was supplemented by Prussian troops, guest knights from many parts of Western Europe and mercenary units. The Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen was also killed, along with almost all of the Order's commanders and many of its knights.

The Order was able to preserve the core of its Prussian territories, including Marienburg, through the efforts of the Commander and later Grand Master Heinrich von Plauen, and to maintain it in the First Peace of Thorn of 1411. With this peace treaty as well as its amendment in the Peace of Melnosee in 1422 the war campaigns of the Order's forces against Lithuania and against the later personal union Poland-Lithuania, which had been carried out offensively for more than a hundred years and had been permanently weakened at Tannenberg, came to an end. However, in the Peace of Thorn high contributions in the amount of 100,000 shocks of Bohemian groschen, among other things for the ransom of prisoners, had to be paid. The contributions led to the introduction of a special tax, the so-called Schoss, which contributed to a hitherto unusually high tax burden on the Prussian estates.

Prussia (1410 to 1525)

Already towards the end of the 14th century a destructive development for the Order and its state became apparent. While the European chivalry in the late Middle Ages decayed, the "fight for the cross" was increasingly transfigured and stood for an ideal that hardly lasted in the reality of the time.

The nobility increasingly reduced the knightly orders to a secure supply base for descendants not entitled to inherit. Accordingly, the motivation of the knighthood decreased. Everyday tasks in the administration of the Teutonic Order were now perceived as burdensome duties. The conservative liturgy of the Order contributed to this view. The daily routine in times of peace was meticulously regulated. In contrast, the contents of a spiritual order of knights with missionary character had largely outlived their usefulness. Moreover, at the instigation of the King of Poland at the Council of Constance (1414-1418), the Order was formally prohibited from further missionary activity in the now officially Christian Lithuania.

In the crisis following the heavy defeat of 1410, the grievances widened. Internal disputes weakened both the Order itself and subsequently the Order's state. Landsmannschaftliche groups fought for influence in the Order, the Teutonic Master strove for independence from the Grand Master. The cities of Prussia and the Kulm landed gentry, united in the Lizard League, demanded co-determination due to the strongly increased taxation to pay the war costs and the contributions to be paid to Poland-Lithuania, which, however, were not granted to them. Thus they united in 1440 in the Prussian alliance. Grand Master Ludwig von Erlichshausen intensified the conflict by his demands on the Estates. Emperor Frederick III sided with the Order at the end of 1453. On the occasion of the marriage of King Casimir IV of Poland with Elisabeth of Habsburg, the Prussian League entered into a protective alliance with Poland at the beginning of 1454 and openly rebelled against the Order's rule.

Thereupon the Thirteen Years' War broke out, which was characterized by sieges and raids, but hardly by open field battles. As early as September 1454, Polish troops were defeated at the Battle of Konitz and subsequently provided only marginal support to the Prussian uprising. Eventually, due to general exhaustion, a stalemate was reached. The Order could no longer pay its mercenaries and for this reason even had to abandon its main residence, the Marienburg. The castle was pledged to the unpaid mercenaries, who immediately sold it to the King of Poland. In the end, the higher financial strength of the rebellious cities, which paid all war costs themselves, including Danzig in particular, tipped the scales.

In the Second Peace of Thorn in 1466, the Order now also lost Pomerelia, Kulmerland, Warmia and Marienburg. This treaty was recognized neither by the emperor nor by the pope. But the Order as a whole had to acknowledge the Polish feudal sovereignty, which from then on every newly appointed Grand Master tried to avoid by delaying or even not taking the feudal oath. A large part of the Prussian cities and territories in the west could free themselves from the Order's rule as a result of the Second Treaty of Thorn.

To maintain the territorially shrunken state of the Order, subsidies from the bailiwicks in the Holy Roman Empire were now needed, which put many of the commends there in a difficult financial situation. The Teutonic Master Ulrich von Lentersheim tried to relieve himself of these obligations, and as a result requested support from the Emperor on his own authority, and for this purpose placed himself under the feudal sovereignty of Maximilian I in 1494. This procedure, however, contradicted the treaties of Kujawisch Brest and Thorn with Poland, which resulted in protests from the Prussian branch of the Order and especially from the Kingdom of Poland.

The Grand Master Albrecht I of Brandenburg-Ansbach tried unsuccessfully to gain independence from the Polish Crown in the so-called Equestrian War (1519-1521). In the hope of thereby receiving support from the Holy Roman Empire, he subordinated the Prussian territory of the Order to the fiefdom of the Empire in 1524 and undertook a journey to the Empire himself.

Since these efforts were also unsuccessful, he made a fundamental political about-face: On the advice of Martin Luther, he decided to secularize the state of the Order, to give up the office of Grand Master and to transform Prussia into a secular duchy. He thus distanced himself from the Empire and gained support for his plan to secularise the Order's state from the King of Poland, whom he had previously opposed as Grand Master. In addition, Albrecht was a nephew of the Polish king through his mother Sofia and took the oath of fealty to King Sigismund I of Poland, in return for which he was enfeoffed with the hereditary dukedom in Prussia ("in" and not "of" Prussia, because the western part of Prussia was directly under the patronage of the King of Poland). The former Grand Master resided in Königsberg as Duke Albrecht I from 9 May 1525.

The institutions of the Holy Roman Empire did not recognize the secular Duchy of Prussia, but formally appointed administrators for Prussia until the end of the 17th century.

The branch of the Order in the Empire did not come to terms with the transformation of "its" Order state Prussia into a secular duchy. A hastily convened General Chapter installed the previous Deutschmeister Walther von Cronberg as the new Grand Master on 16 December 1526. In 1527 he received from the Emperor the enfeoffment with the regalia and the right to call himself Administrator of the Grand Mastership and thus to maintain the claim to ownership of Prussia.

It was not until 1530 that an imperial decree allowed Cronberg to call himself Hochmeister. This designation later gave rise to the abbreviated title of Hoch- und Deutschmeister. At the same time, Cronberg was proclaimed Administrator of Prussia and enfeoffed with the Prussian lands by Emperor Charles V at the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1530.

Cronberg then sued his former Grand Master, Duke Albrecht, before the Imperial Chamber Court. The trial ended in 1531 with the imposition of the imperial imperial oath against Duke Albrecht as well as the instruction to Albrecht and the Prussian Confederation to restore the Order's ancestral rights in Prussia. In Prussia, which lay outside the empire, the steps remained without effect. It received a Lutheran national church. Warmia, on the other hand, which had been withdrawn from the sovereignty of the Order since 1466, remained an ecclesiastical territory as a prince-bishopric and became the starting point of the Counter-Reformation in Poland.

Livonia until 1629

In 1561, the possessions of the Livonian branch of the Order, i.e. Courland and Semgall, were transformed into a secular duchy under the former Landmeister, Duke Gotthard von Kettler. The actual Livonia came directly to Lithuania and formed in the later state Poland-Lithuania a kind of condominium of the two parts of the state. The duchies of Prussia, Livonia, Courland and Semgall were now subject to Polish feudal sovereignty.

In the face of the Russian threat and represented by their knighthoods, northern Estonia with Reval and the island of Ösel (Saaremaa) submitted to Danish and Swedish sovereignty, respectively. In 1629, most of Livonia became part of Sweden as a result of Gustav II Adolf's conquests; only southeastern Livonia (Lettgallen) around Dünaburg (Daugavpils) remained Polish and became the voivodeship of Livonia, also called "Polish Livonia".

After the end of the Great Northern War, Livonia, together with Riga and Estonia, was incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1721 in the form of the so-called Baltic Sea governorates. Latgalia became part of the Russian Empire in 1772, and Courland and Semgallia only in 1795 in the course of the Polish partitions.

The Order in the Empire

After 1525, the sphere of activity of the Teutonic Order, apart from the scattered possessions in Livonia, was limited to its possessions in the Holy Roman Empire. Since the Reformation, the Order was triconfessional; Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed bailiwicks existed.

After the loss of its Prussian possessions, the Order succeeded in consolidating both externally and internally under Walther von Cronberg. At the General Chapter of Frankfurt in 1529, the Cronberg Constitution was issued, the future constitutional law of the noble corporation. Mergentheim became the residence of the head of the Order and at the same time the seat of the central authorities of the territories directly subordinate to the Grand Master (the Mergentheim Mastery).

Outside of this territorial rule, which adapted to the new conditions, the bailiwicks led by the land commanderies developed into largely independent entities. Some of them had the rank of imperial estates and ranked within the imperial register in the group of prelates. Often they became dependent on neighbouring noble families, who sent their sons to the order. In Thuringia, Saxony, Hesse and Utrecht, where the new doctrines had become firmly established, there were also Lutheran and Reformed brethren of the order who - following the corporate thinking of the nobility - were loyal to the Grand Master, also lived in celibacy and only replaced the vow formula with an oath.

After 1590, the High and German Masters were chosen from leading families of Catholic territorial states, above all from the House of Habsburg. This created new familial and political cross-connections to the German higher nobility, but also allowed the Order to become more and more an instrument of Habsburg domestic power politics.

Against this background, an inner change of the order began in the 16th century. A Catholic-influenced reform led to a return to its original orientation, and the rules of the order were adapted to the new circumstances. In the course of the 16th century, the nobility's thinking in terms of class, which tended to push for exclusivity, pushed back the importance of the mostly non-noble priest brothers. In modern times they had neither a seat nor a vote in the General Chapter. The pastoral care in the commends was often in the hands of members of other ecclesiastical orders. Since laymen with legal training worked in the chanceries of the order, this activity also fell away for priest brothers. As a result, their number had fallen sharply.

The leadership of the Order followed the demands of the Council of Trent and decided to endow new seminaries. This happened in Cologne in 1574 and in Mergentheim in 1606. The founder of the latter seminary was Grand Master Archduke Maximilian of Austria, on whose initiative Tyrol had also remained Catholic. In general, it can be noted that possessions belonging to the Teutonic Order remained Catholic even in predominantly Reformed areas, a fact which has had an effect up to the present day. External branches of the Order in Protestant areas played an important role in the pastoral care for Catholics passing through or for the few Old Believers who remained there. In some commends, the idea of the hospital brotherhood also re-emerged. Among other things, the order established a hospital in Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen in 1568.

The most important task of the order, which was still influenced by the nobility and its values, was the martial deployment of the knight brothers, who from the 17th century onwards also called themselves cavaliers, following the Italian model. The Turkish wars, which had been escalating since the 16th century, offered an extensive field of activity to a statutory defence of the Christian faith. Despite financial hardship, the Order made considerable contributions in this way to the - in the parlance of the time - defence of the Occident against the Ottoman Empire. Professed knights mostly served as officers in regiments of Catholic imperial princes and in the imperial army. In particular, the imperial infantry regiment No. 3 and the k.u.k. Infantry Regiment "Hoch- und Deutschmeister" No. 4 drew their recruits from the German territories of the Order. All fit knights had to serve a so-called exercitium militare. They served for a period of three years in the rank of officer in the border fortresses, which were particularly endangered by military campaigns, before they were allowed to take over further offices of the Order.

After the Thirty Years' War, a lively building activity developed in the commends of the Order. Castles, often combined with remarkable castle churches, and representative commendatory houses were built. Such buildings were erected in Ellingen, Nuremberg, Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen, Altshausen, Beuggen, Altenbiesen and in many other places. In addition, numerous new, richly furnished village and town churches were built, as well as secular functional buildings.

Territorial losses and restructuring in the 19th and 20th centuries

The Coalition Wars resulting from the French Revolution at the end of the 18th century were the cause of another major crisis for the Order. With the cession of the left bank of the Rhine to France, the bailiwicks of Alsace and Lorraine were lost completely, Koblenz and Biesen to a large extent. The Peace of Pressburg with France after the heavy defeat of the Austro-Russian coalition at Austerlitz against Napoleon in 1805 decreed that the possessions of the Teutonic Order and the office of the Grand and German Master should pass hereditarily to the House of Austria, i.e. Habsburg. The office of the Grand Master and with it the Order were integrated into the sovereignty of the Empire of Austria. Emperor Francis I of Austria, however, allowed the nominal status of the Order to continue. The Grand Master at this time was his brother Anton Viktor of Austria.

The next blow came with the outbreak of a new warlike conflict in the spring of 1809. On April 24, after the Austrian invasion of the Kingdom of Bavaria as a result of the Fifth Coalition War, Napoleon declared the Order in the Confederation of the Rhine dissolved. The property of the Order was ceded to the princes of the Confederation of the Rhine. In this way Napoleon intended to compensate the war effort of his allies in the war against the Coalition materially and to bind the princes thus more closely to the French Empire. The Order now only had the possessions in Silesia and Bohemia as well as the Bailiwick of Austria with the exception of the commanderies around Carniola, which had been ceded to the Illyrian provinces. The Ballei An der Etsch in Tyrol had fallen to the French vassal kingdoms of Bavaria and the kingdom in north-eastern Italy, which had emerged from Napoleon's Cisalpine Republic in 1805.

In the course of the secularization in the early 19th century, the Order lost most of its territories, although it had still been recognized as sovereign in the Imperial Deputation. But already in 1805, Article XII of the Peace of Pressburg stipulated that "The dignity of a Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, the rights, domains and incomes ... should be left hereditarily in person and in a straight male line according to the birthright to that Prince of the Imperial House whom His Majesty the Emperor of Germany and Austria will appoint". The Order had thus become part of Austria and the Habsburg Monarchy.

As a result of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the bailiwicks of Carniola and Tyrol fell to Austria and thus into the Order's sphere of control; however, a restoration of the Order's full sovereignty was no longer possible in view of the now insufficient assets.

In 1834, Francis I again renounced all rights from the Peace of Pressburg and reinstated the Order in its old rights and duties: by Cabinet Order of 8 March 1843, the Order became legally an independent ecclesiastical-military institute under the bond of an imperial direct fief. Only the Bailiwick of Austria, the Mastership in Bohemia and Moravia, and a small Bailiwick in Bolzano remained.

After the demise of the Danube Monarchy in the aftermath of the First World War, the Order was initially regarded in the successor states of the multi-ethnic monarchy as the Imperial Habsburg Order of Honour. Therefore, the responsible authorities considered a confiscation of the Order's assets as nominal property of the Habsburg Imperial House. For this reason, Grand Master Archduke Eugene of Austria-Teschen renounced his office in 1923. He had the Order's priest and Bishop of Brno Norbert Johann Klein elected coadjutor and at the same time resigned. This caesura proved to be successful: By the end of 1927 the successor states of the Danube Monarchy recognised the Teutonic Order as a spiritual order. The Order still comprised the four bailiwicks (later called provinces) in the Kingdom of Italy, the Czechoslovak Republic, the Republic of Austria and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

On September 6, 1938, the National Socialist German Reich Government issued a decree dissolving the Teutonic Order. In the same year, as a result of this decree, the Teutonic Order was dissolved in Austria, which had been annexed to the German Reich as Ostmark. In 1939, the same edict was applied in the so-called Rest of Czechoslovakia, the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which had been annexed by the German Reich. In the Italian South Tyrol, there were ideologically based attacks by local fascists on institutions and members until 1945.

In the "Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes" and the "Kingdom of Yugoslavia" (1918-1941), the Order was tolerated in the 1920s and 1930s. During the Second World War, its possessions, mostly located in the Slovenian territory, served as military hospitals. After 1945, members of the Teutonic Order were persecuted in the Federative People's Republic of Yugoslavia, not least as a result of the name, due to the war and post-war events. In the course of the abolition of all ecclesiastical orders here in 1947, the Yugoslav state authorities secularized the property of the Teutonic Order and expelled its members from the country.

After the Second World War, the decree of abolition of 1938 was annulled by state law in Austria in 1947 and the remaining property was restituted to the Order.

Members of the Order were also expelled from Czechoslovakia. In Darmstadt these members of the order founded a convent in 1949, which was abandoned in 2014. In 1953 a motherhouse was established for the sisters of the Order in Passau, in the former Augustinian monastery of St. Nikola (the sisters' part of the Order in Passau was legally supervised by Franz Zdralek). In 1957 the Order acquired a house in Rome as the seat of the Procurator General, which also serves as a pilgrims' house. In 1970 and 1988 the rules of the order were modified - also with regard to a better participation of the female members.

King Philip II. August of France besieges Acre (14th century miniature)

Hermann von Salza, the IV. Grand Master in the years 1210-1239; later historicizing depiction from a 16th century chronicle; the Grand Master's armour and headgear do not correspond to the period depicted.

Castle of the Kommende Ramersdorf near Bonn

Bell tower of the castle church of the baroque residence of the land commander of Franconia in Ellingen

Silver medal of the now dissolved Partin Bank Bad Mergentheim to the Teutonic Order. The obverse is a facsimile of the medal by Franz Andreas Schega. It shows Clemens August of Bavaria, Grand Master of the Teutonic Order 1732-1761. The reverse depicts the church of the Order in Mergentheim Castle.

The Order's Prussia, which remained after the 2nd Peace of Thorn in 1466, as well as the Masterdom of Livonia; Warmia, shown in pink, had become part of Royal (Polish) Prussia, but had a special status within it with extensive autonomy.

Treaty of the Teutonic Order with the Danish Queen Margarethe I. about the restitution of Gotland

Depiction of the Battle of Tannenberg in the Bern Chronicle by Diebold Schilling the Elder around 1483

The Order Balleys in the Empire

Acquisitions of the Teutonic Order in Prussia and of the Order of the Brothers of the Sword, united with it in 1237, in Courland and Livonia until 1260; the shaded areas are the disputed territories in Prussia and Schamaiten.

The Possessions, Headquarters and Acquisitions of the Teutonic Order in Prussia and the Livonian Union up to the Year 1410

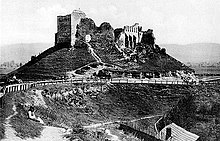

View of the Mariánské Lázn? above Feldioara in Romania (late 19th century), before the renovation and reconstruction 2013-2017.

Branches of the knightly orders in Outremer until 1291

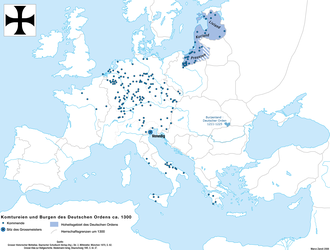

The Branches of the Teutonic Order in Europe around 1300

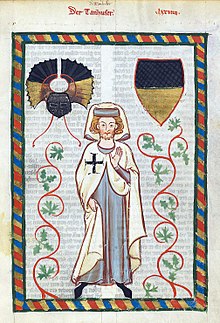

Tannhäuser in the white coat of the Teutonic Knights; miniature from the Codex Manesse c. 1300

South portal of the gothic Leech church in Graz

Headquarters and archives of the Order

The original seat of the Grand Master and thus also of the Order was its hospital in Acre. In 1220, the Order acquired Montfort Castle, which became the seat of the Grand Master after its reconstruction. In 1271 the castle was conquered by the Mamluks and the Grand Master returned to Acre. After the fall of Acre in 1291, under the Grand Master Konrad von Feuchtwangen, Venice became the main seat, then from 1309 under the Grand Master Siegfried von Feuchtwangen, Marienburg.

After their loss, Königsberg became the headquarters of the Order in 1457. From 1525/27, Mergentheim was mostly the official seat of the High and German Master. After the Order lost its sovereignty through the provisions of the Peace of Pressburg, the central residence of the Order was in Vienna from 1805 to 1923.

The then Coadjutor and later Grand Master Norbert Johann Klein moved the seat to Freudenthal in 1923. Since 1948 the seat of the Grand Master is again in Vienna. The Deutschordenshaus in Vienna, located behind St. Stephen's Cathedral, is also the seat of the Central Archives of the Teutonic Order and the Treasury of the Teutonic Order, which is open to the public.

The completely preserved documents of the Prussian State Archives Königsberg from the time of the Order are in the Secret State Archives Prussian Cultural Heritage. The documents from Mergentheim are in the State Archives Ludwigsburg. Further records are in the State Archives of North Rhine-Westphalia. and in the State Archives of Nuremberg. The state of Baden-Württemberg and the city of Bad Mergentheim are the sponsors of the Deutschordensmuseum in Bad Mergentheim.

On 4 July 2014, the Research Centre of the Teutonic Order was established in Würzburg.

·

Vienna

·

Bad Mergentheim

Marienburg Castle

Search within the encyclopedia