Tao Te Ching

The Daodejing (Chinese 道德經 / 道德经, pinyin![]() , W.-G. Tao4 Te2 Ching1, Jyutping Dou6dak1ging1) is a collection of chapters of sayings which, according to Chinese legend, originated with a sage named Laozi, who disappeared in a Western direction after writing the Daodejing. It contains a humanistic state doctrine that aims at liberation from violence and poverty and the permanent establishment of harmonious coexistence and ultimately world peace. The history of its origin is uncertain and the subject of sinological research. Notwithstanding other translations, Dao (道) means path, flow, principle, and meaning, and De (德) virtue, goodness, integrity, and inner strength (strength of character). Jing (經 / 经) refers to a canonical work, guide, or classical collection of texts. The two eponymous terms stand for something not ultimately determinable, the actual meaning of which the book seeks to point to. For this reason they are often left untranslated. The work is considered the founding scripture of Daoism. Although this encompasses various currents that may differ considerably from the teachings of the Daodejing, it is regarded as a canonical, sacred text by the followers of all Daoist schools.

, W.-G. Tao4 Te2 Ching1, Jyutping Dou6dak1ging1) is a collection of chapters of sayings which, according to Chinese legend, originated with a sage named Laozi, who disappeared in a Western direction after writing the Daodejing. It contains a humanistic state doctrine that aims at liberation from violence and poverty and the permanent establishment of harmonious coexistence and ultimately world peace. The history of its origin is uncertain and the subject of sinological research. Notwithstanding other translations, Dao (道) means path, flow, principle, and meaning, and De (德) virtue, goodness, integrity, and inner strength (strength of character). Jing (經 / 经) refers to a canonical work, guide, or classical collection of texts. The two eponymous terms stand for something not ultimately determinable, the actual meaning of which the book seeks to point to. For this reason they are often left untranslated. The work is considered the founding scripture of Daoism. Although this encompasses various currents that may differ considerably from the teachings of the Daodejing, it is regarded as a canonical, sacred text by the followers of all Daoist schools.

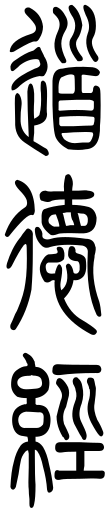

Dàodéjīng ( 道德經) - small seal writing

The contents

Dao and De

The present title of the work - "The Book of the Dao and of the De" - refers to the two central terms of Laozi's worldview. There are various translations of these two words; relatively common (e.g. in Debon) are "way" and "virtue", which were already in use in the 19th century. Richard Wilhelm considered the moralizing "virtue" to be aberrant and saw extensive correspondence with the terms "meaning" and "life," which earned him some criticism. The terms Dào and Dé are used in all directions of Chinese philosophy, but take on a special meaning in the Daodejing, where they were first used in the sense of a highest or deepest reality and a comprehensive principle. The Daodejing does not approach the Dao in a definitional way, but delimits it by means of negations: if it is not possible to state positively what it is, it is possible to state what it is not. As origin, through change forming elemental force and immanent connection of all being, the Dao pervades all appearances of the world, it permeates everything that exists and happens as a principle that opens up through deep insight into the appearances. Because it underlies all being, unlike partial thoughts and ideas, it is everlasting. The Daodejing illustrates this by means of parables. (1, 4, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 18, 21, 23, 25, 32, 34, 41, 53, 77)

"In the depth of man rests the possibility of a co-knowledge with the origin. If the depth is buried, the waves of existence pass over it as if it were not there at all."

- K. Jaspers: Munich 1957, p. 910

Man is able to connect with the Dao in silence and self-reflection. Then all phenomena reveal themselves to him in their true, unadulterated essence.

The origin of life is paraphrased in Laozi as female or maternal. The religious scholar Friedrich Heiler suspects that Laozi came from a mother-right cultural area.

By aligning his life with the Dao, a person receives his De. The De, in the language of classical Chinese, probably originally goes back to ideas of a power such as that associated in Shang Dynasty China with the figure of the shamans, who possessed a magical power associated with the idea of qi (氣 qì, Ch'i). The first part of the character 德 dé, 彳 chì with the original meaning "crossroads", indicates that it refers to the way one approaches people and things, which "path" one takes. 直 zhí means "on a straight path"; eyes also occur in this character, thus to orient oneself according to the right path. The executive organ is the heart 心 xīn, which includes all the functions of the spirit-soul (mind, consciousness, perception, sensation). The ancient dictionary Shuowen Jiezi explains the meaning thus, "Reaching out to (others) on the outside, reaching out to one's self on the inside." What is meant, then, is the appropriate, sincere, straight, direct path, to one's own heart and that of others, the ability to be able to meet oneself and others, and to enable genuine touch.

The Wise Man

A good part of the Daodejing deals with the figure of the sage, saint (Shengren, 聖人 / 圣人, shèngrén) or called one, who has brought the consideration of the Dao to mastery in his work. Numerous chapters end with what lessons he drew from the observations he made. (2, 7, 22, 49, 58, 64) Of course, especially a head of government should be guided by this example, since his decisions influence the fate of many.

Particular attention is paid to the setting aside of his own self up to the point of self-emptying. The very fact that he does not want anything of his own conditions the completion of his own. (7) He does not claim his products and works for himself. Rather, he subsequently withdraws (which is why he does not remain abandoned). (2) The Dao of heaven is precisely the non-residence in the accomplished work, which underlines the positive efficacy of this procedure. (9) This comes about all by itself, without arguing, without talking, without waving. (73) The sage dwells in action without action (Wu Wei). Its value lies in instruction without words, which is especially difficult to achieve (43). It is not further explained, so one must use one's own imagination to give meaning to this expression.

Wu Wei

| Characters | Pinyin | Jyutping | Meaning | ||

| 無 | 無 | 无 | wú | mou4 | without, not, no |

| 爲 | 為 | 为 | wéi | wai4 | (to) do, (to) act |

Source: See below

A basis that results from the knowledge about the Dao is the non-action (Wu Wei). This non-intervention in all areas of life seems utopian and unworldly to the Western reader. It is based on the insight that the Dao, which is the origin and goal of all things, by itself pushes to the balance of all forces and thus to the optimal solution. For Laozi, doing is a (deliberate) deviation from the natural equilibrium through human intemperance. Every deviation therefore results in a (non-intentional) counter-movement that seeks to restore the disturbed balance.

"The very unintentionality, which in its simplicity is the enigma, has perhaps never in philosophizing been made so decidedly the basis of all truth of action as by Lao-tzu."

- K. Jaspers: Munich 1957, p. 908

Whose government is quiet and unobtrusive, whose people are sincere and honest. Whose government is astute and strict, whose people are deceitful and untrustworthy. Misfortune is what happiness is based on, happiness is what misfortune lurks on. But who can see that it is the highest thing if there is no order? For otherwise order turns to marvels, and good turns to superstition. And the days of the delusion of the people are truly long. (58)

By doing what spontaneously corresponds to natural conditions, man does not interfere with the work of the Dao and thus chooses the beneficial path. According to Laozi, a person who refrains from deliberate action becomes yielding and soft. He places himself in the lowest place and thereby attains the first place. Because he is soft and pliable like a young tree, he survives the storms of time. Because he does not quarrel, no one can quarrel with him. (66) In this way a man lives in accordance with the origin of life. But life also includes death in itself. And yet Laozi says that he who knows how to lead life well has no mortal place. (50)

The goodness of water

The Daodejing recognizes the qualities of the Dao in water. There is nothing softer and weaker than water. But it's incomparably hard on the hard. (78) The soft and weak triumph over the hard and strong. (36) A new-born creature is soft and weak, but when it dies it is hard and strong. (76) Let the strong and great be below. So also is water: because it can hold itself down well, mountain streams and valley waters are filled with streams and seas. So also the Dao behaves towards the world. (66, 32) The Dao is always flowing,(4) even overflowing,(34) and gives harmony to the ever-ascending beings. (42) Let supreme goodness be like water: it benefits all beings without strife. (8) Nor let the Dao deny itself to them; (34) nor the sage. (2)

Morality is paucity

A person of the Dao refrains from personal desires and cravings as well as from socially accepted goals and rules. In this respect, he also no longer tries to be morally good. Morality, for Laozi, is already the final stage of the decay of motives: if SENSE [Dao] is lost, then LIFE [De]. ... then love. ... justice. ... custom. Custom is fidelity and paucity of faith and the beginning of confusion. (38) Only when the Dao is lost do men invent manners and precepts, which distance them still further from natural action. The government should not encourage this: "Put away morality, throw away duty, and the people will return to filial duty and love. (19)

Here Laozi stands in strong contrast to the influential moral teachings of Confucius, who upheld and cultivated custom and law as manifestations of the ultimate truth. Similarly, Confucius says that in the art of government the "names" (words) must first be put right, which Laozi again says are not to be dispensed with in order to survey all things,(21) but they do not meet their eternal essence. (1) He recommends renunciation: make rare the words, and all will go by itself. (23) SIN as the Eternal is nameless simplicity. (32) But many words exhaust themselves in this. It is better to preserve the inner. (5)

Philanthropy

However, the Daodejing does not only call for non-intervention, but also for standing up for one's fellow man, for kindness and forbearance, similar to the Christian love of one's neighbour and love of one's enemies. See chapter 49 (in the translation by Viktor Kalinke):

"The heart and mind of the wise are not always the same...

The heart and mind of the people he raises to his

I meet good with good

the evil also good

Virtue is goodness

To the sincere I meet sincerely

the insincere also sincere

Virtue is sincerity

Reigns the wise under heaven:

restrainedly he holds back

intervenes, to get heart and mind after

with all under heaven to agree on simple things

Among the people all strain their ears and eyes

The wise man meets them like children"

Government

Almost half of the 81 chapters of the Daodejing explicitly refer in some way to the people, the consequences of different ways of governing, and the relationship with the military. What follows, therefore, is a compilation of key political positions, without detailing the arguments supporting them, and insights and recommendations for the potential ruler (or ruleress, king, head of government...) who may hope to gain just such information from this book.

Ways of ruling

Do not favor the efficient, do not value goods that are difficult to obtain, do not arouse covetousness, and the people do not quarrel (compete), steal and rebel. A wise government strengthens the body and vitality of the people, who, however, in the spirit of Wu Wei, remain without knowledge and without desires, to the weakening of the will and the desires. 3 The Daodejing rejects enlightenment and prudence. To order the state by prudence is to rob the state. 65 The conduct of the chiefs (太上 tài shàng) is hardly known. Trust against trust. Works were performed in utmost secrecy, and no one saw any outside influence in them.

Inferior modes of rule, on the other hand, evoked closeness and fame, fear or even contempt. 17 And with the decline of harmonious relations, things that actually seemed self-evident would suddenly become important in order to counteract the great falseness, discordant relatives, and rebellious mischief. 18 Conversely, the people would have a hundredfold benefit with the abandonment of all paradigms, such as wisdom, prudence, benevolence, righteousness, skill, and usefulness. But

...has the effect of uniting us.

Behold the simplicity, embrace the simplicity (樸 pǔ).

Of little self-interest, of few desires. 19

Simplicity and submission to the people

The more prohibitions, use of tools, skills, directives and regulations, the poorer the people, and in the state and the homeland the evil is rampant. Love silence, do nothing, have no desires, and the people will develop by themselves, straighten themselves up, become rich and yet simple. 57 One should rule unobtrusively, not impose one's order, otherwise the order and the good will turn into their opposite, and the days of man's delusion will be continued all the more. 58 The nameless simplicity would bring about desirelessness, and the world would calm itself. 37 A great state, he said, should be managed with extreme caution, as small fish are fried, so as not to trouble the dead or harm the living. 60 A great state, a regional power, should keep itself below in order to raise the people unitedly. 61 Let the wise man rank himself among the people, and let the world not tire of supporting him with joy. 66

Distribution issue

Just don't imagine anything: Hoarding precious things in abundance in splendid palaces, living lavishly and bearing arms, but the fields are neglected and the granaries empty-this is called theft (盜 dào), not Dao! 53 The people should not have to live in poverty and confinement. There is a strong warning against rebellion. 72 The people starve, are difficult to order, and die recklessly because their superiors consume abundance of taxes (redistribution upward) and are overambitious and wasteful. 75 Let man's way diminish what is not sufficient to offer to that which has abundance. But who is able to compensate in the world? Only he who has the way. 77

Conflicts and military

The Commander of the Armed Forces should in no way, for his own sake, take the world lightly or lose his cool. Levity, then one loses the base. Excitement, then one loses sovereignty. 26 A helper of the Way does not by arms compel the world. Whose affairs are left to return. Wanted is peaceful conflict resolution, far from coercion and the horrors of war. 30 Swords to plowshares is the Dao. No doom greater than not knowing sufficiency. 46 Towards enemies, a military de-escalation strategy is recommended. The melancholic win, mind you. 69 Vigilante justice is a dangerous presumption. 74 If one reconciles great enmity, how does one also reconcile the rest? He who has efficacy keeps treaties, and yet asks nothing of men. 79

Frugality, softness and social vision

Without inner unity, anything would have to perish. The low is the foundation of the highest, especially kings are aware of that. 39 No means is better than thrift, thereby early provision and gathering of forces, then there is nothing that does not succeed, and the people and their state may exist for a long time. 59 The ruler is the protecting power of all people, also of the "unkind". 62 One meets undesirable developments with much patience, knowing that they will pass their zenith. Soft and weak overcome hard and strong. Fish cannot escape from the depths. The instruments of the state, therefore, could not be shown to men. 36 The soft and the weak overcome the hard and the strong, no one does not know this, no one is able to apply it. A wise man once said: He who takes upon himself the misfortune of the state, this is the king of the world. 78 Small states may have only a few people. But no one develops armament, knowledge, and technology. Let [the people's] food be sweet, their clothing beautiful, their dwelling peaceful, their customs cheerful. Let no one travel far away until old age. 80

The Daodejing and Daoism

The religion known today as Daoism, which worships Laozi as a god (see Three Pure Ones), is not a direct implementation of the Daodejing, although it has points of contact with it and understands the text as a mystical instruction for attaining the Dao. However, it also derives from the ancient shamanistic religious traditions (see Fangshi) of China and the field of Chinese natural philosophy, whose wisdom and vocabulary are probably also cited in the Daodejing. In the reading of a state and social doctrine, the text was understood as a guide for the saint or sage, by which was meant the ruler who contributes to the welfare of the world through his recollection of the Way and the radiance of his virtue.

Furthermore, by Chinese commentators such as Heshang Gong, Xiang Er, and Jiejie around 200 to 400 A.D., a view was systematically formulated that conceived of the text as a mystical doctrine for the attainment of wisdom, magical powers, and immortality, and closely related to alchemical attempts to find an elixir of immortality.

Questions and Answers

Q: Who wrote the Tao Te Ching?

A: The Tao Te Ching was written by a man named Laozi, also known as Lao Tzu.

Q: What does the title of the book mean?

A: The title of the book translates to "The Book of the Way and its Virtue."

Q: When was the Tao Te Ching written?

A: It is believed that the Tao Te Ching was written around 600 BC.

Q: What is its importance in Chinese culture?

A: The Tao Te Ching is an important text to Chinese culture, and it is very important in Chinese philosophy and religion. It is also considered to be the main book for Taoism, which combines both philosophy and folk religion.

Q: How did it influence other philosophies in China?

A: The teachings found within the Tao Te Ching have had a significant influence on other philosophies in and around China.

Search within the encyclopedia