Tadeusz Kościuszko

![]()

Kosciuszko, Kościuszko and Kosciusko are redirections to this article. For other meanings, see Kosciusko (disambiguation).

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( ![]() ) (* February 4, 1746 in Mereczowszczyzna, Poland-Lithuania, now Belarus; † October 15, 1817 in Solothurn, Switzerland) was a Polish military engineer who became a Polish national hero in the Russo-Polish War of 1792 and especially as the leader of the 1794 uprising against the partitioning powers of Russia and Prussia, named after him. From 1777 to 1783 Kościuszko also fought on the American side in the American War of Independence. He espoused the ideals of the Enlightenment and supported the worldwide movement to abolish slavery. The status of a national hero is attributed to him not only in Poland, but also in Belarus, the United States and partly in Lithuania.

) (* February 4, 1746 in Mereczowszczyzna, Poland-Lithuania, now Belarus; † October 15, 1817 in Solothurn, Switzerland) was a Polish military engineer who became a Polish national hero in the Russo-Polish War of 1792 and especially as the leader of the 1794 uprising against the partitioning powers of Russia and Prussia, named after him. From 1777 to 1783 Kościuszko also fought on the American side in the American War of Independence. He espoused the ideals of the Enlightenment and supported the worldwide movement to abolish slavery. The status of a national hero is attributed to him not only in Poland, but also in Belarus, the United States and partly in Lithuania.

.jpg)

Tadeusz Kościuszko, painting by Karl Gottlieb Schweikart (after 1802)

Live

Youth and education

Kościuszko was born in the village of Mereczowszczyzna in Polesia as the youngest child of Ludwik Kościuszko, a Brest official belonging to the Polish landed gentry (szlachta). The Kościuszkos had belonged to the Szlachta since 1509, when King Sigismund I had given the Siechnowicze estate to his secretary Konstanty as a reward for loyal service and awarded the family the coat of arms of the Roch III Polish armorial society. Together with his elder brother Józef, Tadeusz attended a Piarist college in Lubieszów in what was then Volhynia Voivodeship, now Lyubeshiv, Ukraine, from 1755. He then studied at the Szkoła Rycerska Royal Military College in Warsaw from 1765. In addition to military subjects (including drawing fortifications), mathematics, Polish and European history, geography, physics, chemistry, German and French were taught there.

Kościuszko proved to be a brilliant student, became an ensign after a year and attended in-depth courses in engineering. He subsequently became an instructor and was promoted to captain. He moved to Paris in 1769 on a royal scholarship. There he studied at what was then the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, a predecessor institution of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. As a foreigner, he was barred from attending the École royale du génie in Mézières, a school for military engineers, but he was able to continue his military studies by taking private lessons from lecturers at this school. His stay in pre-revolutionary France, where he became familiar with Enlightenment thinking, had a lasting influence on his political views.

American War of Independence

In 1774 Kościuszko returned to Poland, but found no employment in the severely depleted army of the country scarred by the partition of 1772. After a stay in Dresden, he went back to Paris in the autumn of 1775 in search of a job. There the writer Pierre de Beaumarchais was soliciting support for the American Revolution. Beaumarchais had established the front company Roderigue Hortalez & Co. with seed money from the French government to serve the smuggling of arms and munitions to America. Kościuszko sailed for America in late June 1776 on a ship belonging to Beaumarchais's company, along with a French and a Saxon officer. Upon Kościuszko's arrival in Paris, Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin, who would act as American commissioners in France shortly thereafter, had not yet arrived there, so Kościuszko, unlike later foreign war volunteers, was unable to obtain a letter of introduction to Congress. However, he is said to have carried a letter of introduction from Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski to Major General Charles Lee.

Kościuszko arrived in Philadelphia in 1776 and became a colonel in the pioneer corps of the Continental Army. He designed the fortifications of Fort Billingsport and Fort Mercer on the Delaware River near Philadelphia, and in 1777 was assigned to the "Northern Army" under Horatio Gates. Kościuszko took command from this time to establish various forts and fortified military camps on the Canadian frontier. In 1777, he participated in the Battle of Ticonderoga and the Battle of Saratoga. Fortifications built by Kościuszko on Bemis Heights are said to have contributed significantly to the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga, which is considered a turning point in the War for Independence. As historian Edward Channing noted, "The credit for Saratoga goes to Horatio Gates, and with him Daniel Morgan, Benjamin Lincoln, and Tadeusz Kościuszko."

From 26 March 1778 until the summer of 1780, Kościuszko fortified West Point on the Hudson River. The planning of this fort had initially been assigned to the Frenchman Louis de la Radière. Since Kościuszko had been appointed by Congress as chief engineer of West Point, but la Radière still considered himself in charge and, moreover, a more competent engineer, friction arose between the two engineers on the site. After George Washington initially thought to solve the problem by ordering Kościuszko to Army headquarters, a letter from Major General Alexander McDougall, who spoke in favor of Kościuszko, moved him to relieve la Radière of his duties at West Point instead. Dave Richard Palmer, a later superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, described West Point as built according to Kościuszko's plans as a fortress that was far ahead of its time. La Radière had wanted to build an elaborate Vauban-style structure that did not fit Washington's pressed schedule and would have been too costly and materials-intensive for the Americans' means.

After finishing work at West Point, Kościuszko was ordered (by Washington's letter of August 3, 1780) to the southern theaters of war and appointed engineer general of the Southern Army. Kościuszko's works of genius, particularly the construction of flatboats, played a significant role in General Nathanael Greene's "Southern Army," enabling it to evade the forces of British General Charles Cornwallis until the arrival of reinforcements and eventually pushing them north, where the British were defeated at the Battle of Yorktown.

From 1779 until the end of the War of Independence, Kościuszko was attached as an orderly to Agrippa Hull of Northampton (Massachusetts) (1759-1848). Hull's parents were among the few African American residents of Northampton and among the even smaller number among those who had won their freedom from slavery. The friendly bond with Hull is said to have contributed to Kościuszko's "increasing dismay that white Americans were fighting for universal principles that they were denying to half a million blacks," according to historians Nash and Hodges in their study of the lives of Thomas Jefferson, Kościuszko, and Hull. When Kościuszko left the United States, Jean Lapierre, an African American, accompanied him to Poland as an aide-de-camp. The historian and journalist Alois Feusi concluded in an article on the 150th anniversary of Kościuszko's death in the NZZ that Kościuszko had known very well "that the idea of the superiority of the white race is a pipe dream".

The United States Congress granted Kościuszko the rank of brigadier general and U.S. citizenship in 1783. That same year, he became a charter member of the Society of the Cincinnati, an order founded by American officers and named after Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus as a paragon of republican virtue. At the conclusion of the American War of Independence, Kościuszko, whom the new government had not yet been able to pay directly, received a credit of $12,280 for his services, with an annual payout of 6% interest and entitlement to 500 acres of land should he settle in the United States.

Leader of Polish troops, Kościuszko Uprising.

→ Main article: Kościuszko Uprising

In 1784 Kościuszko returned to the family seat in Siechnowicze in the then Brześć Litewski Voivodeship. After joining the royal army, he was appointed a major general by Polish King Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski in 1789. Kościuszko greatly welcomed the republican movement, the reforms carried out from 1788 to 1792, and the constitution adopted on 3 May 1791. Early on, he participated alongside Józef Poniatowski in plans for intervention against the partitioning powers of Russia and Prussia. In 1792 he was eventually one of the leaders of the Polish forces against the Russian invasion of Poland, which was directed against the liberal course of the Polish parliament and led to the outbreak of the Russo-Polish War of 1792. Poland was defeated by the imperial forces and the defeat was followed by the second partition of Poland by Russia and Prussia. Kościuszko then fled to Electoral Saxony. Arriving in Leipzig at the turn of 1792/1793, a French diplomat presented him with the certificate of honorary citizenship of France, which the French National Assembly had conferred on him in August 1792, along with George Washington, the Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and other notables. Kościuszko traveled to Paris as late as January 1793 in the hope of obtaining French support for Poland, arriving there just at the time of Louis XVI's execution. During his stay, he met with leading French revolutionaries, including Robespierre. After months of negotiations, however, Kościuszko concluded that the revolutionaries were only interested in weakening Prussia in the First Coalition War by creating a diversion in Poland, and left empty-handed.

In 1794 Kościuszko returned and led the Poles' fight for freedom against Russia and Prussia in the Kościuszko Uprising, named after him. For this he had himself sworn in as "dictator" in Kraków according to Roman law. In the Battle of Racławice on 4 April 1794, Kościuszko's forces defeated militarily superior Russian troops. After the successful use of peasants armed with war scythes in this battle, Kościuszko is said to have removed his general's uniform and donned a sukmana, a simple peasant dress, in honor of the peasants. The memory of the victory of the "reapers" in the Battle of Racławice, which was perceived as a sensation, subsequently acquired great symbolic significance for the Polish nation after the partitions of Poland. The Battle of Szczekociny of 6 June 1794, on the other hand, ended in defeat, as did the Battle of Maciejowice of 10 October 1794, in which Kościuszko was wounded and fell into Russian captivity. With the Battle of Praga and the massacre of the Warsaw civilian population by Suvorov's troops, the uprising was finally put down a month later.

For the uprising of 1794 Kościuszko had also solicited the support of the Jewish population. Already the day after he had announced the uprising on March 24 in the marketplace of Krakow, he gave an address in the Jewish quarter of Kazimierz. In it he assured the Jewish community that he was fighting for the good of all the inhabitants of his fatherland, and that the Jews were an important part of those inhabitants. He asked them for war volunteers and for financial support. Both were granted to him; Berek Joselewicz, who together with Józef Aronowicz raised a Jewish cavalry unit, became especially well known. Kościuszko granted this the status of a regular regiment and appointed Joselewicz colonel. Many soldiers of this regiment fell in the Battle of Praga.

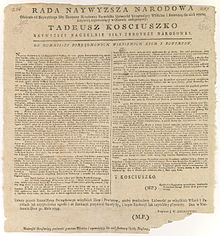

Kościuszko's status as a "peasant liberator" was consolidated by a decree known as the Połaniec Proclamation (Polish: Uniwersał Połaniecki) of May 1794, which, as a step towards the general liberation of the peasants, stipulated, among other things, that peasant servitude should be reduced. According to a publication by the historian Markus Krzoska on Kościuszko's path to becoming a national hero, the practical effect of the proclamation was "nil because of the further development of the uprising", but the symbolic significance for the following decades should not be underestimated.

Kościuszko spent two years in Russian captivity. After the death of Tsarina Catherine II, he was pardoned by her successor Paul I, who showed Kościuszko goodwill without relinquishing Russia's claim to power in occupied Poland. Since he was thus able to obtain the liberation of 12,000 Poles imprisoned in Russia, Kościuszko recognized Paul I as Polish sovereign for the time being for political reasons.

Exile

United States

After being released from captivity, Kościuszko went into exile, first to the United States. He stayed there until 1798. During this time he was in close contact with the American "founding father" Thomas Jefferson. Towards the end of his stay, he drew up a will with Jefferson's support. In it, he signed over his American fortune to Jefferson with a mandate that the funds be used to free and educate slaves, specifically Jefferson's own slaves. As recently as a month before his death in 1817, Kościuszko reminded Jefferson of this intended use by letter. Kościuszko, however, had later written three more wills. Although Kościuszko's 1817 letter to Jefferson suggests that he still considered his 1798 American will valid, Kościuszko had already revoked all previous wills in an 1816 will. The fact that Jefferson did not take over the execution of Kościuszko's will thereafter, delegated it to others, and ultimately did not ransom his own slaves or those of others, even though he himself had spoken out against slavery in the past, is evaluated differently by historians. Nash and Hodges, for example, assume that Jefferson feared the conflicts he could trigger with such an action, while Annette Gordon-Reed sees the legal difficulties due to the conflicting wills as decisive. Indeed, a succession of lawsuits ensued that lasted until 1852, when the Supreme Court ruled that the 1798 will had been overturned by that of 1816.

France

In 1798 Kościuszko went to France. He hoped to liberate Poland alongside the French and with Jan Henryk Dąbrowski's and Karol Kniaziewicz's Polish legions. However, this did not fit Napoleon Bonaparte's plans, and since the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire VIII, Kościuszko had also inwardly turned away from Napoleon. Kościuszko was then living, according to Adele Tatarinoff, "closely guarded by the police," in Paris and its environs. From 1801 to 1815 he lived with the family of Peter Josef Zeltner of Solothurn, who had been the first Helvetic envoy to Paris from 1798 to 1800, and at his country estate of Berville near Fontainebleau. Kościuszko led a domestic life with the Zeltner family at Berville, spending several hours each day teaching their three children. Because Peter Josef Zeltner was often absent and Kościuszko was close to his wife Angélique (Angelica Charlotte Drouin de Vandeuil de Lhuis), he was rumored to be having an affair with her and even that he was the father of the youngest daughter named after him, Thaddea. In any case, Kościuszko, who disliked the attention of Parisian society, preferred country life in Berville and tried to avoid the limelight there.

In October 1806, after he had entered Berlin following the Battle of Jena and Auerstedt, Napoleon asked Kościuszko, through his Minister of Police, Joseph Fouché, to come to him to assist him in moving on to Poland. Kościuszko, however, would not comply with this request without certain guarantees from Napoleon for Poland: Napoleon should agree to restore Poland and grant a constitution with equal rights for all citizens. Fouché could not persuade Kościuszko to follow him without such guarantees, even with threats. As a result, Fouché had a forged letter purporting to be from Kościuszko sent to the newspapers, declaring in pathetic terms Kościuszko's support for Napoleon. Not only Kościuszko, but also Napoleon himself condemned this forgery. After Kościuszko subsequently sent a letter to Fouché demanding for Poland a constitutional monarchy on the model of England, freedom for the peasants, and the restoration of Poland to its borders before the three partitions of Poland, Napoleon called him an "idiot" and did not consider him further. With the Duchy of Warsaw, Napoleon eventually established a Polish rump state as a protectorate of the First French Empire, which existed until 1815.

After the fall of Napoleon, Russian Tsar Alexander I granted Kościuszko an audience at Russian headquarters in Paris on 3 May 1814. He is said to have embraced Kościuszko and promised Poland a happy future. However, Kościuszko would not settle for Congress Poland as the result of negotiations at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. After a brief further audience with the Tsar on 27 May 1815, Kościuszko met Alexander's foreign minister Adam Jerzy Czartoryski in Vienna on 31 May, who tried to convince Kościuszko of the solution reached. This Czartoryski did not succeed in doing; Kościuszko declared that "his caring love belonged to the whole vast Polish Empire and not merely to the piece of land now pompously called the Kingdom of Poland". In particular, he was concerned that his homeland of Lithuania (Grand Duchy of Lithuania) should again be included in the Kingdom of Poland. After the failure of his efforts in this regard, Kościuszko remained in exile, as he did not want to legitimize the new rule in his homeland by his presence.

Switzerland

A return to France under Louis XVIII, where revolutionaries like him were persecuted, was out of the question for Kościuszko. Alex Storozynski cites as another reason that Angélique, the wife of Kościuszko's longtime host in France Peter Josef Zeltner, was dying. Kościuszko settled in Switzerland. He was able to take up residence with Xaver Zeltner in Solothurn, a brother of Peter Josef Zeltner. Xaver Zeltner shared Kościuszko's enlightened worldview. He belonged to the Solothurn Great Council from 1810 to 1814 as a member of the liberal opposition, was subsequently imprisoned for months without trial after the restoration of pre-revolutionary conditions, and had only been at liberty for a few weeks when Kościuszko arrived.

In Solothurn Kościuszko distinguished himself as a "benefactor and philanthropist" who, in the times of famine following the "year without a summer" in 1816, granted alms to all the needy who surrounded the Zeltners' house - and in doing so ignored a ban on begging which, in Solothurn from the beginning of 1817, imposed fines on those who donated.

On 15 October 1817 Kościuszko died in Solothurn. The cause of death is given as influenza or a stroke. He was buried separately: his entrails were interred in the cemetery of Zuchwil. Kościuszko's heart, which he had bequeathed to Xaver Zeltner's daughter Emilie, was kept in a specially made urn; this was later located in Vezia near Lugano, where Emilie lived as the wife of Giovanni Battista Morosini, then in the Polish Museum in Rapperswil, and meanwhile in the chapel of the Royal Castle in Warsaw. His embalmed body was first buried in the Jesuit Church in Solothurn and in 1818 transferred to the royal crypt of the Wawel Cathedral in Krakow.

.jpg)

Kościuszko's apartment in Solothurn, today Kościuszko Museum

_b_013.jpg)

Kościuszko in the last years of his life.

"Tsar Paul I visits the captured Kościuszko". Engraving by Thomas Gaugain after Aleksander Orłowski (1801)

The Połaniec Proclamation

Jan Matejko: "The Battle of Racławice". History painting from 1888

George Washington awards Kościuszko the Order of the Cincinnati in 1783 (A tempera by Michał Stachowicz, 1818)

Fort Clinton (West Point), fortified by Kościuszko. In the background the Kościuszko statue of West Point.

Coat of arms of the Kościuszko family (Roch III)

Social positions

Kościuszko was a "man of the Enlightenment" and firmly convinced of republican and democratic principles. He read Jean-Jacques Rousseau and was in contact with Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, whose views he shared on many points.

Despite a deistic attitude and his commitment to a "universal religion of all good people", Kościuszko also remained influenced by his Roman Catholic upbringing. He is said to have prayed every morning, and he was always respectful of the Catholic Church in public.

Kościuszko always spoke out clearly in favour of tolerance and was open to other religions and peoples. Xaver Zeltner, in whose house in Solothurn Kościuszko spent the last years of his life, said of him that his heart beat "for the whole world". In a letter to General Nathanael Greene in 1786, Kościuszko wrote that the "barriers of our affection for the rest of mankind are constricted by prejudice and superstition." Affection, he argues, should be shown to all respectable people - "let him be Turck or Polander, American or Japon". Alex Storozynski concludes in his biography that Kościuszko, who stood up "for peasants, Jews, Indians, women and all those discriminated against", was a "true prince of tolerance".

Search within the encyclopedia