Battle of Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo

Part of: Summer Campaign of 1815 (Seventh Coalition)

Battle of Waterloo

Painting by William Sadler (June 1815)

Battles of the Wars of Liberation (1813-1815)

Spring campaign 1813

Lüneburg - Möckern - Halle - Großgörschen - Gersdorf - Bautzen - Reichenbach - Nettelnburg - Haynau - Luckau

Autumn campaign 1813Großbeeren

- Katzbach - Dresden - Hagelberg - Kulm - Dennewitz - Göhrde - Altenburg - Wittenberg - Wartenburg - Liebertwolkwitz - Leipzig - Torgau - Hanau - Hochheim - Danzig

Winter campaign 1814Épinal

- Colombey - Brienne - La Rothière - Champaubert - Montmirail - Château-Thierry - Vauchamps - Mormant - Montereau - Bar-sur-Aube - Soissons - Craonne - Laon - Reims - Arcis-sur-Aube - Fère-Champenoise - Saint-Dizier - Claye - Villeparisis - Paris

Summer campaign of 1815Quatre-Bras

- Ligny - Waterloo - Wavre - Paris

The Battle of Waterloo [ˈvɑːtɐloː] of 18 June 1815 was Napoleon Bonaparte's last battle. It took place about 15 km south of Brussels near the village of Waterloo, which was then part of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands and is now in Belgium.

The defeat of the French led by Napoleon against the allied troops under the English General Wellington and the Prussian Field Marshal Blücher ended Napoleon's rule of the Hundred Days and led to the end of the French Empire with his final abdication on 22 June 1815.

After this second complete military defeat within a short period of time, more stringent peace terms were imposed on France in the Second Peace of Paris. Napoleon himself was taken as a prisoner of war of the British to the Atlantic island of St. Helena, where he died as an exile on 5 May 1821.

The phrase "experiencing one's Waterloo" as a synonym for total defeat has its origins in this battle.

In French it is called Bataille de Waterloo (or more rarely Bataille de Mont-Saint-Jean); in English Battle of Waterloo. In Germany, the name Battle of Belle-Alliance was also common until the 20th century.

Before the Battle of Waterloo, the Congress of Vienna ended on 9 June 1815 with the signing of the Congress Act.

Preparations

Napoleon took supreme command of the army, but could not fall back on his old team: Marshal Louis Alexandre Berthier, his former chief of staff, was dead, and he regarded Marshal Joachim Murat as a traitor. Other marshals refused to serve, either because of age or because they had taken an oath of allegiance to the new king, Louis XVIII. Napoleon's appointments in 1815 are often criticized by historians. Marshal Nicolas-Jean de Dieu Soult, an able commander in his own right, became chief of staff, although he had no training for it. Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy was first to lead the cavalry, for which he was particularly suited. He was later given command of the right wing of the army, although he had never commanded even one corps. The left wing was entrusted to Marshal Michel Ney, whose defection from the Bourbons and transition to Napoleon had been of the greatest importance in the latter's triumphal march to Paris. Ney was considered a fighter, but not a thinker. Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout, arguably the ablest of the marshals, stayed behind as Minister of War to hold Paris for the Emperor.

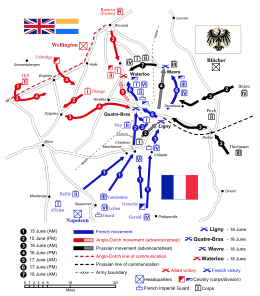

Through French sympathizers in the Netherlands, Napoleon had a clear idea of the troop disposition of his enemies. The armies were grouped in loose corps formation. The Prussians were in the Liège - Dinant - Charleroi - Tienen area. Wellington's army, which included Dutch, Hanoverian, Brunswick and Nassau units as well as British, was in the Brussels - Ghent - Leuze - Mons - Nivelles area. The massing of such an army could take days. The supply lines of both armies diverged, those of Wellington ran northwards, those of Blücher eastwards into Germany. In the event of any surprise attack that would have forced them to retreat, the allies would fall back along these routes. Napoleon wanted to strike first one army, then the other, without having to worry about the other. Napoleon's formation was ideally aligned for such a move. Two wings under Ney and Grouchy were to precede the army, and Napoleon was to follow in the centre, throwing the weight on either flank as he chose.

On the 15th of June the French army crossed the frontier into the Netherlands, and at nightfall Napoleon took up his quarters at Charleroi. His army was massed and stood between the allies. During dinner Wellington learned from the Crown Prince of the Netherlands that French scouts had reached Quatre-Bras (19 km south of Waterloo), an important road junction on the army's way to meet Blücher. He had anticipated a bypass on his right flank and had therefore begun to mass his army at Nivelles (Nivelles is 11 km west of Quatre Bras, 22 km west of Sombreffe and 16 km southwest of Waterloo). The Dutch commander at Quatre Bras had realised the importance of the crossroads and disobeyed orders to move to Nivelles. Two brigades now held this crossroads, 33 km from Brussels. It could be held by the Dutch, the Nassau and gradually arriving British and Brunswick reinforcements throughout 16 June (Battle of Quatre-Bras).

Ney, seeing before him a slight slope leading up to the cross-roads, supposed that, though this was held only by weak forces, yet behind it, concealed, lay the allied army in full strength. His experience in Spain had taught Ney to refrain from attacks on Wellington in prepared positions. Thus he made only reconnaissance attacks in the morning, and missed the chance of taking the crossroads before the arrival of the reinforcements. On the same day the Prussians faced the French attack in a previously reconnoitred position and were defeated in the battle of Ligny. Napoleon was unable to win a decisive victory, however, as the French I Corps received conflicting orders on the march from Quatre Bras to Ligny, and thus could not be used at either the Battle of Quatre Bras or Ligny. Thus, the Prussian army was able to avoid annihilation and retreat largely intact.

Field Marshal Blücher had been wounded in the battle and almost captured. The command was therefore led the following night by his Chief of Staff, Lieutenant General von Gneisenau, who ensured that the retreat was not in an easterly direction as expected by the French, but in a northerly direction towards Wavre, from where the Prussians could either come to Wellington's aid or retreat to the east - a decisive factor for the outcome of the later battle.

On the morning of 17 June, Wellington, having learned of the defeat of the Prussians at the battle of Ligny and their retreat to Wavre, set out from Quatre-Bras at 10 o'clock and took up a position between the little town of Braine-l'Alleud and the Meierhof Papelotte. By the morning of June 18 he had drawn up his main force in two divisions on either side of the Charleroi-Brussels road, on a ridge running from west to east. In front of the front of the right wing was the castle of Hougoumont, in the centre the fortified farm of La Haye Sainte, in front of the extreme left wing the farmsteads of Papelotte, La Haye and Fichermont.

Wellington, after the unfortunate outcome of the battle of Ligny, had to expect to be attacked by Napoleon's main force, and therefore confined himself entirely to defence until the arrival of the Prussians. Napoleon had carefully considered the position of his enemy, and had not allowed the troops to set out from their night camps until about 10 o'clock in the forenoon. He placed them about 2 km from the enemy in battle order, so that the infantry formed two meetings, the cavalry a third.

See also: List of French troops of the Armée du Nord

The Lion's Mound and the Rotunda of the Panorama of the Battle of Waterloo

Michel Ney, painting by François Gérard (c. 1805)

The road to Waterloo

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) , painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence (c. 1815)

Consequences and evaluation

It is hardly possible to reconstruct the exact course of events in their temporal context. This was already clear to Wellington when he wrote to his friend John Wilson Croker:

"The history of a battle, is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance. “

- Wellington

Napoleon

"Bonaparte, as well as his advocates among writers, have always endeavored to regard the great catastrophes which have befallen him as works of chance, and to make the reader believe that by the highest wisdom of all combinations, and by the rarest energy, the work had been carried on with the greatest certainty to such an extent that only a hair's breadth was lacking in the most perfect success, that then treachery, chance, or probably fate, as they sometimes call it, spoiled everything. He and they will not admit that great mistakes, great recklessness, and, above all, an overstepping and overbearing of all natural conditions, have been the cause of it."

- Carl von Clausewitz

Wellington

"Wellington's position, according to the testimony of all the witnesses, was very advantageous. As to what was said of the danger which the wood of Soigne, lying close in the rear, should give, it would be necessary to have examined the state of the byways in order to form a judgment. [...] A chief merit in the Duke's measures is the numerous reserves, or, in other words, the small extent of the position for the strength of the army, which left plenty of troops for reserve. Something more could have been done for the establishment and fortification of the three points advanced."

- Carl von Clausewitz

Blücher

"Of Blücher's merit in this victory it is not necessary to say much; it lies chiefly in the resolution to march; we have spoken of that, as well as of the simplicity and expediency of the execution. But a special and very great merit lies in the restless pursuit all night long. It is not at all possible to calculate in what degree this has contributed to the greater dispersion of the enemy's army, and to the greatness and splendour of the trophies which glorify that battle."

- Carl von Clausewitz

The immediate results of the battle were significant. The entire artillery park, the guns and the field equipage of the Emperor fell into the hands of the victors. The French, with all the dead, wounded, and prisoners, lost more than half the army, besides 182 guns. The loss on the part of the allies was 1,120 officers and 20,877 men. On St Helena, Napoleon later blamed the seemingly haphazard advance of the reserve cavalry and the failure of Marshal Grouchy to meet his defeat. Grouchy later claimed to have received the order given by Napoleon on the morning of 18 June only after 7 p.m.; however, his generals Girard and Vandamme contradicted this, and Soult also acknowledged having sent more than one courier at Napoleon's request.

Regarding the seemingly "arbitrary" advance of the cavalry from about 4 p.m. onwards, historians note: Even if the first attack was not directly ordered by Napoleon, he subsequently did nothing to either sufficiently support these cavalry attacks with infantry (Guards) or to break off the attack, which after all took place over a period of about two hours and ultimately comprised about 9,000 horsemen. On the contrary, it is considered certain (Houssaye, 1815) that Napoleon personally ordered the brigade Kellermann, which had initially been held back, to ride up and support the general cavalry attack, which from today's perspective was also militarily senseless and sufficiently invalidates later counter-arguments and cover-up attempts regarding Napoleon's personal "uninvolvement".

On the question of Grouchy, it is usually commented that Grouchy could only have been of use if he had received the orders early on June 18, since the distance to be covered by his troops from Gembloux to the battlefield was far longer than the route taken by the Prussians from Wavre. For a timely intervention, appropriate messages and orders should have been sent to Grouchy as early as night on June 17.

There is no doubt, however, about the fact that Napoleon did not realize the seriousness of his situation until about 1:30 p.m. on June 18, and he also initially assumed that he could deal with Bulow's corps. He did not know that von Zieten was on the march to support Wellington's wavering left flank. Nor did Napoleon suspect that eventually General von Pirch's brigades, marching up behind Bulow, would take Plancenoit in flanking and soon break the French's direct line of retreat. Then, when the first volleys of Prussian twelve-pounders came down on the Charleroi-Brussels road at about 6:30 p.m., Napoleon's flawed strategy was evident.

Napoleon himself had on that day lost his usual firm and cold-blooded attitude, and by his last desperate attack had become militarily responsible for the destruction of his army, and with it the loss of his hundred days' rule. From a historical point of view, three mistakes Napoleon made before the battle are usually mentioned:

- On the morning of 17 June Napoleon could have crushed Wellington with his superior numbers of infantry and especially artillery, while the Prussians were still in retreat after Ligny. Instead, he visited wounded men that morning. He also failed to give Ney the immediate order to attack.

- His second mistake was that he underestimated the tactical skill of Wellington and the cold-bloodedness of the British.

- The third fault was his overconfidence. According to the information given by his brother Jérôme, who had learned of the Prussians' plans from a waiter at the Roi d'Espagne inn, he should have ordered Grouchy to Wavre at once. In that case, only v. Bulow's corps would have succeeded in appearing on the battlefield. Napoleon believed that after the battle of Ligny the Prussians would not succeed in recovering quickly from the battle and attacking again.

Hans Ernst Karl von Zieten, oil painting by Franz Krüger (o. J.)

Questions and Answers

Q: Who fought in the Battle of Waterloo?

A: The French army fought against the British and Prussian armies.

Q: Who was crowned as Emperor of France in 1804?

A: Napoleon was crowned as Emperor of France in 1804.

Q: What did Napoleon launch after he became the Emperor of France?

A: After becoming Emperor of France, Napoleon launched the successful Napoleonic Wars.

Q: How far did France's empire stretch after Napoleon's successful wars?

A: France's empire stretched from Spain to the Russian border after Napoleon's successful wars.

Q: What happened to Napoleon in 1814 after being defeated?

A: After being defeated in 1814, Napoleon accepted exile on the island of Elba.

Q: When did Napoleon take control of the French Army again?

A: Napoleon took control of the French Army again in February 1815.

Q: Where did Napoleon attack his enemies and suffer a defeat?

A: Napoleon attacked his enemies in Belgium and was defeated at Waterloo, which was the last battle of the Napoleonic Wars.

Search within the encyclopedia