Battle of Verdun

![]()

This article is about the 1916 World War I battle. For other meanings, see Siege of Verdun.

Battle of Verdun

Part of: World War I

Map of the battle situation on

February 21, 1916

The Battle of Verdun [vɛrˈdɛ̃] was one of the longest and most costly battles of World War I on the Western Front between Germany and France. It began on February 21, 1916, with an attack by German troops on the stronghold of Verdun, and ended on December 19, 1916, without success for the Germans.

After the Battle of Marne and the protracted war of position, the German Supreme Army Command (OHL) had realized that, in view of the looming quantitative superiority of the Entente, the possibility of strategic initiative was gradually slipping away. The idea of an attack at Verdun originally came from Crown Prince Wilhelm, commander in chief of the 5th Army, with Konstantin Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, chief of staff of the 5th Army, as the de facto leader. The German army command decided to attack what had originally been France's strongest fortress (partially disarmed since 1915) in order to, in turn, get the war on the Western Front moving again. Around Verdun, moreover, there was an indentation in the front between the frontal arc of St. Mihiel to the east and Varennes to the west, threatening the flanks of the German front there. Contrary to subsequent accounts by the German Army Chief of Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, the original intent of the attack was not to "bleed" the French Army without spatial objectives. Falkenhayn, with this assertion made in 1920, attempted to retroactively give ostensible meaning to the failed attack and the negative German myth of the "blood mill."

Among other things, the attack was intended to persuade the British Expeditionary Corps, which was fighting on French soil, to abandon its alliance obligations. The fortress of Verdun was chosen as the target of the offensive. The city had a long history as a bulwark and therefore had great symbolic significance, especially for the French population. Its military strategic value was less significant. In the first period of the war, Verdun was considered a subordinate French fortress.

The OHL planned to attack the frontal arc that ran around the city of Verdun and the belt of forts in front of it. Capture of the city itself was not the primary objective of the operation, but rather the heights of the east bank of the Meuse River in order to put its own artillery in a commanding position, analogous to the siege of Port Arthur, and thus make Verdun untenable. Falkenhayn believed that France could be induced, for reasons of national prestige, to accept unjustifiable losses in defense of Verdun. In order to hold Verdun, if the plan had succeeded, it would have been necessary to recapture the heights then occupied by German artillery, which was considered virtually impossible in light of the experience of the battles in 1915. The action bore the code name Operation Gericht. The High Command of the 5th Army was charged with its execution.

The battle marked a high point in the great material battles of World War I - never before had the industrialization of war been so evident. Here, the French system of noria (also called "paternosters") ensured a regular exchange of troops according to a rotation principle. This contributed significantly to the defensive success and was a major factor in establishing Verdun as a symbolic place of remembrance for all of France. The German leadership, on the other hand, assumed that the French side was forced to replace troops because of excessive losses. In the German culture of remembrance, Verdun became a term associated with a sense of bitterness and the impression of having been burned.

Although the Battle of the Somme, which began in July 1916, involved significantly higher casualties, the months of fighting before Verdun became a Franco-German symbol of the tragic lack of results in the war of position. Today, Verdun is considered a memorial against acts of war and serves as a common memory and before the world as a sign of Franco-German reconciliation.

The German attack began on February 21, 1916, after the actual attack date of February 12 had been postponed several times because of freezing and wet weather, but this delay in the attack between February 12 and 21, as well as reports of defections, gave French reconnaissance the time and the arguments to convince Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre that a large-scale attack was being prepared. Hastily, on the basis of irrefutable evidence of German concentrations on the front, Joffre drew up fresh troops to support the defending French 2e armée. For their part, on the threatened east bank of the Meuse River, the French concentrated some 200,000 defenders facing a German superiority of some 500,000 troops of the 5th Army.

At first, the attack made visible progress. As early as February 25, German troops succeeded in capturing Fort Douaumont in a hand-to-hand coup. As expected from the German side, the commander-in-chief of the 2e armée Philippe Pétain made every effort to defend Verdun. The village of Douaumont was captured only after a hard fight on March 4. To escape the flanking fire, the attack was now extended to the left bank of the Meuse. The heights "Toter Mann" changed hands several times under heaviest losses. On the right bank, Fort Vaux was long fought over and defended to the last drop of water. On June 7, the fort surrendered.

As a result of the Brussilov offensive launched on the Eastern Front in early June, German troops had to be withdrawn from the combat zone. Nevertheless, another major offensive started on June 22. The Ouvrage de Thiaumont and the village of Fleury could be taken. The Battle of the Somme, launched by the British on July 1, resulted in the withdrawal of more German troops from Verdun as planned. Nevertheless, German troops launched a final major offensive on July 11 that took them to just outside Fort Souville. The attack then collapsed due to the French counterattack. Following this, there were only minor ventures on the part of the Germans, such as the attack by Hessian troops on the Souville Nose on August 1, 1916. After a period of relative calm, Fort Douaumont fell back to France on October 24, and Fort Vaux had to be evacuated on November 2. The French offensive continued until December 20, when it too was called off.

Fort Douaumont end 1916

Fort Douaumont beginning 1916

.jpg)

General Philippe Pétain

Previous story

A few months after the outbreak of World War I, the front solidified in western Belgium and northern France in November 1914. Both warring parties built a complex system of trenches that stretched from the North Sea coast to Switzerland. The massive use of machine guns, heavy ordnance, and extensive barbed wire obstacles favored defensive warfare, resulting in the loss-making failure of all offensives without the attackers being able to make any significant terrain gains. In February 1915, the Allies tried for the first time to destroy the enemy positions with gunfire that lasted for hours in order to achieve a breakthrough. However, the German opponents were warned of an imminent attack by the drumfire and made reserves available. In addition, the exploded shells created numerous shell funnels, which hampered the advance of the attacking soldiers. The Allied offensives in Champagne and Artois therefore had to be abandoned due to high casualties.

The German strategy - "Operation Court

In the winter of 1915, the Supreme Army Command (OHL) under Erich von Falkenhayn began planning an offensive for the coming year. All strategically possible and promising front sections were discussed. The OHL came to the conclusion that Great Britain had to be driven out of the war, since its exposed maritime position and its industrial capability made it the engine of the Entente. Based on these considerations, Italy was discarded as an unimportant target for attack. Likewise Russia: although German and Austro-Hungarian forces had made major territorial gains in the July-September 1915 campaign against Russia, Falkenhayn was convinced that German forces were insufficient for a decisive advance because of the vast size of the Russian Tsarist Empire. Even the capture of St. Petersburg would be only symbolic in nature and would not bring a decision due to a retreat of the Russian army into the area. Ukraine would be a welcome fruit of such a strategy because of its agriculture, but it was likely to be plucked only with the unequivocal consent of Romania, since the latter's entry into the war alongside the Entente was to be prevented. Other theaters in the Middle East or Greece were designated as irrelevant. This left an attack on the Western Front as the only option. In the meantime, however, the British positions in Flanders had been built up to such an extent that Falkenhayn proposed the French front as the decisive theater of war.

He argued: "France [has] come close to the limit of what is still tolerable in her achievements - by the way, with admirable sacrifice. If it succeeds in making clear to its people that they have nothing more to hope for militarily, then the limit will be crossed, England will have her best sword knocked out of her hand." Falkenhayn hoped that the collapse of French resistance would be followed by the withdrawal of British forces.

He considered the strongholds of Belfort and Verdun as targets for attack. Due to the strategically rather insignificant location of Belfort near the German-French border and the possible flanking of the fortress of Metz, the Supreme Army Command decided in favor of the fortress of Verdun.

At first glance, Verdun's strategic position in the frontal belt promised a worthwhile target: after the border battles in September 1914, the German offensive had formed a wedge in the front at Saint-Mihiel, which hung as a constant threat in front of the French defenders. This allowed the German 5th Army under Crown Prince William of Prussia to attack from three sides, while the French High Command (GQG - Grand Quartier Général) was forced to withdraw troops from other important sections of the front and move them to the attacked section via the narrow corridor between Bar-le-Duc and Verdun. On the other hand, a look at the geography gives a completely different picture: the French fortifications had been dug into the slopes, forests and peaks of the Côtes Lorraines. The forts, fortified dugouts, walkways, concrete blockhouses and infantry works were almost impossible obstacles for the attacking soldiers to take; barbed wire, brush, undergrowth and the difference in altitude of up to 100 meters to overcome also hindered the attackers. One had to reckon with great losses.

To counter these conditions, the attack of the German units was to be prepared with a gunfire of previously unknown extent. The strategic plan was given the name "Chi 45" - the name for "court" according to the secret key in force at the time. At Christmas 1915, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave permission for the offensive to be carried out. The actual attack was to be led by the German 5th Army under Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia on the east bank of the Meuse. A large-scale attack on both sides of the river was ruled out by Falkenhayn. This apparently counter-intuitive decision, which failed to take into account the superior position of the Germans on both sides of the river, was sharply criticized by both Crown Prince Wilhelm and Konstantin Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, Chief of Staff of the 5th Army and the actual decision-maker. Nevertheless, no modifications were made to "Chi 45".

Falkenhayn's goals

While the capture of the city by German troops would have had a negative impact on French war morale, Verdun could not have been used as a launching point for a decisive attack on France. The distance to the French capital Paris is 262 kilometers, which would have been almost insurmountable in such a war of position.

In his memoirs on his time in the OHL, published after the war (1920), Falkenhayn claims that as early as 1915 he had spoken of a strategy of attrition, a tactic of "tear out and hold." The fact that Falkenhayn had not launched a concentrated attack on either bank of the Meuse River, which might have meant the rapid capture of Verdun, is often cited in support of this statement. One interpretation of this decision was that the OHL thereby wanted to avoid direct success, thus concentrating French troops in front of Verdun for defense. In this respect, therefore, Falkenhayn would actually have intended not the capture of Verdun but the involvement of the French army in a protracted battle of attrition that would eventually lead to the complete exhaustion of France in material and personnel. This plan, however, cannot be proved by any records except those written by Falkenhayn himself and much later, and is today regarded skeptically but not as impossible. In fact, Falkenhayn believed in a counterattack on the flank and wanted to hold back appropriate reserves so that he could not provide enough troops for a simultaneous attack on both banks of the Meuse. Falkenhayn by no means wanted to avoid a direct success.

It is more likely, and therefore a common reading, that Falkenhayn, as head of the army a rather hesitant strategist, did not pursue this strategy from the beginning, but only declared it to be a means to an end in the course of the battle; this mainly as a justification against the background of the unsuccessful advances and the high own losses. This interpretation is clearly supported by the orders given to the fighting troops, which were designed to gain ground: Falkenhayn ordered an offensive "in the area of the Meuse in the direction of Verdun," the crown prince declared to "quickly bring down the fortress of Verdun," and von Knobelsdorf had given the two attacking corps the task of "advancing as far as possible." The attacking 5th Army put these orders into action without tactically waiting, following the bleeding-out strategy, and without attacking exclusively for high foreign casualties. The primary objective of the attack was to conquer the high ground on the east bank of the Meuse River in order to bring its own artillery into a commanding position there.

The fortress of Verdun

→ Main article: Verdun Fixed Square

From the French point of view, defending Verdun was a patriotic duty, but one that completely contradicted the modern military view: a strategic retreat to the wooded ridges west of Verdun would have created a much easier defensive position, erased the bulge, and freed up troops. But the French military doctrine of 1910, vehemently advocated by Joffre, was the offensive à outrance (roughly, 'to the extreme'). Defensive tactics or strategy were never seriously considered. When some officers, including General Pétain and Colonel Driant, expressed misgivings about this doctrine, their stance was rejected as defeatist.

Driant, as commander of the important section in Caures Forest and commander of the 56th and 59th Battalions of Chasseurs à pied, had tried several times in vain to persuade the GQG to make significant improvements in the French trench system. On his own, Driant had his fighters fortify their position against the expected attack; nevertheless, Driant fell in the first assault on 22 February. Complementary to a sensible defense, the GQG and Joffre relied on the system of French defense by attack, the backbone of which was the thrust of the poilu, the common soldier whose cran, his courage, would give him the decisive advantage.

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, France proceeded to secure the border with the German Empire by building fortifications (barrière de fer) that were contemporary at the time, despite the conviction that victory could only be achieved by an infantry advance. To this end, several eastern French cities were surrounded with a ring of forts, including Verdun, located on the Meuse River. Verdun was seen primarily as a replacement for the lost Metz, whose old fortifications had been greatly expanded by the Empire. At the beginning of the war, there were over 40 fortifications in and around Verdun, including 20 forts and intermediate works (ouvrages) equipped with machine guns, armored observation and gun turrets, and casemates. Verdun was thus one of the best fortified sites. Another reason for the particularly strong development of the Verdun fortress was the short distance of 250 km to Paris, even for the means of transport of the time, as well as its location on a main road.

Already from September 22 to 25, 1914, there had been fighting in front of Verdun, which had ended the German advance in the Meuse region. Under the impression of the enormous destructive power of the German siege guns before Namur and before Liège, the importance of strong fortifications in an attack with heavy siege guns (for example 30.5-cm siege mortars) was seen differently than before.

Also, the siege of Maubeuge (it began on August 28, 1914 and officially ended on September 8, 1914 with the surrender of Maubeuge) - had shown Germans and French that fortresses were not impregnable but could be 'shot up'.

This, together with the fact that the warring parties concentrated on other sections of the front in the aftermath of the border battles, led to a lesser military importance of Verdun after a reassessment: the GQG under Joffre declared Verdun a quiet section. On August 5, 1915, the fortress of Verdun was even officially downgraded to the center of the Région fortifiée de Verdun - RFV ("Fortified Region of Verdun"). In the months that followed, 43 heavy and 11 light gun batteries were consequently withdrawn from the fortified ring and most of the forts' machine guns were transferred to field units. Only three divisions of the XX Corps were now stationed there:

- the 72nd Reserve Division from the Verdun region,

- the 51st Reserve Division from Lille and

- the 14th regular division from Besançon.

The 37th Division from Algeria was in reserve.

Verdun until the end of the war

In 1917, the warring parties concentrated on other sections of the front, but there were still several battles in front of Verdun, even if they did not take on the same proportions as in the previous year. In particular, Hill 304 and the "Dead Man" were again fiercely fought over from June 1917 onwards. By June 29, German units succeeded in completely occupying Hill 304. In August, French attacks led to the final evacuation of Hill 304 and the "Dead Man" by the Germans. Further action followed on the right bank of the Meuse in the area of the village of Ornes and Height 344, but the Meuse area was not to become the scene of major attacks again until the end of the war. An advance by American troops under General Pershing pushed in the German front southeast of Verdun by several kilometers on August 30, 1918. This was followed on September 26 by the Franco-American Meuse-Argonne offensive, which started from Verdun and drove the Germans back from the Argonne by early November. On November 11, the armistice came into effect.

The "Hell of Verdun

Due to the massive use of guns (explosion craters) in a confined space, the battlefield at Verdun had been transformed within a few weeks into a cratered landscape (see zone rouge), in which often only tree stumps remained of the forests. At times, more than 4,000 guns were used in the comparatively small combat area. An average of 10,000 shells and mines fell every hour in front of Verdun, creating a deafening background noise. When they exploded, they hurled up large quantities of earth, burying numerous soldiers alive. Not all of them could be freed from the earth in time.

Due to the omnipresent fire from guns and machine guns, many dead and wounded had to be left in no man's land between the fronts, which is why a heavy stench of corpses hung over the battlefield, especially in the summer months. Moreover, in the permanent hail of bullets, it was often impossible to supply the front-line soldiers with sufficient supplies or to relieve them. Already on the way to the front line, numerous units lost far more than half of their men. Hardly a soldier who was deployed before Verdun survived the battle without being at least slightly wounded.

The soldiers often had to wear their gas masks for hours and go without food for several days. Thirst drove many of them to drink contaminated rainwater from shell crushers or their urine. Both French and German soldiers dreaded front-line action at Verdun. They referred to the battlefield as the "blood pump," the "bone mill," or simply "hell." When it rained, the battlefield resembled a muddy field, making any troop movement very difficult. Every path was dug in, the whole area was a single funnel field. Increasingly strong horse teams had to be used to move a single gun. These teams suffered particularly heavy losses under fire: up to 7000 military horses are said to have perished in a single day. Of particular importance were the forts in front of Verdun, which offered protection to the troops and were used for the first aid of the wounded, but the hygienic conditions there were catastrophic. The military leaders on both sides were well aware of what the soldiers had to endure in battle, but they did not draw any conclusions from this.

Even 100 years after the battle, the explosion craters are still clearly visible, as here at Bezonvaux

Verdun as myth

Legends and myths

Fleury and Thiaumont

Especially the merciless struggle for Fleury and Thiaumont was often transfigured and distorted. The change of possession of these places was often taken as an occasion to illustrate the senselessness of the war. Sometimes exaggerated numbers are mentioned here; there are reports of 13, 23 or even 42 exchanges between Germans and French. Officially, the village of Fleury and the intermediate works of Thiaumont changed hands four times each between June and October. The following attacks and counterattacks are attested:

Fleury was partially captured on June 23, it was completely in German hands on July 11, and on August 2, French troops were pinned down in Fleury for a day, after which the Germans held it until August 18. From that day on, the positions were located at the notorious Fleury railroad embankment. On October 23, the Germans had to completely clear the area.

Similarly for Thiaumont: capture by the Germans on June 23, loss on July 5, recapture on July 8, and final loss on October 23 as a result of the major French offensive.

The bayonet trench

→ Main article: Tranchée des Baïonnettes

After the war, east of a small ravine at Thiaumont called Ravin de la Dame, "Bois Hassoule" (Hassoule Ravine) or also "Ravin de la Mort" (Dead Man's Ravine), a trench was discovered from which the tips of the soldiers' mounted bayonets protruded. Investigations revealed that the soldiers were indeed still in contact with their rifles. In the 1930s, the legend arose that these soldiers of the French 137th Infantry Regiment had been buried alive and standing by a shell during attack preparations on the Thiaumont intermediate works.

The testimony of a lieutenant of the 3rd Company, to which the soldiers belonged, presented a completely different picture: "The soldiers had fallen during a German advance on the morning of June 13, 1916, and were left in their trench. The Germans buried them (they filled in the trench) and their (upright) rifles served as markers for the grave site." An exhumation in 1920 confirmed his explanation: none of the seven bodies stood upright, and four could not be identified. Today the site can be seen in the monument La Tranchée des Baïonnettes, built by an American industrialist.

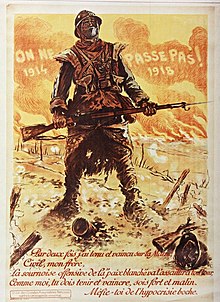

Ils ne passeront pas!

→ Main article: Ils ne passeront pas!

"Ils ne passeront pas! " ("They won't get through!"), also "On ne passe pas! ", was the central propaganda slogan of the Verdun myth. It was coined by the French generals Nivelle and Pétain. It was later used in many propaganda posters as well as a slogan for the Maginot Line. The slogan was also used frequently later on. One of the most exploitative examples was shortly after the start of the SpanishCivil War when Republican Dolores Ibárruri used the Spanish version of the slogan, "¡No pasarán!" in a speech. Today, the Spanish version of the slogan is a symbol of the political left.

The view of the city of Verdun

Among others, in the book "Verdun - Das große Gericht" by P. C. Ettighoffer it is mentioned that the Germans, after their major attack of June 23, 1916, during which also the ammunition rooms near Fleury (Poudriere de Fleury) were taken by the Bavarian Infantry Leibregiment, could have seen Verdun from the so-called. "Filzlausstellung" (Ouvrage de Morpion) he could see the city of Verdun. Ettighoffer further writes that soldiers of the Leibregiment brought machine guns into position and shelled Verdun from the "Filzlaus". This is impossible, because in the case of the "Filzlausstellung" the view is blocked by the Belleville ridge, which can be seen by a simple look at a map. Further, this shelling of the town is not mentioned in any other source. Not even the regimental history of the Infantry Leibregiment mentions such a bombardment, although this would be more than worth mentioning. There it is only stated that a small assault party of the 11th Company probed as far as the "felt exhibition" and immediately afterwards returned to the ammunition rooms with some French prisoners. To this day it is unclear how Ettighoffer arrived at this assertion, since Verdun is not visible from any point on the battlefield that German soldiers had ever reached.

Verdun from the French point of view

Verdun had a unifying function for the French people, which became a national symbol against the background of the struggle defined as a defense. The First World War ultimately became a just war against the aggressor only through the resistance before Verdun, which was celebrated as a victory, even if France's war strategy before the start of the war in 1914 was anything but passive.

In the post-war years, the defense of Verdun was increasingly glorified as a heroic deed. The fortress of Verdun was seen as an insurmountable bulwark that had guaranteed the survival of the French nation. For the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, the body of a Frenchman who had fallen before Verdun was exhumed. General Pétain was declared a national hero by the French and was appointed Marshal of France in 1918. In his honor, a statue was erected on the battlefield in front of Verdun after the war, on whose pedestal a modification of the central phrase of the French Verdun myth can be read: "Ils ne sont pas passés" ("They didn't get through").

The glorification of the Battle of Verdun as a successful assertion of an impregnable fortress was to have disastrous consequences for France in 1940, as it was no match for modern warfare with rapid advances by armored units - as practiced by the Wehrmacht in the Western campaign (May 10-June 25, 1940). Pétain was sentenced to death for his cooperation with the Third Reich in August 1945; probably because of his merits in the Battle of Verdun, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

On the battlefields even today this more or less national significance of the battle is omnipresent. At Fort Douaumont, the tricolor, the German flag and the European flag have been flying for many years. At many other sites of the battle, which have been incorporated into the collective memory, the tricolor flies to emphasize the national significance. The same interpretation applies to the various monuments around Verdun (Monument of the Armed Forces, Lion of Souville (it represents a dying Bavarian lion and marks the furthest advance of the German troops), Maginot Monument, ...), which all celebrate the national idea and supposed victory, but very rarely commemorate the death of the soldiers.

It was not until the joint confession by François Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl on September 22, 1984 that this strongly national symbolism was broken in order to commemorate a common past together with Germany.

Verdun from the German point of view

Since the offensive on the Meuse had led neither to the capture of Verdun nor to the complete attrition of the French army, essential offensive objectives had not been achieved. Like most other battles, the fight before Verdun was not seen as a real defeat of the German army after the lost world war. This was mainly supported by the stab-in-the-back legend spread by national forces in Germany. Verdun was seen as a beacon for an entire generation - similar to the sacrifice of school leavers and students in 1914 in the First Battle of Flanders. Until the takeover of power in 1933, however, Verdun was seen from a much less heroic perspective, since the senselessness of the ten-month battle could hardly be interpreted otherwise.

Most of the German war novels published during the Weimar Republic were about the Battle of Verdun. "Verdun" became the symbol of modern, fully industrialized war. It was no longer a question of victory or defeat, but of the experience of the material battle. Even the question of the meaning of the bloody positional battles was considered secondary in view of the enormous destructive power of modern war equipment. The German Verdun myth centered not on critical hindsight, but on the experience of the battle. A central role was played by the Verdun fighter, who was seen as a new type of soldier. This was described as characterless, cold and hard and displaced earlier, romantically transfigured ideal images, as they prevailed especially in the bourgeois milieu. In the Third Reich, this myth was further expanded. The fact that many officers of World War II had served before Verdun led to its instrumentalization for propaganda purposes.

After 1945 and under the impression of the Second World War, which was even more devastating for Germany, the Battle of Verdun was rarely addressed in the Federal Republic and then generally interpreted in a sober manner.

Result of the battle - a German success?

Depending on one's perspective, the outcome of the fighting before Verdun is interpreted differently, as a French success, a draw, or a German success.

A simple and easily ascertainable yardstick is the position of the front line on February 24, 1916. Weighing the advance and the terrain gained by the Germans can lead to the interpretation that even after the battle ended in December 1916, the German army held more terrain gained than it had lost through the French counterattack beginning in July 1916, and to that extent it could be seen as the winner of the actual Battle of Verdun. This front was largely held until the arrival of the Americans and the loss of the St. Mihiel Arc. However, since this increase in held terrain had no significant strategic impact on the course of the war, this choice of scale is questionable as a resilient criterion.

Another possibility is to compare the outcome of the battle with the original objectives: According to this assessment, the Battle of Verdun was a major failure for the German side, as its objectives were missed and instead German offensive power was decisively weakened.

The trenches today

French propaganda poster with the slogan " On ne passe pas! “

Bayonet trench in 2006

Verdun Victory Monument

The battlefield today

On the disputed territory exploded about 50 million artillery shells and throwing mines. The landscape was plowed through several times, from which it has not fully recovered to this day. There are still numerous unexploded ordnance, rifles, helmets, pieces of equipment and human bones in the soil of the battlefield. The formerly embattled forts and intermediate works, such as Douaumont and Vaux, were badly damaged but can be visited. There are numerous cemeteries and ossuaries around Verdun. The Douaumont Ossuary contains the bones of some 130,000 unidentified German and French soldiers. Near Fleury is the Mémorial de Verdun, a museum displaying war equipment used at the time, weapons, uniforms, ground finds, photographs, etc. It is also possible to attend a film screening.

Monuments and tours

- Fort de Douaumont

- Fort de Vaux

- Fort de Souville

- Fleury-devant-Douaumont

- Height 304

- Mort-Homme (Dead Man)

- Tunnel de Tavannes

- Bois des Caures (Lt. Col. Driant's command bunker, grave and monument)

- The Voie Sacrée

- The Tranchée des Baïonnettes

- The Ouvrage de Thiaumont and Ouvrage de Froideterre

- The destroyed villages of Vaux, Bezonvaux, Ornes, Haumont, Louvemont and Beaumont

- The monument to the fallen Frenchmen of Muslim faith (inaugurated in 2006).

- The Citadelle de Verdun, located in the city, under the cathedral

- Military cemetery Hautecourt

- War cemetery Metz: Deceased severely wounded of the military hospital in Metz

as well as several dozen other bunkers, intermediate works, batteries, memorials, monuments, and individual graves scattered throughout the battlefield.

Museums

- The Mémorial de Verdun

- L'ossuaire de Douaumont - The Bone House

- The Forts de Vaux and Douaumont

- Centre mondial de la paix - The World Peace Center in the Episcopal Palace of Verdun

- The museum "De la Princerie" in the city center

Also

- The cathedral of Verdun

- The old city gate "Porte Chaussee

Fort de Douaumont

The remains of the Thiaumont intermediate plant

Shell funnel on a former battlefield

Movies

- The Hell of Verdun. Scenic documentary, 90 min. Production: ZDF, Director: Stefan Brauburger and Oliver Halmburger, Script: Thomas Staehler, First broadcast: August 30, 2006 (ZDF synopsis).

- Along the Sacred Road in Lorraine. Between Verdun and Bar-le-Duc. (=episode from the cinematic travel guide series Fahr mal hin). D 2011, 30 min., written and directed by Maria C. Schmitt, produced by SWR, (SWR synopsis).

- On the Sacred Road through Lorraine. 100 years after the First World War. D 2014, 45 min., Written and directed by Maria C. Schmitt, produced by SR.

- Apocalypse Verdun (original title: Apocalypse: Verdun). F 2015, documentary, 90 min, directed by Isabelle Clarke and Daniel Costelle (first broadcast as a two-parter on ZDFinfo in 2016).

- The Century of Verdun (Original title: Le siècle de Verdun). F 2006, documentary, 56 min, directed by Patrick Barberis and Antoine Prost.

- Alptraum Verdun (=Part 3 of the documentary series: The First World War). D 2004, documentary, written and directed by Mathias Haentjes and Werner Biermann.

- Verdun - They will not get through! (Original title: Ils ne passeront pas). F 2014, 82 min, documentary, directed by Serge de Sampigny.

Search within the encyclopedia