Battle of the Plains of Abraham

Battle on the Abraham Plain

Part of: Seven Years War in North America

The death of General Wolfe

Painting by Benjamin West, oil on canvas, 1770

Seven Years' War (1756-1763)

European theater of war:

Pirna* - Lobositz* - Prague* - Kolin* - Hastenbeck** - Groß-Jägersdorf* - Moys* - Hastenbeck* - Roßbach* - Breslau* - Leuthen* - Rheinberg** - Krefeld** - Domstadtl* - Olmütz* - Mehr** - Zorndorf* - Saint-Cast - Hochkirch* - Bergen** - Kay* - Minden** - Kunersdorf* - Lagos*** - Hoyerswerda* - Bay of Quiberon*** - Maxen* - Koßdorf* - Landeshut* - Emsdorf** - Warburg** - Liegnitz* - Berlin* - Kloster Kampen** - Torgau* - Döbeln* - Vellinghausen** - Ölper** - Burkersdorf* - Reichenbach* - Freiberg*

(* Third Silesian War, ** Western theater of war - Great Britain/Kur-Hannover a. o. Allies against France, *** Naval battle)

American theater of war:

Seven Years War in North America

Monongahela - Carillon - La Belle Famille - Québec - Beauport - Abraham Plain - Sainte-Foy - Restigouche

Asian theater of war:

Third Carnatic War

Cuddalore - Negapatam - Pondicherry - Wandiwash - Manila

The Battle of Abraham Plain was a battle of the Seven Years' War, also known in the North American theater as the French and Indian War. It took place on September 13, 1759, near Quebec City in what is now Canada. British and French troops faced off on the Plains of Abraham, a high plateau immediately southwest of the city walls of Québec. Although less than 10,000 men in total were involved in the battle, it proved to be a decisive event in the conflict over the rule of New France and later had an impact on the formation of Canada.

The actual battle lasted only about 15 minutes, but was the climax of the two-and-a-half-month siege of Quebec by the British army and navy. The British, under the command of General James Wolfe, successfully resisted a sally of French troops and Canadian militia under General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm. They employed new tactics that proved markedly effective against standard military formations used in most major European conflicts. Both generals were mortally wounded during the battle. Wolfe was hit by three rifle bullets and died a few minutes after the battle began; Montcalm succumbed a day later to injuries he had received from a musket ball.

As a result of the battle, the French abandoned the city and their remaining troops in North America came under increasing pressure from the British. Although the French continued to fight after the capture of Québec and maintained the upper hand in some engagements, the British did not surrender the strategically important city. With the Peace of Paris in 1763, most French territories in eastern North America passed into British possession.

Siege

→ Main article: Siege of Québec

By 1758, the British had captured Fort Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley, and Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario. The French were encircled, but were initially able to halt the outright conquest of New France with victory at the Battle of Fort Carillon. The British blockade of the St. Lawrence River during the winter proved a failure, as numerous French ships managed to deliver supplies to Quebec. In May 1759, the French began to evacuate and entrench the population. On June 26, the British fleet landed in the vicinity of Québec, whereupon the soldiers occupied Île d'Orléans and established the main camp there. A French attack on the fleet with fires failed. The following day, the British also occupied the south bank of the St. Lawrence River and began building artillery batteries.

British artillery fire from the opposite bank began on July 12 and continued unabated for the next two months. The heavy bombardment, which the French had little to counter, took place mainly during the night hours and caused extensive damage to the city. Numerous buildings, including Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral and Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church, fell victim to the flames. On July 31, General James Wolfe attempted the first serious attack on the north shore. The British landed at Beauport but were repulsed by the French. In all, this Battle of Beauport claimed 443 casualties on the British side and 60 casualties on the French side. In retaliation, Wolfe ordered the destruction of all houses in a section several dozen miles long along the south bank of the St. Lawrence River, also northeast of Beauport. While this action was in progress, he drafted and discarded new plans of attack. He had to interrupt his work due to a prolonged period of illness in August.

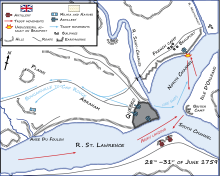

Beginning of the siege at the end of June

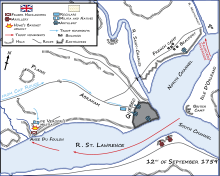

Preparations and landing

In late August, Wolfe and his brigadiers agreed to cross the St. Lawrence River west of the city. Numerous soldiers had already boarded the ships and drifted up and down the river for several days when Wolfe made the final decision on September 12 and his choice of landing site was Anse au Foulon. This small cove is located southwest of town at Sillery, about three kilometers from Cap Diamant. It is located at the foot of a 53-meter-high cliff that merges into the plateau above; it was protected at the time by a battery of cannons. It is not known why Wolfe chose this site, as the landing was originally planned further upstream. There the British could have set up a beachhead and moved against Louis Antoine de Bougainville's troops encamped farther west, thereby luring Louis-Joseph de Montcalm out of the city and onto the high plateau. According to Brigadier George Townshend, the general had changed his mind based on scouting reports. In his last letter, dated September 12 at 8:30 p.m. on HMS Sutherland, Wolfe wrote:

"I had the honor to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French army. To the best of my knowledge and ability, I have fixed upon that spot where we can act with most force and are most likely to succeed. If I am mistaken I am sorry for it and must be answerable to His Majesty and the public for the consequences."

"I had the honor to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French army. To the best of my knowledge and belief, I have chosen that place where we can act with the greatest strength and are most likely to succeed. If I am wrong, I am sorry and will have to answer to His Majesty and the public for the consequences."

Wolfe's plan of attack depended on secrecy and surprise. A small group was to go ashore at night on the north shore, climb the steep slope, occupy a small road and overwhelm the garrison standing guard there. The bulk of the army (5000 men) was to climb the slope via the small road and then form up on the high plateau. Even if the first group succeeded and the army managed to follow it, his troops would be placed inside the French defensive line - with the river as the only means of retreat. It is possible that Wolfe's decision to change the landing site had less to do with a desire for secrecy than with his general disdain for his brigadiers (a feeling that was mutual). He may also still have been suffering from the effects of his illness in the second half of August and the opiates he took as painkillers. Historian Fred Anderson believes Wolfe ordered the attack in the belief that the advance guard would be repulsed and that he expected to die chivalrously with his men rather than return home in disgrace.

Bougainville, charged with defending the extensive plateau, was with his troops farther upriver at Cap Rouge on the evening of September 12 and did not notice the numerous British ships drifting downriver. A group of 100 militiamen under the command of Captain Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor had been ordered to patrol the narrow road at Anse au Foulon, which followed the bank of the Saint-Denis creek. On the night of September 13, there were probably just 40 men at their post, as the others were busy bringing in the harvest. Vaudreuil and others had expressed concern about the possible weak point at Anse au Foulon, but Montcalm dismissed them, saying 100 men were enough to hold off an army until sunrise. He commented, "The enemy cannot be expected to possess wings, so that in the same night he would cross the river, disembark, climb the obstacle-strewn slope, and scale the walls, carrying ladders for the latter."

Guards actually spotted boats on the river, but they were expecting a French supply convoy - a plan that had been cancelled without Vergor being informed. When the first boats landed, the crew was asked to identify themselves. To this, an excellent French-speaking officer of the 78th Fraser Highlanders responded and allayed suspicion. The boats had gone a little off course. Instead of landing at the end of the road, numerous soldiers found themselves at the bottom of a slope. A group of 24 volunteers led by William Howe was sent out to clear the fence along the road and climb the slope. This allowed them to emerge behind Vergor's camp and quickly capture it. Wolfe followed an hour later when he was able to use a convenient access road to get to the plateau. By the time the sun rose over the Abraham Plateau, Wolfe's army had a solid base above the slope.

Drawing of British soldier representing the landing

Landing of the British troops on September 12

Search within the encyclopedia