Syrian civil war

The civil war in Syria has been an armed conflict between various groups since 15 March 2011, and as it progresses it increasingly involves third countries that are also pursuing their own interests. The Syrian armed forces under the command of President Bashar al-Assad are opposed by armed opposition groups. The conflict was triggered by a peaceful protest against Assad's authoritarian regime in the wake of the Arab Spring in early 2011, which saw growing influence from the Muslim Brotherhood, other radical Sunni groups and foreign interests. In addition to the influx of weapons, more and more foreign volunteers and mercenaries were also fighting in Syria. The opposition's desire to achieve the democratization of Syria gradually receded into the background in this war; instead, the struggle of various organizations on religious and ethnic grounds came to the fore.

The country disintegrated into areas dominated either by Assad's government, opposition groups, the Kurdish People's Defense Units, or Islamists. The direct involvement of Assad's allies - Iran with its Revolutionary Guards, the Lebanese Hezbollah militia and Russia with its military deployment - as well as the formation of an international alliance led by the United States against the Sunni terrorist group "Islamic State" (IS) turned the fight within Syria into a regional proxy war: Here, among others, Shiite Iran is fighting against Sunni Saudi Arabia and Qatar, as well as Russia and the USA for supremacy in the region. Turkey, which is pursuing its own interests, particularly with regard to the Kurds there, has also intervened significantly in the conflict since 2016 at the latest with its military offensives in northern Syria.

The United Nations special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, estimated in April 2016 that 400,000 people had been killed since the war began; in April 2018, experts put the figure at 500,000. The 2016 United Nations figures were based in part on 2014 data, and other organizations had abandoned the count. Some 12.9 million Syrians were displaced in 2018, including 6.2 million inside Syria, while 6.7 million people left Syria. In 2021, UNICEF estimated that nearly 500,000 people had been killed.

The UN described the refugee crisis triggered by the war as the worst since the Rwandan genocide in the 1990s. The involvement of several foreign powers is making it difficult to end the civil war.

Status: 13 February 2021

Controlled by Syria's armed forces or other pro-Assad forces![]() .

.

Controlled ![]() by Kurdish forces or the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

by Kurdish forces or the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

![]() Controlled by "Islamic State" (IS)

Controlled by "Islamic State" (IS)

Disputed territory

![]() Controlled by opposition forces or Turkish armed forces

Controlled by opposition forces or Turkish armed forces

![]() Controlled by Haiʾat Tahrir ash-Shame

Controlled by Haiʾat Tahrir ash-Shame

Equal control between government and opposition forces or ceasefire![]()

joint control of government and SDFIn![]() the respective colors:

the respective colors:

![]() Equal control

Equal control

![]() troops in the outskirts of towns or villages

troops in the outskirts of towns or villages

![]() contested

contested

![]() strategic hill

strategic hill

![]() Oil or gas field

Oil or gas field

![]() military base or checkpoint

military base or checkpoint

![]() airport or airbase

airport or airbase

![]() helipad or helicopter base

helipad or helicopter base

![]() important port or naval base

important port or naval base

![]() border post

border post

![]() dam

dam

![]() Industrial complex

Industrial complex

Background

→ Main articles: History of Syria and Political system of Syria

In Syria, the nationalist "Arab Socialist Baath Party" has ruled in the form of one-party rule since a military coup in 1963, and Hafiz al-Assad has ruled as president since the coup d'état of 1970, which was called the "corrective movement". Real opposition parties are not allowed. In 1970, the military wing in the Baath Party seized power. After Hafiz's death in 2000, his son Bashar took power; he initiated a short-lived policy of opening from 2000/2001, the Damascus Spring.

Socio-economic situation

Between the 1960s and 1980s, Syria had one of the highest population growth rates among Middle Eastern and North African states. The peak was reached in the 1970s with an average birth rate of 7.6 children per woman. Combined with a steadily declining death rate over the same period, this led to a population increase from 4.5 to 13.8 million people between 1960 and 1994. Growth has slowed since then. In 2010, about 22.5 million people lived in Syria.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Syrian state was able to support the Syrian economy through investments consisting of economic aid from the Soviet Union, support from other Arab states, transfer fees for Iraqi oil, and profits from a small amount of its own oil production, to such an extent that high economic growth and sufficient jobs were generated. With the removal of foreign support and the collapse of oil prices in the 1980s, population growth significantly outpaced that of the now stagnant economy. The crisis was exacerbated by the Syrian government's large military budget; high unemployment rates and massive inflation were the consequences. One attempt to halt these developments was a halving of the military budget from 1985 to 1995. In 1987, additional support for families with particularly large numbers of children was also halted. The high level of foreign debt to the Soviet Union or its successor, Russia, and various Western industrialized nations, combined with a renewed drop in oil prices in the mid-1990s, dampened economic growth. The liberalization of the economy thus appeared necessary, with the aim of reducing state involvement and promoting the private sector in order to bring as large a proportion as possible of the employable population into paid employment that would not be dependent on permanent subsidies from tight state finances. Such reforms had been recognized early on by the Syrian leadership, and the goal of a stronger private sector was articulated by the sole ruling Baath Party in 1985, but the government's cumbersome, highly centralized administrative system, which after all employed nearly one in three Syrians in paid work, was incapable of implementing such initiatives.

After the death of President Hafiz al-Assad in 2000, his son and successor initially attempted to implement parts of these economic reforms; however, he did not allow any sustainable democratic reforms to the one-party or administrative system, and the economic situation hardly changed. Increased demand from the private sector, generated primarily by refugees from Iraq and investment from the Gulf region from 2004 to 2007, temporarily generated economic growth of 4 %, but this development did not last. While the government reported an unemployment rate of 10 %, other estimates identified much higher figures, ranging up to 50 % for the under-30 age group before the outbreak of the civil war.

Crop failures since 2007 have exacerbated the crisis situation. Rapid population growth increased the demand for water. Many illegal wells were dug, and oversized and water-intensive agricultural projects over-exploited land and reservoirs. In 2006-2010, a pronounced drought was added to the mix - an event that, according to various researchers, global warming has made much more likely. The Syrian government did not adequately alleviate the plight of the affected people. The result was additional unemployment, price increases, food insecurity, and mass exodus of up to 1.5 million people from rural areas. Syria additionally received about 1.2-1.5 million refugees from Iraq between 2003 and 2007, so that in 2010 about 20% of the urban population were refugees.

As early as 2011, Syria was confronted with a sharp rise in prices for everyday products and a significant deterioration in living standards.

Populations

Among the reasons for the formation of various factions in the civil war is the heterogeneity of the Syrian state and society, which provides potential for conflict at several points:

The population of Syria is ethnically composed of Syrian Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians-Aramaeans, Turkmen, Armenians, Circassians and Palestinians. These are distributed among various religious communities, among which the Sunnis are the most numerous, accounting for over 70% of the population. The country's religious minorities include the Shiites (Alawites, Druze), Yazidis and Christians.

The Syrian state saw itself as a secular and secular state, with the ruling Baath Party's program, which was based on nationalism and European socialism, and forbade the open political influence of religious groups. Religiously motivated uprisings, such as that of the Muslim Brotherhood, which wanted to use violence to establish the Sunni denomination as the state religion, were put down with great severity as early as the 1980s, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths, such as in the Hama massacre.

Smaller religious communities in Syria tended to see themselves as supported by the separation of church and state, because this prevented radical elements from the ranks of the Sunnis from exerting political influence. The fear of oppression and persecution by religious fanatics therefore also led to expressions of support from the ranks of the minorities for the government in the civil war.

In its report published on 20 December 2012, the UN Commission on Human Rights, which is responsible for Syria, noted that the conflict is increasingly being conducted along ethno-religious lines. Government forces attacked Sunni civilians, while Islamist insurgents attacked Alawites and other supposedly pro-government minorities such as Catholic and Armenian Orthodox Christians and Druze. Minorities such as the Christians, Kurds and Turkmen have since formed their own militias to protect their areas from attack.

Sunni

The mostly Shafiite Sunnis made up the largest share of Syria's population. They had been underrepresented in many areas of the state apparatus since the founding of the ruling Baath Party. This had attracted many religious minorities who had hoped to improve their social position. After the government turned more towards Iran, Sunni religious groups, with support from Saudi Arabia, used their influence and stylized Shiite influence as a threat to the Sunni faith. Impoverished Sunni rural refugees moved into slums around the major cities, where the thesis of danger to the Sunni faith found particularly large numbers of supporters.

According to Kristin Helberg, the Assad government wants to "punish" the Sunnis, often land refugees in informal settlements and those a haven of resistance. Decree number 10 of April 2018, which required all land to be registered and any unregistered property to fall to the state, allowed the state to make room - presumably for people loyal to the regime, she said. Daniel Steinvorth wrote in the NZZ: "Those who are poor and Sunni potentially stand in the way of the demographic reorganization of the country", relating this to a quote by Assad from the summer of 2017, in which he "good-humouredly" spoke of a "healthier and more homogeneous" society in Syria.

The terrorist organizations Islamic State and Al-Nusra Front are considered Sunni militias. The Free Syrian Army (FSA) is considered a Sunni militia insofar as it is supported by part of Syria's Sunni population.

Alawites

Similar to Iraq, where Saddam Hussein occupied positions of power with representatives of his Tikrit clientele, there is a Qardaha clientele in Syria. Qardaha is a village in northern Syria inhabited predominantly by Alawites of the Matawira tribe, where Hafiz al-Assad, the father of Syria's current president Bashar al-Assad, was born. The Matawira tribe is one of four Alawite tribes. Until now, the Syrian Baath government has secured its stability with the help of the Qardaha clientele in particular. The Alawites (also called "Nusairians") are historically a religious minority that has been repeatedly persecuted for their faith. Since the 19th century, their religious community has been broadly classified as belonging to Ali's party (Shiat Ali) and thus generally to the Shiites. For the orthodox Sunnis, the majority denomination within Syria, the Alawites are considered heretics. In Syria, Alawites make up 12 to 13 percent of the population. Alawites who participate in the uprisings against Assad's government are isolated within their community. As of 2016, at least 70,000 of Syria's 2 million Alawites have died.

Shia

Representatives of Syria's Shiite minority, which after the Alawites counted among the Shiites includes some Twelver Shiites, but above all Mustali and Nizari Ismailis, for the most part see the insurgents not as "freedom fighters" but as "terrorists". In areas that are no longer controlled by the Syrian army, Shiites have to fear for their lives as "infidels". Because of this, they tend to tolerate the brutal crackdown by government forces on insurgents and opposition members and are therefore perceived as supporters of Assad. The same contrast also divides some of Syria's neighbors, which is why there are warnings of regional spillover as the conflict intensifies. In addition to Iraq, Lebanon is usually mentioned here.

Christians

→ Main article: Christianity in Syria

Christianity in Syria has a long history dating back to the conversion of Paul before Damascus. Around 60% of Christians belong to the Syrian Orthodox Church. In November 2011, during a visit of Patriarch Cyril to Damascus, Patriarch Ignatius thanked the Russian Patriarch and all the citizens of Russia for their compassion and support.

In a March 2012 statement, the Syriac Orthodox Church deplored "ethnic cleansing against Christians" in the city of Homs by members of the Faruq Brigades of the Free Syrian Army. Militant armed Islamists had already driven 90% of Christians out of Homs, according to this account. The Faruq Brigades gave an interview to Der Spiegel in April 2012 in which they strongly denied the allegations. Their spokesman Abdel-Razaq Tlas, nephew of former Syrian defense minister Mustafa Tlas, accused reports in Der Spiegel of "dragging [our revolution] into the mud." Syrian Christians, referring to the fighting in al-Hasakah governorate, warned of a massive wave of refugees from the Christian faith community should the province fall into the hands of Islamist rebels. As a result, Assyrian/Aramaic Christians founded their first militias, such as the Sutoro and the Assyrian Military Council, which are close to the Assyrian Unity Party and fight on the front lines with the Kurdish YPG.

Kurds

Kurds form the largest non-Arab population group in Syria and, with about 1.7 million, account for almost 10 % of its inhabitants. They mostly settle in the northeast of the country, along the nearly 1,000 km Syrian-Turkish border as well as the Syrian-Iraqi border in al-Hasakah governorate and Aleppo governorate. In 1965, the creation of an Arab Belt along the Syrian-Turkish border was announced by the Syrian government and implemented in 1973, with Bedouin Arabs being settled within the belt. In addition, 20 percent of Syrian Kurds had been deprived of Syrian citizenship in the 1962 al-Hasakah census on the grounds that they had illegally immigrated to Syria from Turkey. Kurds were largely excluded from participation in the body politic.

In March 2011 the Syrian Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs announced that Kurds who do not possess Syrian citizenship would immediately have the right to work. On the second weekend of April 2011 it was announced that those Kurds within Syria who do not possess any citizenship will receive Syrian citizenship. However, this only applies to registered stateless persons (adschanib). Unregistered stateless persons (maktumin) are not taken into account, and Syrian citizenship continues to be withheld from them.

The most important Kurdish organizations are the Kurdish National Council, which consists of 15 parties, and the PYD. Since July 2012 they have been working together in the High Kurdish Committee. The PYD and other Kurdish parties maintain armed units that are active in the Kurdish-inhabited regions.

The three majority Kurdish-populated cantons of Efrîn, Kobanê, and Cizîrê proclaimed the de facto autonomous federation of northern Syria - Rojava - in early 2016.

Centers of protest

In the initial phase, groups from different parts of the population participated in the protests against the government; as the civil war progressed, foreign support, participation and influence became increasingly important factors.

In the northeast of the country, the protests were apparently initially concentrated in areas inhabited by Kurds.

Another focus of the protest movement was the city of Darʿā, a poor region dominated by tribes and agriculture, which was economically devastated after years of drought. Here, as in the Damascus Spring of 2001, participants demanded an end to corrupt economic policies and the overthrow of the Baath government of President Bashar al-Assad. There it was particularly Sunni Arabs who took part in protests. The al-Omari mosque is cited as an important gathering place for the opposition there. As is not uncommon in some other states in the Arab world, an institution such as the al-Omari mosque acts as a venue for the opposition. In the opinion of the Turkish Middle East expert Oytun Orhan of the Center for Strategic Middle East Studies (Orsam), this very fact lends the demonstrations in Syria, and especially in Darʿā, a clearly more Islamic component. In this regard, he points out that demonstrators have often uttered the slogan: "We want Muslims who believe in God". The Syrian Interior Ministry blamed the protests in Homs and Banias on radical Salafists.

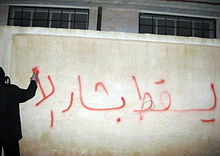

"Down with Bashar. Graffiti critical of the government from the first period of the uprising (2011)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Syrian civil war?

A: The Syrian civil war is an ongoing armed conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic that began in 2011 after the Syrian government violently stopped pro-democracy demonstrations in the city of Daraa.

Q: What other names is it known by?

A: It is also known as the Syrian uprising (Arabic: الثورة السورية) or Syrian crisis (Arabic: الأزمة السورية).

Q: Where did it start?

A: It started in 2011 after the Syrian government violently stopped pro-democracy demonstrations in the city of Daraa.

Q: Who are involved in this conflict?

A: The conflict involves a struggle between the Syrian regime and multiple opposition groups.

Q: How has this conflict developed over time?

A: This conflict has developed to be one of the most internationalized and impactful conflicts in modern Middle Eastern history.

Q: What was happening before this conflict began?

A: Before this conflict began, there were pro-democracy demonstrations taking place in Daraa.

Q: Why did these protests lead to a violent struggle?

A: These protests led to a violent struggle because they were met with violence from the Syrian government.

Search within the encyclopedia