Battle of the Bulge

Battle of the Bulge

Part of: Western Front, World War II

U.S. soldiers of 290 Reg. fight in fresh snow near Amonines, Belgium

.svg.png)

Battle of the Bulge

PreludeKesternich

- Wahlerscheid

German attackLosheimergraben

- Clervaux - Pushers - Griffin

Allied defense and counterattackElsenborn

back - St. Vith - Bastogne - Bure

German counterattack

Bottom plate - North wind

War CrimesMalmedy

- Chenogne

Significant military operations on the Western Front 1944-1945

1944: Overlord - Dragoon - Mons - Market Garden - Scheldt estuary - Aachen - Hürtgenwald - Queen - Alsace-Lorraine - Ardennes

1945: North Wind - Ground Plate - Blackcock - Colmar - Veritable - Grenade - Blockbuster - Lumberjack - Undertone - Plunder - Würzburg - Ruhrkessel - Nuremberg

The 1944/45 Battle of the Bulge, German code name Unternehmen "Wacht am Rhein," was an attempt by the Wehrmacht to inflict a major defeat on the Western Allied armies and retake the port of Antwerp. Without the port, the Allies would not have been able to land the supplies they needed to continue their advance. The Battle of the Bulge is considered the penultimate German offensive on the Western Front in World War II. Hitler hoped to take advantage of the calm created by the Ardennes Offensive on other sections of the front. Therefore, he also ordered an offensive in Lorraine and Alsace (Unternehmen Nordwind) to crush the U.S. 7th Army. Both offensives failed.

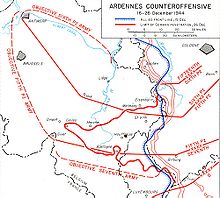

In Anglo-American parlance, the battle is referred to as the Battle of the Bulge. In the winter of 1944, three German armies in eastern and northeastern Belgium and parts of Luxembourg went on a surprise attack against the 12th Army Group. Affected were the areas around the towns of Bastogne, St. Vith, Rochefort, La Roche, Houffalize, Stavelot, Clerf, Diekirch, Vianden, and the southern eastern cantons. The operation, originally called "Unternehmen Christrose," began on December 16, 1944, and initially achieved incursions of 100 km into the enemy front line position over a width of 60 km. The target was Antwerp, through whose port the bulk of Allied supplies passed. German attacking spearheads came within a few kilometers of the Meuse River, but on the flanks troops were held up in protracted battles for places like Bastogne and St. Vith, giving the Allies time to regroup and bring up troops for a counteroffensive. After six weeks, the front was back to the way it had been. The Americans were able to more than replace their losses of soldiers and materiel within two weeks, but the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS used up important reserves. After the failure of the Ardennes offensive, the Wehrmacht leadership named "Wacht am Rhein" (Colonel General Alfred Jodl in his 1945 New Year's address) as the next objective (or, as one Wehrmacht officer put it, they moved from "Fortress Europe" to "Fortress Germany").

In total, just over one million soldiers were involved in the battle. For the U.S., the Battle of the Bulge was the largest land battle of World War II; approximately 20,000 casualties made it the bloodiest battle of the entire war for the U.S. Army.

Initial situation

The military situation in the fall of 1944

In the west, the Wehrmacht retreated from the Atlantic coast to the former borders of the Reich after heavy defeats in the Allied Operation Overlord. On the Eastern Front, too, the Wehrmacht found itself in a precarious situation since the Soviet summer offensives, which had inflicted the heaviest defeats of the war so far on a front of 2,500 kilometers. After the collapse of Army Group Center as a result of Operation Bagration in June and July, Army Group North Ukraine was also severely defeated in the Lviv-Sandomierz operation in July and August, and shortly thereafter Army Group South Ukraine was nearly annihilated in Operation Yassy-Kishinev.

Army Group North, which in early September was still able to hold Estonia, western Latvia, and a narrow land link to Army Group Center (→ Unternehmen Doppelkopf), was cut off with 27 divisions after Soviet units pushed through to the Baltic Sea as part of the Baltic operation in October. In the north, after Finland concluded the Moscow Armistice with the Soviet Union on September 4, 1944, German units had to be withdrawn from northern Norway. In the southern part of the Eastern Front, the gateway to the Balkans was open to the Red Army after Romania's defection (coup 23 August 1944) to the Allies. The Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria on September 5 (more details here). Soviet tanks reached the Iron Gate and the Romanian-Yugoslav border in early September and advanced into the Hungarian Plain in mid-September. On October 29, the battle for Budapest began. Counterattacks by the Wehrmacht succeeded in temporarily stabilizing the eastern front along a 1,200-kilometer stretch between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains toward the end of November. From July to November 1944, the Eastern Army had lost about 1.2 million soldiers. In November, 131 German divisions, 32 of which were tied up in Courland and 17 in Hungary, faced about 225 infantry divisions and about 50 large armored units of the Red Army. In terms of personnel and materiel, the German troops were far outnumbered thereafter. In the winter offensive to be expected in 1945, the collapse of the Eastern Front seemed inevitable.

In the southeast, the Red Army's successes during the Belgrade operation put the German occupation forces in Greece, Albania, and Yugoslavia in danger of being cut off. The withdrawal of Army Group E, ordered in early October, proceeded in an orderly fashion at first, but it became increasingly difficult to hold the front between the Adriatic - Drava and to Lake Balaton until November, after establishing communications with Army Group South. The Italian theater of war had lost considerable importance after the Allied invasion of Normandy. Army Group C, with 23 divisions of varying quality, was able to hold the La Spezia - Rimini line across the Apennines at the end of November. Nevertheless, the tying up of these forces by the Allies and by a lively partisan activity as a whole was of great importance. On the Western Front, the success of the Allied invasion of northern France had been finally established by the German defeats at Avranches and Falaise, which resulted in heavy losses. Abandoning Paris, Army Group B, which Field Marshal Model had taken over from Field Marshal von Kluge in mid-August, rapidly retreated eastward across the Seine. Overall, one difference from the Eastern Front was that German losses in the west were greater than those of their opponents.

After the landing of American and French troops at Toulon on August 15 (Operation Dragoon), the two German armies of Army Group G remaining in south-southwest France on the Atlantic (Bordeaux) and on the Mediterranean also had to be withdrawn; the attackers advanced rapidly through the valley of the Rhone. In early September the retreat of the Western Army came to a halt on a line that ran from the mouth of the Scheldt River through southern Holland to the Westwall south of Trier, followed the Moselle River from there, and then reached the border of Switzerland. All German units were badly battered, thinned out in personnel, and barely in possession of heavy weapons. Chronic shortages of fuel led to a loss of mobility that was particularly severe because of Allied air superiority. The West Wall was reinforced and manned with rapidly massed units. By mid-September, Army Group B (Schelde estuary to Trier) had 21 infantry divisions and 7 armored divisions facing far superior Allied forces across some 400 kilometers of front. All in all, the Wehrmacht had been pushed back to the former Reich territory on all fronts by late autumn 1944, and Aachen was the first German city to be taken by the Allies on October 21. The latter were now far superior in personnel and materiel and no longer expected to lose the initiative again.

From the German point of view, a change in these conditions was out of the question. The naval war, which on the German side could only be fought as a submarine war against enemy merchant and transport shipping, had been lost since 1943 (see Battle of the Atlantic). Since the beginning of that year, the Allies' tonnage gains exceeded their losses. Likewise, the air war in 1944 had long been considered decided. At the front as well as over the Reich territory, the Allies had absolute air supremacy. To have a chance for his counteroffensive, Hitler had to count on bad weather, which would severely hamper the deployment of fighters and bombers.

The political situation

In view of the threat of military collapse, the domestic political situation was characterized by total war. It was a matter of mobilizing the last human, material and moral forces. Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, appointed Reich plenipotentiary for the total war effort, used Nazi propaganda to strengthen the Germans' staying power or will to persevere with a mixture of threats and promises, lies and half-truths, in conjunction with his talent for oratory, and to suggest the possibility of a final victory. Rigorous measures and interventions in public, economic and private life were intended to activate the last reserves of power. Many unwilling and unbelieving people were met by the brutal terror of the omnipresent police and repressive apparatus under Heinrich Himmler.

The last European allies remaining to the German Reich after Italy, Romania, Bulgaria and Finland turned sides (Hungary, Slovakia and Croatia) were puppet states from a military, economic and political point of view, which could only be kept as allies by the German Reich with massive interventions in domestic politics. Even Philippe Pétain's French Vichy regime, which did not take part in the war but was heavily dependent on Germany, increasingly became a pure puppet regime insofar as its domain had not fallen under Allied control anyway.

Since the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, the Western powers had committed themselves to the demand of unconditional surrender, which Adolf Hitler was not prepared to accept. There were enough reasons for this attitude of the Western powers. Atrocities of the Nazi regime were known and Roosevelt and Churchill refused to negotiate with Hitler. They did not want to have their complete freedom of action after the end of the war curtailed by premature agreements with the Reich. In view of this, a special peace with the West was not to be expected.

Stalin, on the other hand, did not seem completely averse to a peace agreement. Unease between him and the Western powers was unmistakable, especially in view of the repeated delay in opening the Second Front in the West, which had been promised since 1943. There were at least two tentative contacts between German and Soviet mediators (in Sweden in 1943 and through Japan's mediation in 1944), but Hitler let them pass unused. On the whole, it seems very unlikely from what we know today that the Soviet Union would have seriously agreed to a special peace. A victory over Germany with all its consequences was an expected goal and a special peace could hardly have been communicated to the army.

In this hopeless situation, some senior German Nazi officials believed that the Western Allies would break with the Soviet Union and realize that, after a success of the Battle of the Bulge, they could crush the "common Bolshevik enemy" in the East with the help of the steadfast German army in the West.

However, the scope for a political solution to the conflict or for an active foreign policy of the empire was zero.

The offensive

Resolution

Extensive ignorance of foreign policy contexts and of the rules of democratic decision-making in the governments of his Western opponents led Hitler to arrive at an incorrect foreign policy assessment of the situation. In his view, the coalition of his Western opponents, especially that of the USA on the one hand and Great Britain with Canada, Australia and New Zealand on the other, was on the verge of collapse. By misjudging numerous foreign policy indicators and combining them into an overall assessment determined by illusions or wishful thinking, he came to the conclusion that all that was needed was a sensitive blow to the Western Allies that would bring about the collapse of the anti-Hitler coalition. The Anglo-Americans would retreat to their homelands and the German Reich would be in a position to successfully conclude the defensive struggle in the East against the threat of Bolshevization in Europe.

In Hitler's view, such a shaking of the political balance of the Western powers could only consist in an outstanding military success, in a surprising, shattering major offensive on the Western Front. The last reserves of the Wehrmacht and the people had to be mobilized for this, everything had to be put on one card, the possible downfall of the Reich had to be accepted. The basic idea of the Ardennes offensive was thus born in Hitler's mind. All available files indicate that it was he alone who came up with the idea, in his characteristic nihilistic attitude, of daring to play Vabanques and attempting to bring about a "turning point" in the war, which had long since been lost militarily, with a final and ruthless effort. A final military victory was no longer to be hoped for even on Hitler's part at this point. Rather, in Hitler's thinking, which was characterized by illusionary misjudgment and megalomania, the "shock" of a successful German offensive was still intended to create the basis for the Western public's acceptance of a political end to the war. As a last resort, the Social Darwinist Hitler had decided anyway that the German people would perish if they were not able to crown their plans with success.

"In no other operation of the war was Hitler's irrational wishful thinking more evident; never was the gap between delusion and reality greater. He swept aside all counterarguments of his military advisers, all calculations of the logisticians. He believed only in the 'power of the will'."

- Karl-Heinz Frieser: The German Blitzkriege. Operational Triumph - Strategic Tragedy

However, there were also - at least from Hitler's point of view - rational reasons to dare a last attempt in the West. In the east, there had been no decisive victory since 1941, despite seemingly more favorable conditions, and since the failure of Unternehmen Zitadelle in 1943, the initiative had been on the side of the Red Army. In the west, where the Wehrmacht had won within weeks in 1940, the distances were shorter and the traffic conditions more favorable. Moreover, Hitler now considered the fighting morale of the Western Allies to be lower than that of the Russians. If at all, he felt that only here was there still a chance to turn the war around. For Hitler, doing nothing was tantamount to surrender. And so even the last human forces were to be deployed.

Planning

"Behind this gigantic deployment plan was a single man: Adolf Hitler."

Hitler developed his reclamation of the 'law of action', which alone guaranteed him success, on the day the 3rd U.S. Army broke up the German front around the Normandy bridgehead, July 31, 1944, in a situation meeting with Generaloberst Jodl, the Chief of the Wehrmacht Leadership Staff in the OKW (High Command of the Wehrmacht) and his deputy, General Warlimont. Due to the 'followership problem', which Hitler felt not only since the assassination attempt of July 20, 1944 and in view of the currently catastrophic situation in the West and likewise on the Eastern Front, he had to develop his personal plans cautiously even in the closest circle and first convince Jodl of the necessity of offensive ideas again in the medium term. The "blindness" that Hitler is often accused of towards the 'facts' is relativized in the documents - for example, as early as July 13, 1944, when Caen was lost in the bridgehead, a "decree of the Führer on command in an operational area within the Reich" is documented, which gives detailed instructions for a restructuring of command divisions, relations between the party and the Wehrmacht, and logistical issues "in the event of an advance of enemy forces into German Reich territory."

Military command on the ground sounded different, often tactically senseless, to the ears of those concerned not only in the summer of 1944, but for Hitler there was no 'humanistic consideration' even towards his own troops - he consistently pursued strategic intentions. This is reflected in the above-mentioned situation briefing of July 31, in which he persuaded Jodl and Warlimont to adopt his views: thus Hitler interpreted the "narrowing of space" as an opportunity, for one could now "seal off Germany with a minimum of forces." Hitler certainly saw the limitation of forces, the acutely low mobility of the units, the lack of air superiority, the losses in the east, the existential problems of the previous allies with a consequence "possibly even the surrender of the entire Balkans". He calculated the retreat to the Western Wall. He foresaw Montgomery's strategy of breaking into Germany in the north. Conclusion: "These are such far-reaching thoughts that, if I were to communicate them to an army group today, they would cause horror, and I therefore believe it is necessary that a very small staff of us be deployed here." Thus is conceived the utmost secrecy of future planning. At present, he said, the enemy's supplies must be blocked and his "operations in the depths of space" made difficult by holding ports as long as possible and by logistical destruction. Hitler orders the securing of a headquarters in the west and prepares his interlocutors for reorganizations of military organization and command, familiarizing them with the idea of "assembling a staff with a few heads as intelligent as they are imaginative."

During the collapse of the defensive front in Normandy, Hitler, without prior notice, replaced Commander-in-Chief West and Commander of Army Group B, Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge with Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model in both capacities on August 17, 1944.

On August 24, 1944, immediately before the liberation of Paris by the Western Allies, the "Order on the Expansion of the German Western Position" only deals with the West Wall (including parts of the Maginot Line) and the "Moselle Line" as a "continuous tank obstacle. The Somme-Marne Line, which was still discussed several times in the daily orders, plays no role in the planning. On September 1, 1944, detailed instructions follow for the "establishment of defensive readiness" of the West Wall and the Weststellung. Weisungen für die Kampfführung im Westen (Instructions for Combat Command in the West), issued from September 3 to 9, permit comparatively flexible combat command with the aim of "gaining time for the formation and bringing up of new formations and for the expansion of the Weststellung" and prepare offensive operations in the south of the Western Front. Hitler had thus renewed the organizational structures in the rear - also regulating the command relationship between the Wehrmacht and the party in order to optimize logistical preparations.

By mid-September 1944, "within three weeks of the fall of Paris and the crushing defeat of the German Army in the Battle of France, the Wehrmacht had almost restored its equilibrium; in any case, it was no longer 'running'" and "on September 16, after his daily briefing in the 'Wolf's Lair,' the Fuehrer asked those generals in whom he had the most confidence to hold a second briefing in another room." Present, in addition to Keitel and Jodl, were Heinz Guderian, Chief of the Army General Staff, and General Kreipe, representing Goering. Hitler opened to the group his plan for an offensive in the Ardennes: "across the Meuse and on to Antwerp."

"The next day, September 17, 1944, Hitler ordered accelerated preparations for the counteroffensive. He issued orders for the reorganization of the 6th Panzer Army and, to this end, brought in a new man who would later play an important role - General Rudolf Gercke, Chief of Wehrmacht Transportation."

On September 25, 1944 - the British retreated again after their defeat at Arnhem (Hitler had been waiting to see the outcome of the battle) - Hitler "ordered Colonel General Jodl to prepare a comprehensive plan for the offensive." Keitel was put in charge of logistics. "By the beginning of October, Gercke had almost finished building up the transport system. [...] Gercke's most important task, however, was the overhaul of the German Reichsbahn."

The situation in the West had changed in the fall: "The defensive victories won by the Germans at Arnhem, Aachen, and Antwerp extended the war into the spring of 1945. These German successes thwarted Eisenhower's strategic plans and gave the Wehrmacht and the German people a new will to resist. [...] On October 8 [after Toland on October 11], Jodl submitted a draft of an offensive to be carried out in late November through the Ardennes with Antwerp as the objective." Called "Christrose" for the time being, the enterprise "was based on two premises: complete surprise of the enemy and a weather situation that made the use of Allied aircraft impossible." The utmost secrecy was ordered.

"On the morning of October 12, Jodl presented Hitler with the elaborated plan." The new code name was now "Wacht am Rhein." With his appointment as colonel, Skorzeny received special orders "behind the American lines." The next morning, October 13, von Rundstedt and Model received copies of the plan. Immediately, both drafted 'counterplans'. "On October 27, the Führer met with Rundtstedt and Model." Model tried to force a "small solution" ("Herbstnebel") that seemed more appropriate to the forces, but "Hitler made the decision - against the votes of his generals. On December 7, he approved the final draft. [...] The enterprise 'Watch on the Rhine' on the Rhine started."

"At a final meeting in Berlin on December 2, in which v. Rundstedt declined to participate," [...] Hitler conceded to Model, "one could, should the main operation fail, switch to the 'small solution' at any time. [...] On December 12, four days before the start of the offensive, all Higher Leaders were summoned to Rundstedt's headquarters. [...] Hitler spoke for two hours, and for two hours the generals sat stiffly, each with an armed SS man behind his chair, looking so grim that Bayerlein 'dared not even reach for his handkerchief.'"

Hitler's political calculation was "that he might now obtain a compromise peace if he could deal a crippling blow to one or other of his opponents." Against the Red Army, this did not seem feasible to him in terms of strength and in consequence of the 'depth of space', the most likely "law of action could be regained in the West. [...] Once Antwerp was taken, the Allies had lost the only major port (intact) [...] and the Allied armies north of the Ardennes were trapped, with their backs to the sea and without a sufficient port of embarkation. [...] Under such a defeat, Hitler believed, the coalition would break up."

"None of the generals who had to endure the torrent of words believed that Antwerp could be taken, if only because of the lack of fuel. Hitler had promised overabundant supplies, but what they had been allotted was barely enough to get them to the Meuse. They relied on getting their hands on American camps, but because of the ban on aerial reconnaissance, they did not know where any were. Nevertheless, they believed that they could reach the Meuse and inflict a heavy defeat on the Americans, provided that the buildup of forces remained unnoticed to the last."

- Chester Wilmot: The Battle for Europe, p. 554 f.

The memory of the success of the Sickle Cut Plan in May 1940 also played a role in the choice of the center of attack between Monschau and Echternach.

Hitler wanted to use a period of bad weather to offset enemy air superiority.

This weather situation then developed in mid-December. At that time, there was only a thin layer of snow in the western German low mountain ranges, and no snow at all in the lowlands. In the course of 16 December, the flow turned to west/southwest and mild air masses with rain, thaw and poor visibility spread to the Ardennes area, so that ground units would be able to operate largely unmolested by air attacks.

Two commando operations were planned to support the offensive:

- Unternehmen Greif was the code name for a detachment of German soldiers under the command of Otto Skorzeny. The English-speaking soldiers were to camouflage themselves with U.S. Army uniforms and wore the identification tags of fallen or captured U.S. soldiers. The soldiers were grouped into four infantry, three tank, two supply, and four tank destroyer companies, which were to be equipped with tanks and weapons from Allied loot. But there was a serious shortage of heavy weapons equipment. Of the 25 Sherman tanks promised, the troops received only two. The task of the soldiers of the "Griffin Command" was mainly to create confusion behind enemy lines; they were also to occupy several bridges over the Meuse between Namur and Liège.

- Unternehmen Stößer was an airborne landing operation in which paratroopers led by Friedrich August von der Heydte were to drop 11 kilometers north of Malmedy on the night of December 16-17 and block an important American supply route.

Involved forces

Three armies of Army Group B under Field Marshal Walter Model - from north to south, the 6th Panzer Army, the 5th Panzer Army, and the 7th Army - had lined up for the "decisive battle." Including the reserves of Army Group B, over 41 divisions with about a quarter of a million soldiers were ready to attack. They were concentrated on a 100-kilometer stretch between Monschau and Echternach. Model had his headquarters during the Battle of the Bulge at the former OKH headquarters (part of the Führer's 1940 Felsennest headquarters) at Hülloch near Bad Münstereifel. Hitler moved into the Führer's Adlerhorst headquarters near Bad Nauheim shortly before the offensive began.

Similar to 1940, German armored units were to make their way through the rough terrain of the Ardennes or the western parts of the Eifel and repel the Allies. The newly formed 6th Panzer Army, which included the four SS Panzer Divisions "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler", "Das Reich", "Hohenstaufen" and "Hitlerjugend", was located in the staging area of the Losheimergraben area southwest of Cologne-Bonn. It had to carry out the main attack on the northern flank by the shortest route to Antwerp. In the daily order of December 15, 1944, the commander-in-chief of the 6th Panzer Army, Sepp Dietrich, demanded the highest commitment to the last man from all Waffen SS, Army and Air Force units under his command.

American situation

In all, there were only four U.S. divisions of the 1st U.S. Army on the front section in question. The American side generally estimated the offensive capability of the Germans at this point to be only slight, and an offensive in the Ardennes was least expected. Moreover, after the failed Operation Market Garden in September 1944, the Allies were busy with their own offensive preparations north and south of the Ardennes. The British, thanks to Alan Turing at Bletchley Park, were able to decode German radio traffic. However, the most important orders on the German side were transmitted by Kradmelder - not by radio as before. The Allied military intelligence services did not succeed in deriving an "overall picture" and drawing the right conclusions from the individual building blocks that did exist and that pointed to a planned large-scale German enterprise (reports of troop deployments, individual statements by higher-ranking POWs, intercepted radio transmissions, etc.).

German soldiers in camouflaged infantry fighting vehicle at the front in the Belgian-Luxembourg area during the Battle of the Bulge, end of December 1944

Field Marshals Model and von Rundstedt and General Krebs at a meeting in November 1944

The attack (December 16-20)

Before dawn on 16 December, 14 German infantry divisions moved against only four divisions of the 8th American Corps on a front line of 100 kilometers. Supported by V-1 shells, German infantry, closely followed by armored divisions, attacked the Allied positions.

The German troops succeeded in the surprise.

U.S. forces could not hold their overstretched front sections, and a disorderly withdrawal, leaving some weapons and materiel behind, began.

"The 6th Panzer Army, which under the command of Sepp Dietrich had to make the main thrust, broke through the enemy front on the left wing and on December 18, passing Malmedy, gained the crossing over the Amblève beyond Stavelot. The right wing, however, was pinned down by tenacious American defenses already at Monschau." As a result (and because of inadequate fuel), the left wing, which had advanced 45 kilometers, also stalled well short of Liège and came under counter-operations.

The weather situation developed as hoped in these early days. The sky was almost constantly overcast and the daily highs in Aachen, for example, rose to +10 °C for several days. Only the Stößer enterprise suffered from the stormy low and was a failure. Due to the strong wind, only about one fifth of the troops reached the landing zone, the remaining paratroopers landed scattered all over the Ardennes.

"The attack of General von Manteuffel's 5th Panzer Army developed far more successfully. Even before the four infantry and the two armored corps, after strong artillery preparation in the front line, had started to storm, surprisingly [...] assault battalions had seeped into the thinly occupied American section. Already on the evening of December 17, the breakthrough on and west of the Our had succeeded in several places. The tanks crossed the river about midnight and reached the main American line about morning. The 47th Panzer Corps under General Freiherr von Lüttwitz was approaching Bastogne and threatening St. Vith."

- Gert Buchheit: Hitler the Commander, p. 161

December 18, 1944

In the morning v. Manteuffel had opened a breach south of St. Vith, and his tanks were on their way to Bastogne. A combat detachment of Patton's 10th Panzer Division reached the town in the evening, and during the night the 101st Airborne Division also arrived ahead of the Panzer Lehr Division (Bayerlein). To the north, Peiper's armored column was held up west of Stavelot by a "group of sappers assigned to run sawmills, [...which] blew up two bridges in front of it."

However, U.S. headquarters had no information about these local successes and: "Retreating troops clogged the roads and blocked the way of reinforcements marching to the front. At times, units were seized by complete panic in response to rumors that the Germans were coming ..." "On the evening of December 18, Hodges was forced to confess, 'The enemy line can no longer be fairly determined because the front is in flux and its course is somewhat unclear.'"

Reaction of the Allied Leadership

The American high command in Versailles received initial news of 'minor incursions' on a long front on the afternoon of December 16. By his own account, General Dwight D. Eisenhower was immediately convinced that it was not a local attack', but General Omar Bradley, commander of the American 12th Army Group, still considered the operation a 'diversionary attack' against 'Patton's advance in the Saar area' on the next two days. One did put two armored divisions "on the march to the Ardennes [...] the reserves of SHAEF, the 82nd and the 101st Airborne Divisions at Rheims [however] were not even put on marching readiness until the evening of the second day, 17 December." Eisenhower, however, ordered General George S. Patton and his 3rd Army, which was in the south in front of the Saarland, to make a left turn to the north to attack the advancing German forces on their southern flank.

19 December 1944

Manteuffel's troops at Bastogne "took Houffalize on the right flank and Wiltz on the left, thus enabling the city to be quickly surrounded." Infantry was to keep them at bay-the tanks were heading for the Meuse, and Manteuffel requested immediate reinforcements from Model. Model suggested to Hitler that the six reserve divisions, "since Dietrich's attack [on the right wing of the offensive] was bogged down, be thrown into the fight to exploit v. Manteuffel's breakthrough [...]. For political reasons, however, Hitler wanted the SS to strike the decisive blow and insisted that the two SS divisions be deployed in the north so that Dietrich would still have a chance. The three Wehrmacht units were the utmost he wanted to release for Manteuffel."

It was not until the morning of 19 December, at a meeting with Bradley, Jacob L. Devers, George S. Patton, and others ordered by Eisenhower at Verdun, that a semi-coordinated approach now emerged. "By the imminent breakdown[s] of the command structure of Bradley's high command" [particularly in the 1st Army under Courtney Hicks Hodges] of the front split in two by the German advance, Montgomery in the north, on his own initiative, saw fit to "send the British XXX. Corps [...] to the possible danger zone between the Meuse and Brussels." Thus, against the vehement protest of the American generals, Eisenhower considered giving Montgomery, a Briton, the command in the north, and thus also the supreme command of the 1st U.S. Army and the 9th U.S. Army, as of December 20: "The ordering intervention in the inter-Allied command structure came not a minute too soon, for the battle was already slipping out of the leadership's hands."

By the evening of December 19, the situation for the Allies had become even "much more serious. [...] No American forces were available [...] to close the twenty-mile gap between the 101st Airborne Division [in Bastogne] and the 82nd Airborne Division around Werbomont. Through this gate the Germans marched on the Namur-Dinant-Givet section of the Meuse, which was virtually undefended. [...] If the Germans crossed the Meuse, the only reserve left to stop them was the British XXX. Corps."

"Bradley's countermeasures were far behind the pace of the battle, and by the evening of December 19 he was no longer in a position to influence it." He possessed no contact with Hodges, who was trying to "reshape his disintegrating southern flank" and at the same time "reshape the northern flank"- "(too much) for one Army staff."

December 20, 1944

In the morning, Eisenhower implemented his decision - he "called Bradley himself, and a long and heated conversation ensued. [...] Eisenhower ended the conversation by saying, 'Now then, Brad, it is my order.'" The Allied front was now divided: Montgomery commanded the northern section, Bradley the southern.

In the south, the attacks on Bastogne failed. Manteuffel "drove forward himself with the Panzer Lehr Division, routed it around Bastogne, and on the 21st had it advance on St. Hubert. The 2nd Panzer Division bypassed the town to the north." The commander in the town, McAuliffe, refused to surrender. "It was clear to him that the assertion of the place tied up strong German elements. [...] The 7th Army attacking on the left of the 5th Panzer Army, whose task would have been to block the roads leading onto Bastogne from the south, achieved only some initial success. [...] Therefore, the 5th Panzer Army had to gradually branch off stronger parts from its own ranks for flank protection, so that the top of its attack wedge became thinner and thinner."

The situation became critical for the 7th U.S. Armored Division at St. Vith, which lay at the head of a deep wedge protruding into territory already captured by the Germans ("horseshoe line"). Commander Hasbrouck was out of contact and could transmit a situation report only by courier.

Command Montgomery

As early as December 18 - even before Eisenhower considered involving the Briton - Montgomery had sent "his own liaison officers to the American front:" "At the noon hour of December 20, they reported to him at first hand." When he arrived at 1st U.S. Army headquarters a little later, he was better briefed than Hodges himself. One of his staff officers reported, "The field marshal strode into Hodges' headquarters like Christ into the temple to purify him." The delegation of command in the north of the battlefield to the British field marshal led to strong reactions in the U.S. Army, the U.S. press, and the public.

Montgomery regained his composure, however, and at first it was only a matter of responding immediately to the existing chaos. It was clear that the focus of the offensive was now on the 6th Panzer Army. The 9th and 1st Army areas were shifted to the west, and the British tried to impress upon the Americans the need to withdraw exposed frontal advances (especially of the 'horseshoe') and shorten the line. Hodges, however, wanted to attack; Montgomery relented: On the night of 21 December, although the 82nd Airborne Division under Ridgway "completed the encirclement of Peiper's attacking column and established communication with the west side of the 'horseshoe' of St. Vith," ...

December 21

... but the following morning the 116th Panzer Division "had outflanked his [Ridgway's] western flank with a rapid advance in the Ourthe Valley [... and] was already attacking, deep in his rear, Hotton, thirty miles west of St. Vith." Shortly thereafter, "St. Vith was taken, and Ridgway found himself attacked with full force by the 2nd SS Panzer Corps. Far from closing the gap, the 1st Army was now being bounced back by rapid successive attacks." These attacks were carried out by twelve German divisions, including seven panzer divisions.

Situation briefing in the Luxembourg battle area, December 1944

.jpg)

Members of Kampfgruppe Hansen (LSSAH) after an attack in which the U.S. 14th Cavalry group was completely routed on the road between Poteau and Recht in Belgium on December 18, 1944 (colored).

Phases of attack December 16-24, 1944. road connections.

Armored reconnaissance unit of the 82nd U.S. Airborne Division at Heeresbach

M36 tanks of the 82nd U.S. Airborne Division at Werbomont, December 20, 1944.

German infantry on the march, December 1944

Planning and execution

Second combat phase (December 21-31)

The surprise attack on December 16 had succeeded, and the sorties behind the American lines had also had an effect. On the south wing, however, it failed to take the Bastogne transport hub (three million gallons of fuel were stored there), in the center St. Vith held its ground, and in the north the SS panzer divisions made no headway. Only Kampfgruppe Peiper, guilty of crimes, was able to break through; it failed short of the opportunity to capture a huge fuel dump (eleven million gallons) and was itself encircled. But American defensive successes rested on resistance by individual, mostly isolated units; the Allied command structure was still in the process of reorganization on 21 December. The German 5th Panzer Army in the southern area remained offensive, and the 6th Panzer Army had now moved with reinforcements to renew its attack.

Montgomery now emphatically took the lead, no longer allowing himself to be "rattled by this or that development or prediction. [...] He wanted first to stop the Germans head-on, to push them away from their strategic marching objective and force them to advance to the southwest, where they could do no harm."

The first attack by the 6th Panzer Army "was directed against the Malmédy - Butgenbach - Monschau section and continued for 48 hours without regard to casualties." The second attack (by the 5th Panzer Army) drove the U.S. 7th Armored Division back from St. Vith and across the Salm River, opening the road to Houffalize and St. Hubert. The third attack (by the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions) was directed against the already reduced frontal advance of the 82nd Airborne Division and forced the opening of the St. Vith - Vielsalm - Laroche road. "The fourth attack, aimed at extending this route through Marche to Namur, was thwarted, but southwest of Marche the 2nd Panzer Division pushed past Rochefort to the last ridge of high ground before the Meuse."

22 December From

21-22 December, the influence of the Russian high-pressure area on Central Europe began to expand again, and significantly colder and drier air slowly advanced from the east across Germany towards the Ardennes.

A thin layer of snow formed and the sky cleared.

"On the first day, the Allied 9th Tactical Air Fleet alone flew 1200 sorties against the German supply units." In addition, massive reinforcements were approaching the battle space: "On the southern flank of the breach, two corps of General Patton's 3rd American Army had swung north, and on the 22nd one of them opened a strong attack on the Arlon-Bastogne road."

In the north, Montgomery prevailed against the U.S. force command and "saved the brave defenders of St. Vith from annihilation [by timely evacuation]." He also insisted on withdrawing the 82nd U.S. Airborne Division after a breakthrough by the 2nd SS Panzer Division against the resistance of the U.S. commander. "For him, this was only a tactical maneuver; for Ridgeway, on the other hand, it was primarily a matter of honor and the fighting morale of his troops." The Americans wanted to throw all available units directly at the enemy - "but under no circumstances did Montgomery want forces destined for counterattack drawn into the defensive battle."

After the complete encirclement of Bastogne the previous day, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, in command, refused a request for surrender from General Heinrich von Lüttwitz.

December 23

Patton's relief attack on Bastogne was halted five miles from the enclosing ring and "driven back by a fierce counterattack." As the besieged's ammunition supplies dwindled, the battle for Bastogne came to a head. "The Germans waged their heaviest attack yet, smashing the southeast corner of the cauldron and taking a commanding height. Some tanks broke through to the city streets, but the Americans quickly sealed off. By morning the breach was closed again."

December 24Also

over the Christmas days, it was mostly sunny and rainless with cold nights and daytime temperatures around freezing, making Wehrmacht ground operations more difficult

due to the Allied

air superiority that now reasserted itself.

Manteuffel's push to the Meuse, which "reached the area 5 km east of Dinant," stalled as a result of fuel shortages. "The reconnaissance detachments of the 2nd Panzer Division and parts of the following Gros were cut off by American units." St. Hubert was taken by forces that had also bypassed Bastogne. "On Christmas Eve Manteuffel succeeded in obtaining immediate telephone communication with Hitler's headquarters to state the facts and make suggestions"-he was held in high esteem by Hitler-and proposed to Jodl a new plan based on the situation: He did not want to cross the Meuse on his wing, but "advance in a circular fashion northward to the near bank of the Meuse in order to cut off the Allied forces standing eastward of the river and sweep out the river bend [...] and thus also help the 6th Panzer Army forward." Manteuffel: "I concluded, emphasizing the following points: I must have answer tonight; the OKW reserves must have sufficient gasoline; I will need air support." During the night there was another contact, "but Jodl told me that the Führer had not yet made a decision. All he could do at the moment was to provide me with another armored division."

In the meantime, Model had also joined in the talks: It was still "possible to eliminate the Aachen frontal advance. Model pointed out that the forces necessary for the attack to the north could be released if the Führer abandoned his plan for the offensive in Alsace, the start of which was set for New Year's Day. Hitler rejected the last suggestion. He agreed only to the suggestion that Bastogne must first be taken." Thus Manteuffel had a free hand only for the first act.

25 DecemberHe

deployed the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division on the northwest corner. "The Germans attacked at 0300 on Christmas Day," had made two breaches by

daybreak, but were sealed off. "Of the eighteen tanks that broke through, every one was put out of action; of the infantry, not one man escaped. By mid-morning the American front had been restored."

At the same time, "the vanguard of the 2nd Panzer Division" had been waiting for a day and a half on the ridge above Dinant, impatiently awaiting fuel and reinforcements for the last final dash down the western slope of the Ardennes to the Meuse. The bulk of the division had taken Rochefort and was marching further west. However, "on its left flank the Panzer Lehr Division [...] could not get beyond St. Hubert with strong forces, and on its right flank the 116th Panzer Division had been brought to an abrupt halt between Marche and Hotton. Of the panzer reserves that Hitler had promised v. Manteuffel, one division had been diverted to Butgenbach, another was involved in the fight for Bastogne, and the third, which was only approaching Marche, had been left behind because of lack of fuel."

The German 2nd Panzer Division remained isolated. Meanwhile, "the entire American 2nd Armored Division [under General Joe Collins] held (toward) their right flank in overwhelming strength." The Germans had time to entrench themselves heavily, and by midday the fighting began.

26 DecemberThe

German vanguard at Dinant, without fuel, struggled "to avert its annihilation [...] while its division, supported by units of the Panzer Lehr Division and the 9th Panzer Division, sought in vain to break through to the vanguard's relief."

Patton's troops succeeded in "blowing up the encirclement ring around Bastogne. Only now two SS divisions and two infantry divisions were released to encircle the city again from the southeast".

There was little movement on the 6th Panzer Army front as Montgomery regrouped the troops under his command to counterattack.

"Carpets of bombs fell on all the roads. The nearer as well as the farther rear of the [German] front was under non-stop [air] attacks, which cut all communications of the army groups. Blown in two, badly battered by artillery fire, constantly attacked by swarms of fighter-bombers, the 2nd Panzer Division was all but wiped out."

December 27

Manteuffel attempted to obtain permission to retreat, but "Hitler forbade this step backward. Thus, instead of withdrawing in time, we were driven back step by step under the pressure of the Allied attacks and suffered unnecessarily heavy losses." By the evening of that day, "the forces that had been to take Dinant were rolling back into Rochefort."

The German reserves gradually reached Bastogne - "with the mission [...] to close in the city again from the southeast, and so Bastogne remained the focus of the battle until early January".

"The postponement of the attack in the north [by Montgomery] was extremely resented by Bradley and Patton." They insinuated that he did not want to use the four British divisions held in reserve. The Briton, on the other hand, was not interested in a continuous attack; he was determined to have a strong force on hand for the moment when the German reserves would be tied up. [...] Moreover, Montgomery looked far beyond the Ardennes. The British, unlike the Americans, had no fresh divisions left, and so he was very anxious to have his XXX. Corps for the coming battle in the Rhineland.

28 DecemberNow

v. Rundstedt, as Commander-in-Chief West, tried "to persuade Hitler to cease all offensive operations and to withdraw his armies before the Allies would move in full force to counterattack." At the meeting with the commanders-in-chief of the Alsace offensive prepared for January 1, 1945, Hitler stated that while the attack in the Ardennes "unfortunately had not led to the resounding success [...] that could have been expected," he claimed that the enemy had had to abandon his plans and would no longer talk of an early end to the war, so "a tremendous relaxation (had) already occurred." Success in Alsace would remove the threat against the left flank in the Ardennes, so that the offensive there "could be resumed with a new prospect of success." Model had to consolidate his position in the Ardennes, regroup troops, and "direct [a] new, more powerful attack against the Bastogne frontal advance."

Allied planning

On 27 December, Bradley proposed reinforcing Patton's advance with the 3rd Army and "making a major attack immediately with the 1st Army against the northern flank of the front advance." On December 28, Eisenhower and Montgomery discussed the proposal. The Briton warned that with "7 if not 8 armored divisions still face[ing]" in the north, it "cost (the Americans) heavy casualties, especially infantry already seriously short of replacements." He also said he still expected a German attack in the north and wanted to repel it first and then counterattack. Eisenhower conceded the merit of this consideration, "but he was very anxious that there should not be too long a wait. It was decided, therefore, that if the Germans did not attack again before then, the counteroffensive would be opened on January 3."

Officially, German propaganda in the "last days of the year [...] spoke of a 'battle of movement of the greatest magnitude'" in the Ardennes, but the chroniclers do not note any corresponding events for this period, or only position battles near Bastogne.

Offensive in Alsace (Company Nordwind)

The attack in the south of the Rhine front, planned by Hitler in connection with the Ardennes offensive on the night of New Year's Day 1945 "in order to halfway restore a clearing in the west," quickly came to a halt in the main thrust against the Zabern Depression. East of the Vosges, the attack came to nothing because the U.S. 7th Army withdrew to the Maginot Line. The thrust from the Colmar bridgehead also failed to achieve its intended success. The operations of the 3rd U.S. Army (Patton) were not affected by Unternehmen Nordwind.

The 'cross-dashed' line: also valid until the end of December (except for the US attack west of Bastogne).

U.S. patrol with a captured SS soldier, December 25, 1944.

The second phase of the attack (arrowheads to the outer line).

Prisoners of war U.S. soldiers, December 22, 1944

German grenadiers in firefight, December 22, 1944.

January 1945

The weather situation had worsened again shortly before New Year's Eve 1944 and light snowfalls down to the lowlands set in. In the further course, from January 7 on, massive snowfalls and subsequently heavy frost occurred, which massively hampered operations on both sides and are reflected in the memories of many soldiers. It was not until the turn of the month January/February 1945 that a clear thaw set in again.

"In early January, six divisions of Patton's army attacked from the south with the aim of expanding the Bastogne bulge. [...] Three fresh infantry divisions were brought in from the OKW reserve, and Dietrich had to surrender 4 armored divisions [from the north wing] to v. Manteuffel. [...] The battle that developed from this [on January 3 and 4] was the most bitter of the whole offensive and the one with the heaviest losses, especially for the new inexperienced American divisions. [...] On January 5, the German onslaught began to slacken. Any thought of capturing Bastogne was abandoned, for the troops who had been assigned to it were now urgently needed to repel the Allied counteroffensive that Montgomery had opened two days earlier against the northern flank of the bulge."

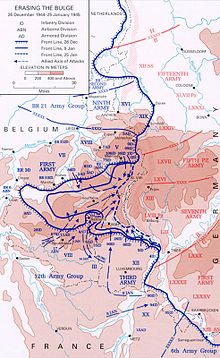

Allied counteroffensive

The British offensive (reinforced by the British 6th Airborne Division) was simultaneously joined from the west by an American attack also aimed at Houffalize, against the wedge-like German frontal advance. "Allied progress was slow, for dense fog made aerial resupply impossible and limited the possibility of using artillery."

Both operations "encountered an enemy well dug in on the wooded heights and whose positions were camouflaged by a thick blanket of snow. [...] In five days, the Americans pressing on Houffalize advanced only five miles. But this gain, small in itself, was reason enough for Model to demand permission to withdraw from the western ardennes." Seven out of ten of the German armored divisions had "only one good road in possession, [...] which (was) already under artillery fire."

"On January 8, Hitler could no longer deny that most of his remaining tanks were in danger of being trapped and authorized Model to abandon the area west of Houffalize. With this delayed and belated decision, Hitler admitted that the Ardennes offensive had failed."

- Wilmot: Battle for Europe, 1960, p. 586.

German Retreat FightingThe

German retreat was covered by slowly retreating rearguards. "By January 11, the Allied position had consolidated," and on January 12, two Patton division groups advanced around Bastogne: "The two groups (joined) near Bras. Some 15,000 elite German soldiers - including most of the 5th Parachute Division - [was trapped]. The battle for Bastogne was over. [...] On January 17, the day after the First and Third [U.S.] Armies united at Houffalize [... Bradley resumed command of Hodges' First Army [from Montgomery]."

"On January 19, a blizzard raged in the Ardennes [...] bringing the American advance on St. Vith to a halt. [...] By January 21, the blizzard had subsided, [... and] by midnight (of January 23) St. Vith was once again firmly in the hands of Kampfgruppe B [of the 7th U.S. Armored Division]. [...] The battle for the wedge was over. [...] The fighting shifted further east, into German territory."

The space gained in the Battle of the Bulge was completely lost again in the Allied counteroffensive by February 1945.

First U.S. Army tank soldiers gather around a fire on snow-covered ground near Eupen, Belgium, and open their Christmas packages (Dec. 30, 1944)

Break in fighting during the retreat in January 1945

Battle contact during the retreat in January 1945

Air Combat

As the weather cleared increasingly at Christmas and the Allies were able to use their overwhelming air superiority again, the German Luftwaffe carried out Unternehmen Bodenplatte on January 1, 1945. This was the Luftwaffe's last major air raid; its purpose was to enable the Wehrmacht to continue the Ardennes offensive. Under the strictest secrecy, hundreds of German planes attacked several Allied air bases in Belgium, damaging or destroying aircraft, hangars, and runways as badly as possible. 465 Allied aircraft were destroyed or damaged in the attack. However, due to counterattacks by Allied aircraft and unexpectedly strong flak groupings, the Germans themselves lost 277 aircraft, 62 by Allied aircraft and 172 by Allied and German flak: due to the high level of secrecy, even German flak personnel were unaware and in many cases fired on their own aircraft as they returned (self-strafing). Overall, Unternehmen Bodenplatte was a failure, as the Allies were able to make up their losses very easily, while the German Luftwaffe never recovered from the losses it suffered.

War Crimes

On the German side

In the early stages of the battle, Waffen-SS soldiers committed the war crime known as the Malmedy Massacre at Baugnez near Malmedy. In the process, 82 American prisoners of war were shot by SS soldiers of SS Panzer Regiment 1 of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler. At least two more such mass shootings are said to have occurred at Honsfeld (19 American prisoners shot) and at Büllingen (50 prisoners shot). The commander of SS Panzer Regiment 1 was Joachim Peiper. After the end of the war, Peiper and some Waffen SS subordinates were tried and sentenced (Malmedy trial).

On December 17, 1944, eleven African American soldiers were maltreated and murdered by an SS squad on a farm in Wereth (a village of eight houses near Schönberg (Sankt Vith)) (Wereth Massacre).

On December 18/19, 1944, members of the "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler" led by Peiper also committed war crimes in Stavelot, 164 Belgian civilians were murdered. In total, the Leibstandarte murdered more than 250 civilians in its combat section, Sturmbannführer Gustav Knittel was responsible for most of the shootings.

On the American side

In a massacre in Chenogne, Belgium (about eight kilometers from Bastogne), American soldiers shot several dozen German prisoners of war from the Wehrmacht on New Year's Day 1945 after receiving orders not to take prisoners. On January 3, 1945, the mayor of Chenogne found the bodies of 21 German soldiers shot in a row in the village, which was completely destroyed except for one house. The crime has not been solved. Statements by some of the U.S. soldiers involved indicate that about 60 prisoners were murdered.

U.S. soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, 119th Infantry, surrender to Kampfgruppe Peiper at Stoumont, Belgium (Dec. 19, 1944).

.jpg)

Memorial of the Wereth Massacre

Follow

The heavy losses of soldiers, tanks, combat aircraft, and fuel noticeably accelerated the decline of the German Empire. After the offensive collapsed, the Germans had finally forfeited their ability to conduct space-occupying operations on the Western Front. However, the Western Allies were not able to return to the attack until early February 1945 and did not make any significant gains in terrain until late February, while the Red Army had already advanced to the Oder River and the Pomeranian Lake District in January 1945. Dietrich's 6th Panzer Army was still fighting strong after the Battle of the Bulge. Hitler moved it (against Guderian's strong protests) not to the Vistula front but to the southeast. Before it arrived there, Budapest fell on February 13, 1945. It was given the task of repulsing the Red Army in Hungary as part of the Lake Balaton Offensive (from 6 March 1945).

With a time lag, the German population also recognized the failure of the offensive, as Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary on December 31, 1944. Contrary to the expectations of many listeners, Hitler did not even mention the offensive in his last New Year's Eve speech. In his environment, he expressed gloomy doomsday expectations and threats to Nicolaus von Below. Conversations with Waffen SS officers who had taken part in the offensive encouraged Waffen SS General Karl Wolff to seek a partial surrender for Italy.

| Victims of the Battle of the Bulge | ||||

| Fallen | Missing | Wounded | Total | |

| German | 17.236 | 16.000 | 34.439 | 67.675 |

| Allied | 19.276 | 21.144 | 47.139 | 87.559 |

Military cemeteries and memorials

The Mardasson Memorial was erected in 1950 three kilometers northeast of the center of Bastogne. It commemorates the 76,890 American soldiers who were wounded, killed or missing ('casualties') during the Battle of the Bulge. The road from the center to the monument is called 'Road of Liberation'. Nearly 8,000 fallen members of the U.S. Armed Forces rest in the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial.

In Recogne, six kilometers north of Bastogne, lies the German military cemetery Recogne-Bastogne, here lie 6,807 German war dead. Originally, about 2,700 U.S. soldiers who had fallen in the area also lay there, but these were moved to the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial in the summer of 1948.

The German Military Cemetery Lommel (Belgium) is the largest German military cemetery in Western Europe with 38,560 fallen soldiers of World War II, it also houses fallen soldiers of other battles such as the one near Aachen, in the Hürtgenwald and near Remagen.

· Numerous memorials commemorate the events

·

St. Vith

·

Bastogne

·

Stavelot

·

La Roche-en-Ardenne

·

Manhay

Joint memorial stone at the place of the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge (near Hollerath)

Memorial commemorating the victims on both sides

Film adaptations

- The Battle of the Bulge was filmed in 1956 under the title Ardennes 1944 (Attack) and in 1965 under the title The Last Battle (Battle of the Bulge).

- The film Patton - Rebel in Uniform (1970) shows the forced march of troops under the command of General George S. Patton in the Ardennes to liberate the trapped U.S. troops near Bastogne.

- The episodes Crossroads (German 'Kreuzungen'), Bastogne and Breaking Point (German 'Durchbruch') of the award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers - Wir waren wie Brüder (episodes five, six and seven), as well as

- Episode 11 of the Ken Burns documentary The War (2007) focuses on the Battle of the Bulge.

- In Everyman's War - Hell in the Bulge (2009), large parts of the plot relate to the Battle of the Bulge from the perspective of a single American soldier.

- The film Saints and Soldiers - The Real Heroes of the Battle of the Bulge (2003) is set during the Battle of the Bulge and also deals with the subject of the Malmedy Massacre.

- The film Silent Night - The Christmas Miracle (2002) is based on a true incident during the Battle of the Bulge.

Other

- The Battle of the Bulge board game, published in 2006, also revolves around the Battle of the Bulge. It is part of the "Axis & Allies" series by Avalon Hill.

- The Battle of the Bulge is also the subject of the computer games 1944, Battlefield 1942, Call of Duty: United Offensive, Blitzkrieg and Company of Heroes 2: Ardennes Assault. In the Western Front game, an entire campaign is played through. Among other things, the "Kampfgruppe Peiper" can be taken over.

- "Battle of the Bulge" is a colloquial expression in the English-speaking world for fighting obesity.

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Battle of the Bulge?

A: The Battle of the Bulge was a major German attack near the end of World War II, in Belgium, France and Luxembourg. It became the worst battle in terms of casualties for the United States.

Q: What did Germany hope to achieve with this attack?

A: Germany hoped to split the British and American Allied line in half, capture Antwerp, and then encircle and destroy four Allied armies. They hoped this would force the Allies to negotiate a peace treaty so Hitler could focus on the eastern front of the war.

Q: How did Germany keep their plans secret?

A: Germany moved troops and equipment in darkness to keep their plans secret.

Q: Why were Allied forces surprised by this attack?

A: The U.S. intelligence staff predicted a major German attack but it still surprised them because they were overconfident and too focused on their own attack plans, as well as not having good aerial reconnaissance. Additionally, they took advantage of overcast weather conditions which made it difficult for air forces to fly.

Q: How did violent resistance block German access to key roads?

A: Violent resistance blocked German access from reaching key roads which slowed down their advance and allowed Allies to add new troops.

Q: How did improved weather conditions lead to failure of this attack?

A: Improved weather conditions permitted air attacks on German forces which ultimately led to failure of this attack.

Q: What were some consequences after defeat for experienced German units?

A: After defeat many experienced German units lacked men and equipment due to high casualties during battle including 19,000 killed out of 610,000 American men involved overall in World War II making it largest most deadly battle fought by U.S..

Search within the encyclopedia