Battle of Stalingrad

Battle of Stalingrad

Part of: World War II, Eastern Front

Soviet soldiers in Stalingrad (January 1943)

Significant military operations during the German-Soviet War

1941: Białystok-Minsk - Dubno-Luzk-Rivne - Smolensk - Uman - Kiev - Odessa - Leningrad Blockade - Vyazma-Bryansk - Kharkov - Rostov - Moscow - Tula1942

: Rzhev - Kharkov - Operation Blue - Operation Brunswick - Operation Edelweiss - Stalingrad - Operation Mars1943

: Voronezh-Kharkov - Operation Iskra - Northern Caucasus - Kharkov - Enterprise Citadel - Oryol - Donets-Mius - Donbass - Belgorod-Kharkov - Smolensk - Dnepr1944

: Dnepr-Carpathians - Leningrad-Novgorod - Crimea - Vyborg-Petrosavodsk - Operation Bagration - Lviv-Sandomierz - Yassy-Kishinev - Belgrade - Petsamo-Kirkenes - Baltic States - Carpathians - Hungary1945

: Courland - Vistula-Oder - East Prussia - West Carpathians - Lower Silesia - East Pomerania - Lake Balaton - Upper Silesia - Vienna - Oder - Berlin - Prague

The Battle of Stalingrad is one of the most famous battles of the Second World War. The annihilation of the German 6th Army and allied troops in the winter of 1942/1943 is considered a psychological turning point of the German-Soviet War started by the German Reich in June 1941.

The industrial site of Stalingrad was originally an operational objective of the German war effort and was intended to serve as a launching point for the actual advance into the Caucasus. Following the German attack on the city in late summer 1942, as a result of a Soviet counteroffensive in November, up to 300,000 soldiers of the Wehrmacht and its allies were encircled by the Red Army. Hitler decided that German troops should hold out and wait for a relief offensive, which failed in December 1942. Although the situation of the inadequately supplied soldiers in the encirclement was hopeless, Hitler and the military leadership insisted on continuing the casualty-laden fighting. Most of the soldiers stopped fighting at the end of January/beginning of February 1943, partly on orders and partly for lack of material and food, and went into captivity without an official surrender. About 10,000 scattered soldiers, hiding in cellars and sewers, continued their resistance until early March 1943. Of the approximately 110,000 soldiers of the Wehrmacht and allied troops who were taken prisoner, only a few thousand returned home. In the course of the fighting for the city, over 700,000 people were killed, most of them Red Army soldiers.

Although there were major operational defeats of the German Wehrmacht during World War II, Stalingrad gained special significance as a German and Soviet site of remembrance. The battle was subsequently instrumentalized by Nazi propaganda and, more than any other battle of World War II, remains anchored in collective memory today.

Previous story

Case blue

→ Main article: Blue case

After the German Reich's attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, and the Red Army's counteroffensive in the winter of that year, a new offensive was planned for the summer of 1942 under the code name Fall Blau, with the goal of capturing the Soviet oil fields in the Caucasus.

The city of Stalingrad was classified as a significant operational target partly because of its industrial and geographical importance and partly because of its symbolic value:

- Stalingrad was of great strategic importance for the Soviet Union, as the Volga River was a major waterway. The city stretched 40.2 kilometers in a north-south direction along the west bank of the Volga, but was only 6.4 to 8 kilometers wide at its widest point. The Volga, 1.6 kilometers wide at this point, protected the city from enclosure. The river was part of an important supply route for armaments transported from the United States via the Persian Corridor and the Caspian Sea to central Russia under the Lend-Lease Act. German plans aimed at a renewed push on Moscow were therefore discarded, as Hitler considered the Caucasian oil fields more important for further warfare. The conquest of Stalingrad was intended to cut off this transport route and secure a further advance of the Wehrmacht into the Caucasus with its oil deposits near Maikop, Grozny and Baku.

- The symbolic significance of the name Stalingrad was additional incentive for both Stalin and Hitler to achieve military victory. Stalin had defended this city during the Russian Civil War as army commissar of the Southern Front, including mass shootings of alleged saboteurs to consolidate the power of the WKP(B). In 1925 the city was renamed from Tsaritsyn to Stalingrad.

According to calculations of Stalin's High Command, in 1942, despite one million fallen Red Army soldiers and over three million soldiers taken prisoner of war in Germany, there were still 16 million Soviet citizens of weapons age facing the German armies. The armaments industry, which had moved behind the Urals, produced 4,500 tanks, 3,000 combat aircraft, 14,000 guns and 50,000 grenade launchers by 1942. On the German side, one million soldiers were killed, wounded or missing; of the tanks involved in the attack, only one in ten was still functional.

Hitler, however, assumed that "the enemy had largely used up the masses of his reserves in the first winter of the war". Based on this misjudgment, he ordered simultaneous attacks on Stalingrad and the Caucasus. This fragmented the limited German offensive forces and led to a spatial overstretching and thinning of the front. The success of the plan depended on the fact that the extensive flank of Army Group B along the Don River could be defended by the armies of allied countries, while German armies were to lead the actual offensive operations. The main attacking force was the approximately 200,000 to 250,000 strong German 6th Army under General Friedrich Paulus. It received support from the 4th Panzer Army under Colonel General Hermann Hoth with various subordinate Romanian units.

German advance on Stalingrad

Due to the German advance towards Stalingrad and the Volga, the Stalingrad Front was formed on July 12, 1942 by order of the Soviet High Command from the command of the disbanded Southwest Front. It was initially commanded by Marshal Timoshenko and from July 22 by Lieutenant General V. N. Gordov. It consisted of the 62nd, 63rd, and 64th Armies and was reinforced by the 51st, 66th, and 24th Armies, the 1st and 4th Panzer Armies, and the 1st Guards Army by the end of August.

Strong Soviet resistance in the Danube arc, as well as fuel shortages, caused a delay in German action for several weeks. On July 17, 1942, the leaders of the German 6th Army encountered the vanguards of the Soviet 62nd and 64th Armies, which received support first from the 4th Panzer Army and later by the 1st Panzer Army. The strong frontal resistance of Soviet troops during the Kesselschlacht near Kalatsch (July 25-August 11) forced the German Wehrmacht to deploy its forces more widely. Due to the increasing width of the battlefield, the Stalingrad front was divided on August 7 on the orders of the Stavka and an additional southeastern front was formed, command of which was given to Colonel General Yeremenko. In terms of numbers, the Soviet High Command was able to draw on some 1,000,500 men to defend Stalingrad, with 13,541 guns, 894 tanks, and 1115 aircraft at its disposal.

Only on August 21, 1942, the German 6th Army with the LI. Army Corps (General der Artillerie von Seydlitz-Kurzbach) was able to cross the Don River at Kalatsch and begin the advance to Stalingrad. The German troops were joined by the 62nd Army under Lieutenant General A. I. Lopatin, the 63rd Army under Lieutenant General V. I. Kuznetsov, and the 64th Army under Lieutenant General V. I. Chuikov. It should be taken into account that the Soviet army of that time, due to different organizational structures, in comparison with a German one, was more like a German corps in terms of personnel and material. It follows from this that at the beginning of the battle both sides were about equally strong - if one assumes that a German army consisted of four to five army corps, depending on the situation, equipment and mission.

Advance detachments of the German 16th Panzer Division reached the Volga River north of Stalingrad at Rynok at 6 p.m. on August 23, but were soon forced into defense against strong Soviet counterattacks from the north. On the same day, a massive German air attack with 600 aircraft had resulted in the deaths of thousands of civilians in Stalingrad, who were ordered by Stalin not to be evacuated. German Air Fleet 4 dropped a total of about one million bombs with a total weight of 100,000 tons on the city.

For a long time, the Stavka prevented the population from leaving the city, which was overcrowded with refugees, because Stalin believed that their staying would boost the morale of the fighting soldiers. As a result, women and children were forced to help build defensive positions, dig tank trenches, and even fight in some cases. In August 1942, there were about 600,000 people in the city. In the first days of the battle, air raids killed over 40,000 civilians. It was not until the end of August that residents began to be relocated to areas beyond the Volga River. But it was too late for a complete evacuation of Stalingrad with such a large population. About 75,000 civilians had to remain in the destroyed city. Neither the Red Army nor the Germans showed any consideration for the civilian population. Numerous inhabitants had to live in holes in the ground. Many froze to death in the winter of 1942/1943; others starved to death because there was no food left.

On August 23, 1942, when German advance units broke through north of Stalingrad to the Volga River, the Soviet High Command, on Stalin's instructions, imposed a state of siege on the city. From that day on, responsibility for the immediate defense of the city rested with Colonel General Andrei Yeremenko, who, after Gordov's recall on Stalin's personal instructions, had taken over the organization and direction of the Soviet Stalingrad front. He was assisted by Nikita Khrushchev as political commissar and Major General I. S. Varennikov as chief of staff. Order No. 227 issued by Stalin on July 28, 1942, under the slogan "Not a step back!" led to the formation of firing squads and punitive battalions for Red Army soldiers accused of lack of combat readiness or cowardice.

German Assault Gun III (Autumn 1942)

Battle History

The course of the battle is divided into three major phases.

- Phase 1: The 6th Army tries to conquer the city of Stalingrad from late summer 1942. After capturing up to 90 percent with heavy losses on both sides, the situation turns in favor of the Red Army.

- 2nd phase: The Red Army troops encircle the 6th Army over a large area in the Uranus enterprise. The weakly equipped Romanian units assigned to flank security cannot withstand the Soviet offensive.

- Phase 3: After Hitler's prohibition to attempt a breakout, the 6th Army is holed up waiting for outside help. In Unternehmen Wintergewitter, the Germans make an attempt to reach the cauldron, but ultimately fail due to Red Army resistance and the subsequent collapse of Italian units on the middle Don River. After heavy losses due to combat, cold and hunger, the remnants of the 6th Army surrender in February 1943.

First attack phase of the 6th Army

→ Main article: Attack on Stalingrad

On September 12, 1942, Hitler demanded that Paul take Stalingrad. "The Russians," Hitler said, were "at the end of their strength." After the declaration of a state of siege, Lieutenant General A. I. Lopatin was temporarily replaced as commander-in-chief of the 62nd Army by Chief of Staff N. I. Krylov and replaced by Lieutenant General Vasily Chuikov. General Lopatin had doubted that he could hold the city against the German troops in accordance with Stalin's orders. The command of the 64th Army, which Chuikov held until August 4, had already been transferred to General M. S. Shumilov.

On September 13, the major German attack began with dive-bombing and massive shelling from field artillery and mortars on Stalingrad's inner defensive belt. In the process, the 295th Infantry Division moved against Mamayev Hill and the 71st Infantry Division against Stalingrad's main railway station and the central ferry terminal in the city center. The German XIV Panzer Corps (16th Panzer, 60th, and 3rd (mot.) Divisions), deployed to the north of the city, had the task of securing the eastern end of the Kotluban corridor between the Don and Volga rivers against multiple attacks by the Soviet 1st Guards Army, 24th Army, and 66th Army (Lieutenant General A. S. Shadov). The very next day, Commanding General von Wietersheim was deposed by Hitler for suggesting that the loss-making attacks on Stalingrad be called off altogether. The new commander, Maj. Gen. Hans-Valentin Hube, ordered a new attack in the Orlovka Frontal Advance on Sept. 27, which quickly collapsed, requiring the 94th and 389th Infantry Divisions to be brought to him as reinforcements. Opposite the Soviet 21st Army (Lieutenant General A. I. Danilov), the VIII. Army Corps (General of Artillery Heitz) with the 76th and 113th Infantry Divisions held the Don section between Shishikin and Kotluban. The further the German LI. Army Corps advanced into the inner city, the fiercer Soviet resistance became.

The Soviet defenders turned every foxhole, house, and crossroads into a fortress. On September 14, the 13th Guards Rifle Division under Major General Rodimtsev arrived as reinforcements to halt further German advance. On September 21, the 284th Rifle Division (Colonel Batyuk) also reached the western bank of the Volga and secured between the "Red October" steelworks and Mamayev Hill. On September 27, the hard-fought Mamayev Hill remained in German possession on the northwest side, with only the eastern slope held by the 284th Rifle Division. By September 29, the Orlovka frontal salient had been cut off, and the trapped Soviet units fought to their own destruction. In late September 1942, the 6th Army High Command shifted the center of attack to the industrial complexes north of the city. The 284th Rifle Division relieved the 13th Guards Rifle Division on Mamayev Hill. The fighting was particularly fierce around the two railroad stations, the grain silo, Pavlov House, Mamayev Hill (designated by the Germans as Altitude 102, also known as Mamai Hill), and the large factories located to the north with the "Red October" steelworks, the "Barricades" gun factory, and the "Dzerzhinsky" tractor plant.

To counter German air supremacy, the best pilots from all fronts were brought in and elite units such as the 9th Guards Fighter Regiment were formed. Night bombers, which according to Soviet figures dropped 20,000 tons of bombs in the Battle of Stalingrad, as much as the German Luftwaffe dropped over England in 1941, robbed German soldiers of their nightly rest and kept them in a state of constant anxiety and tension.

The German units only succeeded in bringing the almost completely destroyed city under their control during Operation Hubertus (November 9-12), which was hailed as a great victory by Hitler in his speech at the Löwenbräukeller on November 8, 1942. The 62nd Army under Lieutenant General Chuikov now held only a narrow strip a few hundred meters wide along the Volga River and small parts to the north of the city.

Second phase: Operation Uranus - encirclement of the 6th Army

→ Main article: Operation Uranus

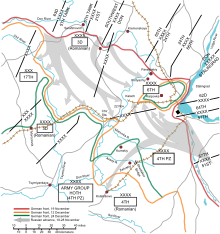

By "Operation Uranus", which started on the morning of November 19, 1942, the troops of the Wehrmacht were surrounded by Soviet forces within five days. These were broken through the lines of the Romanian 3rd Army in the west on the Danube front under Rokossovsky and on the southwest front under Vatutin, and in the southeast on the Stalingrad front under Andrei Ivanovich Yeryomenko through the lines of the Romanian 4th Army.

To this end, the 5th Panzer Army (General Romanenko) from the Serafimovich bridgehead on the Don River and the 21st Army (under Lieutenant General Chistyakov as of October 14) from the Kletskaya bridgehead each made a breakthrough to the south. The Romanian 3rd Army (General Petre Dumitrescu) facing them could not hold out for long, as it had to secure an overstretched flank and was insufficiently equipped for the task. Thus, to defend against the Soviet tanks, these units had mainly 3.7-cm PaK drawn by horse-drawn vehicles, which were practically ineffective against the Soviet T-34 tanks. The Red Army advance proceeded rapidly, in part because bad weather prevailed at the time of "Operation Uranus" and the German Luftwaffe was unable to intervene. When the weather improved, the Luftwaffe found itself unaccustomed to the defensive, as this battle saw the first use of the Lavochkin La-5 in larger numbers, a type of aircraft with comparable performance to the German Fw 190 and thus capable of providing effective cover for its own strike aircraft.

Behind the Romanian 3rd Army was the XXXXVIII Panzer Corps, consisting of the 22nd German and the 1st Romanian Panzer Divisions. On Hitler's orders, it was thrown towards the Soviet troops in order to stabilize the situation. The armored corps, primarily equipped with completely obsolete Czech 38(t) armored fighting vehicles, lay in readiness in barns and stables. Mice, massing in the straw, had eaten their way through the vehicles' coverings and electrical cables, leaving only about 30 tanks ready for action, which, due to their small numbers and fairly low combat strength, were unable to stop the Red Army's attack. The commander of that tank corps, Ferdinand Heim, served as a scapegoat afterwards, was expelled from the Wehrmacht, and was not entrusted with a command in Boulogne again until 1944.

On November 20, the attack by the 57th Army (General Tolbuchin) of the Stalingrad Front (Yeremenko) also began in the south of Stalingrad. The Soviet 13th Armored Corps (Major General T. I. Tanashishin) broke through the northern wing of the Romanian 4th Army at Krasnoarmeisk. In the process, the Romanian 20th Infantry Division under General Tataranu was pushed northward to the German IV. Army Corps to Beketovka and later encircled with this corps still subordinate to the German 4th Panzer Army and the 6th Army. The second attack wedge, the 4th Mechanized Corps (Maj. Gen. V. T. Wolski) of the 51st Army (Maj. Gen. N. I. Trufanov), broke through the Romanian VI Corps front at the Tundutovo railroad station and could not be stopped by the German 29th Infantry Division. The breakthrough at the Romanian 4th Army and at the German 4th Panzer Army enabled the Soviet tank spearheads to make a double pincer movement that met at Kalach on the Don River on November 23, closing the ring around the German 6th Army, which was encircled in the Stalingrad area.

The Wehrmacht now found itself in a dangerous dilemma: In the event of defeat at Stalingrad, the Red Army could have broken through toward Rostov to the Black Sea, thus cutting off not only Army Group Don but also the entire Army Group A - which would have meant the loss of the entire southern wing of the German Eastern Front. However, a retreat from the Pre-Caucasus would otherwise have meant that the Caucasian oil fields would have moved into an unreachable distance and a planned advance towards Iran or India would have become completely illusory. Hitler, however, did not want to admit this to himself and therefore delayed the order for Army Group A to withdraw. Only when the defeat of the 6th Army became apparent with the failure of the relief attempt, the retreat of Army Group A was initiated on December 28, 1942, which, due to the late decision, partly turned into a loss-laden flight over hundreds of kilometers, during which not infrequently all heavy weapons, vehicles and tanks had to be left behind simply because of the worsening permanent fuel shortage.

Third phase: conquest of the cauldron

Kettle Battle

Since November 22, the 6th Army was completely encircled by Soviet troops. On that day, the 4th Panzer Army (IV Army Corps) and Romanian (two divisions) units, which were also encircled, were also subordinated to it. Paul and his staff planned to first stabilize the fronts and then break out to the south. Even at that time, however, there was a lack of the necessary equipment for such an undertaking.

On November 24, Hitler finally decided to supply the Kessel from the air after Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring had assured him that the Luftwaffe would be able to fly in the required minimum of 500 tons of supplies daily. Allegedly, both Goering and Hitler were informed by the Army and Air Force general staffs that this was not possible. The highest supply level was reached on December 19, 1942, when 289 tons were flown in, but on some days no supply flights could be made because of bad weather. From November 25, 1942, to February 2, 1943, an average of only 94 tons could be flown in daily instead of the promised 500 tons.

On November 24, the soldiers' rations were cut in half and the bread allotment was set at 300 grams per day and subsequently reduced to 100 grams, and towards the end to only 60 grams per man. This meant only three slices of bread per day, which never met the needs of a fighting soldier. The troops visibly starved over the next few weeks.

Air supply, for which the VIII Air Corps was primarily responsible, further collapsed during the raid on Tazinskaya. Fliegerkorps der Luftflotte 4 was responsible for, collapsed further when, during the raid on Tazinskaya as part of the Middle Don Operation, Tazinskaya (24 December 1942) and Morozovskaya (5 January 1943) airfields to the west of the cauldron were used as launching pads for flights into the cauldron and Pitomnik (16 January 1943) airfields within the cauldron. The airfields Tazinskaya (December 24, 1942) and Morozovskaya (January 5, 1943) west of the encirclement were captured by the Red Army as a take-off point for flights into the encirclement, and Pitomnik airfield (January 16, 1943) inside the encirclement was captured by the Red Army, and supplies could only be delivered from the makeshift Gumrak field airfield. Most of the encircled soldiers therefore did not die as a result of fighting, but from malnutrition and hypothermia. The wounded soldiers who were flown out did not come to Germany, but to military hospitals in occupied areas, so that the sight of the emaciated and almost starving soldiers would not show German civilians the real condition of the troops.

Another essential problem for the soldiers and officers in the cauldron was that the wounded also had to be transported away via these supply airfields. Especially after only the makeshift airfield at Gumrak was available, the aircrews often had to use force of arms to keep the desperate from clinging to the planes, which they did not always succeed in doing. It happened, for example, that men clung to the landing gear of planes taking off until their strength failed them and they crashed.

At that time, the Soviet army took advantage of the work of German communists (including Walter Ulbricht, Erich Weinert and Willi Bredel). The main task of the Soviet propaganda department at the time was to play 20- to 30-minute programs of music, poetry, and propaganda on mobile gramophones and broadcast them over huge loudspeakers. Among other things, the popular old hit song with the refrain "In der Heimat, in der Heimat, da gibt's ein Wiedersehn!" was broadcast over these loudspeakers.

Other means of propaganda, including the slogan "Every seven seconds a German soldier dies. Stalingrad - mass grave." which followed the monotonous ticking of a clock, and the so-called "deadly tango music" (Death Tango) provided additional demoralization of the soldiers in the cauldron. Most propaganda broadcasts of this type, however, initially led to increased shelling of enemy positions on the orders of the German generals, so that a large number of the Soviet forces were killed in these operations. Due to dwindling German ammunition supplies, however, this shelling became weaker and weaker over time, and "listening away" subsequently became almost impossible.

Finally, an acoustic means of demoralization also used was the characteristic "scream" of the Soviet Katyushas (multiple rocket launchers) called "Stalin's organ" by the Germans.

Stalingrad Airlift

Essential for the continuation of the fighting in the Kessel was the supply of the trapped German troops with ammunition, supplies and food via an air bridge. The Inspector General of the Luftwaffe, Erhard Milch, was instructed by Adolf Hitler to ensure this. Ju 52s led by Lufttransportführer 2, converted bombers such as the He 111, and Ju 86 and Fw 200 training and passenger aircraft were used for this purpose. Even 27 of the four-engine bomber He 177A-1 of Fighter Wing 50 were used. Lufttransportführer 1, also called Lufttransportführer Morosowskaja, led the He 111 units.

The delivery of the Army's required daily supply of at least 500 tons of supplies promised by Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief Hermann Göring was never achieved. The highest daily output of 289 tons of goods was achieved by 154 aircraft on 19 December 1942 in good weather conditions.

In the first week beginning November 23, 1942, with an average of 30 flights per day, only a total of 350 tons of cargo was flown in, of which 14 tons were provisions for the 275,000 men in the Kessel (this is 51 grams per person, equivalent to two slices of bread). Seventy-five percent of the cargo consisted of fuel for the return flight, for the tanks, and for the Bf-109 escort fighters in the Kessel. In the second week, a total of 512 tons was transported, a quarter of the required quantity, of which only 24 tons was food. As a result, more draft animals already had to be slaughtered to make up for the shortage of food. Since the troops still fit for action had priority in the supply, the wounded and sick soon received no more rations and fought fiercely for the last places in the transport planes.

From November 24, 1942, to January 31, 1943, the Luftwaffe had the following losses of transport aircraft in supply flights:

| Aircraft type | Quantity |

| Junkers Ju 52/3m | 269 |

| Heinkel He 111 | 169 |

| Junkers Ju 86 | 042 |

| Focke-Wulf Fw 200 | 009 |

| Heinkel He 177 | 005 |

| Junkers Ju 290 | 001 |

| Total | 495 |

A total of 495 aircraft were thus lost. This corresponded to 5 squadrons and thus more than one air corps.

Accordingly, the losses amounted to about 50% of the aircraft deployed. In order to compensate for the loss of pilots, the Luftwaffe's training program was halted in favor of the air supply of Stalingrad, and the trainers who were thus freed up, but who were actually irreplaceable, were burned out as transport pilots. As the war progressed, this led to a noticeable deterioration in the training level of new pilots. In addition, enemy flights in other theaters of war were significantly reduced in order to save fuel for the mission in Stalingrad.

German relief attempt - "Unternehmen Wintergewitter" (Winter Storm Company)

→ Main article: Winter Storm Company

To command the forces standing in and around Stalingrad, the new Army Group Don was formed on November 26, 1942, from AOK 11 under the command of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, with headquarters at Novocherkask. A few days earlier, Manstein had joined Field Marshal von Weichs at Army Group B headquarters in Starobelsk for a briefing on the difficult situation facing the 6th Army. Hitler had forbidden an immediate attempt to break out because he wanted to maintain the prestige of "German soldiers standing on the Volga" and ordered three panzer divisions to be brought in for the relief effort to Stalingrad. In addition to the trapped 6th Army, Army Group Don was assigned the 4th Panzer Army, including the remnants of the Romanian 4th Army subordinated to it, in the Kotelnikovo area. To this were added the combat groups and alert units of the XVII Army Corps at the Chir section, as well as the remnants of the Romanian 3rd Army. After the 7th Airborne Field Division, which had been supplied via Morovskaya, was completely crushed in Soviet attacks at Nizhne Chirskaya, the newly formed Hollidt Army Division took over the defense at Chir. The Don bridgehead at Chirskaya was held by Kampfgruppen Tzschökell and Adam, south of it secured by Kampfgruppe von der Gablenz. To the west, on the southern bank of the Chir, the 11th Panzer Division, the 336th Infantry Division, and Kampfgruppe Stumpfeld and Gruppe Schmidt secured. The XXXXVIII Panzer Corps, whose command was at Tormosin, acted as a rear.

On December 12, 1942, the relief attack was launched by the 4th Panzer Army under Colonel General Hoth in "Unternehmen Wintergewitter" to relieve the 6th Army. At first, the LVII Panzer Corps (General der Panzertruppe Kirchner) entered with only the 6th Panzer Division (General Raus) and the 23rd Panzer Division (General Vormann). After the 17th Panzer Division (Lieutenant General von Senger and Etterlin) also arrived on the battlefield on December 17, the southern bank of the Myshkova River was won in the fight. In addition, the 6th Army, under the cue "Thunderclap," would have had to attempt a breakout from the encirclement in the direction of Army Group Hoths to bring the operation to a successful conclusion. Starting from Kotelnikovo south of Stalingrad, this relief attack was severely hampered 48 kilometers before reaching the cauldron by strong opposition from the Soviet 2nd Guards (Lieutenant General Rodion Malinovsky) and the 5th Shock Army and the 7th Panzer Corps (Major General Rotmistrov). Further northwest on the middle Don River, the major Soviet offensive Operation Saturn, launched as early as December 16, which initiated the collapse of the Italian 8th Army and thus threatened the entire Army Group South with strangulation, forced the immediate cessation of the relief of Stalingrad. The attempted breakout of the 6th Army demanded by Manstein was considered by the leadership around Paulus to be a "catastrophe solution" in view of the poor condition of their own troops. Hitler repeatedly rejected the attempt to break out of the encirclement, most recently on 21 December, because the motorized units of the 6th Army would have too little fuel to cover the distance to Hoth's Panzer Army. The relief attempt had to be abandoned on 23 December. The situation of the German soldiers and their allies thus finally became hopeless.

Operation Kolzo" and the End of the 6th Army

At the end of September 1942, by order of the Soviet High Command, the Don Front had been formed by renaming the Stalingrad Front, and the supreme command had been given to Colonel General K. K. Rokossowski had received the supreme command. The inventory initially included the 21st, 24th, 63rd, 65th, and 66th Armies, and from January 1, 1943, the 57th, 62nd, and 64th Armies also joined the front, all of which participated in the encirclement of the 6th Army. Despite the hopeless situation, Colonel General Paulus still refused the Soviet side's demand for surrender on January 8, 1943.

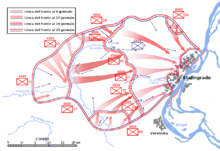

The armies of the Don Front then launched their last major offensive against the remnants of the 6th Army on January 10, 1943, in Operation Kolzo (Russian: Ring). The goal was to "smash" the Stalingrad encirclement. On the one hand, the ring around the encircled troops was tightened, on the other hand, the immediate front moved further to the west, which cut off the 6th Army even more from its own troops. In this process, the Soviet troops also succeeded in capturing the two airfields of Pitomnik (January 16) and Gumrak (January 22). From then on, Wehrmacht aircraft took off and landed only at the makeshift airport "Stalingradski", until it too fell into Soviet hands and supply material could only be dropped over the cauldron.

Finally, on January 25, the Wehrmacht forces were split into a southern and a northern encirclement. On January 28, the northern encirclement was again split into a central and a northern encirclement.

By radio message from the Führer's headquarters, Paulus was promoted to Field Marshal General on January 30, 1943. Since no general field marshal of the Wehrmacht had ever been taken prisoner before, Hitler wanted to use this promotion to put additional pressure on Paulus to hold his ground at all costs - or indirectly to urge him to commit suicide.

On the same day, an address to the German people from the Hall of Honor of the Reich Air Ministry in Berlin was announced. Since the "Führer" was deliberately never to speak in connection with a clear defeat, the "second man of the Reich," Goering, was designated to prepare the Germans for it. The British knew of Goering's twelve o'clock deadline, broadcast on the radio, and caused an embarrassing delay of one hour with a few high-speed bombers over the Reich capital. From the generally transparent speech formulas, the listeners could then infer the hopeless situation of those trapped inside.

On January 31 in the morning troops of the Red Army entered the department store "Univermag", in the basement of which was the headquarters of the 6th Army. At 7:35 a.m. the radio station there gave its last two messages: "Russian is at the door. We are preparing destruction." Shortly thereafter, "We are destroying." After further Red Army attacks on the remaining German positions, Major General Roske, commander of the 71st Infantry Division, surrendered in the southern kettle. Immediately afterwards, Major General Laskin, Chief of the General Staff of the 64th Soviet Army, arrived at the 6th Army headquarters, where surrender negotiations then began. On the same day, the Mittelkessel commanded by Colonel General Heitz also surrendered.

The commander-in-chief of the 6th Army Paulus, who was taken prisoner at the same time on that day, was interrogated by the then Colonel General and later Marshal of the Soviet Union Konstantin Rokossowski in the night of February 1. Hitler raged when he learned of the capture of the commander-in-chief. Paul had expressly forbidden all officers to commit suicide on the grounds that they would have to share their soldiers' fate of now going into captivity.

Operation Kolzo came to a definitive end only with the cessation of fighting in the Northern Kessel, which - with the remnants of 21 German and two Romanian divisions barely capable of fighting and also completely under-supplied and with General der Infanterie Karl Strecker as commanding general - surrendered on February 2, 1943.

At noon on February 3, the OKW had a special announcement read out on the Greater German Radio, declaring that the 6th Army had fought "under the exemplary leadership of Paulus to the last breath," but had succumbed to "superior strength" and "unfavorable conditions." It was declared to be a historical "bulwark" of a not German, but "European army" that had vicariously led the fight against communism.

The claims of the Reich radio stations culminated in the fact that all soldiers of the Sixth Army had met their death. The special report did not mention that a total of 91,000 soldiers had been taken prisoners of war, which the BBC had already reported and which led to more people in Germany getting their information from foreign "enemy broadcasters." Goebbels, who had launched this report, had been publicly exposed as a liar.

The Nazi regime ordered three days of national commemoration: Bars, cinemas, etc. were closed, radio broadcast only serious music. However, mourning flags were prohibited, as were black borders in the press.

Scattered Wehrmacht units, however, continued to fight in the Stalingrad area into March. As the last documented combat action, an NKVD report notes an attack by German soldiers on March 5. Two Soviet soldiers were wounded in the attack. After a search operation, eight German officers were shot.

Meteorological aspects

Many documentaries, narratives and reports are dominated by the memory of the Russian winter weather that had prevailed during the battles for Moscow after the partly traumatic experiences of the first winter on the Eastern Front. However, the weather during the second and third phases of the battle was not consistently cold, nor was it exceptional. Of military importance during this period, in addition to the heavy frost phases (mainly toward the end of the battle), were the visibility conditions and thus the flying weather. During the bad weather phases, visibility was sometimes so poor that either no pilots or only very experienced pilots were able to ascend, further worsening the supply situation.

Weather history

At the beginning of the Russian offensive there was only light frost and mostly poor visibility. Then, after the encirclement, the last week of November saw winter weather with snowfall and mostly light frost. Then, just before the turn of the month, a thaw with rain set in, making the roads poorly passable.

This was followed by several days of changeable weather and repeated rain and snowfall. The ice on the Volga was only continuous in the marginal areas, and the ice cover was not sustainable. Visibility was generally poor at this time. From December 10, it cleared up and there were then no more dew phases during the day. However, the frost was only moderate. Around December 14, there was a brief thaw, followed by clearer weather with nighttime frosts down to -15 °C.

Then, shortly before Christmas, poor visibility again with changeable and partly light thaw. On Christmas Eve, heavier snowfall set in and on the Christmas days, the temperature dropped to as low as -30 °C for the first time. However, it cleared up and there was good flying weather.

On New Year's Day, a light thaw set in again for 2-3 days before moderate frost to about -15 °C set in again from January 4. Subsequently, the weather became somewhat milder again with short periods of dew. From 11 January, heavy snowfall set in, followed by very heavy frost in some areas down to -30 °C.

Operation Kolzo

Paulus, who was promoted to Field Marshal at the last minute on January 30, goes into Soviet captivity on January 31, 1943.

Soviet soldiers in the destroyed city center, February 2, 1943.

Soviet infantrymen in firing position on a roof during the fighting around Stalingrad, January 1943.

Air raid on Stalingrad (September 1942)

Encirclement of the 6th Army by Soviet forces

Sketch of the units involved: red = armies of the Don Front, black = divisions of the 6th Army.

Soviet snipers enter a destroyed house (December 1942)

War Council of the Stalingrad Front in December 1942 (Nikita Khrushchev on the left, Andrei Yeremenko on the right).

German soldier with Soviet submachine gun in cover among rubble in late autumn 1942 (photograph taken by a German propaganda company).

Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach (left) with Friedrich Paulus in Stalingrad, 1942

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Battle of Stalingrad?

A: The Battle of Stalingrad was a military conflict fought during World War II between Nazi Germany led by Adolf Hitler and the Soviet Union led by Joseph Stalin for control of the city of Stalingrad.

Q: Who supported Germany in this battle?

A: During the Battle of Stalingrad, Germany got support from Italy, Hungary, Croatia and Romania.

Q: When did this battle take place?

A: The Battle of Stalingrad took place between 23 August 1942 and 2 February 1943.

Q: Why did Hitler want to capture Stalingrad?

A: Hitler wanted to capture Stalingrad because it was named after Joseph Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, thus it would embarrass him. He also wanted to gain control over an important industrial city and transport route on the Volga River.

Q: How long did this battle last?

A: The Battle of Stalingrad lasted five months, one week, and three days.

Q: What were some extreme measures taken due to limited supplies during this battle?

A: Due to limited supplies during the Battle of Stalingrad, soldiers and civilians had to resort to eating rats, mice, and even cannibalism.

Q: What were HIWIs?

A: HIWIs (or Hilfswillige) were Eastern European volunteers who made up about one quarter of German Sixth Army's soldiers during the Battle of Stalingrad.

Search within the encyclopedia