Swastika

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Swastika (disambiguation).

A swastika (also Svastika, Suastika; from Sanskrit m. स्वस्तिक svastika 'good luck charm') is a cross with four uniformly angled arms of approximately equal length. They may point to the right or left, be right-angled, acute-angled, shallow-angled or round-angled, and be connected with circles, lines, spirals, dots or other ornaments. Such signs, the oldest dating from about 10,000 BC, have been found in Asia and Europe, and less frequently in Africa and America.

The sign has no uniform function and meaning. In Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, the swastika is still used today as a religious symbol of luck. In German, a heraldic sign similar to the swastika has been called the "swastika" since the 18th century.

In the 19th century, ethnologists discovered the swastika in various cultures of antiquity. Some transfigured it into the sign of an alleged Indo-Germanic race of "Aryans". The German völkisch movement interpreted the swastika in anti-Semitic and racist terms. Subsequently, the National Socialists made a swastika angled to the right and inclined at 45 degrees the emblem of the NSDAP in 1920 and the central component of the flag of the German Reich in 1935.

Because the swastika represents the ideology, tyranny and crimes of National Socialism, the political use of swastika-shaped symbols has been prohibited in Germany, Austria and other countries since 1945. In Germany, swastikas may only be displayed for "civic education" and similar purposes according to § 86 paragraph 3 StGB.

A Hindu form

NSDAP party badge (banned in some states)

Legal

→ Main article: Use of symbols of unconstitutional organisations

On August 30, 1945, the Allied Control Council banned all Germans from "wearing any military rank insignia, medals, or other insignia." The ban also included Nazi swastikas. It remained in force in the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR until 1955. On October 10, 1945, the Control Council banned the NSDAP, all its branches and affiliated associations, and their symbols. In the Nuremberg Trials of 1946, the NSDAP and all its subdivisions were declared a "criminal organization". Thus, their symbols were also banned.

In the Federal Republic, pursuant to Article 139 of the Basic Law, all Allied laws on the "liberation of the German people from National Socialism and militarism" initially continued to apply. They were replaced by the inclusion of the offences of treason against the peace, high treason and endangering the democratic constitutional state (§ 80 to § 92b) in the Criminal Code. Within this framework, section 86a threatens the public "use of signs of unconstitutional organisations" for the purpose of their dissemination with up to three years' imprisonment or a fine. Paragraph 3 exempts representations of these signs that serve "civic education, the defence against unconstitutional endeavours, art or science, research or teaching, the reporting of contemporary events or history or similar purposes".

The Federal Supreme Court clarified the scope of § 86a StGB in test cases. Since 1973, the ban has included swastikas on war toys and original models of weapons from the Nazi era. However, swastikas that do not objectively advocate National Socialism were later permitted:

- in works of art, for example political cartoons,

- in auction catalogues,

- for religious practice, including the Falun Gong in Germany,

- as anti-Nazi symbols by anti-fascist groups to reject right-wing extremist organisations and ideologies. In doing so, the Federal Court of Justice overturned previous rulings against users of anti-Nazi symbols in 2007.

According to current legal opinion, § 86 StGB also prohibits symbols altered by neo-Nazis, some of them such as Odalrune, Triskele and Schwarze Sonne, however, only as logos of banned organisations, not in general. The private removal of illegal swastikas from the property of third parties, for example by painting over, scratching off or pasting over, is usually considered damage to property.

In Austria, the Verbotsgesetz (Prohibition Act) of 1947 regulates the handling of National Socialist organisations, ideas and their symbolism and punishes their misuse.

On Germany's initiative, the European Parliament proposed a Europe-wide ban on the swastika in 2005. The occasion was a photograph of the British Prince Harry in a Nazi uniform with a swastika armband, which he had worn at a private costume party on 14 January 2005. In Britain, the Hindu Forum, which represents some 700,000 Hindus, demonstrated against the ban. In January 2007, Germany withdrew its push. The European Union rejected the ban in April 2007. A consensus on the ban was prevented above all by Great Britain and Denmark, with their traditionally broad view of freedom of opinion, as well as Lithuania, which also wanted to ban symbols of Stalinism.

In 2013, the Constitutional Court of Hungary lifted a ban on symbols of "arbitrary rule" (red star and swastika) that had existed there since 1993: The ban was to be re-regulated by law. Latvia, on the other hand, banned these two symbols.

In the USA, renowned constitutional and international law experts are arguing for a general ban on neo-Nazis displaying the swastika because it is historically singularly charged, calls for genocide and promotes the destruction of a group. This is not political speech worthy of protection, but incitement to sedition and disturbance of public order.

Swastika in the prohibition sign

Archaeological Findings

·

zoomorphic nephrite amulet from Kardzhali, Bulgaria, ≈6000 BC.

·

reconstructed bowl from Samarra, about 4000 B.C.

·

Seal from Harappa, about 3000 BC.

Asia

At Tell es-Sultan near Jericho, a preceramic stamp with a round stamp face was found engraved with a symmetrical swastika. It is dated to 7000 BC. Similar swastika motifs were found on a pendant from the Tappa Gaura in Iraq (before 4000 BC) and on a seal at Byblos (c. 3500-3000 BC).

On Samarra ware (c. 5000-3000 BC) from present-day Iraq, swastikas were found, individually or as part of an ornamental composition, combined with images of plants, animals and humans. One bowl shows in the centre a sign of the cross with four arms bent at right angles, surrounded by images of five scorpions. It is dated to 5500 BC.

In the Indus culture, the swastika has been attested since about 3000 BC. The oldest known examples are seals or stamps found in 1924 at the villages of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa in what is now Pakistan. They show right- and left-angled swastikas. Thus, the swastika was common in India about 1000 years before the spread of "Aryan" speaking tribes.

Decorative swastikas on clay vessels were found in Baluchistan and Susa in the 1930s. They are dated to about 3000 BC.

Eastern Europe

Six Venus figurines carved from mammoth ivory and several bracelets engraved with various lines and geometric shapes were found at the Mesyn archaeological site in Ukraine. They are dated to about 15,000 BC and are assigned to the Eastern European Epigravettian (Upper Paleolithic) period. One of these figures bears a cross sign formed from parallel meandering lines with four curled arms bent at right angles several times. The same motif is engraved on one of the bracelets. These are the oldest known swastika depictions. The researcher Karl von den Steinen (Prehistoric Signs and Ornaments, 1896) interpreted them as a stylized image of a bird, especially the stork, and thus as a symbol of fertility, life, spring and light.

Some ceramic fragments of the Neolithic Vinča culture (distribution area in present-day Bulgaria, Romania and Serbia) are painted with a swastika made of white humus paint. They are dated to the 6th millennium BC and are considered to be a decorative element representing the power and movement of the sun.

Mediterranean

·

Minoan vase from Crete, Iraklio Archaeological Museum

·

Terracotta balls from Troy after sketches by Schliemann, ~1300 BC.

·

Vase painting of the geometric period, Kantharos, ~780 BC.

·

Silver coins from Corinth, ~550-500 BC.

·

Soldier's helmets, ~350 BC.

The Minoan culture on Crete (from about 2600 BC) left behind vases, some of which are painted with individual swastikas. Greek vase painting of the geometric period continued this ornamentation. Here, both left-angled and right-angled swastikas occur. They are close in development to the meander pattern. Both ornaments are probably abstract images of natural forms, for example from the plant world. In the partly Greek-influenced local art of Apulia of the 7th to 5th century BC, swastikas are common. Since the time of Alexander, they also appear on soldiers' helmets.

Starting in 1870, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann found swastikas on everyday objects, such as pottery, hand spindles and terracotta, on the hill of Hissarlik (Troy, Turkey). Their classification and dating are controversial. Today they are assigned to younger excavation layers (VII to IX, from about 1300 BC).

·

Urn of the Villanova culture

·

Etruscan gold pendant, Bolsena, ~700-650 BC.

In the Villanova culture (~1000 BC), funerary urns with geometric patterns were found, including swastikas with multiple bent ends and wavy bands. The Etruscans (~900-260 BC) and the Faliscans continued the use of the symbols.

·

Roman floor mosaic in Pula, Istria, ~1st century BC.

·

Floor mosaic in a bath from Herculaneum, before 79

·

Brick stamp from Vicus Mülfort, ~200

·

Floor mosaic in the House of Dionysus in Paphos (Cyprus), ~200-300

·

Contiomagus, floor of the Villa Hylborn

In the Roman Empire, the swastika is usually found as one of many varied, repeated and complexly interlaced formal elements of meander ornamentation. Swastika patterns are often part of floor and wall mosaics made of tessera, of frescoes or stucco. Such floor mosaics were created from the Hellenistic period onwards (from about 300 BC) throughout the Roman Empire, including in Roman-occupied Syria-Palestine. They were found there, for example, in a synagogue at En Gedi from the Hasmonean period, in the antechamber of a villa at Masada, in a reception room of the palace at Caesarea Maritima, and in the vestibule of a villa in the upper city of Jerusalem. They belonged to the general splendor and geometric aesthetics of architecture of that time, but not to those specific patterns by which buildings used by Judaism or later by Christianity can be distinguished.

Roman swastikas are also found on brooches (clasps for fastening garments), on three contorniates, pieces of clothing, a Mithras monument and Christian funerary inscriptions. They are interpreted as decoration and apotropaic (evil-preventing) or magical signs of protection.

Central and Northern Europe

A megalithic rock at Ilkley Moor (West Yorkshire, England), called the Swastika Stone, is engraved with a serpentine, serpentine meandering line with nine circular depressions enclosing a four-part Swastika-like figure. Some assign it to the spiral cup-and-ring markings of the Stonehenge culture in the area and date it to about 3300 BC, while others assign it to the Celts and date it to the Late Bronze Age (≈1600-1100 BC). Similar patterns have been found on Scandinavian metal vessels of that period and on vessels of the Mycenaean culture.

A board-woven border from the Celtic grave at Hochdorf an der Enz dating from the Hallstatt period (≈500-450 BC) bears a series of swastikas. Whether the bearers of the Hallstatt culture can be equated with the Celts is still disputed in research. Their strictly geometric forms were followed by the sinuous, intricate style of the Latène period (≈450 BC to the turn of the century). This explains to some why swastikas were very rarely found among the Celts. Like the wheel cross, the "Celtic cross" and the triskele, they are interpreted as power signs with a magical connection to the cult of the dead. From various, often colourful representations on everyday objects, such as clothing fabrics, it is concluded that the swastika had no specific symbolic meaning among the Celts.

·

Brooch, Bronze Age (Museum Laureacum, Austria)

·

Spear blade of Dahmsdorf with swastika (right) and runes, ≈250

·

Leg comb from the Nydam Moor, 3rd/4th century

· _from_Værløse,_Zealand,_Denmark_(DR_EM85;123).jpg)

Brooch with runic inscription, ≈300 (Værløse, Denmark)

·

Djupbrunn's C-Bracteate-II (IK 44) 5th century, Gotland

·

Urn, North Elham, ≈5th/6th c.

· _(cropped).jpg)

Anglo-Saxon disc brooch of the 6th/7th century, York.

In the Bronze Age in Central and Northern Europe, swastika-like signs had four arms bent in the same direction and shaped like a spiral. Since the Early Bronze Age they appear as ornaments on everyday objects, especially on jewellery, as well as on Scandinavian rock paintings of the Nordic Bronze Age. These motifs are found continuously from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Middle Ages on various carrier objects. From this, researchers conclude that they generally had an ornamental function with possibly apotropaic significance.

The various groups described as Germanic used the swastika as a stylistic element in their everyday culture from the Roman Imperial period (RKZ) through the Migration Period (VWZ) and the Early Middle Ages to the Viking Age. It occurs in the RCC as a stylized motif on urns in cremation burials north of the Alps, for example on isolated "bowl urns" of the Elbe Germanic tribes of the 3rd or 4th century, which were set into the moist clay as decorative bands using the rolling wheel technique. It also occurs as engravings on weapons, such as the "spear blade of Dahmsdorf" (found 1865). Similar, partly older spear blades were found at Kowel (Ukraine), Gotland (Sweden), Rozwadow (Poland), Øvre Stabu (Norway) and Vimose (Denmark). According to Rolf Hachmann, these swastics are related to "tamga" (seals, stamps) of the Sarmatians (Iran).

Brooches are also bearers of swastika motifs. On Zealand (Denmark) (11), in the rest of Denmark (3), in Norway (3), Finland (2), southern Sweden (1) and Mecklenburg (1) a number of similar swastic brooches were found, riveted from a round bronze plate with ornaments pressed from silver sheet on it, four curved arms and small plates at the end. Similar brooches found in Hungary have animal heads at the end of the arms. Together they are traced back to older Roman brooches and dated to 250 to 400 AD.

VWZ gold bracteates from centres of wealth in present-day Denmark contain swastikas alongside other symbols and script-like signs in certain "form families" listed in the "Iconographic Catalogue" (IK). For example, the B-bracteate from Großfahner, district of Gotha (IK 259) shows a figure raising its empty hands, above which are a swastika and a triskele. IK 389 shows a swastika with triskele, cross and other symbols. In the younger RKZ and VWZ such swastikas appear together with runes, especially on brooches and bracteates. On the model-like form families of the B-bracteates from Nebenstedt (II), Darum (IV) (IK 129,1; 129,2), Allesø, Bolbro (I), Vedby (IK 13,1-3) a swastika is found as an insertion in the magic runic word laukaR ("leek"). In the left-hand runic inscription of Nebenstedt and Darum, a swastika appears as a sign with an undetermined function. Such swastikas between runes were interpreted partly as special characters, partly as symbols, which were supposed to reinforce a magical power of the runic statement.

For example, a swastika on the rune stone of Snoldelev in Denmark belongs to the Viking Age.

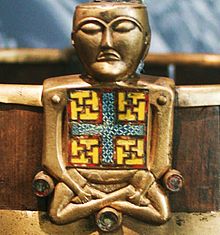

Among the grave goods in the Oseberg ship (c. 830), a small bucket with two bronze handles was found in 1904. Both show an identical human figure with closed eyes sitting in the lotus position, bearing a blue enamelled cross and four red swastikas on a yellow ground on the chest. They are alternately angled to the right and left, filling the open spaces around the cross to form a square. Although the figure is reminiscent of a meditating Buddha figure that Vikings may have encountered on their trade routes, this example is more likely to be interpreted as loot from Ireland due to very similar shaped and coloured handles of Celtic hanging vessels.

Swastikas of Germanic cultures are still interpreted differently today. Christian Jürgensen Thomsen and Oscar Montelius interpreted them as "signs of Thor" based on bracteates in 1855. This was encouraged by findings of similar signs called þórshamarr in Iceland in the 16th century, which suggested a relationship with the Mjölnir (Thor's hammer). The Swedish archaeologist Carl Bernhard Salin, on the other hand, disputed this attribution, arguing that these bracteates could just as easily be attributed to the deity Odin because of other features. Karl Hauck also associates the swastikas on bracteates with Thor or Odin. The linguist Wolfgang Meid, on the other hand, sees no linguistic evidence for a religious-cultic use of the symbol.

·

Sun cross (Lauburu) at the baptismal font of the parish church Labach

·

St. Marineh Church, Armenia, 11th-13th c.

In the Middle Ages in Europe, Roman and Germanic swastikas were often related to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ or his majesty as the "light of the world". They appear on frescoes and stone slabs of church buildings, associated with the meander line, in Romanesque ornamentation and some Gothic buildings. They were considered "protective means against the devil".

Africa

·

Gold weight of Ashanti, Ghana, ≈1300

· .jpg)

Window of the Beta Maryam Church, Lalibela, 12th century.

Swastika ornaments from the Aegean reached the Middle Pharaonic Empire (2137 to 1781 BC) through trade and became popular from 1000 BC, especially in Nubia. South of the Sahara, however, few swastikas have been found. In 1898, the German explorers Leo Frobenius and Felix von Luschan attested them as engravings on coins or weights of the Ashanti in Ghana, as tattoos of a woman in Barundi (Uganda) or as amulets. They disputed the origin of these ornaments from the Mediterranean region and assumed an independent origin.

In the rock churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia (built around 1200) one finds many swastikas in floor mosaics, wall and column decorations. Some have curved arms and therefore cannot be derived from Indian or Roman models.

America

·

Pictograms, Zion National Park, Utah

·

Thunderbirds (Mississippi Culture)

·

Turtle shell (Mississippi culture)

·

Sicán jug, Huaca-Rajada, Peru

Some indigenous peoples of the Americas have also long decorated utilitarian objects with swastikas. The Navajo wove them into the patterns of the blankets, jackets and rugs they traded in. Other tribes also adopted this custom for their pottery. They saw the swastika as a representation of the rotation of the constellation Great Bear around the North Star and a symbol of a mythical prehistory: in it, four chiefs had been sent to each cardinal direction to find a better form of government than their own. For the Hopi, the migratory and return paths of their ancestors formed a large swastika, which corresponded to the movement of the earth on the right and that of the sun on the left.

The Anasazi in the southwest of today's USA drew pictures with swastikas in the antelope ruins. They are considered the oldest examples in North America. Also among rock drawings of the Hohokam culture in southern Arizona (300-1500) were dozens of swastikas, on their own or connected with other drawings. They are interpreted as decoration, not religious symbol. In the Mississippi River Delta, uniformly stylized cross-tribal colored patterns, including swastikas integrated into solar circles, were found on 13th century ceramics.

In one of the pyramids of Túcume of the early Sicán culture from the Lambayeque period in Peru (≈750-1375), a clay jar with a swastika drawn with charcoal was found.

Rock relief (swastika?) at Ilkley, ≈3300 BC.

Handle of a bucket from the Oseberg ship, presumed Celtic origin, undated

Search within the encyclopedia