Battle of Poitiers

Battle of Poitiers

Part of: Hundred Years War

.jpg)

Depiction of the Battle of Maupertuis around 1400

Battles of the

Hundred Years War

(1337-1453)

Phase 1 1337-1386

Channel and Flanders (1337-1340): Cadzand - Arnemuiden - Channel - Sluis

Chevauchées of the 1340s: Saint-Omer - Auberoche

Edward III campaign (1346/47): Caen - Blanchetaque - Crécy - Calais

War of the Breton Succession (1341-1364): Champtoceaux - Brest - Morlaix - Saint-Pol-de-Léon - La Roche-Derrien - Tournament of the Thirty - Mauron - Auray.

France's Allies: Neville's Cross - Les Espagnols sur Mer - Brignais

Chevauchées of the 1350s: Poitiers

Castilian Civil War & War of the Two Peter (1351-1375): Barcelona - Araviana - Nájera - Montiel

French counter-offensive: La Rochelle - Gravesend

Wars between Portugal and Castile(1369-1385): Lisbon - Saltés - Lisbon - Aljubarrota

2nd phase 1415-1435

Henry V campaign (1415): Harfleur - Azincourt

Battle for Northern France: Rouen - Baugé - Meaux - Cravant - La Brossinière - Verneuil

Joan of Arc and the turn of the war: Orléans - Battle of the Herrings - Jargeau - Meung-sur-Loire - Beaugency - Patay - Compiègne - Gerberoy

Phase 3 1436-1453

French victory: Formigny - Castillon

The Battle of Poitiers on 19 September 1356 (in German-speaking countries also known as the Battle of Maupertuis) was an event of the Hundred Years' War in which the French king John II fell into English captivity. It was - after the ill-fated Battle of Crécy (1346) for the French - the second of three major English victories in the war, and in a sense a repeat of Crécy, as it again demonstrated that better strategy and tactics could outweigh numerical inferiority.

After their victory at Crécy, the English had firmly established themselves in Guyenne, from where they launched regular raids into the south of France. In 1355, King John II, who had succeeded his father Philip VI, who had died of the plague, on the throne in 1350, had already failed to defeat them for lack of reserves, so that the "Black Prince" Edward of Woodstock was able to plunder the county of Quercy almost unhindered. In 1356, John II called together the Estates-General (États généraux), which granted him the necessary funds to raise an army (30,000 men over 5 years).

Operations before the battle

The Chevauchée, led by the Black Prince Edward of Woodstock, had taken the English from Gascony to Bourges by way of Bellac and Issoudun, which was taken by storm, while the French were still engaged in the siege of Breteuil in Normandy. Meanwhile, on the English side, the Duke of Lancaster had set out from Brittany to join the army of the Black Prince. The latter intended to meet him by way of Tours, but a hailstorm and lack of siege equipment prevented the capture of the city, and as John II. had meanwhile collected a large army at Chartres and started in the direction of the Loire, Edward was compelled to move back into Gascony. A union with Lancaster's forces did not succeed, as the latter could not find a passage across the Loire, and was thus trapped in Brittany. In order to pursue the enemy more effectively, John II left half of his army behind with, among other things, the burghers' fighting men, and confined himself to the cavalry, with which he hoped to make more rapid progress. When he had placed the enemy, the French army was south of Poitiers, and the English, laden with booty, was on its way back to Bordeaux. Since the way into the Guyenne was barred to them, the English, after prolonged negotiations, were forced to enter the fight.

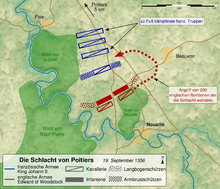

The battle

As at Crécy, the French were clearly numerically superior and had a force about twice the size of the English. The battlefield at Nouaillé-Maupertuis was an uneven terrain interspersed with hedgerows, so John II decided to take the fight on foot, while the English used the hedgerows to position their archers behind. On the French side, the Maréchal Clermont advocated cautious tactics aimed at starving out the English, who were struggling with supply difficulties. Others, including the Earl of Douglas, who led a Scottish relief contingent, the Bishop of Châlons, and Arnoul d'Audrehem, argued against an attack. Early in the morning movements on the English left wing under the Earl of Warwick made it appear that they were trying to get their spoils across a ford to the other side of the Miosson. Before the French could deploy in an orderly fashion, the French right wing under d'Audrehem, assuming that the English were fleeing, now forced their way into a hedge-lined path (Maupertuis means bad passage), thus becoming easy prey for the English archers, and d'Audrehem fell into captivity.

Meanwhile, on the French left wing, Clermont, after the advance of the right wing, was forced to attack as well in order to maintain a halfway closed line of battle. He was opposed by the English right wing under the Earl of Salisbury, who had reserve troops from the Earl of Suffolk rushing to his aid. Clermont was killed in this fighting, and in the face of fierce opposition, especially from the archers, the French were forced to retreat. Now the second line of the French under the Dauphin rushed forward, but was also unsuccessful. A third wave under the Duke of Orleans got into the retreating troops of the Dauphin, which led to some confusion, whereupon the king, whose own divisions had hitherto remained in the rear, now threw them into the battle and tried to force the decision. His attack was directed against the centre of the enemy's ranks, where the Black Prince stood with his troops. The latter then ordered Jean III de Grailly with a contingent of horsemen on his right wing to make a sweeping attack, which remained undetected by the French through a hill and led behind the French ranks. As at the same time on the English left wing the archers of the Earl of Oxford succeeded in attacking the French right wing from the side, the French were put on the defensive. The battle turned in favor of the Black Prince. John II, fearing defeat, had his sons brought to safety at Chauvigny: the heir to the throne Charles, the Duke of Normandy and the Duke of Anjou. When his army saw this, they took it as a sign of defeat and turned to flee.

John II refused to flee and soon found himself isolated with his 14-year-old son Philip (later Duke Philip the Bold of Burgundy). The two were surrounded and captured and the Oriflamme banner also fell into the hands of the English. Two miles away stood the new castle of Camboniac, the Château de Chambonneau, which the Black Prince had previously taken by deception. The two prisoners were taken first here and then to Bordeaux.

Map of the course of the battle

Search within the encyclopedia