Battle of Dien Bien Phu

Battle of Điện Biên Phủ.

Part of: Indochina War

French infantrymen in their trenches at Điện Biên Phủ.

Indochina War 1946-54

Haiphong - Hanoi - Papillon - Léa - Ceinture - Route Coloniale 4 - Vĩnh Yên - Mạo Khê - Sông Đáy - Hòa Bình - Nghia Lo - Lorraine - Nà Sản - Brittany - Adolphe - Laos I - Atlante - Camargue - Hirondelle - Brochet - Mouette - Laos II - Điện Biên Phủ - Mang-Yang Pass

The Battle of Điện Biên Phủ is considered the decisive battle of the French Indochina War between the forces of France, including the Foreign Legion, and the troops of the Vietnamese independence movement ViệtMinh. The battle for the French stronghold in Điện Biện County near the then county seat of Điện Biên Phủ began on 13 March 1954 and ended on 8 May with the defeat of the French, sealing the end of the French colonial empire in Indochina (formerly French Indochina, now Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia). The Việt Minh managed to establish the necessary logistics for artillery superiority over the French, who were supplied from the air, primarily through manpower. This enabled them to cut off most of the air supply to the French, who had not expected such a feat from their opponents, and after a few months they were able to capture the fortifications around Điện Biên Phủ. A large proportion of the soldiers taken prisoner died in the custody of the Việt Minh.

The outcome of the battle led to the fall of Joseph Laniel's government in France and paved the way for the negotiated settlement of the conflict, the partition of Vietnam and the end of French Indochina at the Indochina Conference.

Previous story

Background

Indochina was a French colony until the beginning of the Second World War. With the defeat of 1940 and the strengthening of the Axis powers, the colony fell under the sphere of influence of Japan. This influence weakened the French position of power to such an extent that the ViệtMinh were able to form as a mass political and military movement with the goal of national independence as the politically strongest force. This National Independence League, formally non-partisan but actually under communist control, was able to establish the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as a sovereign state of communist character in the August Revolution in the northern part of the country in 1945. However, the French colonial power attempted to draw the communist Vietnamese state into a military conflict and thereby restore the colonial order by means of military superiority. Politically, the French sought to establish the Republic of Cochinchina as a partially sovereign client state in order to create a non-communist Vietnamese state and deprive the North of legitimacy. The Việt Minh responded with a guerrilla campaign in the South. With the bombing of the North Vietnamese port city of Haiphong by the French, the Indochina War began on 23 November 1946. The first year's fighting ended in the expulsion of the Việt Minh organisations into hiding and the re-establishment of the colonial regime. However, the Việt Minh continued to exist as a tightly organised guerrilla movement, starting from their bases in northern Tonkin.

Since mid-1950, the Việt Minh were able to bring their own forces close to the equipment and firepower of a regular army through Chinese support. The Việt Minh fought in large units with supporting artillery. In Tonking, several offensives managed to push back the control of French forces to the Red River delta. The changing French governments accepted the simmering conflict without resolving it decisively. By the early 1950s, the majority of the French political leadership believed that a military victory against the Việt Minh was unrealistic. Likewise, the possibility - Pierre Mendès France had been raising it publicly since 1950 - of a diplomatic solution and withdrawal from Indochina had been discussed for some time. The emerging peace in the Korean War, which ended in partition, encouraged the pursuit of a negotiated settlement. In 1953, Prime Minister René Mayer appointed General Henri Navarre as the new commander-in-chief in Indochina. Navarre was instructed to establish as strong a military position as possible as a bargaining chip for planned negotiations.

Through the conspiratorial political work of the Việt-Minh cadres, a large part of the rural population was covered by covert Việt-Minh organisations in the villages, paying levies and providing recruits. Even in the Red River Delta, which was actually controlled by French colonial troops, some 70% of the villages were politically in the hands of the independence movement. In 1953, 75,000 regular French soldiers were in supra-regional mobile units. Another 75,000 were assigned to some territory as regional troops. Some 200,000 local troops formed the backbone of the guerrillas on the opposite side. In contrast, there were a total of around 400,000 soldiers of the colonial power - albeit of quite different composition. The majority were locally recruited colonial troops. The French forces had to evacuate large parts of northern and central Vietnam under pressure from the Việt-Minh guerrillas. By 1953, only the coastal regions around Hanoi, Hue, and Saigon were left without a palpable guerrilla presence. Instead of a losing attempt to control the country's rural areas, the French leadership wanted to inflict decisive losses on the Việt Minh in a conventional decisive battle. This was to be done by building a fortress-like ground base supplied from the air, which would then be successfully defended in an open battle.

Operation Castor

The French military leadership under General Henri Navarre wanted to give the war a decisive turn by destroying the Việt-Minh troops. To achieve this, the guerrilla units were to be lured into an open battle. To this end, an air-supplied outpost was to be established in northwestern Tonking to attract Việt Minh attacks. The model was the air supply of light infantry forces of the Chindits during the Burma campaign in World War II, as well as the defence of Nà Sản in 1952, where French troops had successfully defended a circular range of hills supplied by the centrally located and thus screened airfield. Navarre assigned two tasks to the sparse air forces: on the one hand, they were to supply and support the garrison, and on the other hand, they were also to disrupt the Việt Minh's supply routes to the site of the battle.

The choice fell on the outpost at Điện Biên Phủ, which had already been abandoned several times and was occupied at the time by a locally raised battalion of the Independent Infantry Regiment 148 of the Việt Minh. Unlike Nà Sản, however, the base was located in a valley and surrounded by high ground that was supposed to be outside the French defences. Once successfully established and defended, the base was to serve as a patrol base to control the surrounding highlands. In doing so, Điện Biên Phủ was also to serve as a base of operations and retreat for pro-French partisans of the Thái and Hmong ethnic minorities. From a base permanently held in the highlands, the French leadership hoped to control the region's rice and especially opium crops. On 17 November 1953, Henri Navarre ordered the reoccupation of Điện Biên Phủs from the air. This was done under formal protest from the Air Force's transport chief in Indochina Jean-Louis Nicot, who judged the available forces to be too small to supply the isolated base. Navarre deliberately issued the order a day before Admiral Georges Cabanier arrived to deliver government instructions to him to refrain from offensive operations for the time being for political and economic reasons. From 20 to 23 November, 2200 French paratroopers landed at Điện Biên Phủ. They quickly succeeded in driving the sparse Việt-Minh forces from the landing site and establishing field fortifications. Navarre, in a secret order to René Cogny, commander-in-chief of Tonkin, on 3 December 1953, reiterated his intention to prepare Điện Biên Phủ as the site of a defensive battle. This was to inflict heavy losses on the Việt Minh.

Construction of the Điện Biên Phủ base.

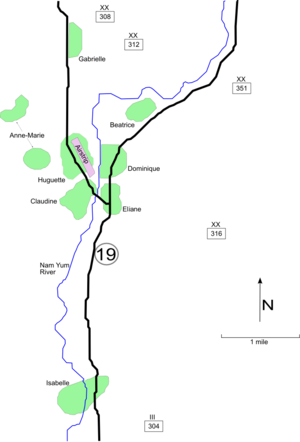

The development of Điện Biên Phủs into a fortified base was begun immediately after the landing. The French leadership entrusted Colonel Christian Marie de Castries with the supreme command and planning of the entire defensive installation. The valley, which was about 15 kilometres long and about five kilometres wide, was to be secured by fortified bases. These were to be positioned so that they could support each other with fire, reinforcements and counterattacks. The bases were each manned by a battalion. A typical base consisted of a continuous trench system secured with minefields and barbed wire. Fortified blockhouses made of sandbags and wood were built at convenient locations. These were manned by heavy machine guns. 130 tons of timber and 20 tons of scrap iron were flown in for construction. 2200 tons of wood could be cut on the spot. According to the calculations of the commander of the 31st Engineer Battalion André Sudrat, who took part in the battle, there was a need for 34,000 tons of building material to build fortifications secured against heavy artillery on the entire base. This quantity was impossible to procure with the available airlift capacity. The central bases of Dominique and Eliane were conveniently located on a hilltop and were favored for fortification. Bases Anne-Marie, Claudine, and Huguette, to the west, were on flat terrain. At the entrances to the valley in the northwest and northeast, the bases Gabrielle and Béatrice were built. Béatrice also had an advantageous elevation. Isolated in the south was the base Isabelle. Here a small part of the artillery was placed for defense. A second airfield was to be built at this base. In the center was the majority of the French artillery, the main airfield, a field hospital and a water treatment plant. The artillery consisted of 24 105-mm howitzers, 28 120-mm mortars, and four M45 quadmount anti-aircraft guns. Likewise, ten M24 Chaffee light tanks had been flown in. In order to develop sufficient firepower with the available number of guns, the gun emplacements were built open to the top to permit rapid reorientation of the artillery. For the same firepower from fortified positions with a restricted firing range, about twice as many guns would have been necessary.

Preparations for the Việt Minh attack

In January 1953, the plenum of the Communist Party of Vietnam had agreed to attack only the weak points of the enemy due to the military superiority of the colonial power. Attacking well-defended areas was considered too costly in terms of losses. Therefore, the French forces were to be dispersed by actions in the periphery. The dispersed units were then to be destroyed by locally superior forces. Vietnamese commander General Võ Nguyên Giáp toyed with the idea of an offensive in the Red River delta, but like Hồ Chí Minh, he concluded that it would be too risky. The Chinese military advisers around Giáp were equally in favour of shifting operations to the periphery. The reoccupation of Điện Biên Phủs by colonial forces came as a surprise to the Vietnamese leadership. In October 1953, Giáp, Hồ and other high-ranking cadres met in Thái Nguyên province. The Vietnamese leadership agreed to shift their focus to the northwest of the country. In December 1953, Giáp presented a plan to the Party Politburo to first encircle and then completely capture the enemy base at Điện Biên Phủ with a major offensive. On December 6, 1953, the Politburo approved Giáp's plan. Hồ, however, gave Giáp explicit instructions to refrain from attacking at his own discretion if victory could not be assumed as certain.

As early as the beginning of December 1953, mostly regular Việt-Minh forces controlled the outskirts of Điện Biên Phủ in the north and northeast and engaged in needle-stick battles. Among others, de Castrie's chief of staff was killed by a sniper. The French attempt to evacuate 2100 pro-French Thái partisans from the neighbouring province of Lai Châu by land to Điện Biên Phủ failed with 90% casualties. An attempt to support the fugitives with forces from Điện Biên Phủ failed after a few kilometres of advance due to Việt Minh resistance. An expedition of small detachments to Laos and meeting with pro-French troops under Colonel Crèvecœur was presented by de Castries to the media in a propaganda-like manner by taking journalists, but was militarily fruitless. The French military was correctly in the picture by the end of 1953 about the number of forces planned for the attack and the bringing in of artillery. Navarre informed U.S. Ambassador Donald R. Heath at the turn of the year of his doubts that Điện Biên Phủ could be held. However, De Castries and also his artillery commander Charles Piroth remained confident that they could successfully defend the base.

The battle plan proposed by Giáp in December envisaged a three-phase course of action. First, the isolated bases of Béatrice, Anne-Marie and Gabrielle were to be taken. In the second phase, positions were to be driven up to the remaining bases, then captured in the third phase. The plan called for the deployment of nine infantry regiments with the support of all available artillery, engineer, and anti-aircraft units of the Việt Minh. These combat units together comprised about 35,000 men. In addition, there were 1720 soldiers to secure the supply routes and 1850 men to man the headquarters, including a reserve of 4000 fresh recruits. This brought the total number to 42,570 military personnel. To these were added some 14,500 civilians to serve as porters directly with the combat units. Giáp planned for a forty-five day battle. For this he calculated 300 tons of ammunition, 4200 tons of rice, and 212 tons of meat, vegetables, and sugar. The number of civilians employed in the rear is not precisely known, but is estimated at about 200,000. In this regard, a land reform carried out in 1953 in the areas controlled by the Việt Minh increased the will of the population to cooperate. The Việt Minh had around 600 Soviet-designed trucks at their disposal. For transportation purposes, unasphalted jungle roads were constructed in Điện Biên Phủs hinterland towards the Chinese border. In this process, individual vehicles were usually assigned to the same stage. Waterways were also used with rafts and traditional river boats. Traffic routes were shielded from aircraft by camouflage measures and an observer service. The network of routes was laid out in such a way that any routes lost to bombardment could be quickly compensated for by parallel routes. According to French military intelligence, the transport time of a load over the 800-kilometre route from the Chinese border was about a week. The Việt Minh's actual consumption for the entire operation was 16,800 tons of food, about 20,000 rounds of barrel artillery, about 2.5 million rounds of ammunition for automatic weapons, 30,000 rounds of 37-mm anti-aircraft ammunition and 90,000 hand grenades.

The French Air Force as well as units of the Naval Air Force operated intensively with their limited resources against the supply routes towards Điện Biên Phủ. In early 1954, food shortages were reported by Việt Minh soldiers. However, the air offensive against the supply routes failed due to the stealth measures and anti-aircraft artillery of the Việt Minh. The French lost several dozen aircraft each month. Nevertheless, the French troops around Điện Biên Phủ received sufficient supplies, mainly from the air, from February onwards. The actual plan called for an attack on 25 January. The French leadership was aware of the Việt Minh's intentions to attack. Giáp, however, initially postponed the attack indefinitely in order to prepare his troops on the ground for the attack and to establish positions, especially for artillery. Contrary to the initial objective of overrunning the base with rapidly approaching forces, a well-planned, methodical battle was to be fought. Giáp cited the arrival of French tanks and the stationing of Bearcat fighters on the airfield as the impetus for this decision.

The preparations dragged on for another six weeks. Particular attention was paid to the bulletproof sheltering of the artillery in casemates cut out of the rock. The Việt Minh also set up numerous gun emplacements to deflect French counterfire away from their guns and methodically prepared their crews to fire on their targets, most of which were permanently assigned. The Việt Minh set up their artillery on the side of the hills facing the French above Điện Biên Phủ. This allowed them to have their guns fire directly instead of by indirect fire. This increased the accuracy of hits by the gun crews, most of whom were relatively inexperienced. The French commanders at Điện Biên Phủ were convinced until the start of the battle that the Việt Minh would not succeed in exerting dangerous artillery superiority: Artillery Commander Piroth held that even if the Việt Minh managed to bring up heavy artillery, they would not be able to supply it adequately with ammunition. The deployment of artillery on the enemy-facing sides of the hills was dismissed by Piroth as a "rumour", although the daily LeMonde had already reported it in February.

In early March there was sporadic shelling of the airfield at Điện Biên Phủ. Sporadic shelling of the fortress itself had begun in late January. On 3 February, to mark the Tết Nguyên Đán, the Việt Minh shelled the French positions with an intense thirty-minute artillery bombardment. Similarly, there were coordinated Việt Minh sabotage and commando actions against French air force installations and aircraft throughout North Vietnam.

Schematic representation of the French positions

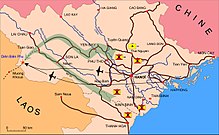

Location of Điện Biên Phủs in Vietnam, showing the French air supply routes as well as the Việt Minh approach and supply routes.

Military control of the territory during the Indochina War

Course of the battle

Beginning of the battle in March

In March 1954, Giáp judged his troops to be well enough prepared. The Việt Minh opened the attack on 13 March 1954 with artillery fire on the camp. The French artillery, despite mustering a quarter of its 105-mm ammunition, was unable to suppress the enemy artillery. As a result, the camp's main airfield was badly damaged and almost completely unusable by the first day of the battle. The secondary airfield at Isabelle was equally impossible to bring into service under these conditions. The combined action of artillery and infantry close to the French positions enabled the Việt Minh to overrun the Béatrice base after only a few hours. Only 250 out of 750 members of the battalion of the 13e DBLE defending the base were able to retreat. On 15 March, the Gabrielle base was taken. Of the defending Algerian infantrymen, 220 were taken prisoner of war. 550 were killed. That same day, artillery commander Piroth committed suicide, according to those around him due to guilt over the failure of his artillery to effectively engage the enemy's fire. De Castries tried to keep Piroth's suicide a secret in the camp. A few days later, however, the information was published in Le Monde. The Anne-Marie base fell to the Việt Minh on 17 March, after most of the defending Thái soldiers had retreated. The Việt Minh were thus able to successfully complete the first phase of their battle plan within a few days. Casualties were high, however, with 2500 combatants dead. In response to the start of the battle, the French government sent the country's highest-ranking active officer, General Paul Ély, to Washington to lobby for US support at government level. In Điện Biên Phủ itself, paratrooper officer Pierre Langlais, as chief of operations appointed by de Castries, took on more and more of the decisive role in commanding the battle.

The French government asked the United States for air strikes against Việt Minh forces at Điện Biên Phủ. The planning for this was code-named Operation Vulture. The Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, Nathan F. Twining, as well as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Arthur W. Radford, even presented an option for a use of tactical nuclear weapons. However, this option was rejected by the Eisenhower administration as well as Army Chief of Staff General Matthew Ridgway. The U.S. government nevertheless sought authorization for intervention from congressional leaders. Congress, however, demanded on the one hand the participation of the British as intervening allies and on the other hand the immediate full independence of Vietnam, since a commitment to French colonialism could not be justified on domestic political grounds. The British government under Winston Churchill rejected any intervention in Indochina. The French themselves saw the US demand for immediate state independence for the colony as unacceptable. As a result, there was no operational intervention by the U.S. or other Western powers on the side of the French. However, the rumour of an imminent air attack by the US Air Force was rampant in Điện Biên Phủ and was spread by officers to raise morale. The CIA-controlled Civil Air Transport company flew 682 transport missions over Điện Biên Phủ with the permission of the US government during the period between 13 March and 6 May 1954. During these missions, a C-119 Flying Boxcar was shot down over Laos. The two US crew members were killed.

Second wave of attack on the fortress

Due to the high losses of the first attack wave, Giáp announced a change in the attack tactics on the fortress on 18 March. In order to reduce their own losses, a system of trenches was to be driven as close as possible to the French positions before further attacks. To build the trenches, the troops brought in wood from the surrounding forests during the day. At night the positions were extended with simple tools. French artillery fire and air raids could not bring the construction of the positions to a standstill. Ambush counterattacks by the colonial troops failed with heavy losses in the fire of the guns and mortars of the Việt Minh. The Việt Minh also managed to keep the connection of the Isabelle base with the main camp under constant threat until the end of March. Opening the way for French troops required daily battles mostly with tank support. While the position was being expanded, Giap increased his reserves from about 8,000 to about 25,000 men.

On March 18, de Castries gave the order to bury the fallen on the spot of their death because of the danger of the transport. The French side tried to reinforce their fortifications with earth mounds for lack of better material. Extensive minefields were also laid. On the French side, the airlift to supply and reinforce Điện Biên Phủs came under increasing pressure from Việt Minh air defences. Nicot, the air force commander in charge, had ordered a higher drop altitude for supply drops. The airstrip was rarely successfully approached due to artillery fire from the Việt Minh. Few wounded were evacuated in the process. Reinforcements via landing aircraft were limited to medical personnel and medical supplies. The French military depended on supplies from US forces to maintain the airlift. Around 1000 cargo parachutes per day were needed to supply the troops from the air.

Giap opened the second wave of attacks on 30 March 1954. The targets of the offensive were the eastern bases of Dominique and Éliane and the base of Isabelle. The Việt Minh were able to capture parts of the Dominique and Éliane bases, but suffered heavy casualties under French bombardment and artillery fire. On the French side, there was fire from French paratroopers against fleeing Algerian colonial soldiers. The Vietnamese offensive failed to achieve its objective of completely capturing the bases. However, important hill positions were captured, which outnumbered the remaining French positions. On the French side, the second offensive led to a breakdown in morale, especially in North African and Vietnamese colonial units. Several thousand soldiers took shelter in natural recesses and caves of the Nam Youn riverbed and no longer participated in combat operations. The French leadership refrained from using armed force against the deserters, fearing negative effects on morale, especially among non-French soldiers. The French-controlled area was compressed by the attacks from about five square kilometers to about 2.6 square kilometers. However, the French artillery was still able to operate, although its operational capability dropped to around 50% in some batteries. The deployment of the Vietnamese artillery and its distribution in bulletproof casemates made it difficult for the Việt Minh to concentrate a large amount of fire on just one target. On 7 April, Giap again ordered trench warfare tactics without attacks over open ground to minimize friendly casualties. Around the same time, morale problems due to high casualties were reported to the leadership by political officers within the fighting forces. Giap and his staff responded with a political campaign against right-wing deviation, citing their own losses as undermining the morale of the soldiers.

The attempt to support the trapped troops from the direction of Laos with Hmong partisans and a small core of regular troops under the command of Colonel Boucher de Crèvecoeur failed until the end of April due to Việt Minh resistance. However, the rumour of this Operation Condor persisted both among the garrison of Điện Biên Phủ and in the French print media.

The case of Điện Biên Phủ.

By mid-April, the French garrison included 4900 fighting soldiers, some 4000 deserters and non-combatant personnel, and 2100 wounded. Although the Việt Minh gathered their forces for a new major attack and did not carry out any major assaults, the garrison lost 1430 soldiers by the end of April. Only 683 were brought in by parachute drop as "replacement reinforcements". The French air forces, with their few dozen bombers, were also unable to significantly disrupt the Việt Minh military structures, which were scattered over some 160 square kilometres and were mostly well camouflaged. Air force officers described the effectiveness of the bombing raids as low due to the pilots' lack of training. Giáp presented the plan for the complete capture of the French positions on 22 April. From 1 to 5 May, incursions into the Eliane and Huguette bases were to set the stage for a final general attack. This was to begin on 10 May 1954 after five days of preparation and only hesitant fighting on the part of the Việt Minh.

As the controlled territory became smaller and the threat of Việt Minh flak greater, French supplies dried up. The garrison had only three days' worth of food, two days' worth of light artillery ammunition and a few hours' worth of heavy artillery shells. On 30 April, French headquarters around General Ély considered for the first time ordering the breakout of several thousand men from the base to push several hundred kilometers through enemy-controlled jungle into French-controlled territory. The renewed general attack by the Việt Minh quickly achieved its limited objectives. De Castries was authorized to attempt a breakout on 2 May. However, in consensus with his subordinate commanders, he rejected this as futile. On 3 May he gave orders to send wounded still able to fight to the front.

On 6 May, the Việt Minh, having previously appeared to be easing their attacks, used Katyusha rocket launchers for the first time. This heavy artillery strike caused many deserters to flee from their caves on the Nam Youn River and led Giáp to believe that the collapse of the camp was imminent. As a result, three days before the scheduled date, Giáp ordered the general attack, which led to the collapse of French fighting morale during the day. In the engagement for the Éliane base, the Việt Minh used a mine to blow up part of the base's trench system. De Castries gave orders to cease all resistance, but was prevented by orders from formally surrendering with white flags by his superiors Navarre and Ély. The isolated base of Isabelle surrendered a few hours later in the early hours of 8 May 1954, with numerous native colonial soldiers divesting themselves of their uniforms and attempting in small groups to escape capture. On the same day, the previously scheduled Indochina Conference began in Geneva.

The Vietnamese flag flies over the French command bunker of Điện Biên Phủ.

French M24 tanks at the battle of Điện Biên Phủ.

First wave of the Việt Minh attack on the northern positions.

Search within the encyclopedia