Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg

Part of: War of Secession

Confederate soldiers taken prisoner (unknown photographer)

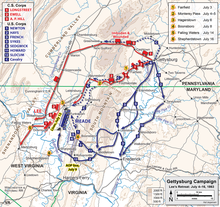

Gettysburg Campaign

Brandy Station - Winchester II - Aldie - Middleburg - Upperville - Hanover - Gettysburg - Hunterstown - Fairfield - Williamsport - Boonsboro - Manassas Gap

The Battle of Gettysburg took place from July 1 to July 3, 1863, near the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a few miles north of the Maryland border during the War of Secession. With more than 43,000 casualties, including over 5,700 killed, it was one of the bloodiest battles ever fought in the continental United States and is considered, along with Vicksburg and Chattanooga and alongside Antietam and Perryville in 1862 and the fall of Atlanta and Philip Sheridan's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, to be one of the decisive turning points of the American Civil War. The defeat of the Army of Northern Virginia under General Robert E. Lee ended the penultimate Confederate offensive in Union territory. The initiative thereafter passed essentially to the Union in the eastern theater of the war as well.

The three-day battle began on the first day with an encounter skirmish, which the Confederates won. The Northern Virginia Army attacked the Potomac Army on both wings the following day, but could not break through the Northern positions, so that day ended in a draw. General Lee attempted to force a decision on the third day with an attack on the center of the Army of the Potomac, but failed despite a temporary breach of the Northerners' positions. The offensive force of the Northern Virginia Army was thus exhausted.

Previous story

Objective

General Lee made a proposal to President Jefferson Davis after the victory at Chancellorsville to go north and invade Pennsylvania. This would allow the Northern Virginia Army to threaten the capital of Washington, D.C., as well as the cities of Baltimore and Philadelphia. The Army of the Potomac would thus be forced to follow Lee north. Major General Joseph Hooker, commander-in-chief of the Army of the Potomac, was to attack the Northern Virginia Army at a site chosen by Lee. Lee wanted to strike Hooker there again, but this time in Union territory. Other objectives were to prevent troops from the eastern theater of the war from reinforcing Ulysses S. Grant's siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and to get the Union to withdraw troops from the coastal areas of the Carolinas and Georgia. Lee rejected a reinforcement of General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Confederate Western Theater of War, to relieve Vicksburg, as well as the proposal to reinforce the Confederate Tennessee Army and crush the Union's Cumberland Army in Tennessee. The President and the Cabinet, with the exception of the Postmaster General, approved Lee's proposal, and even Lieutenant General James Longstreet, commanding general of the I Corps, accepted the plan.

Version

The Army of Northern Virginia marched north under cover of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The cavalry under Major General J.E.B. Stuart was to conceal the movement while reconnoitering the movements of the Army of the Potomac. At Brandy Station on June 9, the largest mounted battle in the continental United States occurred. Further engagements of cavalry followed at Aldie and Middleburg in Virginia. Stuart then skirted the Army of the Potomac to the east.

After the Second Battle of Winchester, Lee was able to cross the Potomac unmolested and advance to the Susquehanna. His army of about 75,000 men was spread out in a wide arc on both sides of South Mountain. The I Corps under James Longstreet had reached the Chambersburg area, the II Corps under Richard S. Ewell the area south of Carlisle, and the III Corps under Ambrose P. Hill the Cashtown area. Stuart's cavalry division was eastward of the Army of the Potomac, so Lee had no accurate information about the movements of the enemy army since June 24. When Lee learned from scouts in Longstreet's corps on June 28 that the Potomac Army had crossed the Potomac to the north, he ordered the Northern Virginia Army to assemble in the Cashtown area.

eve of battle

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln appointed Major General George Gordon Meade as commander-in-chief of the Army of the Potomac on June 28. Meade intended to place the Northern Virginia Army before it crossed the Susquehanna and to entice General Lee to attack the Potomac Army, which had reconnoitered defensive positions along Pipe Creek in northern Maryland. However, since Lee had abandoned his intention to cross the Susquehanna, Meade moved a corps to the Gettysburg area.

J. Johnston Pettigrew's brigade from Major General Henry Heth's division had approached Gettysburg on June 30 in search of rations and shoes. Already in the town, however, was Union cavalry under the command of Brigadier General John F. Buford. The latter was able to hold the town because Pettigrew did not accept the engagement and moved west.

Lieutenant General Hill ordered Heth for the next day to conduct a forcible reconnaissance against Gettysburg, assuming that the forces there were only Pennsylvanian militia. In doing so, Hill did not violate Lee's order not to engage in any major engagements until the Northern Virginia Army was assembled.

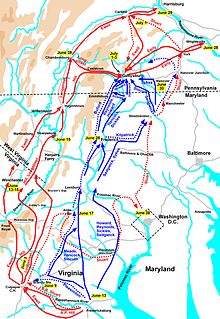

Gettysburg Campaign red: Confederate troops blue: Union troops

Course of the battle

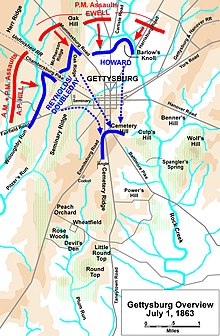

First day (1 July)

The brigades of Brigadier Generals James J. Archer and Joseph R. Davis - a nephew of the President of the Confederate States - reached the ridges fronting the town to the northwest about 07:30. Expecting little resistance, Heth deployed the two brigades on either side of Chambersburg Pike and marched toward the town. Brigadier General Buford, however, had not remained idle during the night, defending with the dismounted horsemen-armed with Sharps carbines-of his two brigades and a mounted artillery battery along McPherson Ridge. Buford succeeded in holding off the superior Southerners for more than two hours before he was forced to turn back to Gettysburg.

In these minutes the first two brigades of the 1st Division of the I Corps of the Army of the Potomac appeared and relieved Buford's cavalrymen. Commanding General Major General John F. Reynolds, on horseback, directed the brigade commanders to positions at McPherson Ridge and was mortally wounded. Earlier, Reynolds had still directed the commanding generals of the following corps, the XI and III, to reach the town with their troops in an accelerated manner.

The 1st Division of the I Corps, of which Major General Abner Doubleday had in the meantime assumed command, succeeded in holding off the Confederates, with heavy losses on both sides, until about 2:30 p.m. The Confederate army was still in its infancy. In the meantime, the First Brigades of the XI Corps, under Major General Oliver O. Howard, had reached Gettysburg and taken up positions on the right of the I Corps to the northwest and north.

By this time Heth had introduced the other two brigades of the division into the fray. This included the 26th North Carolina Regiment, the strongest of the Northern Virginia Army at 800 men, which numbered 212 men at the end of the first day and 80 heads at the end of the battle. Heth himself was shot in the head and remained unfit for duty for the rest of the battle. The division was taken over by Brigadier General Pettigrew.

Lieutenant General Hill, meanwhile, had introduced Major General William D. Pender's division into the fray, so that the Union I Corps had to move out across Seminary Ridge toward the city. Even before this attack began, the divisions of Majors General Robert E. Rodes and Jubal Early of the II Corps under Lieutenant General Ewell, coming from the north, had engaged the regiments of the I and XI Corps of the Potomac Army, which were still in position. Corps of the Army of the Potomac at Barlow Knoll.

When the Union positions finally collapsed to the north and west of the city, Major General Howard ordered the evasion to Cemetery Hill south of the city. There, upon reaching Gettysburg, he had already ordered Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr's division to hold that height at all costs. This made it possible to halt movements, some of which were escapes, and to reorganize the detachments.

Lee had reached the battlefield about 2:30 p.m. and recognized the defensive potential of the heights south of town for the Union. He therefore urged A.P. Hill to continue the previously successful attack, and ordered Ewell to take Cemetery Hill and Culps Hill "if practicable." Hill, however, could not continue the attack, as his troops had suffered heavy casualties and had little ammunition left. The Third Division of II Corps would not reach the area west of Gettysburg until evening.

Ewell did nothing to create the conditions for the attack. But without these conditions the storming of the two hills was just not practicable. Ewell conscientiously reviewed the "if practicable" order and decided that an attack was not possible, thereby forfeiting the opportunity to drive the Army of the Potomac from Culps and Cemetery Hill. Confusion among the Confederate leadership was also caused by alleged sightings of U.S. troops on York Pike, in Ewell's rear and flank. These turned out to be groundless, but led to two of Ewell's brigades being temporarily assigned to protect against the supposed threat.

25,000 Confederate and 18,000 Union soldiers had faced each other on July 1. Lee had won a first major success. He met that afternoon with the commanding general of his I Corps, Lieutenant General Longstreet, whose First Division would not arrive in the Gettysburg area until the morning of the next day after marching approximately 28 kilometers. Despite Longstreet's other suggestions, Lee decided to resume the battle on the wings the next day.

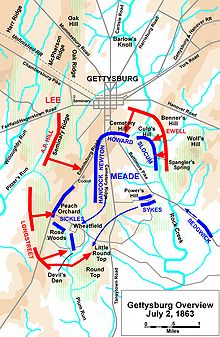

Second day (2 July)

During the night and morning of July 2, most of the infantry divisions of both armies reached the battlefield, only Longstreet's 3rd Division under Major General George Pickett would arrive late in the afternoon.

Major General Meade defended with the XII. Corps on Culps Hill, to the left of it with the remnants of I and XI Corps. Corps on Cemetery Hill, continuing south with the II Corps along Cemetery Ridge, and then following that with the III Corps under Major General Daniel E. Sickles to Little Round Top.

Lee's plan of operations for that day called for attacks on both wings of the Army of the Potomac. Longstreet was to attack the left wing astride the Emmitsburg Road to the northeast with three divisions, including Anderson's division from Hill's III Corps. Hill was also to threaten the center of the Union lines and see to it that the Army of the Potomac could not move troops from there to the wings. Ewell's job was to keep the right wing busy with two divisions and move to attack when a "favorable opportunity" arose. Lacking accurate reconnaissance due to the continued absence of Stuart's cavalry corps, Longstreet's left division under Major General Lafayette McLaws attacked Sickles' III Corps head-on rather than the Union left flank.

Sickles had taken up positions west of Cemetery Ridge on his own authority because the terrain there was somewhat elevated. He wanted to avoid being exposed to deadly artillery fire again, as at Chancellorsville, when he had to abandon the elevated terrain, the "high ground" 'Hazel Grove'. By this advance, however, Sickles overstretched the positions of the two divisions of the III Corps. As Meade told Sickles in the afternoon with the words.

"General Sickles, this is in some respects higher ground than that of the rear, but there is still higher in front of you, and if you keep on advancing you will find constantly higher ground all the way to the mountains!"

(German: "General Sickles, this is in some ways higher terrain than the one behind you, but there is still higher terrain ahead, and if you keep going you will keep finding higher terrain all the way to the mountains!")

However, it was too late to change positions again. Meade ordered the pioneer leader of the Army of the Potomac, Brigadier General Governor Kemble Warren, to reconnoiter suitable positions behind Sickles' Corps. Warren recognized the opportunities the two Round Tops would provide and recommended to the Commanding General of the V Corps, Major General George Sykes, that troops be sent there immediately to avert disaster for the entire Army of the Potomac. Sykes responded immediately and ordered the 1st Division of the Corps to the Tops.

Attacks on the left wing of the Potomac Army

Longstreet was to attack as early as possible; but the commencement of the attack was delayed because Longstreet had to wait for the arrival of a brigade, and during the approach an observation post on Little Round Top was detected. To remain undetected, the troops had to fall back. When Major General John B. Hood recognized Sickles' positions at about 4:00 p.m., Hood wanted to change the plan of operations and attack eastward of the Round Tops to the north, which Longstreet refused. Finally, on his own authority, Hood attacked both the Round Tops and Devils Den at about 16:30.

After capturing Devils Den, the Alabama Brigade under the command of Brigadier General Evander McIvor Laws, supported by two Texas regiments of Jerome Bonaparte Robertson's Brigade, attacked toward the Tops. Quickly reaching the heights of Big Round Top, the 15th Alabama Regiment immediately began its approach to Little Round Top when it came under murderous fire. The 20th Maine Regiment from Colonel Strong Vincent's brigade had arrived on the hill only ten minutes earlier. The commander of the 15th Alabama Regiment, Colonel William C. Oates, recognizing the importance of Little Round Top, repeatedly attempted to bypass the position of the 20th Maine Regiment under Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain on the right, but was unsuccessful. When the 20th Maine finally ran out of ammunition, Chamberlain ordered a bayonet charge that drove the 15th Alabama back to its initial positions. Gradually, more units of the 1st Division of the V Corps arrived and the situation at the Tops was stabilized. Hood's attack at Devils Den was lossy but successful, but could not be pushed further onto the Tops.

After Hood's brigades took Devils Den about 5:00 p.m., Law's division attacked the III Corps, which by then had been reinforced by brigades of the V Corps, at a wheat field and peach orchard. The Union units were pushed east out of the wheat field about 5:30 p.m., and at the same time the Confederates made a break at the plantation. The troops of the III and V Corps were in disbandment and, after heavy losses, fled toward Cemetery Ridge, north of the Tops, the area abandoned because of the 'High Ground' at the peach orchard at noon by Sickles.

A reinforcement from the II Corps, Brigadier General John C. Caldwell's division, ordered by Meade, reached the battle area about 6:00 p.m., and succeeded in stopping the Confederate corps attack for a short time. The Confederates attacked again through the wheat field about 7:30 p.m. and were again repulsed by a counterattack at the northern end of Little Round Top. Anderson's third division from A.P. Hill's corps, which had been readied for the attack, began the assault north of the peach orchard against the right flank of Sickle's corps about 6:00 PM. The two Union brigades deployed there had to move out of the way. This evasive movement was the catalyst for the collapse of the entire right wing of III Corps.

To allow time to prepare defenses along Cemetery Ridge, II Corps Commanding General Major General Winfield Scott Hancock ordered the 1st Minnesota Regiment to hold off the attacking Confederates by counterattack. Despite overwhelming Southern superiority, the regiment entered and lost 224 of 262 men in a matter of minutes, suffering the highest percentage loss ever suffered by a regiment of the United States Army. Wilcox's southern brigade was halted. The other two brigades deployed on the left wing of Anderson's division, however, quickly found the gap created by the collapse and pushed on to Cemetery Ridge. For a short time General Meade and his staff were the only Union defenders there. Whether the Southerners had reached the crest of Cemetery Ridge is a matter of historical dispute - but there is much to suggest that they had. Brigadier General Ambrose R. Wright, however, was unable to hold the crest of the ridge because he received no reinforcements. The brigades deployed to Wright's left advanced reluctantly or stopped. Even Anderson's express order to proceed ignored one of the brigade commanders. Eventually Wright was forced to move out onto the Emmitsburg Road again. The fight came to an end at nightfall across the board. During this attack Major General Pender was hit in the leg as he rode off the front of his division, which was forming to support the attack. Pender died as a result of the amputation. Brigadier General Lane first took charge of the division, after which it was placed under the command of Major General Trimble.

Attacks on the right wing of the Potomac Army

One division of the I. and two divisions of the XII. Corps of the Union had begun in the morning to fortify Culps Hill with positions. Ewell began the ordered diversion simultaneously with Longstreet's attack about 4:00 p.m., at first exclusively with artillery. Major General Meade, however, was not impressed by Ewell's actions. Meade ordered the commanding general of the XII Corps. Corps, Major General Henry W. Slocum, to make his corps available to support the wavering front on the left wing of the army. Slocum then withdrew all forces except Brig. Gen. George S. Greene's brigade.

Ewell did not order the attack on both hills until dusk began around 7:00 PM. Three brigades of Major General Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division attacked Culps Hill, Early's division Cemetery Hill. The difficulties for the attackers lay in the rapidly falling darkness, the rising terrain, and the built-up positions they encountered at Culps Hill.

The attacks of the two brigades attacking to the north from Johnson's division were repulsed. Brigadier General George Hume Steuart's brigade to the south managed to bypass the Union forces' positions to the south. Defending here, much like the 20th Maine Regiment at the other end of the Army of the Potomac, was the 137th New York Regiment under Colonel David Ireland at the extreme right of the army. The regiment succeeded, with heavy losses, in holding the right flank of the army with only minor losses of ground.

Since the troops were not used to fighting in the dark, there were incidents of casualties: The 1st North Carolina Regiment fired on the 1st Confederate Maryland Regiment. As the remnants of the XII. Corps returned to their positions, the soldiers found them occupied by Confederates. To put an end to this confusion and to avoid further casualties, the division commanders on both sides ended the engagement at about 11:00 p.m. in order to continue fighting at daybreak from the positions they had reached.

Early's brigades succeeded in advancing to the high ground at Cemetery Hill and captured several guns. Two newly approached Union regiments ended the infantry's melee with the gunners. In the process, the Confederate brigade commander, Brigadier General Harry T. Hays, realized that it was no longer possible to distinguish friend from foe. Moreover, when he was attacked by a brigade of the II Corps, he ordered a retreat to the foot of the hill. Rode's division was also to take part in the attack on Cemetery Hill. This, however, had not reached its initial positions until after dark. At the close of hostilities, Cemetery Hill was again in the hands of the Army of the Potomac.

The Southerners had missed a great opportunity at Culps Hill - the main line of communication for the Army of the Potomac ran up Baltimore Pike, only 600 yards from the positions of the 137th New York Regiment.

Stuart's cavalry had arrived in the Gettysburg area on the afternoon of July 2, but could not intervene in the action. Since this movement also caused the rest of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac to appear in the Gettysburg area, Johnson had to detach a brigade against this new threat.

Major General Meade, after a meeting with his staff and commanding generals, decided to wait for Lee's attacks the next day because of the losses of the Army of the Potomac. At the end of the meeting, Meade warned Brigadier General John Gibbon, by then commanding general of the Union's II Corps, that if Lee attacked the next day, he would do so before Gibbon's corps. Meade pledged support from the V and VI Corps. To the XII Corps. Corps Meade allowed an attack the next morning to retake the lost positions at the foot of Culp's Hill.

Lee, on the other hand, was ill-tempered, believing that his orders and plans had been poorly executed. Longstreet again proposed a strategic bypass of the Potomac Army's left flank, but Lee decided to attack both flanks again the next day, while Stuart would operate on Ewell's left and rear.

Casualties for Day 2 are difficult to estimate because both armies did not determine their respective strengths on a unit-by-unit basis until after the battle was over. It is estimated that the Northern Virginia Army had losses approaching 6,000 men, which meant losses of 30 to 40% for Longstreet's divisions involved in the attack. The Army of the Potomac lost about 9,000 men.

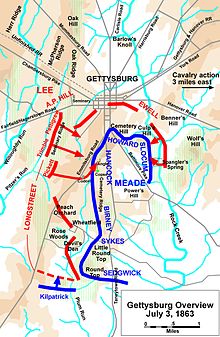

Third day (July 3)

Lee realised early on the morning of 3 July that his plan was not feasible - Longstreet was not yet sufficiently prepared for the attack and Ewell was already engaged in fierce fighting at Culps Hill. Lee's request to Ewell not to accept the engagement came too late.

The batteries of the XII. Corps had begun at dusk to shell Steuart's positions for 30 minutes. However, the Southerners forestalled the attack that was subsequently planned. In all, Johnson's soldiers attacked three times, but were repulsed each time. The fighting was over by 12:00 p.m. with an attack by two Union regiments, which was made head-on due to misinterpretation of the attack order. The commander of the 2nd Massachusetts Regiment, Colonel Charles R. Mudge, had the order repeated to him, and afterwards said:

"Well, it is murder, but it's the order." (German: "Well, it is murder, but order is order.")

During the bloody two-day fighting at Culps Hill, the Union lost about 1,000 men and the Confederates 2,800 men - one-fifth and one-third, respectively, of their respective team strengths.

Encouraged by the fact that the Confederate forces had almost succeeded in breaking through to the right of the center of the Army of the Potomac the day before, Lee decided to attack the enemy's center in a modification of the previous day's plan.

pickett's truck

170 Confederate guns began a two-hour bombardment of the artillery positions between Cemetery Hill and the Round Tops along Cemetery Ridge at 1:00 p.m.. Initially, 80 guns of the Army of the Potomac returned fire, but soon the commander of the artillery, Brigadier General Henry J. Hunt, ordered the fire to cease in order to have enough ammunition on hand for the expected infantry attack. Although Confederate fire was mostly too high because of poor visibility, casualties on both sides were substantial.

The artillery had nearly expended by 3:00 p.m. and the infantry attack began. Participating in the attack, under Longstreet's command, were Pickett's division from I Corps, and Isaac R. Trimble's (formerly Penders) and Pettigrew's (formerly Heth's) divisions from A.P. Hill's III Corps. The total strength of the troops engaged was close to 12,000 men. The attack began at Seminary Ridge on a width of more than a mile. The brigades advanced slowly eastward over a mile of open ground toward the Union positions on Cemetery Ridge. Immediately upon crossing Seminary Ridge, the Union batteries along Cemetery Ridge opened fire on the Confederate soldiers. Flanking fire from Cemetery Hill and north of Little Round Top in particular tore large gaps in the attacking lines. When the attackers were only 360 yards away, the artillery fired with cartridges, and the Union infantry joined in with musket fire. The Confederates shortened the line to half a mile and continued to attack. Pickett's division turned to the northeast. This offered the division's flank to the Union batteries, which could now fire parallel to the attackers' lines. Pettigrew's left flank suddenly faced a flank attack from the 8th Ohio Regiment, which caused the brigade engaged on the left to flee to the initial positions on Seminary Ridge.

The attacking Confederates pressed closer and closer in the center, forming a formation 15 to 30 men deep. Finally, at a low stone wall that here described a right angle, some 200 men led by Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead's, broke into the Union infantry positions and reached the first artillery positions. In the counterattack, the Confederates were again thrown out of the positions. This part of the stone wall - called "The Angle" because of the angle - later became known as the "High Water Mark of the Confederacy". The remaining Confederate units and formations slowly retreated to Seminary Ridge when it became clear that no reinforcements were being followed up. The entire attack, later called Pickett's Charge, lasted little more than an hour.

When Major General Pickett reported back to Lee, he ordered his division to prepare for a counterattack by the Army of the Potomac. Pickett responded:

"General Lee, I have no division now." (German: "General Lee, I have no division now.")

Confederate casualties were enormous - nearly 5,600 men, including all three brigade and all 13 regimental commanders from Pickett's division. The Union counterattack, however, did not take place. Although Northern casualties were much lower at about 1,500 men, the fighting strength of the Army of the Potomac was also exhausted and Meade was satisfied to have held the positions.

cavalry charges

Major General Stuart was to monitor the left flank of the Army of Northern Virginia with Confederate cavalry and break the main line of communication in the rear of the Army of the Potomac. Three miles east of Gettysburg, Stuart with four brigades, approximately 3,430 cavalry with 13 cannon, met Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg's division, reinforced by Brigadier General George A. Custer's brigade, approximately 3,250 cavalry, at about 1:00 p.m. Stuart immediately attacked with the 1st Virginia Regiment, but was counterattacked by the 7th Michigan Regiment under Custer's personal leadership - "Come on, you Wolverines! " - repulsed in the engagement with pistol and saber. Reinforcements enabled Stuart to put Custer's horsemen to flight. Stuart ordered a renewed attack with the mass of Brigadier General Wade Hampton's brigade. With sabers drawn, Hampton's horsemen charged the 7th Michigan Regiment. Gregg then ordered Hampton's flanks to attack. Pressed on three sides, the Confederate horsemen swerved to their initial positions. The entire engagement lasted about 40 minutes. Although a tactical draw, the engagement marked a strategic defeat for Lee because Stuart failed to get into the rear of the Army of the Potomac.

The Union cavalry division under Brigadier General Hugh J. Kilpatrick attacked Hood's division's positions from the south on both sides of the Emmitsburg Road at about 3:00 PM. In several waves, Kilpatrick had the cavalry regiments attack against infantry in positions first mounted, later dismounted. The Confederates repulsed all attacks, and a lieutenant of an Alabama regiment fired his soldiers, saying "Cavalry, boys, cavalry! This isn't a fight, it's a joke, give it to them!".

These ill-conceived and poorly executed cavalry charges marked the nadir in Union cavalry history and the last significant hostilities of the Battle of Gettysburg.

After the battle

The Northern Virginia Army had set up for defense on July 4 in anticipation that Meade would attack. The latter, however, decided against risking an attack, which later brought him severe criticism.

The Northern Virginia Army left its positions in the pouring rain that evening and marched along the Fairfield Road to South Mountain and thence to Virginia by way of the towns of Hagerstown and Williamsport, both in Maryland. During the retreat, Lee's special attention was given to the wounded and to the supply columns, the former because of his responsibility as a leader, the latter because these were the only means of enabling the army to continue fighting. Lee succeeded in getting the wounded, some of them transported under pitiful conditions - not even straw on the wagons and too few medics to care for them - the approximately 5,000 prisoners, the captured weapons and ammunition, and the supply vehicles to Virginia with only minor losses.

Meade followed Lee only half-heartedly. Even when the flooding Potomac forced Lee to remain on the north bank, it took too long for the Army of the Potomac to approach. The engagement with the rear guard on July 14 at Falling Waters in present-day West Virginia ended the Gettysburg campaign.

Union Soldiers Killed at Gettysburg

Defensive positions at Culps Hill, July 2, afternoon.

Fighting on the third day. red: Confederate troops blue: Union troops

West slope of Little Round Top, photograph by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, 1863.

High Water Mark today

Fighting on the second day. red: Confederate troops blue: Union troops

Fighting on the first day. red: Confederate troops blue: Union troops

Evasion of the Northern Virginia Army into Virginia from July 4-14. red: Confederate troops blue: Union troops

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Battle of Gettysburg?

A: The Battle of Gettysburg was a battle fought July 1–3, 1863 in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. It was the battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War.

Q: When did it take place?

A: The Battle of Gettysburg took place from July 1–3, 1863.

Q: Who were involved in this battle?

A: Union Major General George G. Meade's Army of the Potomac and Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia were involved in this battle.

Q: Why is Gettysburg often called the war's turning point?

A: Union Major General George G. Meade's Army of the Potomac stopped attacks by Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia during this battle, which ended Lee's second invasion of the North and is why it is often called the war's turning point.

Q: How many casualties resulted from this three-day battle?

A: Between 46,000 and 51,000 soldiers from both armies were casualties in this three-day battle.

Q: What happened on November that same year after this battle?

A: A cemetery for those who died at Gettysburg National Cemetery opened on November that same year after this battle and President Abraham Lincoln gave a speech called "The Gettysburg Address" at its opening ceremony to honor dead soldiers on both sides.

Search within the encyclopedia