Battle of France

Western Campaign

Part of: World War II

Western Campaign

Battle of the Netherlands

Maastricht - Mill - The Hague - Rotterdam - Zeeland - Grebbeberg - Afsluitdijk - Bombardment of Rotterdam

Invasion of LuxembourgCobbler line

Battle of BelgiumFort

Eben-Emael - K-W Line - Dyle Plan - Hannut - Gembloux - Lys

Battle of FranceArdennes

- Sedan - Maginot Line - Weygand Line - Arras - Boulogne - Calais - Dunkirk (Dynamo - Wormhout) - Abbeville - Lille - Paula - Fall Red - Aisne - Alps - Cycle - Saumur - Lagarde - Aerial - Fall Brown

The Western Campaign of the German Wehrmacht in World War II, also called the French Campaign with reference to the main objective, is the successful offensive from 10 May to 25 June 1940 against the four neighbouring countries to the west. Part of the offensive is known as the invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg.

The campaign, often referred to as the "Blitzkrieg", led to the defeat and occupation of the hitherto neutral states of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg (Fall Yellow) and France (Fall Red) within a few weeks. The final point was the Compiègne Armistice with France of 22 June, which came into force three days later. Unexpectedly, the operational success of the Panzer and Luftwaffe forces led to a war of movement that marked a turning point in the history of the war by a rapid course. The war against Great Britain could now be continued directly from the coast of the English Channel with the Battle of Britain in the air and in the naval war (Battle of the Atlantic).

Adolf Hitler at the headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Field Marshal von Brauchitsch (1940). From left to right. at the map table: Wilhelm Keitel, Walther von Brauchitsch, Hitler, Franz Halder

The initial situation at the end of 1939

Course and outcome of the battles in the spring and summer of 1940

Previous story

→ Main article: Prehistory of the Second World War in Europe

France in Hitler's strategic calculations

Adolf Hitler's long-term war goal since the 1920s was the conquest of "Lebensraum in the East. In his programmatic writing Mein Kampf, he had demanded the elimination of France as a condition for backing up the campaign against the Soviet Union. He also proclaimed this objective on 28 February 1934 in a speech at the Reich Chancellery to Reich military officers, declaring that in order to gain new living space he would lead "short decisive blows first to the west, then to the east." Hitler, however, remained flexible on the question of where to open the war; for example, in a speech to senior commanders on November 23, 1939, he confessed: "I have long doubted whether I should strike first in the East and then in the West." Finally, he decided to invade Poland.

Despite Hitler's targeted rearmament of the Wehrmacht from 1935 onwards, the principles of appeasement initially prevailed in the policies of France and the United Kingdom. Their representatives were prepared to tolerate revisions of the Treaty of Versailles for the sake of a tension-free coexistence of the large Central European states. The Anglo-German naval treaty, the toleration of the occupation of the Rhineland and the Anschluss of Austria, and the Munich Agreement, among others, should be seen in this light. The "crushing of the rest of Czechoslovakia" in violation of the treaty ended the appeasement policy. France and Britain now tried to build an alliance system to prevent further expansion of the German Reich: On March 31, 1939, the British-French Declaration of Guarantee was issued for Poland, followed by a similar declaration for Romania and Greece on April 13, 1939, and treaties of mutual assistance were negotiated with Turkey and the Soviet Union. The British government was the driving force behind this. With the conclusion of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact in August 1939, it became clear that these attempts at containment were unsuccessful.

Hitler had perceived the concessions of the Western powers as weakness on the part of states that - if not attacked themselves - would continue to shy away from a military confrontation with Germany in the future. This assessment, which in the end was shared only by Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, led Hitler to be convinced until the British ultimatum of 3 September 1939 that there would be no military confrontation with the Western powers over Poland. With Poland defeated, Hitler could turn his attention to eliminating France.

Tactical basics

France's post-war operational thinking was shaped by Marshal Philippe Pétain, the Inspector General of the French Army. In view of the horrendous losses France had suffered in its offensive operations in World War I and based on personal defensive successes ("Hero of Verdun"), he gave priority to defense and pushed for the expansion of a strong defensive wall, the Maginot Line. On the role of the tank weapon, his 1921 policy statements contain only the phrase: "Tanks support infantry action by defeating field fortifications and stubborn infantry resistance." The young armored officer Charles de Gaulle, on the other hand, proposed in his book Vers l'Armée de Métier that highly mobile, large armored units of professional soldiers seeking decision in attack be recruited as the core of land forces. With these ideas, however, he was able to assert himself only after Hitler's victory in Poland; until the beginning of the Western campaign, no significant implementation of the new strategy took place.

Under the impression of Hitler's occupation of the Rhineland and the inactivity of France, Belgium declared its neutrality on 14 October 1936. The mutual assistance pact with the Western powers was replaced by the crude secret agreement to offer joint resistance in the event of a German invasion in the "Dyle-Breda position". This line ran along the Belgian Meuse to Namur, then across the so-called "Gembloux Gap" to Wavre and from there along the Dyle via Antwerp and Breda to Moerdijk with a connection to the so-called Fortress Holland.

In the German Reich, tactics were determined by Colonel General Hans von Seeckt, who led the Reichswehr from 1920. He was convinced that the wars of the future would be won by well-trained, highly mobile armies supported by airmen. Since Germany had been denied such an army at Versailles (banning armoured and airborne vehicles, limiting it to 100,000 professional soldiers), he wanted at least to create the conditions for it. To ensure rapid expansion through troop increase after the restrictions were lifted, the mass of Reichswehr soldiers received training as leaders or specialists far beyond their current function. With regard to the development of modern weapon systems, cooperation with foreign countries was sought. Of particular importance was the German-Soviet cooperation that ran from 1922 to 1933 (tanks, combat aircraft, poison gas). Restrictions fell on March 17, 1935; the buildup of German offensive forces began. Their tactics: tank forces, together with infantry and with air support, forced a breakthrough and then advanced rapidly into the depths of the battlefield. The (motorized) infantry follows, eliminating pockets of resistance and securing the flanks of the advance with the help of anti-tank guns.

British troops passing a drawbridge on the Maginot Line at Fort de Sainghain, near the Belgian border.

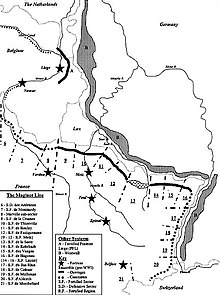

Course of the Maginot Line

Initial Situation

"Seat War"

→ Main article: Seat War

Two days after the German attack on Poland on 1 September 1939, France and the United Kingdom declared war on the German Reich; however, no serious offensive to relieve the Poles, who were under heavy pressure, took place either on the ground or in the air. France confined itself to an advance to within a few miles of the Westwall ("Saar Offensive"), and British Expeditionary Force (BEF) troops began to move into northern France. Attacks on targets in Germany planned by the Royal Air Force (RAF) were prohibited by the French, with reference to possible counterattacks. After the military defeat of Poland, the French commander-in-chief Maurice Gamelin took his troops back to the Maginot Line by mid-October 1939.

The following months were known as the period of the Sitzkrieg (French: la drôle de guerre; English: Phoney War), as activity on both sides was limited to reconnaissance. In France, which was deeply divided politically, opposition to the war continued to grow. The political about-face of the Soviet Union played a major part in this. Josef Stalin on 8 September 1939 in front of Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrei Zhdanov and Georgy Dimitrov:

"The war is being waged between two groups of capitalist states - (poor and rich in terms of colonies, raw materials, etc.) for the redivision of the world, for world domination! We have nothing against their hitting each other hard and weakening each other. It would not be bad if Germany were to shake up the position of the richest capitalist countries (especially England). Hitler himself, without understanding or wanting to, is shattering and undermining the capitalist system. [...] The Communists of the capitalist countries must stand resolutely against their governments, against the war."

The French Communist Party (PCF) then received instructions through the Comintern to break the Popular Front alliance with the Socialists and sabotage the country's war effort. Alleged acts of sabotage in the French armaments industry served as a pretext for banning the PCF throughout France by September 26, 1939. The actual amount of sabotage of the French defense effort is believed to be extremely small. A Communist organization within the army did not exist, nor did organized sabotage operations. In fact, only one case is known to have occurred at Farman, an aircraft manufacturer, in which Communists carried out sabotage on their own initiative in early 1940. The government blamed Communist propaganda for the deterioration of morale and lack of enthusiasm for war, although it neither spread defeatism nor encouraged its members to desert or fraternize with the enemy.

Planning

Allied

The Allied strategy was determined by the French. These planned not to undertake any cross-border operations before the early summer of 1941. German attacks were to be repelled at the Maginot Line, which extended from the Swiss border to Sedan and in which Army Groups 2 (Prételat) and 3 (Besson) were deployed. An attack across Belgium was to be brought to a halt in the Dyle-Breda position. In this position, Army Group 1 (Billotte) was to be deployed together with the British Expeditionary Corps (9 divisions) and parts of the Belgian and Dutch armies.

Command structure: Commander-in-Chief Gamelin had handed over responsibility for the northeastern front (Army Groups 1-3) to his deputy, General Alphonse Georges, on 6 January 1940; coordination of the deployment of French Army Group 1, the British Expeditionary Corps and the Belgian and Dutch forces was transferred to General Billotte after the invasion of Belgium.

Belgium and the Netherlands

The Belgians had three fortified places, Liège, Antwerp and Namur; but the bulk of the army (20 divisions) was to be deployed in the border positions with Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, as well as in depth along the Albert Canal. The development of a third defensive line, the K.-W. position (Koningshooikt-Wavre-Stellung), designated by the Allies as the Dyle-Breda position, was not begun until August 1939.

The Netherlands hoped to maintain its status of neutrality, as in the First World War, and was therefore not prepared to make defensive agreements. One's own defence was planned along the Maas and IJssel; the Peel-Raam and Grebbe positions were envisaged as a second line. Fortress Holland" (area of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague) was to be defended along the "New Water Line" at the height of Utrecht. The state of development of these lines was low compared to those of the Belgians; also the level of training of the Dutch troops was worse than that of the Belgians.

Luxembourg

The neutral and unarmed Luxembourg had only a small volunteer corps of 461 men, so that armed resistance was inconceivable. The Schuster Line was built along the border with Germany. It was named after the construction conductor Schuster and was supposed to hinder an advance of German troops with steel gates and concrete blocks.

German

When Hitler announced his decision to attack the Western Powers immediately after the end of the Polish campaign on 27 September 1939, this caused "the greatest horror" among the general staff because of the strength ratio. After Hitler had rejected all counter-arguments, planning began. In the first three operation drafts, the focus was on the north (Army Group B). As a counter-proposal, the then Chief of Staff of Army Group A, Lieutenant General Erich von Manstein, presented his Sichelschnitt plan, developed together with Panzer General Heinz Guderian, which envisaged a surprise thrust of Army Group A through the Ardennes as its core. This plan did not meet with the approval of Chief of Staff General Franz Halder because of the key tank terrain in the Ardennes. He transferred the inconvenient Manstein to a rather insignificant position as Commanding General of a newly formed corps in Schwerin.

Hitler's decision to attack in the West became definite when there was no positive response to his "peace speech" of 6 October. Already on 9 October, when the effect of his speech had not yet become apparent, Hitler had completed a memorandum on the subject of the necessity of immediate attack and issued Directive No. 6 for the conduct of the war (Geheime Kommandosache, OKW No. 172/39). Shortly thereafter he named the period between 15 and 20 November as the date of attack. On 23 November 1939, he informed the General Staff in a speech of his "unalterable decision" to attack England and France "at the most favourable and rapid time".

Old and new plans

→ Main article: Mechelen incident

On January 10, 1940, however, the entire previous plan was rendered moot by a bizarre incident when Luftwaffe officer Major Helmut Reinberger was delayed in Münster with explosive files while traveling to a staff meeting scheduled in Cologne. He decided to accept the offer to fly in an Luftwaffe courier plane to save himself the long trip by overnight express train, even though he was violating a clear order from Hermann Göring not to deliver classified information by air. His briefcase contained the top-secret plan for an important part of the German invasion of France and the Netherlands.

Soon after the Messerschmitt Bf 108 took off from Münster-Loddenheide airfield, thin veils of fog condensed into a closed cloud cover, and strong easterly winds caused a wind shift of about 30 degrees. The Rhine, an important orientation line, was flown over unnoticed in poor visibility. The pilot, Major Erich Hoenmanns, finally sighted a river and realized that it could not be the Rhine. In the damp, freezing air, the wings and carburetor of their plane iced up; then the engine quit. Hönmanns found a small field just in time for an emergency landing. Unhurt, the two Wehrmacht officers realized that they had flown over the Meuse River and crash-landed 80 kilometers west of Cologne near Vucht in Belgium (today: Maasmechelen).

Reinberger wanted to burn the papers immediately. But since neither of them had matches with them, they borrowed a lighter from a farmer who had rushed over. Just as Reinberger had succeeded in setting fire to the papers despite the strong wind, Belgian gendarmes arrived and extinguished the flames.

That same evening, the legible documents were available to the Belgian General Staff, which immediately ordered the mobilization of the Belgian forces. The Belgians also transmitted to the French and British armies in northern France a summary of the contents of the documents found with Reinberger. This operational plan indicated that the German army was to advance into France in an encircling movement through Belgium - similar to the Schlieffen Plan.

Hitler strongly reproached Göring and ordered the courier to be shot on his return, which never happened as Reinberger and Hönmanns spent the entire war in a Canadian prisoner of war camp. Circumstances, however, led to the very important decision to devise a completely new German plan of attack.

This is what Erich von Manstein did; he discarded the old plan of a main thrust through Belgium, which the Allies could now predict at the latest, and worked out a plan later called the Sichelschnittplan. As he explained to Hitler on 17 February 1940, the German focus of attack was instead to be in the Ardennes, a wooded mountainous area in the border region between Belgium, France, and Luxembourg that was considered impenetrable: the unexpected direction of attack would not only give the Germans the advantage of surprise, but also put them in front of the section of the French border with the weakest defense. The German tanks were to penetrate the French positions at Sedan (which they later actually succeeded in doing remarkably quickly), drive a wedge all the way to the English Channel, and split the Anglo-French armies. The air-superior German Luftwaffe was to protect the columns of tanks and vehicles as they marched along the narrow Ardennes roads, and then lay a carpet of bombs in front of the tanks as they advanced into France. The plan was highly risky, as the flanks of the German troops would initially be largely unprotected, so that they themselves ran the risk of being encircled.

Occupation of Denmark and Norway

→ Main article: Enterprise Weser Exercise

Denmark and Norway had remained neutral in the First World War. Following the suggestions of the German Naval High Command (OKM) regarding an occupation of these two countries, Hitler gave the "green light" for planning on December 14. The main objective was to secure supplies of Swedish iron ore, which were vital to the war effort. After the invasion of Finland by troops of the Soviet Union (30 November 1939), the British and French also developed plans to become involved in this area. In addition to opening a land route to support the Finns, they also wanted to cut off Swedish ore shipments to Germany via Narvik. After the Finnish surrender and the Finnish-Soviet peace treaty of 12 March 1940, it was decided to send troops to Norway in early April, even for the sake of ore. Largely at the same time, the Wehrmacht launched Unternehmen Weserübung on 9 April 1940. The Royal Navy inflicted considerable losses on the invading forces, who were advancing en masse by sea. However, it could not prevent any of the landings and had to withdraw from the coastal area after air attacks. The British ground forces landing in Narvik and central Norway from 15 April remained isolated and had to be evacuated after a few weeks.

In France as in Great Britain, the invasion of Norway triggered government crises. In France, Paul Reynaud became Prime Minister and Édouard Daladier took over the army portfolio. British Prime Minister Arthur Neville Chamberlain also faced severe reproach over the conduct of the Norway venture. Although he won the vote of confidence, albeit narrowly, he resigned. He was succeeded on 10 May 1940 by Winston Churchill, who formed an all-party government.

Messerschmitt Bf 108

Various drafts for the Western campaign

November 1939: Members of the British Expeditionary Force and the French Air Force in front of a hut marked "No. 10 Downing Street" (the address of the British Prime Minister).

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Battle of France?

A: The Battle of France, also known as the Fall of France, was a German invasion of France and the Low Countries that began on 10 May 1940 and ended with an armistice signed on 25 June.

Q: What were the two parts of the battle called?

A: The first part was called Fall Gelb in German (Case Yellow in English), while the second part was called Fall Rot in German (Case Red in English).

Q: When did Italy start its own invasion?

A: Italy started its own invasion of southeastern France on 10 June.

Q: When did Germany take Paris?

A: Germany took Paris on 14 June.

Q: When did France surrender?

A: The French Second Army Group surrendered on 22 June.

Q: What happened to France after it surrendered?

A: After surrendering, France was split into a German-occupied part in the north and west, a small Italian-occupied part in the southeast and a satellite state part in the south that was called Vichy France. Southern France was taken over by Germany until after Allied forces returned in 1944. The Low Countries were freed during 1944 and 1945.

Q: How did most British Expeditionary Force soldiers escape from Dunkirk?

A: Most British Expeditionary Force soldiers escaped from Dunkirk during Operation Dynamo.

Search within the encyclopedia