Battle of Antietam

Battle of Antietam

Part of: American Civil War

Confederates killed at Antietam, lined up for burialPhoto

by Alexander Gardner.

Maryland Campaign

South Mountain - Harpers Ferry - Antietam - Shepherdstown

The Battle of Antietam (ænˈti təm), also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg, especially in the Southern states, was the decisive battle of the Confederate Maryland Campaign during the American Civil War. It took place on September 17, 1862, along the Antietam River near the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland.

It is considered the most important battle in the Eastern Theater of War in 1862. General Robert E. Lee had led the Army of Northern Virginia into Northern territory for the first time in the Maryland Campaign after the failure of the Union Peninsula Campaign and the Confederate victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run. There it was again opposed by the Army of the Potomac under Major General George B. McClellan. By chance, detailed operational plans fell into McClellan's hands before the battle of Lee, showing the vulnerability of the enemy. However, he missed several opportunities to press the advantage.

Therefore, although McClellan's troops were ultimately able to force the Confederates into a temporary retreat with heavy casualties, the Battle of Antietam did not bring a decision to the eastern theater of the war, but is considered a missed opportunity for the Union to inflict a crushing blow on the Northern Virginia Army and bring an early end to the Civil War. It was the highest casualty one-day battle of the entire Civil War. Because of the approximately 3,600 casualties and total losses of about 23,000 men, September 17, 1862 is also known as the "bloodiest day in American history."

At the same time, its outcome signified a strategic victory for the Union, as it is considered by leading historians to be one of the most important turning points of the war politically. For even if the military success of the Union troops had ultimately been limited, the dearly bought victory nevertheless opened up the possibility for Lincoln to announce his Emancipation Proclamation to free the slaves in the southern states from a position of strength, undermined efforts by Great Britain and France to bring about a negotiated peace with a consensual division of the United States, and helped Lincoln's Republican Party to avert a threatened defeat in the congressional elections in the fall of 1862.

At Antietam, for the first time, the consequences of a Civil War battle were documented in detail photographically. Alexander Gardner's photographs of dead soldiers shocked many viewers and led to a more realistic assessment of the previously idealized events on the battlefields.

Previous story: The Civil War in 1862

Military situation at the beginning of the year

In the second calendar year of the American Civil War, much of the Union (Northern) effort in the important theater of war in the East continued to focus on capturing and occupying Richmond. The fall of their capital, located only 100 miles (160 kilometers) as the crow flies from Washington in Virginia, would, it was hoped in the North, deal a crushing blow to the Confederacy (Southern states), collapse the government of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and render null and void the secession of the South, which was considered a "rebellion." To achieve these war aims, however, the Union had to go on the offensive, while the Confederates could confine themselves to defending their own territory.

One obstacle on the way to Richmond was a series of smaller and larger rivers that ran parallel to the Virginia border between it and the Confederate capital. Initial attempts to capture Richmond, then, had failed in the early stages the previous year with Union defeats at the First Battle of Bull Run (July 21, 1861) and the engagement at Balls Bluff on the Potomac (October 21, 1861). Since then, General Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate army, standing between Manassas and Centreville, had been able to hold off the numerically vastly superior Union Army of the Potomac from making any advances into Virginia. The result was a stalemate that bothered the North more than the South.

Major General George B. McClellan, commander-in-chief of the Army of the Potomac, had demonstrated his organizational talents between the summer of 1861 and early 1862, turning a beaten army into a well-structured one with renewed self-confidence. The press had therefore elevated him to the status of "young Napoleon." In fact, he was a procrastinator and perfectionist who shied away from risk and - even confronted with clearly inferior units - constantly pressed for further reinforcements of his own troops and better preparations before their deployment. McClellan tended to overestimate the numerical strength of the enemy (often many times over) and to use the miscalculation to justify his lack of initiative. This made him vulnerable to attacks from political opponents, who sometimes even accused him of sympathizing with the Southern cause. Among his troops, the charismatic general was nevertheless very popular.

As brief commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army, McClellan achieved a series of successes in other theaters of war during the winter of 1861/2, although his personal contribution was small. In the West, the Union captured the Confederate forts of Fort Henry (February 6, 1862) and Fort Donelson (February 16) in Tennessee, thus controlling for the first time important tributaries to the Mississippi River, a possible route of incursion into the South. The fall of Nashville (February 25) further consolidated the Union position. Between February and April, an expeditionary force also succeeded in capturing much of the Confederate ports on the North Carolina coast.

Attempts by several Confederate armies to halt a further Union advance in Tennessee ended in defeat at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7), the Civil War's heaviest-loss battle to that point. Union armies subsequently captured Corinth, a railroad junction in northern Mississippi (April 30). The fall of Confederate positions and towns along the Mississippi River such as Island No. 10 (April 7), New Orleans (April 24), Baton Rouge (May 9), and Natchez (May 12) completed the series of Union military successes in the winter and spring of 1862.

This development made the disappointments of 1861 forgotten and renewed the hope from the beginning of the Civil War that the Southern rebellion could be ended within a few weeks. At the same time, the voices of the pessimists were multiplying in the Southern states. Confederate Vice President Stephens declared in private as early as February 1862, "The Confederacy is lost."

Peninsula Campaign and Second Battle of Bull Run

Urged by Union President Abraham Lincoln to go on the offensive, General McClellan devised a plan in early 1862 to bypass Johnston's supposedly superior force and Virginia's running waters. To do this, his army was to be transported by ships across the Chesapeake Bay to the eastern shore of the state and from there march on the Confederate capital. Lincoln consented to the scheme, although he would have preferred McClellan to attack Johnston's army standing near Washington at Bull Run instead of going directly against Richmond.

McClellan's campaign began on March 17 with the landing of initial units of the 120,000-man Army of the Potomac at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, about 100 kilometers from Richmond. The Union advance quickly came to a halt, however, with the month-long siege of Yorktown (beginning April 5). This left Johnston ample time to withdraw his force, now called the Army of Northern Virginia, to protect Richmond. Only after a Union victory at Williamsburg (May 5) could the Army of the Potomac advance further. Richmond now seemed seriously threatened. Johnston's attempt to stop McClellan with an attack five miles from the city failed due to the undecided outcome of the Battle of Seven Pines (May 31-June 1), in which Johnston was moreover seriously wounded.

The supreme command of the Army of Northern Virginia now passed to General Robert E. Lee. He had served as military advisor to President Davis since March 1862 and had helped conceive Major General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's Shenandoah campaign, which had brought the first significant Confederate successes in 1862. McClellan expected Lee to take a defensive posture, but he decided to attack the Union army. Almost all of the fighting in the ensuing Seven Days' Battle (June 25-July 1) resulted from attacks by the numerically outnumbered Confederates. Although Lee's complex attack plans mostly failed and his army suffered heavy casualties, McClellan was impressed by the enemy's variant offensive. He withdrew his troops to the James River, where they remained idle for the remainder of July.

McClellan demanded reinforcements from Washington to counterattack the supposed 200,000-man Northern Virginia Army - a threefold overestimate of its size. As he continued to ramp up his demands, an unnerved Henry Wager Halleck, new commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army, ordered a withdrawal from the peninsula in early August. McClellan was to unite his Army of the Potomac, which still had 90,000 men, as quickly as possible with the 40,000-strong Virginia Army under Major General John Pope, which had meanwhile advanced into northern Virginia. Lincoln had allowed the new major Union force to be formed and deployed on the Potomac only in June because he felt the city of Washington was inadequately protected due to McClellan's campaign. The reluctant McClellan was uncertain whether he or Pope would command the combined army. Therefore, he secretly hoped for a defeat of his rival against several divisions Lee had sent to fight the Virginia army under the command of Jackson. McClellan, meanwhile, was taking his time in shipping his own army back.

Jackson scored an initial success against part of Pope's forces at the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9. With the withdrawal of McClellan's army looming, Lee left 22,000 men to defend Richmond and rushed to Jackson's aid with the rest of the Northern Virginia Army. He was determined to provoke Pope to battle with his total of 55,000 men before the latter's Virginia Army could unite with the entire Army of the Potomac.

Sent out by Lee to disrupt Union supply lines, Jackson's divisions raided and destroyed a large Union camp at Manassas Junction on August 27. Pope now decided, with the expected reinforcement of four divisions of the Army of the Potomac and two divisions withdrawn from North Carolina, to face Jackson before he could reunite his forces with Lee's. Due in no small part to Pope's confused command of units from three armies that had never fought together, however, the Union forces suffered a humiliating defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28-30) and were forced to retreat across Maryland to Washington. McClellan had prevented other ready divisions of the Army of the Potomac from coming to Pope's aid, despite Halleck's orders to the contrary.

Course of the battles in northern Virginia in the summer of 1862

Robert E. Lee

Advance of the Army of the Potomac on the Virginia Peninsula

"Ingenious Inaction" Or Six Months on the PotomacCartoon on the Stalemate in the East. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper , February 1862

George B. McClellan

Domestic and foreign policy reactions

"Hard" warfare and slave liberation

The turnaround in the military situation between March and August 1862 was dramatic. While the Union had hoped to end the war quickly in the spring, both of the Union's major formations in the eastern theater of war had suffered staggering defeats in the summer. The failure of the Peninsula campaign was repeatedly compared to Napoleon's fiasco in Russia. The Union also suffered setbacks in the western theater of war in the summer of 1862, although these were not as momentous. Moreover, the Northern Virginia Army, strengthened under its new commander-in-chief, Lee, threatened to advance into the northern states for the first time, even attacking Washington, Baltimore, or Philadelphia. While in the Southern states, after months of largely depressing news from the battlefields, a new confidence prevailed, in the Union states the certainty of victory turned into astonished horror, sometimes even panic.

In the North, domestic political antagonisms intensified, partly because congressional elections were coming up in the fall. The "War Democrats", i.e. those members of the Democratic Party who approved of the war in principle but criticized the attitude of the ruling Republicans as too intransigent, found themselves in a quandary. They attacked Lincoln because McClellan, himself a Democrat, had not received the requested reinforcements. For their part, many Republicans and newspapers supporting them, such as the New York Times, cast doubt on McClellan's account of the balance of forces on the Peninsula, accusing the commander-in-chief of the Army of the Potomac of a lack of will to fight, of treating the civilian population in Virginia too gently, or even of treason in light of his conduct toward Pope. The criticism was shared by some leading officers of the Army of the Potomac.

Although President Lincoln was deeply angered by McClellan's inaction since the Seven Days' Battle, he resisted appeals from his cabinet to dismiss the general or even bring him before a war tribunal. Instead, in early September, he asked McClellan to continue leading the Army of the Potomac, united with the troops of the deposed Pope, and to protect the city of Washington from the feared siege by Lee. Fierce opposition from his ministers was met by Lincoln saying, "McClellan has the army on his side [...and] we must use the tools we have."

Doubts about McClellan's loyalty were exaggerated, but he did indeed disapprove of the hard-line war course of radical Republicans, whom he suspected of having an outsized influence on the despised Lincoln. Like almost all Democrats, McClellan opposed above all turning the war for the unity of the country into a fight against slavery in the Southern states. With his help, supporters of the general spread rumors that effective military leadership, and thus early victory with few casualties and no Confederate humiliation, would be sabotaged by men like Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton until the more radical war aims could gain public acceptance.

Personally, Lincoln viewed slavery as a moral evil. However, he had opposed the demands of prominent abolitionists and individual party members during his first year in office to make the freeing of slaves in the South a war goal. The president feared above all that this would lead to the secession of the four slave states that had remained loyal to the Union, the border states of Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri. On the other hand, the exploitation of slave labor played an important role in the war economy of the South. Early on, therefore, the practice of treating runaway or captured slaves from the Southern states as spoils of war that would not have to be returned to their "owners" had become established in the Union army. The Republican-dominated Congress had signed this procedure into law on March 13, 1862.

During the summer of 1862, Lincoln became convinced that the old Union of slave and non-slave states could not be restored due to the strengthening of Confederate resistance. The final abolition of slavery was to be the basis of a new Union, and the Southern states were to be forced to accept it by any means available, including harsher treatment of civilians. In changing course in this way, the president was determined to disregard countervailing advice from military leaders like McClellan and from representatives of the slave states of the Union (whom he sought to persuade to voluntarily abandon slavery).

On July 22, Lincoln opened to his astonished cabinet that he had come around to issuing a proclamation emancipating slaves in the Confederate states (though not in Union states), based on his rights as commander in chief in time of war. Nearly all the ministers supported the change of course, but Secretary of State William H. Seward warned of the possible diplomatic consequences. There was speculation in Europe that the Union, in view of recent reverses, must pin all its hopes on a rebellion by slaves in the Southern States. Therefore, he said, a declaration of emancipation before a major Union military victory might be seen as "the last measure of a spent government, a cry for help," "our last cry in retreat."

In light of Seward's warning, Lincoln decided to shelve the Emancipation Proclamation for the time being. Only the victorious outcome of the Battle of Antietam two months later gave the opportunity to publish it.

Threat of diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy

The recent Union defeats threatened to have serious foreign policy consequences for the United States in the summer and fall of 1862.

From the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy hoped for recognition of its independence by the great European powers of Great Britain and France and even for their subsequent military intervention in favor of the South. The textile industries of both countries, which had officially declared their neutrality, depended on cotton imports from the Southern states, and the Confederates early on organized a unilateral embargo on exports to put economic pressure on the Europeans. In Britain, many leaders felt a connection to the "aristocratic" lifestyle of Southern plantation owners, but viewed the slave economy as an eyesore that stood in the way of recognition. On the other hand, it was pointed out that even the Union had not officially made the abolition of slavery a wartime objective, so it was not a mandatory precondition for establishing diplomatic relations with the Confederacy.

Europe was skeptical about the Union's ability to militarily subdue the vast territory of the southern states, but shied away from early advocacy of either side. Emperor Napoleon III, while inclined to recognize it from the start, wanted to act only in concert with the British government in this regard. In London, however, Prime Minister Palmerston let it be known as early as 1861 that the Confederacy could only expect recognition if it proved its viability through victories on the battlefields. Charles Francis Adams, Lincoln's ambassador in London, repeatedly warned his government of the dramatic consequences that could result from further Union defeats.

The worsening cotton crisis and the successes of Jackson and Lee in the Shenandoah Valley and off Richmond actually renewed appeals in Europe for recognition of the Southern states in the summer of 1862. President Lincoln, who considered the western theater of the war more important than the eastern, expressed his displeasure at what he saw as a distorted perception of the war situation abroad.

In a debate on 17 July, the British Parliament was only dissuaded from calling for a peace settlement on the basis of a partition of the USA by an intervention of the Prime Minister. Meanwhile, Palmerston himself changed his position shortly thereafter. On August 6 he wrote to Queen Victoria that Britain should soon propose an armistice. On 24 September (before news of the Battle of Antietam had reached London) he agreed with Foreign Secretary John Russell to launch a negotiated peace initiative between North and South in October, agreed with France. If Washington rejected this, London would unilaterally recognize the Confederacy.

John Bull's Neutrality - The guardian of civilization in full action. London falls in with American liberty struggling with rebellion. Caricature from Harper's Weekly, September 1862

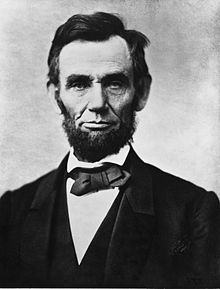

Abraham Lincoln

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Battle of Antietam?

A: The Battle of Antietam was an important battle in the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland.

Q: Why is it also called the Battle of Sharpsburg?

A: It is also called the Battle of Sharpsburg by South historians.

Q: Why was the Battle of Antietam significant?

A: It was the first major battle in the Civil War that took place in the border states.

Q: What was the purpose of both sides in the Battle of Antietam?

A: Both sides hoped a big victory for their side would make a short war.

Q: How many soldiers were killed, wounded or missing at Antietam?

A: About 22,720 soldiers were killed, wounded or were missing at Antietam.

Q: Was Antietam the bloodiest battle in the Civil War?

A: Yes, it was considered the bloodiest battle in the Civil War.

Q: Has there been another single-day battle in the history of the United States with so many American casualties?

A: No, there has never been another single-day battle in the history of the United States with so many American casualties. However, there have been other battles that lasted for more than one day where more Americans fell. For example, the later Battle of Gettysburg lasted three days and had an estimated 51,000 American casualties.

Search within the encyclopedia