Stonehenge

![]()

This article discusses the structure. For the progressive metal band of the same name, see Stonehenge (band); for the asteroid of the same name, see (9325) Stonehenge.

51.1788888889-1.82638888889Coordinates: 51° 10′ 44″ N, 1° 49′ 35″ W

Stonehenge [stəʊ̯n'hɛndʒ] is a structure near Amesbury, England, built over 4000 years ago in the Neolithic period and used at least until the Bronze Age.

It consists of a ring-shaped earthen wall, inside of which there are various formations of worked stones grouped around the center. Because of their gigantic size they are called megaliths. The most conspicuous among them are the large circle of formerly 30 standing blocks, which originally carried a closed ring of 30 capstones on their upper side, and the large horseshoe of originally ten such columns, which were connected with each other by a capstone placed on top to form five pairs, the so-called triliths. Within each of these horseshoes and circles stood two figures similar in form: both made of much smaller, but formerly twice as many stones.

These four formations are complemented by the "Altar" near the center of the site, the so-called "Sacrificial Stone" inside - and the Heelstone a good distance outside the northeastern exit. In addition, three concentric circles of holes were made in the ring wall, and in the largest of them four menhirs were arranged to form a rectangle, the short sides of which are parallel to the long axis of the monument. Other structures from the megalithic period - mainly tumuli and two structures called racetracks - can be found in the surrounding area. In addition, there are the remains of the so-called processional way, which extends from the aforementioned exit to the right to the Avon bank. The radius leading downward into the entrance of the monument, in its extension, then points to the south coast of England; interestingly, precisely to the common mouth of the rivers Avon and Stour into the English Channel (see Christchurch Harbour). Accordingly, there could have been processions that on certain days began in the morning towards the northeast, descended to the coast following the apparent path of the sun, and ended in the evening returning to the monument.

Recent research suggests that Stonehenge, and with it the culture that built it, should not be considered in isolation from similar structures. At the point where the Processional Way meets the Avon River lies the smaller Bluehenge. Possibly there is also a connection with the nearby Durrington Walls site or, in general, a motive common to the various peoples that led to the development of the megalithic cultures.

There are various hypotheses about the occasion and ultimate purpose of this highly elaborate structure, some of which complement each other and some of which contradict each other. They range from the self-portrait of a primeval political alliance of two formerly hostile tribal organizations (size hierarchy of the menhirs) to a religious burial or cult site to an astronomical observatory including a calendar for sowing and harvesting times.

All these hypotheses, even the more purely speculative ones, agree on one point: The architects of the monument managed to align the horseshoes and the stones perpendicularly in front of their openings exactly with the sunrise of that time on the day of the summer solstice.

The path from the simplest to the most complex, ultimately remaining embodiment of this plant can be divided into at least three sections:

- The beginning of the first phase, during which a circular earthen wall with a ditch surrounding it was built, is dated to about 3100-2900 cal BC and lasted until about 2900-2600 cal BC (or even until 2100 BC).

- The following second phase with the Aubrey holes as remains of the largest of the three circles of holes mentioned at the beginning, in addition with further holes outside the ring wall from the first half of the third millennium B.C. (cf. chap. Stonehenge 1), lasted until ca. 2500/2400 cal B.C. (or until 2000 B.C.). The Aubrey holes are usually interpreted to have served as burial chambers and/or to have held wooden posts.

- The stone constructions were built from about 2400 to 1500 cal BC, whereby earlier designs were radically modified several times.

According to first vague indications, the beginnings of the site as an actual megalithic monument go back much further than assumed so far; thus, there seems to have been a first version of stone structures already around 3000 BC. The further explanations in this article, however, refer to the dating that has been assumed as certain so far.

Recent research suggests that the place where the remains of the monument can be seen today already had a special ritual significance for people 11,000 years ago.

Since 1918, the monument has been owned by the English state; it is managed and developed for tourism by English Heritage, and its surroundings by the National Trust. UNESCO declared Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites a World Heritage Site in 1986.

Stonehenge in July 2008

Overview

The name Stonehenge is already documented in Old English as Stanenges or Stanheng. While the first element of the name is the Old English word stān "stone", there is uncertainty about the second element. It could be hencg "hinge, hinge" or a nounic derivation from the verb hen(c)en "to hang," which would then mean "gallows." In fact, medieval gallows possessed two feet and thus resembled the triliths in the center of the monument. The also attempted interpretation as "(in the air) hanging stones", however, lacks semantic consistency.

The second component of the name, henge, is used today as a technical archaeological term for that class of Neolithic structures consisting of a ring-shaped raised enclosure with a ditch running along the inside. Stonehenge itself, according to current terminology, is a so-called atypical henge, since the ditch lies outside the ring wall.

The complex was continuously modified or built in several phases. These activities extend over a period of about 2000 years. However, the site was demonstrably used even before the first stone construction. Three large presumed postholes located outside the ring wall near the present parking area date to the Middle Stone Age, around 8000 B.C. In the vicinity of the cult site, the remains of cremated burials were found in soil samples dating to between 3030 and 2340 B.C.. Accordingly, site was in use as a burial ground even before the stones were erected. The most recent cultic activities (Druids, origin of the Avalon saga?) date back to about the 7th century AD, the artifact to be mentioned here is the grave of a beheaded Anglo-Saxon.

Dating the various phases of the monument's design and understanding their meaning is difficult, since earlier excavation methods did not meet today's standards and there are still hardly any theories that would make it possible to gain a comprehensively informed insight into the thoughts and actions of the people of that time.

Thus, among other things, it remains uncertain what was the function of the holes found in the ground. Some scholars consider that they originally had the task of receiving supporting pillars for the purpose of a no less speculative roofing of the place. Others, on the other hand, hold that such hypothetical trunks were merely phallic symbols or totem poles that were later replaced by towering rocks in the wake of technological advances and cultural-demographic changes (population growth, increase in labor force).

One intuitively understands that the purpose of such constructions is to impress the observer already from a distance, i.e. also to make enemies think twice before they dare to attack. The successive expansion of the constructions could then be interpreted as a symbolic 'arms race' between neighboring tribes. Whether such a dynamic is compatible with the long periods of further development of the monument, however, remains the question. It has also been suggested that the ever-changing structures of Stonehenge reflect memories of the course of military conflicts, for example the displacement of a numerically stronger 'native population'. Such a process could be reflected in the bluestones which were temporarily completely removed (?) from the ring wall. The fact that this inferior culture was subsequently integrated into the territory of the victors - possibly they expressed their superiority especially by the enormous Sarsen horseshoe - would then correspond to the often observed result of a preceding territorial dispute (see also below, in the chapter Urpolitik in the context of the Bluestones and the commentary in section Phase 3 III).

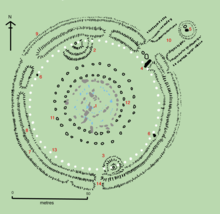

The fact that so far only little material has been discovered from which 14C data could be obtained further complicates the tracing of the temporal development of these cultures, and thus also of the changes to the shape of the monument that were gradually made and only discovered archaeologically in the first place. The sequence of these interventions, which is mostly accepted today, is explained in the further text with reference to the illustrated plan sketch. The megaliths still found today are highlighted by coloring their outlines (blue, brown and black); the capstones of the two Sarsen formations were left out for reasons of clarity, and there is speculation about the disappeared remainder of the thus heavily damaged complex. Partly, the monument was probably used as a quarry for the construction of churches, fortresses and palaces of the powerful during the feudal phase of England, but there are also clear traces of deliberate destruction. Modern archaeology usually interprets carefully dismembered columns, smashed effigies, etc. in the sense of the destruction of a culture by the subsequent victors; in parallel, there seems to have been a change in burial customs from about 1400 cal BC (from megalithic communal graves to graves for individual rulers), which can also be interpreted in this sense.

Plan of the present Stonehenge

The plant

The Heelstone and the Sacrificial Stone, and with them the openings of the two central horseshoes, were aligned with the position of the sunrise at midsummer; also, among others, the four stones of the rectangular structure on the ring wall seem to have had to do with various periodicities of celestial mechanics. For these reasons, Stonehenge is often thought to have been a prehistoric observatory, although the exact nature of its use and its significance, such as for sowing and harvesting at the best possible times (see below), are still debated.

Description of the stones (from the inside out)

- The altar stone: a block of five meters of green sandstone closest to the center of the complex.

- Immediately adjacent to it is the small horseshoe: It housed 19 stones made of dolerite, a very hard basalt from the Preseli Mountains in southwest Wales. Because of their bluish shimmer, the megaliths of this material are also called bluestones. Their height reaches up to 2.8 m (towards the open legs it decreases to 70 cm), and their shape is the typical conical one of the Stone Age obelisk. A distinctive feature is that the two stones to the left and right of the base of this horseshoe have a cross-section that corresponds to the geometry of a tongue-and-groove joint used in carpentry.

- The large horseshoe includes the small one. It consisted of ten sandstone blocks (so-called sarsen), each connected in pairs by a third at their top. With a height of over 5 meters, they weighed up to 50 tons and must have been moved on sledges pulled by an estimated 250 men, on inclines by up to 1000 men. Alternatively, the use of draft animals is discussed.

- The mighty Sarsen horseshoe is followed by the circle of originally 60 bluestones. On average, they are a good deal smaller than those of the bluestone horseshoe and are cylindrical in shape (instead of conical).

- The formation of this bluestone circle is surrounded by another circle, again constructed of sarsen: originally 30 in number, about 4.5 m high and connected by 30 laid blocks in such a way that a closed ring structure was formed.

- The sacrificial stone, whose name is also misleading because it is easily confused with the altar stone, is currently located in the middle of the northeastern opening of the ring wall, in a sense in the exit of the complex. The audio guide that leads visitors around the monument states that this stone probably stood upright, and that its red stains are not blood (which would have long since weathered and washed away), but iron oxide inclusions. The naming "sacrificial stone" is therefore more than questionable.

- The Heelstone or Friars Heel, in German called "Fersenstein", stands relatively far outside the Ringwall.

- The four station stones.

Other special features:

- The Aubrey holes (56 pieces)

- The Y and Z holes (29 and 30)

On behalf of English Heritage, laser scans were made of the surfaces of all 83 surviving monumental stones at Stonehenge. A total of 72 previously unknown engravings were discovered. 71 of them show axes (up to 46 cm tall), one a dagger. The site resembles the stone circles in northern Scotland known as the Ring ofBrodgar.

The sacrificial stone

The heelstone or heel stone

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Stonehenge?

A: Stonehenge is a prehistoric World Heritage Site of megaliths located eight miles north of Salisbury in Wiltshire, England.

Q: When was Stonehenge built?

A: Stonehenge was built between 3100 BC and 1550 BC.

Q: How long did it stay in use for?

A: Stonehenge stayed in use until the Bronze Age.

Q: What does the monument consist of?

A: The monument consists of a henge with standing stones arranged in circles.

Q: Is it an important site?

A: Yes, it is probably the most important prehistoric monument in Britain.

Q: Has it attracted visitors over time?

A: Yes, Stonehenge has attracted visitors from very early times.

Q: Where is Stonehenge located?

A:Stonehenge is located eight miles (13 kilometers) north of Salisbury in Wiltshire, England.

Search within the encyclopedia