Stereotype

![]()

This article is about the conception image - for other meanings, see Stereotype (disambiguation).

A stereotype (Ancient Greek στερεός stereós, German 'fest, haltbar, räumlich' and τύπος týpos, German 'form, in this kind, -artig') is a description of persons or groups that is present in everyday knowledge, is memorable and pictorial and refers to a fact that is claimed to be typical in a simplified way. Stereotypes are at the same time relatively rigid, supra-individually valid or widespread images.

The term was introduced by Walter Lippmann in 1922. His work Die öffentliche Meinung (Public Opinion) was groundbreaking for stereotype research. In his understanding, the stereotype is defined as "an epistemological-economic defence against the necessary expenditure of comprehensive detailed experience". Lippmann understands stereotypes as "solidified, schematic, objectively largely incorrect cognitive formulas that have a central function of facilitating decision-making in processes of coping with the environment and the world around us".

In contrast to an (outdated, grid-like) cliché, stereotypes are purely related to persons (groups). In contrast to prejudice, which expresses a general attitude, stereotypes are part of an unconscious and sometimes even automatic cognitive assignment; they can also be meant positively.

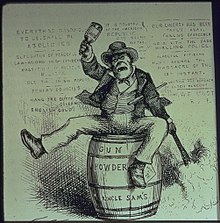

Stereotype of an Irishman: sitting on a powder keg, spouting slogans and drinking rum. American caricature by Thomas Nast published in Harper's Weekly in 1871.

Language use and term usage

The stereotype, like the cliché, comes from a technical term in printing technology and refers to repeated, prefabricated print texts. Stereotypes can be verbalised, they allow the associated complex content to be quickly made present simply by naming the stereotypical term. The categorisation of people on the basis of certain characteristics (e.g. hairstyle, skin colour, age, gender) is a completely normal, fast and almost automatic process for people. Automatic stereotypes are of great interest in the field of social cognition. The term, which is broadly and interdisciplinarily applied, is not uniformly defined in terms of an exact operationalization. Related terms in the word field include prejudice - stereotype - schema - frame - and swear word. Image, on the other hand, which first appeared in the 1950s, concerns a more ephemeral but broader pictorial conception of a group or person. The image is built up through one's own experiences, it must also be cultivated by the image bearer; the stereotype, established on the basis of a few words and aspects, belongs to the public consciousness and is part of socialisation.While Lippmann and his successors used the term stereotype in a pejorative sense, as a factually unfounded and socially harmful idea, today's stereotype research emphasizes the cognitive component of stereotypes. It has been shown that stereotype accuracy, that is, the correspondence between stereotype and reality at the group level, is very high. Studies by Lee Jussim, Thomas R. Cain and other researchers in the USA showed an average correlation of stereotypes with reality based on empirical findings (psychological measurements, demographic and sociological data) of r = 0.7 for ethnic stereotypes (blacks, whites, Asians) and of r = 0.75 for gender stereotypes. This implies a moderate to strong statistical correlation of stereotypes and reality. The effect of agreement with reality on stereotypes is greater than that of subject bias or the effect of self-fulfilling prophecy. Stereotype accuracy is greater than that of individuals' assessments of ethnic groups or gender, or than the predictive power of social psychological theories.

Social science use

The most common use of the term is in a social science context. Here, stereotypes are based on delimitation and the formation of categories around groups of people to whom complexes of characteristics or behaviours are attributed. This clearly distinguishes them from schemata that do not primarily contain social information (e.g. prototypes). Stereotypes (in contrast to sociotypes) are also characterised by the fact that they often caricature and sometimes falsely generalise particularly distinct and obvious characteristics. Such a simplified representation of other groups of people greatly facilitates everyday interactions with unknown persons. Stereotypes triggered by external characteristics (e.g. age, clothing, appearance, gender) serve as reference structures for expected and anticipated behaviour (→ self-fulfilling prophecy). However, the simplification thus ensured also has disadvantages and can in part manifest social inequalities. As soon as characteristics such as gender or skin colour are associated with negative evaluations that clearly limit the interaction possibilities of people in many areas of life, we speak of prejudices.In psychology, behaviors or movements are referred to as stereotypes, which are repeated frequently and usually seemingly meaninglessly, regardless of the specific environmental situation.

In contrast to this are prejudices - on the one hand as abstract-general prejudices, on the other hand as attitudes towards individuals. Stereotypes, on the other hand, do not per se contain a (negative or positive) evaluation; they reduce complexity and also offer possibilities for identification.

Inspired by postcolonialist studies, psychology and other social sciences are now discussing the extent to which scientific concepts can also contribute to problematic stereotyping and prejudice due to their complexity-reducing function. Examples of this can be found in comparative cultural studies, in which, for example, a blanket distinction is made between so-called "individualistic" and so-called "collectivistic" cultures, and these are marked and differentiated on the basis of further supposed "national characteristics" or "cultural features". Corresponding distinctions can also arise in science from socio-historically grown and often insufficiently reflected ethnocentric views.

Search within the encyclopedia