Split, Croatia

This is the sighted version that was marked on June 16, 2021. There is 1 pending change that needs to be sighted.

![]()

This article is about the city in Croatia. For other meanings, see Split (disambiguation).

Split [split] (Italian Spalato, originated from Greek ἀσπάλαθος, aspálathos) is the second largest city in Croatia. It is the largest city in southern Croatia and is therefore popularly considered the "capital of Dalmatia", although it has never been officially granted this status. The city is the administrative seat of Split-Dalmatia County (Croatian: Splitsko-dalmatinska županija), which covers the central part of Dalmatia. Split had about 167,000 inhabitants in 2011.

Split is an important port city and the seat of the Catholic Archdiocese of Split-Makarska. Split is also home to a university. The origins of the city can be traced back to Diocletian's Palace. The city centre of Split, including Diocletian's Palace, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1979.

Centre and Old Town with the Riva Obala Hrvatskog narodnog preporoda (city view from Trg Franje Tuđmana square to the Cathedral tower)

Origin of the name

The city has undergone several name changes in the course of history. Thus one comes across Aspalathos/Spalatos (gr.), Spalatum, Spalato (Italian), Spljet, Split. There are different etymologies to the word. One assumes that the name of the city comes from the plant thorny broom (Greek = Aspalathos, Croatian = Brnistra). Others say that the name is a derivation from the Latin word for "palace", lat. = Palatium, or from the Italian word Spalato (= palace). Another theory comes from the word Spalatum (from Latin Salonae Palatium, in German: Der Palast von Salona, Croatian Solin), the former cultural hub of the inhabitants of Dalmatia. However, the city of Solin, probably the hometown of Emperor Diocletian, was destroyed during the Avar storm and lost its importance to the neighboring city of Split.

History

Prehistory

Finds of stone objects from the Middle Paleolithic (about 50,000 BC) from the Mujina Cave above the Polje of Kaštela already testify to the presence of people in this area. The first castle-like settlements on the hills are attested from the Copper Age, and in the Bronze and Iron Ages Illyrian Dalmatians inhabited the area around present-day Split, after whom the whole region of Dalmatia was named.

Greek colony (from 4th century BC), Diocletian's palace

Split was founded in the 4th or 3rd century BC as the Greek colony of Aspalathos or Spálathos. It was settled from Issa, today's Vis, which had gained autonomy from its mother city Syracuse since 367 BC, and now founded its own colonies.

To the north of the city lies the Roman settlement of Salona. The most important building there is the arena, which has since been destroyed.

The nucleus of today's Split is wrongly considered to be Diocletian's Palace. Emperor Diocletian had it built around 300. After his death around 312 and that of his wife Prisca (probably 315), the Roman Empire used the palace as an administrative seat, barracks and as a production site (textile production in a gynaeceum) for the military apparatus, which was increasingly converted to self-sufficiency in view of the crisis-ridden economy.

The actual residential wing was used on various occasions by emperors as a place to stay or as a place of exile for disgraced emperors. Galla Placidia stayed here in 424 with her son Valentinian III. Before he went to Italy to overthrow the usurper John. In 461, the general Marcellinus used the palace while serving as magister militum Dalmatiae. The overthrown emperor Glycerius occupied the palace from 474 until his death in 480, the same year his successor Julius Nepos succumbed to a poison attack in the palace. With the decline of the Roman Empire, the palace also fell into disrepair, serving only as a military post.

New foundation (7th century), between Croats, Byzantium, Venice and Hungary.

In the early 7th century, Avars and Slavs raided and destroyed the city of Salona. The escaped and surviving Salonitans found refuge in the well-fortified palace of Spalatum and set up home there. They turned the palace complex into a city. Today, the former palace still forms the eastern part of Split's old town and is filled with shops, markets, squares and the Cathedral of St. Domnius, which in ancient times was the mausoleum of the emperor and empress Diocletian and Prisca and formed the centre of the palace. The palace could never be taken by the invading barbarians, so Spalatum - like many other Dalmatian towns - preserved itself as a haven of the late Roman world - while invading peoples took the hinterland.

At the latest from the Peace of Aachen (812), Spalatum was part of the Byzantine subject of Dalmatia. Slavic principalities arose in the hinterland. The archbishopric of Spalatum extended over the held territory of the city as well as the Slavic principalities of the hinterland. Tomislav, who had united several principalities as king of the Croats, attended synods in Spalatum between 925 and 928 as the representative of the hinterland; it was he who approved and thus helped to enforce the claims of the diocese of Split against those of the bishop of Nin. The bishopric included both the Byzantine subject of Dalmatia and the Slavic hinterland.

Emperor Basileios II of the weakened Eastern Roman Empire gave Spalatum and other Byzantine possessions in Dalmatia to Croatian King Stjepan Držislav in 986 for his successful help in repelling the Bulgarian invasions. Several times the city now served as the Croatian capital. When the Republic of Venice under Doge Pietro II Orseolo began to extend its power to the residual Roman territories from which Byzantium had withdrawn, Spalatum - like other Dalmatian cities and islands - accepted Venetian suzerainty, which the city enforced by mustering a strong fleet. This earned the doge the additional title of Dux Dalmatiae (Doge/Duke of Dalmatia), but the Venetian suzerainty remained insecure.

In 1015, King Krešimir III obtained Spalatum and other cities for Croatia, supported by Emperor Basileios II. However, around 1016/18 the doge Ottone Orseolo again succeeded in enforcing a temporary supremacy, the recognition of which was sworn by the Dalmatian cities as two decades before. From 1024 to 1068, however, Spalatum was again subject to Byzantium. The government of the almost autonomous municipality was taken over by the prior of the archbishop, who until the 12th century always came from the city.

Once again, Croatia, which had freed itself from Byzantine dominance, managed to assert indirect rule over the city. After the Normans invaded Spalatum in 1074, the Republic of Venice expelled them, but it could not hold the city, so from 1076 King Demetrius (Dmitar Zvonimir) of Croatia captured Spalatum and other Dalmatian cities for his kingdom. With his death in 1089, Byzantium again took over before Venice asserted itself in 1097. In this period the municipality becomes tangible as a comune.

Commune (from the middle of the 12th century)

In 1105 Spalato - like Traù (Trogir) and Zara (Zadar) - shook off Venetian domination when King Koloman of Hungary, Dalmatia and Croatia guaranteed the towns extensive autonomy, protection from foreign powers and trading privileges in his kingdom. His successors confirmed and extended the liberties of the Dalmatian cities, so that although they recognized the king as their head, they were otherwise not part of the kingdom, but autonomous. Influence was exerted indirectly, through the occupation of the archbishop's seat. The comune, which can be traced back to the middle of the 12th century, was now no longer presided over by a prior, but by a comes. The commune formed its own organs, the inhabitants with civil rights, the cives, elected a consilium (town council) and a comes, later called podestà. Judges and currency (bagatino and spalatino) were subject to municipal laws. From 1165 to 1180, Emperor Manuel I succeeded for the last time in reclaiming Spalato for his empire. The importance of trade increased in this period, and at the same time treaties led to a juridification. This was the case, for example, with treaties with Pisa, Piran and Fermo. From the beginning of the 13th century, Croatian greats exercised city rule. In order to solve internal conflicts, the municipality appointed a podestà for the first time in 1239, who came from Ancona. Now a council constitution was created, of which a version from 1312 has survived.

In 1242, a Tartar invasion reached the gates of the town, but Spalato held out and gave refuge within its walls to the defeated King Béla IV of Hungary, as well as Croatia, Dalmatia and Rama. The city competed with Traù (Trogir). Feudal princes of the hinterland had themselves naturalized in Spalato, but also carried their feuds to the town. Prince Domald of the Klis fortress above the town attacked Spalatians travelling in the hinterland and tried to blackmail the town by cutting off its supplies from the countryside. In 1334 the circle of councilable families was closed. The part of the town to the west of the old palace was included in the town wall after 1312.

Podestà Gargano de Arscindis, elected for three terms from 1239, again consolidated the institutions of the Comune. The piazza in the medieval extension of the city is first mentioned by name in 1255 as Platea sancti Laurentii (today Narodni trg). In the diadochal struggles following the extinction of the Árpád dynasty (1301), Venice was able to regain Spalato (1327). The city subordinated itself to Venice, which now appointed and dispatched the Comes. He was both chief official of the city and representative of the Doge.

The city law was codified in 1312 by Perceval of Fermo in the Libro d'oro (Golden Book), which remained in force until 1797. No sooner had a new dynasty prevailed with Louis I and this king defeated Venice in 1357 than it ceded Spalato and the other towns back to Croatia (then in personal union with Hungary) in the Peace of Zadar in 1358.

From 1373, the time of Hungarian suzerainty, comes the oldest preserved stone fragment with the name of the town: "Comune Spalati". On the mainland, the town was able to claim as its own territory the Marjan peninsula and, beyond that, parts of the Kaštela field and Poljica. Already in Klis and Omiš sat Croatian feudal lords who sought to subjugate the rich Spalato. Spalatians were attacked while working in the fields in the countryside of the town, kidnapped to extort ransom, or even sold into slavery. Thus threatened and disturbed in its intercourse with the hinterland, Spalato directed its economy even more toward sea connections. Wood came from the islands, not from the nearby but dangerous mainland; fish was common, but meat was rare on the menu because of the lack of pasture in the land area of the city.

The death of Louis I in 1382 weakened Hungary, so that in 1390 King Tvrtko I seized the town for his kingdom of Bosnia. But already his successor Stjepan Dabiša had to recognize the suzerainty of Sigismund of Luxembourg, King of Hungary-Croatia (later also Holy Roman Emperor) in 1394 and cede Spalato to him. Two years later, after the lost Battle of Nicopolis, Sigismund sought refuge in Spalato and contacted burgher circles, who in 1398 instigated an uprising against the incumbent councillors. The new council then made peace with Traù.

In 1402, Spalato had to recognize King Ladislaus of Naples, who claimed Dalmatia for himself, as lord, enforced by his viceroy Hrvoje Vukčić Hrvatinić of Dalmatia and Croatia, who henceforth also called himself Duke of Spalato. However, when Sigismund defeated Ladislaus, Hrvoje fell away from him and subordinated himself to Sigismund, who forgave him for partisanship with Ladislaus in 1403. Duke Hrvoje rose to autocratic tyranny, for which reason the commune expelled him in 1413 and no longer recognized him as duke, quelling an uprising of his partisans in the city.

Venetian rule (from 1420), conquest attempts by the Ottomans in the 16th century

Spalato prevented Hrvoje's return by voluntarily submitting to Venice in 1420. On the Platea sancti Laurentii, a Venetian loggia, a Rector's Palace (after the Rectors, the Venetian governors) and a Palazzo del Comune (Town Hall) were built in the 15th century. The latter two were demolished in 1821 due to dilapidation.

After the Ottoman Empire had conquered Bosnia (1463) and finally also Herzegovina (1482), the raids on Spalatians in the land area of the city increased. Although Venice was able to force the Ottomans into peace agreements in various wars (especially the Third Ottoman-Venetian War of 1499-1503), the raids on Spalato and other Venetian protectorates nevertheless continued. Economically, all this led to a stagnation of the economy already in the 15th century.

In 1522, the Ottomans attempted to take the fortress of Klis above Spalato, which was repelled with the support of Archbishop Tommaso de Nigris (Toma Nigris). The Spalatine humanists Marcus Marulus Spalatensis (Marko Marulić/Marco Marulo) and Franciscus Natalis (Franjo Božičević Natalis) underpinned the anti-Ottoman sentiment in the city. Petar Kružić (Peter Krusitsch), captain of the Klis fortress, had resisted Ottoman attacks for more than 20 years when he fell in 1537 in the course of the Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War (1537-1540), and with him the fortress, which henceforth served as an Ottoman outpost for attacks on Spalato. In the course of the Fifth Ottoman-Venetian War (over Cyprus), parts of the land area of the town, including Solin and Kamen (Sasso di Spalato), fell to the Turks in 1571. An attempt to reconquer the city failed.

In the early 1570s, Jews established a Sephardic community in the northwestern part of the palace district; the cemetery on Marjan, established in 1573, still exists today. Daniel Rodrigo, a native of Portugal, founded the city's first banking house in 1572, and Venice granted it duty-free treatment for exports of goods from the Balkans in 1579. The old harbour hospital in front of the southern façade of Diocletian's Palace, originally built for plague sufferers, became the terminal and starting point of caravans to and from the Balkans as a magazine. The lazaretto was also a quarantine area to prevent - following the Venetian model - caravan drivers from carrying diseases into the city proper.

Culture took off and the painters Biagio di Giorgio da Traù (Blaž Jurjev Trogiranin) and Dujam Vušković, as well as the sculptors Bonino da Milano, Giorgio di Matteo Dalmatico (Juraj Dalmatinac) (among others. Palazzo Papalić, now the City Museum), and, somewhat later, the architects Andrea Alessi (Andrija Aleši) and Niccolò di Giovanni Fiorentino (Nikola Firentinac). Marco Antonio de Dominis (Marko Gospodnetić), who became archbishop from 1602, influenced the thinking of the humanists in the city as a philosopher. From 1615, the Franciscan and composer Ivan Lukačić worked as a chapel master at the cathedral.

Plague waves and population collapse, Croatian immigration

The plague carried off 7,000 of the 10,000 inhabitants at the end of the 16th century, and after another epidemic in 1607 only 1,400 Spalatians remained. Further wars (the Sixth Ottoman-Venetian War (for Crete), 1645-1669, and the Seventh Ottoman-Venetian War (the Great Turkish War), 1684-1699) affected Spalato's development and contributed to the decline of Venice and its possessions. At least General Leonardo Foscolo succeeded in 1645 in wresting the fortress of Klis from the Ottomans again, which from then on was able to prevent Ottoman incursions into the land area of the city. However, in 1657, Hersekli Ahmed Paşa once again penetrated the land area to the city's walls. The master fortress builder Alessandra Maglio then built massive bastions and ramparts around the city, as mapped by Giuseppe Santini in 1666.

With the successive pushback of the Ottomans in the early 18th century, the threat also moved territorially far from Spalato's land territory. The city's population grew, and migrants from the hinterland spread Croatian as a vernacular, also encouraged by the Illyrian Academy. Citizens of the town established a business society in 1767 to promote trade, fishing, and agriculture. French scholars developed an increased interest in the city's ancient monuments, and Charles-Louis Clérisseau produced the first modern monograph on the palace in 1764, before Louis-François Cassas produced a series of watercolours in 1782, which, reproduced, found admirers throughout Europe.

France, Austria-Hungary (from 1797)

With the end of the Republic of Venice, brought about by Napoleon in 1797, Austria took over its Dalmatian possessions and so did Spalato. But this did not last long, because in 1806 General Lauriston conquered Spalato for the French Illyrian Provinces (1807-1813). In 1806 and 1807, on the orders of Auguste Viesse de Marmont, the demolition of the ramparts and bastions began, which was completed in the following Austrian period.

In 1813, the Empire of Austria conquered Illyria and transformed it into the Kingdom of Dalmatia (later crown land) within the Habsburg Monarchy. Italian was the official language and school language. In 1817 the Classical Gymnasium opened, and after the visit of the imperial couple Franz I and Karoline Auguste the following year, the imperial governor decreed monument protection for the city's architectural monuments, and archaeological excavations began in Salona, the finds of which were displayed from 1821 in the new Archaeological Museum, one of the oldest of its kind. Nevertheless, Governor Rehe ordered the demolition of the late Gothic buildings in Piazza San Lorenzo (Narodni trg) in the same year.

During the imperial reform to the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1867, Spalato remained with Dalmatia in the Cisleithanian half of the empire. The town became the seat of the district governorate of the district of the same name. In 1877 it was connected to the railway, which was extended to Knin in 1888, thus providing access to the European railway network. Spalato was a garrison town of the Imperial and Royal Army. In 1914 the III Battalion of the Hungarian Infantry Regiment No. 31 was stationed here.

Between 1860 and 1880, Italian-speaking autonomists dominated city politics under Podestà Antonio Baiamonti (Antun Bajamonti); they promoted the expansion of the city's infrastructure (water supply, harbor expansion, gas lighting), but otherwise refused to create educational and cultural opportunities for the growing Croatian population.

In 1882, the Croatian nationalist People's Party won the local elections. Croatian now became the official language of the city and the language of schooling in Split. The offer of Italian-language schools was severely limited. However, in official use on an Empire-wide level, the Italian designations, i.e. also Spalato as the name of the city, remained binding until 1918.

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as of 1918

After the end of the First World War, Split became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. During the term (1918-1928) of mayor Ivo Tartaglia, Split underwent significant changes. After Zara (Zadar) and offshore islands (together the Italian province of Zara) were granted to Italy in the border treaty of Rapallo in 1920, Split developed into the centre of Croatian Dalmatia.

Many Croatian Dalmatians from the province of Zara settled in Split, which exacerbated the housing shortage there, also due to the interruption of construction activity during the First World War. So Tartaglia pushed ahead with the development of Split. At the international competition for the development plan of Split in June 1923, the German architect Werner Schürmann, then based in The Hague, won one of the two second prizes; the first was not awarded. Schürmann was awarded the contract and came to Split for eight months from September 1924 to work out the regulatory plan en détail, which was executed from 1925.

The historical centre, the palace district and the medieval extension of the old town were to be surrounded on the land side by a green belt with a bypass road from the eastern Bačvice Bay to the western Marjan Hill. Beyond the old built-up area, according to the plan, the Marjan peninsula was opened up for development and construction in the following years. In the course of this, the actual Mount Marjan itself was reforested and became a recreational area in the city. A new commercial port was built at Kaštela Bay in the north of the peninsula, near the ancient Salona (Solin).

The new railway station was built near the new port, new main roads connected both with the old port in the south of the peninsula. The architect Alfred Keller won the tender for the renovation of the south façade of Diocletian's Palace. The existing porches were reduced, and the Riva waterfront street in front of it was developed as a promenade and planted with palm trees. The old railway station, near the Porta Argenta, was demolished and its rail connection dismantled in order to reclaim the land for the city expansion. The Split County did not approve the plan until 1928.

During these years, the sculptor Ivan Meštrović acquired the former fort of Capogrosso (Croat.: Kaštelet), converted it for the exhibition of his sculptures and built himself a villa in Meje, which he bequeathed to the state when he emigrated to the USA in 1947 (today the Meštrović Gallery). In 1931, a new Yugoslav building law was enacted, requiring adjustments to Schürmann's plan that lasted until 1940.

World War II, Yugoslavia

During World War II, Italian troops attacked Yugoslavia, including the invasion of Split on April 6, 1941. This secession from Yugoslavia was formally recognised by the Treaty of Rome of 18 May 1941, in which the Independent State of Croatia renounced Split. The Italian Governatorato di Dalmazia was created there. Split remained Italian until 1943, followed by German occupation from September 1943, which lasted until June 1944. With Italy's surrender in September 1943, Tito's partisans succeeded in occupying the city, and many of the Italian soldiers switched to their side.

Allied air raids in September destroyed, among other things, the northern façade of Diocletian's Palace, the historic military hospital at the old port, and the Benedictine monastery of St. Euphemia. However, the Wehrmacht occupied the city and formally handed it over to the Ustasha, Croatia's fascist government. In the Trilj massacre, many Italians were massacred by the SS. At times the city was bombed by both the Allies and the Axis powers. On October 26, 1944, partisans finally captured the town. As late as February 12, 1945, the German Navy attacked the city's harbor, where six German demolition boats severely damaged the cruiser HMS Delhi.

After the war, Split became part of the Croatian Republic within Yugoslavia. In 1936-1937, Milorad Družeić (1911-1997) had taken over the detailed planning for Schürmann's regulation plan, and in 1950 he developed the spatial development plan for Split.

Since 1991 Split belongs to the independent Republic of Croatia.

Croatian War 1991

See also: Croatian war

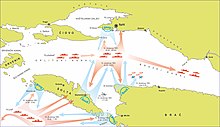

At the time when Croatia declared its independence, Split was an important garrison city of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) with soldiers from all over Yugoslavia and the headquarters of the Yugoslav Navy (JRM). The political situation led to tensions between the Serb-dominated JNA and the Croatian National Guard for months, especially from the summer of 1991 (the beginning of the war in Slovenia and Bosnia). The Croatian Navy (HRM) was not yet operational at sea at that time and started to build up coastal artillery batteries (OTB) on the mainland and on the islands of Šolta and Brač respectively. As a countermeasure, the JRM imposed several naval blockades, shelling targets on land. On 14 November, the JRM's tactical group "Kastela" formed up with several ships in the Splitski Channel between the islands of Šolta and Čiovo, and with fewer ships in the south-east of Split and south of Šolta, respectively. The most serious incident occurred at dawn on 15 November 1991, when the JRM frigate Split fired shells at the town and its surroundings. Property damage was not extensive, but there were six fatalities. Shelling was not of military targets, but of the old town, the airport and an uninhabited area above the town. Many sailors in the JRM were Croats. Some refused to attack Croat civilians and were detained. In addition to Split, targets were also shelled on Brač and Šolta, where damage occurred in Gornje Selo. However, the much stronger JRM could not prevail against the Croatian forces. The battle is considered to have set the tone for the rest of the war on the coast. The JNA and JRM evacuated their entire forces from Split in January 1992. In the Dalmatian War, a total of 692 soldiers from Split disappeared or died, 58 of them members of the Navy.

At the end of July 1995, the "Franco-German Field Hospital" was set up nearby to provide medical care for 12,500 soldiers of a multinational United Nations Rapid Reaction Force protecting UNPROFOR on Mount Igman near Sarajevo.

In 2004 the town celebrated its 1700th anniversary.

Patrons of the city are:

- Saint Anastasius (sveti Stašo),

- Saint Domnius (sveti Duje),

- Saint Rainer of Split (sveti Arnir) (? - 1180), an archbishop of Split who was stoned to death nearby.

Battle in the Split Channel on 15 Nov. 1991

German soldiers taking down the partisan flag and raising the swastika flag on the Marjan in September/October 1943.

German troops entering Split with armoured reconnaissance vehicles at the corner of Corso Guglielmo Marconi / Riva A Hitler in September 1943.

Spalato district authority - seal stamp

The Municipal Theatre of Croatian Language built in 1891-1893 (today: National Theatre)

Procurative, built in 1858/1859 by Giovanni Battista Meduna

.jpg)

Venetian Loggia, today Ethnographic Museum.

Peace of Zadar Kingdom of Hungary Kingdom of Croatia Bosnia banana community Duchy of Austria Patriarchate of Aquileia Republic of Venice Republic of Ragusa Serbian Empire

The statue of Bishop Gregory of Nin (900-929) by Ivan Meštrović on the square in front of the Porta Aurea

The port of Split

.jpg)

View from the Campanile over the western part of the old town to the Marjan Hill

Salona Archaeological Park

Search within the encyclopedia