Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

Training of franquist soldiers

by the "Condor Legion

Military operations during the

Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Gijón - Oviedo - Alcázar of Toledo - Mérida - Badajoz - Guipúzcoa - Mallorca - Sierra Guadalupe - Talavera de la Reina - Madrid - Road to Coruña - Málaga - Jarama - Guadalajara - War in the North (Durango, Guernica, Santander) - Brunete - Belchite - Teruel - Cabo de Palos - Aragon - Ebro - Catalonia

The Spanish Civil War (also known as the Spanish War) was fought in Spain between July 1936 and April 1939 between the democratically elected government of the Second Spanish Republic ("Republicans") and the right-wing putschists under General Francisco Franco ("Nationalists"). With the support and after military intervention of the fascist and nationalist allies from Italy and Germany respectively, the alliance of conservative military, Catholic CEDA, the Carlists and the fascist Falange won. This victory was followed by the end of the Republic in Spain and the Francoist dictatorship (1939-1976), which lasted until Franco's death in 1975.

Background

Causes

Causes for the outbreak of war can be found in the extreme socio-political and cultural upheavals in Spanish society as well as in regional autonomy aspirations, for example in the Basque Country and Catalonia. Spain suffered numerous violent conflicts from the mid-19th century onwards that remained unresolved. They increased in number and intensified when, after the defeat in the Spanish-American War in 1898, the prestige of the old institutions was largely lost. The few supporters of the Second Spanish Republic had neither succeeded in remedying the serious social grievances nor in countering the advocates of an authoritarian state order.

Spain was affected by several structural problems before the civil war:

- the completely underprivileged position of the rural and industrial working classes, some of whom were striving for radical social upheavals

- the contradiction between partly feudal structures in rural areas and the far advanced industrialisation in urban centres like Barcelona or Madrid

- the dispute over the cultural monopoly between the Roman Catholic Church and the secular liberal republican forces

- the fierce resistance of the Basques and Catalans to emancipate themselves from central government

- the lack of government control over the military, its alienation from large segments of society, and its role as a "state within a state."

In recent Spanish history, peaceful solutions have hardly been a tradition. Clerical-monarchist, republican, bourgeois-liberal, socialist, communist and fascist groups were irreconcilably opposed to each other for a long time. Because of the economic crisis in Spain and the changing situation in Europe due to the rise of fascism, the situation became visibly worse.

Previous story

After initial enthusiasm, the Second Republic, founded in 1931, quickly lost support. The traditional elites from the times of dictatorship and monarchy feared a threat to their privileges and cultural self-image. The secular orientation of the first government and the attacks on church institutions inspired by a radical anticlericalism strengthened them in this attitude. They opposed all reforms that held out the prospect of improving general living conditions.

The initial euphoria of the workers towards the republic also quickly cooled. After the social reforms proved unworkable and the new right-wing government took a hard line in 1934, organized workers saw in the new parliamentary form of government nothing more than a continuation of the old policy of oppression.

The anarcho-syndicalist CNT had fought the Republic almost from the outset, and on 8 January 1933 and 8 December 1933 undertook two attempts at insurrection, which collapsed immediately; the previously reformist socialist trade union UGT, disappointed with the government alliance with the Republicans, switched to a revolutionary course from 1933 onwards and propagated the dictatorship of the proletariat. However, some researchers doubt whether these were more than "empty revolutionary slogans" with which the leading socialists reacted to pressure from below. Significant sections of the socialist party PSOE clearly continued to rely on cooperation with the liberals.

The Republicans, who set out to transform Spain, implemented many important reforms only half-heartedly. Large sections of the bourgeoisie nevertheless feared a domination of the working class and were therefore prepared to support a dictatorship. Added to this were the efforts of the Catalan and Basque bourgeoisie to leave the Castilian-dominated central state.

On August 10, 1932, a first military coup took place under General José Sanjurjo, centered in Seville, which was poorly executed and thwarted by a general strike. The pardon of Sanjurjo, who was initially sentenced to death, and the light prison sentences for some other officers involved, were understood by the Right as an incentive to prepare the next attempt better and, above all, for the long term. As early as the end of September 1932, radical right-wing monarchists of the Acción Española, together with some general staff officers, formed a committee operating from Biarritz, France, to prepare a new coup through the conspiratorial networking of anti-republican officers (who had been organizing themselves in the conspiratorial Unión Militar Española since late 1933). In addition, the committee promoted the systematic journalistic delegitimization of the Republic, which it portrayed as the product of a "Judeo-Masonic-Bolshevik" conspiracy. It also infiltrated paid provocateurs into anarchist organizations to organize the all-important "breakdown of law and order" as a pretext in the immediate run-up to the planned coup itself.

Even independent of these efforts, there was a radicalization of right-wing discourse between 1931 and 1936, as British historian Paul Preston pointed out in 2012. A variety of newspapers, journals, and books-including the widely read Orígenes de la revolución española (1932) by the Catalan priest Juan Tusquets Terrats-argued that leftists were "neither truly Spanish nor at all human" and that the "extermination of leftists should be considered a patriotic duty." Carlist and fascist writers in particular identified the entire Spanish labor movement with the medieval Muslim conquerors and called for a "second Reconquista," adding an additional "racist dimension" to the attacks on the left. José María Gil-Robles, the leader of the "moderate" Catholic conservative CEDA, also used this rhetoric, which sought to discredit the entire left as "un-" or "anti-Spanish." This potentially eliminatory aggressiveness merged, especially in the rural areas of the South, with the hatred of the large landowners for the agricultural workers, whose traditional fatalistic subservience to the aristocracy had largely disappeared in the early years of the Republic, giving way to openly expressed demands for land and better pay. However, the militant rejection of the Republic's anticlerical and social-reform legislation, shared by the entire old establishment, was concentrated in the Spanish officer corps (and here especially among the africanistas, the officers of the colonial army) - not least because the left-wing parties planned to adjust the size of the traditionally notoriously oversized officer corps to the actual size of the army. The "instinctive hostility [of the officers] to the Republic" was also ideologically masked in the run-up to the civil war with the idea of a "Judeo-Masonic-Bolshevik conspiracy." Franco was an avid reader of Tusquets' writings and subscriber to the journal of Acción Española, and General Emilio Mola, the actual military planner of the coup of the summer of 1936, had been participating in this debate since 1931 with his own publications. Mola ensured that the eliminatory dimension of this discourse also determined the concrete preparations of the conspirators: "The repression staged by the military rebels was a carefully planned operation aimed at eliminating those, in the words of the coup planner General Emilio Mola, 'without scruple or hesitation [who] do not think like us.'"

In the fall of 1933, the first coalition under Prime Minister Manuel Azaña collapsed, to be succeeded by a centrist government under Alejandro Lerroux, tolerated and elected by the right-wing parties. It amnestied the putschists of 1932 and those convicted of crimes during Miguel Primo de Rivera's dictatorship, reversed the "meager" social and secular reforms, and aggravated the situation of wage earners. The left and the liberal republicans took this as a declaration of war. When the CEDA entered the government with three ministers at the beginning of October 1934, the UGT proclaimed a general strike, but this was crushed by the government with mass arrests as quickly as the attempt to proclaim an independent Catalonia in Barcelona. In Asturias, however, the strike - on the initiative of the workers and against the resistance of the union officials - took on the features of an open revolt. The Asturian miners' strike of 1934 (also called the "October Uprising") gave the first taste of civil war, with hundreds of deaths - the government declared martial law. Under the high command of Francisco Franco, who later became dictator, the uprising was brutally crushed. There were at least 1,300 deaths, 78% of them civilians. There followed a widespread wave of arrests, including top liberal and socialist politicians, and censorship that affected left-wing newspapers. The CEDA, led by José María Gil-Robles, a Catholic rallying movement that in parts sympathized with European fascism, surged to power but failed against President Zamora. Gil-Robles, who served temporarily as minister of war under Lerroux, nevertheless laid the groundwork for the rise of the group of radicalized military officers around General Franco, who prepared the conspiracy to rebel by promoting them to high posts. The Falange Española, founded in 1933 by the son of the ex-dictator Primo de Rivera, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, developed during this period from a political splinter group into an equally serious militant factor.

By the end of 1935, the second coalition of Lerroux's Radicals and the CEDA was also at an end due to internal squabbles and a financial scandal. In order to use the majority vote for themselves this time, Socialists, Republicans, liberal Catalanists, the Stalinist Partido Comunista de España (PCE) and the Communist Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) formed a Popular Front alliance, the Frente Popular. They were supported by the Basque nationalists and the anarchists, who this time did not formulate an electoral boycott. Against them stood the Frente Nacional made up of CEDA, monarchists, a landowners' party and the Carlist. In between were the parties of the center, which had little more significance.

On 16 February 1936, the Popular Front won the elections; the parliamentary opposition also acknowledged its victory. According to the most cited data of Javier Tussell, the parties of the left Popular Front received 4,654,116 votes in the first round, those of the right National Front 4,503,505 votes and other parties (including the Centre, Basque Nationalists and the Partido Republicano Radical) 562,651 votes. After the second round of voting on 1 March and the action of a mandate verification commission set up by the new government, this led to the following distribution of seats: Popular Front 301 seats (of which PSOE 99 and Izquierda Republicana 83), National Front 124 (of which CEDA 83), others 71. The information given by various historians on the results of the vote count, which were not published in detail at the time, but not on the distribution of seats, differs to some extent today. Some conservative historians additionally emphasize that irregularities in the vote count influenced the election result and the distribution of parliamentary seats in favor of the Popular Front. However, it was the right-wing CEDA that was deprived of several mandates by the Audit Commission due to blatant electoral fraud in the provinces of Salamanca and Granada.

With the victory of the Popular Front, the Republic had ceased to exist for sections of the right. Notwithstanding the resumption of the reform program of the new government under Azaña, formed without a single Socialist member, there were spontaneous occupations of land, strike activity increased sharply, and street fighting between extremists of both political camps, sometimes violently suppressed by armed forces of order, increased markedly. The fascist Falange exercised targeted terror, against which the state proved powerless. The spectre of a communist takeover in Spain was conjured up by the right-wingers, who were no longer willing to put up with many of the government's decisions favouring the radical left.

Meanwhile, the officers planned the coup almost publicly. Their activities were largely ignored or only lightly punished by the Azaña government. In fighting the coup plotters, it would have had to arm the unions, which it tried to avoid as much as possible. The new government had exiled many officers suspected of anti-republicanism to remote bases in the Spanish islands and Spanish Morocco, unwittingly aiding their conspiracy and creating an impregnable power base for them. The colonial troops stationed in Spanish Morocco were among the most effective and feared opponents of the Republicans in the later Civil War. In Spain itself, the machinations of the conspirators were observed by officers of the secret anti-fascist society UMRA, the Unión Militar Republicana Antifascista.

At the height of the unrest, on July 13, the monarchist opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo was assassinated by members of the Guardia de Asalto and the Guardia Civil in a revenge action for the death of a UMRA member. His death prompted the Carlists to support the coup with their paramilitary units.

When the uprising began, it was mainly the workers who resisted. Where they were successful, they responded with a revolution, carried mainly by the anarchists. This saved the republic's existence for the time being. The coup turned into a civil war, which soon became entangled in the international web of relations in Europe, which was to have a decisive influence on the course of events.

military coup

Initiated by a military revolt in Spanish Morocco, the military coup d'état against the Second Spanish Republic began on July 17, 1936. The coup plotters, who from the beginning found sympathy among parts of the Spanish military in the Iberian Peninsula, relied mainly on the Spanish colonial forces in Spanish Morocco (the Regulares, an army of Moroccan mercenaries, as well as the Spanish Legion) and hoped to quickly gain control of the capital Madrid and all important cities.

According to General Emilio Mola's plans, the insurrection in Spanish North Africa was originally to begin at 5 a.m. on July 18, and that on the mainland 24 hours later. The plans were discovered in Melilla at noon on July 17, necessitating an early strike. The town of Melilla was brought under insurgent control before the end of July 17. Shortly after 6 a.m. on July 18, Franco addressed the army in a radio message, giving the signal for the uprising. By this time almost all the military bases in Morocco were under control of the putschists, except for the air base at Tétuan, which soon fell. The Canary Islands, where Franco was in command, were also secured for the insurgents that day. But the left on the island of La Palma was able to maintain the republic there for another week during Semana Roja.

The nominal leader of the military coup was General Sanjurjo, who had already failed with a coup in 1932 and was therefore in exile in Portugal at the time. On the return flight from exile, the general suffered a fatal accident on July 20, which led to a power vacuum among the National Spaniards. This was filled by a triumvirate of Generals Mola, Franco and Queipo de Llano.

The Madrid government learned of the uprising in North Africa on the evening of 17 July, but reacted appeasingly, since no unit on the mainland had yet joined it. Offers of help from the CNT and UGT and their requests to issue arms to them were firmly rejected by Santiago Casares Quiroga on 18 July, and the population was told to go about their normal business. Casares Quiroga still believed that General Queipo de Llano would not take part in the insurrection and would restore order in Andalusia. In fact, that day Queipo had captured the important city of Seville and the military there for the putschists. That night the unions called a general strike.

A race began between the putschists and the workers' organizations to secure the most important cities on the coast of southern Spain from Spanish Morocco. The attitude of the local civil governor, as well as the local Guardia Civil and the Asaltos, was often decisive. The Republicans achieved successes in Málaga, Almería and Jaén, for example, while the putschists fell into the hands of Cádiz (with its naval base), Jerez, Algeciras and La Linea. Prime Minister Casares Quiroga resigned on July 19 after his misjudgment of the situation became apparent. His successor, Diego Martínez Barrio, sought to end the insurgency by promising the insurgents a political say and the restoration of law and order, which the conservative opposition had demanded in vain in parliament over the previous five months. However, this was replaced after a few hours by the more radical José Giral when efforts at mediation failed. The new government immediately ordered the fleet to sail to the Straits of Gibraltar to prevent the Africa Army from crossing. The army was disbanded by decree, and arms were distributed to the workers' organizations.

In the days that followed, every soldier was faced with the decision of which side to fight for. 80% of the lower and middle officer corps, the majority of non-commissioned officers, but only four division generals, decided in favour of the coup. The Nationalists were often able to prevail by arresting local military leaders and governors loyal to the Republic, most of whom were immediately shot. In many cities, including Madrid and Barcelona, there were sieges of local barracks by workers' militias. By the end of July, the putschists gained control of a broad strip of territory in northern Spain from the Carlist region of Navarre in the east to Galicia in the west, with the exception of the coastal region from the Basque country to Asturias. In the south, the Nationalist territory extended to Saragossa, Teruel, Segovia, Ávila, and Cáceres. In addition, the cities of Seville, Córdoba and Granada were added as (soon to be joined) enclaves in southern Spain, as well as Oviedo and Toledo in the north, along with the Balearic Islands with the exception of the island of Menorca. The putschists failed in the provinces of Madrid, Valencia and Barcelona, where 70% of Spanish industry and the majority of the Spanish population were concentrated.

On July 24, the Nationalists of the Northern Army under General Mola proclaimed a counter-government in Burgos, the Junta de Defensa Nacional, presided over by General Miguel Cabanellas. They deliberately left open the question of the form of government they sought in order to keep the groups supporting them (Falangists, Carlistists, Alfonsists, etc.) on their side. In the south, General Queipo claimed leadership of the Nationalists. Franco was not finally able to assert himself as leader of the Nationalist movement throughout Spain until September 1936, without being forgiven by his rivals.

About half of the regular Spanish army, including 10,000 officers alone, two-thirds of the Carabineros (border police) controlled by Queipo, 40% of the Asaltos and 60% of the Guardia Civil, sided with the nationalists. The insurgents' most important fighting instrument was the Africa Army with its Moorish mercenaries and the Foreign Legion, plus the Carlist militias (Requeté) and the Falange, which retained relatively independent command structures until 1937. The Nationalists received financial and logistical support from Italy and the German Reich at the beginning of the Civil War.

Loyal to the Republic remained the majority of the generals, two-thirds of the navy and half of the air force, but they could not compensate for the absence of an intact officer and non-commissioned officer corps in the crucial first months. The troops that remained loyal, with the paramilitary Guardia Civil and the Guardia de Asalto, along with militia groups of the Social Democrats, the Communists, the Socialists, and the anarcho-syndicalists, formed the military backbone of the Republic at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. The Republic also received substantial support from international volunteers.

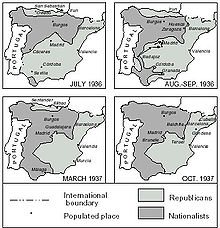

Territories under control ! of the government and ! the putschistsEnd of July 1936

War History

See also: Chronology of the Spanish Civil War

1936

The last hopes of a quick end were dashed on July 21, the fifth day of the uprising, when the Nationalists captured the Ferrol naval base in northwestern Spain, where they seized two factory-built cruisers. Furthermore, Franco's first airlift in history helped move troops from the Spanish colonies to the mainland, bypassing the Republican naval blockade in the Straits of Gibraltar and consolidating the territory they controlled. This encouraged the fascist countries of Europe to support Franco, who had already made contact with the Nazi state and Italy the day before. On July 26, the Axis powers decided to assist the Nationalists; aid began in early August. The Axis powers provided financial aid to Franco from the beginning.

Despite the government's countermeasures, by early August the coup plotters had succeeded in putting parts of the Afrikaans Army (initially about 12,000 men) across the Strait of Gibraltar. Under Colonel Yagüe, the main force moved north to secure the area along the Portuguese border. This included the battles of Mérida and Badajoz. As a result, the victors carried out mass executions of the Republican defenders. Following this, Yagüe's troops turned east to march on Madrid. After several engagements, including the Battle of Sierra Guadalupe and the Battle of Talavera, they were still 100 kilometers from Madrid by early September. At this point Franco personally intervened in the operations: he ordered Yagüe to swing off to Toledo, where the siege of the Alcázar of Toledo by Republicans had been taking place since July. Although the Nationalists won an important propaganda victory by capturing Toledo on 27 September and ending the siege of the Alcázar, they thereby squandered the chance of an early capture of the capital. Two days later Franco declared himself Generalísimo (Generalissimo) and Caudillo (Leader).

In the northeast, the nationalist offensive of Guipúzcoa had begun in August to cut off the Basque Country from the French border. The rebels benefited from the fact that the French government had closed the border in August. The Republican coastal strip in northern Spain was completely isolated by the Nationalists' successes by the end of September. Mola's northern army also made independent advances on Madrid, but all of them got bogged down in the mountain ranges north of Madrid.

In the Balearic Islands, Republican troops from Barcelona attempted to land from Menorca in August. While Ibiza and Formentera were occupied with little resistance, the attack on Mallorca in early September failed despite numerical superiority and air and sea support. Menorca remained in Republican possession until shortly before the end of the war, while the rest of the Balearic Islands were definitively occupied by nationalists and Mallorca served as a base for Italian bombers for attacks on Catalonia until the end of the war.

The Nationalists began a new major offensive from the west towards Madrid in October, with a force ratio of 1:3. Increasing government resistance, popular mobilization and the intervention of reinforcements (including the XI and XII International Brigades and the anarchist Durruti Column) brought the advance to a halt on November 8. International Brigade and the anarchist Durruti Column) brought the advance to a halt on November 8. Meanwhile, on November 6, the government had withdrawn from Madrid, out of the combat zone, to Valencia. In Paracuellos de Jarama and Torrejón de Ardoz, mass shootings of Franco supporters and Catholics were carried out by the Republicans. The Battle of Madrid 1936, which lasted until December, resulted in a siege that lasted until shortly before the end of the war.

The Axis powers officially recognised the Franco regime after the liberation of the Nationalist Spanish soldiers trapped in the fortress of Toledo on 18 November, and on 23 December Italy sent its own volunteers to fight for the Nationalists.

1937

With forces reinforced by Italian troops and colonial troops from Morocco, Franco tried again to conquer Madrid in January and February 1937, but again failed in several battles for the road to Coruña. In one of the first actions of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (CTV), the coastal strip around Málaga was captured on 8 February in the Battle of Málaga. This resulted in the Massacre of Málaga, when Nationalist air and naval units fired on fleeing residents of Málaga.

Franco planned a large-scale two-pronged encirclement operation against Madrid in February, but it was only partially executed due to delays in the deployment of the CTV. In the Battle of Jarama, southeast of Madrid, which lasted until the end of February, the Republicans held their ground despite heavy losses. When the Italians finally attacked to the north of Madrid the following month, they suffered a heavy defeat at the Battle of Guadalajara. In these battles, the Republicans used the advantage of the interior lines, which allowed them to move troops quickly to threatened sections of the front.

Franco realised that the war could not be ended in this way and shifted the focus of his warfare to the isolated, still Republican, coastal provinces in the north, beginning the "War in the North" which lasted six months. The first to be attacked, starting on 31 March, was Bizkaia in the Basque Country, with the Condor Legion flying heavy air attacks on Republican positions and towns in the hinterland. Two of these attacks, on Durango and Guernica, are remembered for their indiscriminate bombing of civilians with high casualty rates. They also had considerable repercussions on international public opinion of the war. Franco's troops entered Guernica on April 28, two days after its destruction by the Condor Legion. Thereafter, however, the government began to fight back with increasing efficiency.

In early May, intra-Republican clashes broke out in Barcelona between the now Communist-dominated Catalan regional government and the anarchists of the CNT/FAI and POUM, which subsequently weakened the Republican side significantly. Head of government Caballero, who had resisted the Communist capture of the army and government, resigned under Communist pressure a week after the events. He was succeeded by the Socialist Juan Negrín, but the real power behind the government increasingly became the Communists.

In May and June, the government launched two offensives on the central front at Segovia and Huesca to force Franco to withdraw troops from the northern front and thus halt their advance on Bilbao. Both failed after initial successes. Mola, Franco's deputy commander on the northern front, was killed in a plane crash on June 3, and was succeeded by Fidel Dávila. On June 19, Bilbao was captured after the Basque army withdrew.

In early July, the government even launched a strong counter-offensive at Brunete, in the Madrid area, to relieve the capital as well as the northern front. However, the Nationalists were able to repel this with some difficulty and using the Condor Legion. Likewise, an offensive launched at the end of August to take Saragossa failed in the Battle of Belchite.

Franco was then able to regain the initiative. His troops were able to advance into Cantabria and Asturias and by the end of October had captured the cities of Santander and Gijón, which meant the elimination of the northern front. Industries and coal mines vital to the war effort fell into the hands of the Nationalists. On August 28, the Holy See recognized Franco, under pressure from Mussolini. At the end of November, as the Nationalists came perilously close to Valencia, the government went to Barcelona.

1938

In January and February, the two parties fought for possession of the city of Teruel, with the Nationalists finally holding it from 22 February. On 6 March, the Republican side won the largest naval engagement of the entire Civil War, sinking the heavy cruiser Baleares in the Battle of Cabo de Palos. The outcome of the engagement had no bearing on the course of the war. On April 14, the Nationalists broke through to the Mediterranean. The Republican territory was thus divided in two. In May the government asked for peace, but Franco demanded unconditional surrender, and so the war continued. The government now began a major offensive to reconnect their territories: The Battle of the Ebro began on July 24 and lasted until November 26. The offensive was a failure and determined the final outcome of the war. Eight days before the end of the year, Franco struck back by mustering strong forces for an invasion of Catalonia.

1939

The Nationalist offensive, which began on 23 December 1938, led to the occupation of Catalonia within a few weeks. Tarragona fell on 15 January, Barcelona on 26 January and Girona on 4 February. By February 10, all of Catalonia was occupied. By then, in anticipation of a massacre, some 450,000 people had tried to escape to France despite cold, snow, and constant attacks from the air. The French government opened the border on January 28 to civilians and on February 5 to members of the Republican forces, who were interned in improvised camps such as Camp de Gurs. President Azaña and Prime Minister Negrín crossed the border on February 6 and 9, respectively. While Negrín immediately returned to the Republican zone, Azaña resigned as President of the Republic in France at the end of February.

After the loss of Catalonia, the Republic controlled only a third of Spanish territory, but its armed forces were still about 500,000 strong. Negrín, however, who was now supported only by the Communists and part of the Socialist Party, wanted to continue the war until the beginning of a war between the major European powers, which he expected. However, the plan to "integrate" the Spanish Civil War into a European war and thus still win was thwarted by the governments of Great Britain and France as early as February 27, when they diplomatically recognized Franco's government.

On March 4-5, 1939, parts of the Republican Army under Colonel Segismundo Casado putsched against the Negrín government in Madrid under the pretext that a Communist takeover was imminent. They were supported by anti-communist anarchists around Cipriano Mera and Eduardo Val and by representatives of the right wing of the PSOE around Julián Besteiro. Both Casado and Besteiro were in contact with representatives of Franco's "fifth column," who had given them to understand that a negotiated surrender was possible and that only the Communists would be persecuted if Madrid were surrendered without a fight. In a "civil war within a civil war" that lasted several days and cost the lives of some 2,000 people, the Consejo Nacional de Defensa they had formed prevailed over the I Corps commanded by Communist officers. Its commander was executed, numerous communists were imprisoned, left in jail when Franco's troops invaded, and then immediately killed by them. A similar revolt in the naval base of Cartagena, in which the "fifth column" openly participated, was once again put down by Republican troops. However, the fleet retreated to French North Africa, making Negrín's planned mass evacuation impossible.

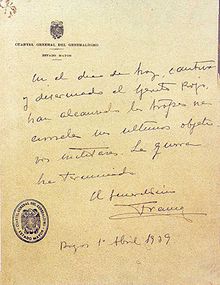

After the Casado coup, the Republican resistance collapsed. All along the front, soldiers went into captivity or deserted. Some smaller units went underground to organize a guerrilla war that lasted in some areas until 1951. Despite the de facto disbandment of the Republican army, Franco did not order the general advance of "national" troops until March 26. Without yet encountering organized resistance, they occupied all the remaining territory of the Republic within a few days. Madrid fell on March 27. On March 30, Italian troops occupied Alicante, where tens of thousands of refugees had hoped in vain to evacuate. Negrín escaped and formed a government-in-exile in France; Casado and some of his supporters were picked up by a British destroyer in Gandía after agreements with Franco and the British government. A bulletin from Franco declared the civil war over on April 1, 1939.

Franco's bulletin, which announced the defeat of the "red army" and the end of the Civil War on April 1, 1939.

Guernica destroyed by the German Condor Legion

Four stages of the front from July 1936 to October 1937

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Spanish Civil War?

A: The Spanish Civil War was a civil war between Republicans and Nationalists that took place from 18 July 1936 to 1 April 1939.

Q: Who were the two sides in the Spanish Civil War?

A: The two sides in the Spanish Civil War were Republicans and Nationalists.

Q: When did the Spanish Civil War end?

A: The Spanish Civil War ended on 1 April 1939, when the last Republican troops surrendered.

Q: Who became dictator of Spain after the war?

A: After the war, Francisco Franco became dictator of Spain until he died in 1975.

Q: How long did Franco remain dictator of Spain?

A: Franco remained dictator of Spain for 36 years, until his death in 1975.

Q: What happened on 18 July 1936?

A: On 18 July 1936, the Spanish Civil War began with a conflict between Republicans and Nationalists.

Q: What caused the end of the Spanish Civil War? A: The end of the Spanish Civil War was caused by when last Republican troops surrendered on 1 April 1939.

Search within the encyclopedia