Soviet invasion of Poland

Soviet occupation of eastern Poland

Part of: World War II

Red Army parade in Lviv (Lwów/Lemberg), 1939

The Soviet occupation of eastern Poland, the Kresy, began with the invasion of the RedArmy on September 17, 1939, after German troops invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and surrounded the main Polish forces near Kutno. The last regular Polish units surrendered on October 6, 1939. The occupation period was marked by the transformation of society along Soviet lines and accompanied by terror, mass shootings, and deportations.

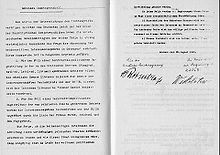

In the secret additional protocol to the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 23 August 1939, a demarcation line had been agreed that separated the respective areas of interest. In the German-Soviet Border and Friendship Treaty of September 28, 1939, the demarcation line was modified somewhat in order to achieve a clearer ethnic division of the territories. Great Britain and France had given a guarantee for the independence of Poland, but did not intervene.

Josef Stalin declared that the invasion of Soviet troops was to protect the Ukrainians and Belarusians living there from the German invasion. The Soviet Union gained an area of 200,000 km². It comprised 52.1 percent of the entire Polish state. Ukrainians and Belarusians were larger ethnic groups living there, while Poles, Jews and Lithuanians were smaller. Russians, Tatars, Armenians, Germans, Czechs and others also lived there. In total, there were 13.2 million people.

During the occupation, parts of the occupied territory were incorporated into the Byelorussian and Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republics. From 1939 to 1941, large landholdings were expropriated, agriculture was collectivized, and land was distributed to peasants. Industry, commerce, and banks were nationalized, the currency was changed to rubles, and the Soviet legal and economic system was introduced. Thus the occupation also became a social upheaval.

Due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Kresy became a war zone again from June 1941.

Previous story

Poland's foreign policy after 1918

In the course of the First World War, the Russian and Austro-Hungarian monarchies fell. The new states in the east and southeast of Europe tried to exploit the resulting power vacuum for their respective interests and new formations. The restored Polish state did not accept the eastern border, which had been provisionally established by the Supreme Council of the Allied Powers (Britain, France, Italy) in a declaration on December 8, 1919, while the Treaty of Versailles had left it undefined. It later became commonly known as the Curzon Line.

Poland took advantage of the weakness of Soviet Russia, which was tied up in the Russian Civil War, and reconquered territories in the east that had been under Polish rule until 1795 during the times of Poland-Lithuania. The Polish-Soviet War developed. In the 1921 Peace of Riga, Soviet Russia relinquished what are now western Ukraine and western Belarus. They became part of the Polish territory as the "Eastern Frontier Marches" (Kresy Wschodnie). The Polish population there constituted only a minority. The next year, on March 24, 1922, Poland annexed the occupied territory around the present-day Lithuanian capital Vilnius, which had supposedly led a sovereign state existence as Central Lithuania.

On 19 February 1921 Poland concluded a defensive alliance with France: in the event of aggression by the German Reich against one of the two partners, the consequence would have been a war on two fronts. However, this defensive alliance was softened by the 1925 Locarno Treaties, when France and Germany guaranteed each other's borders, from which Poland remained excluded. Now Poland was in danger of being caught between the fronts in the event of a German-Soviet understanding. Therefore, on February 9, 1929, it concluded the Litvinov Protocol, in which Poland, the Soviet Union, Romania, Latvia, and Estonia brought the Briand-Kellogg Pact into force ahead of schedule, thus contractually renouncing the use of military force to resolve international disputes. This was followed on 23 January 1932 by the Polish-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, in whose supplementary provision of June 1932 the Soviet Union undertook not to enter into any alliances with Germany directed against Poland. In 1934, Poland signed another non-aggression pact, this time with the now National Socialist German Reich.

Initiation of the non-aggression pact

→ Main article: German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact

With the breakup of Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939, it became clear that Adolf Hitler was not willing to abide by agreements under international law. Britain therefore issued a declaration of guarantee for Poland's independence on 31 March 1939 (Poland had, however, benefited from the weakening of Czechoslovakia at the Munich Agreement in 1938 and annexed the Olsa region). France joined in on April 6. In a secret additional protocol it was agreed that this guarantee applied only in the event of a German attack. However, in order to be able to intervene effectively militarily if necessary, the Western powers needed the cooperation of the Soviet Union for geographical and armament-strategic reasons. Negotiations in Leningrad dragged on, mainly because Poland refused to grant the Red Army rights of passage in separate consultations with a British military delegation in May 1939. Although the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union had been reaffirmed on 26 November 1938, mistrust of the eastern neighbour remained strong: once Soviet troops were in the country, the temptation would be great to use this to regain the territories lost in the 1921 Riga Peace Treaty. British-French-Soviet negotiations were broken off when it was announced on 25 August that the Soviet Union had concluded a non-aggression pact with Germany. The two countries had been probing for some time, in the course of economic negotiations, the confirmation of the German-Soviet neutrality pact of 1926 or the conclusion of a new non-aggression pact. Hitler and Stalin decided in a secret additional protocol to divide northeastern and southeastern Europe into spheres of interest. By agreeing to a secret additional protocol, the Soviet Union accepted a "bougoise" secret diplomacy that violated the openness of international legal agreements as defined by Lenin's Decree on Peace. What prompted Stalin to accommodate German insistence with the secret protocol is subject to differing interpretations. Britain and Poland concluded a military mutual assistance pact. On August 26, 1939, Prime Minister Édouard Daladier also reaffirmed French mutual assistance obligations to Poland.

The Soviet decision to invade...

The German invasion of Poland had begun on September 1, 1939. After France and the United Kingdom had declared war on the German Reich on September 3, the German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop asked the Soviet government on the same day to occupy eastern Poland so that German troops could soon be moved to the denuded western border. Soviet troops were to occupy the area of interest promised to it in the secret protocol. The German government repeatedly urged the Soviet Union to intervene. Stalin and Molotov still hesitated with the occupation of eastern Poland until September 17, in order not to share the role of aggressor with Hitler, but to appear in the historical propaganda as a "peace power" and to be able to wait for the reactions of France and Great Britain, which had issued a declaration of guarantee for the territorial integrity of Poland. Although Britain and France declared war on Germany on September 3, they responded only with a sit-down war. Stalin concluded that the Soviet invasion of Poland would not lead to war with the Western powers. Molotov told the German ambassador Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg on several occasions that in order to "politically underpin" the approach, it was important for the Soviet Union not to strike until the political centre of Poland, the capital Warsaw, had fallen. Molotov therefore urged Schulenburg to "communicate as approximately as possible when Warsaw could be expected to be taken." According to Claudia Weber, the Soviet Union never tired of exerting a little diplomatic pressure on the German Reich to take Warsaw quickly. As a result, the German government angrily let rumors of an armistice with Poland spread. Stalin took this as an opportunity to speed up preparations for the invasion of eastern Poland so as not to go away empty-handed. On September 15, 1939, Vyacheslav Molotov and Tōgō Shigenori signed an armistice agreement ending the Japan-Soviet border conflict, which was an important prerequisite for Stalin to wage war in the West. The invasion occurred shortly after the armistice was signed and before Warsaw surrendered. Out of consideration for public opinion at home and abroad, it was to be justified at first by the "protection of the White Russian and Ukrainian population from the German conquerors". After a protest against it by the German ambassador, it was generally justified on the grounds that the Red Army thus had to protect the "East Slav brother peoples", since all state order in Poland had ceased to exist as a result of the war (debellation). For the Soviet Union, there was a danger that a puppet state of the National Socialists under the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which supported the Wehrmacht against Poland, might emerge on its border. On the night of September 17, Foreign Minister Molotov denounced all treaties to Wacław Grzybowski, the Polish ambassador in Moscow, saying that the Polish state had ceased to exist. Molotov stated publicly later the same day that the Soviet Union had hitherto pursued a policy of neutrality, which was now no longer possible in view of the changed situation vis-à-vis Poland. However, the Soviet Union wanted to remain neutral towards all other states.

What overriding goals the Soviet Union pursued with the conclusion of the non-aggression pact and the subsequent invasion of Poland is still disputed in research today. Dmitri Volkogonov, on the other hand, in his biography of Stalin, took the view that the decision to protect the population of the occupied territories "from the threat of German invasion [...] corresponded to the interests of the working people of these territories" and was thus justified. Russian historians also argue that the Soviet troops were received everywhere as liberators in 1939. Thus Mikhail Meltyukhov agrees with Mikhail Semiryaga, who wrote that "the results of the elections [in Soviet-occupied Poland in 1939] showed that the overwhelming majority of the population of these regions had agreed to the introduction of Soviet power and unification with the Soviet Union."

Ingeborg Fleischhauer interprets the Soviet action as the result of a rather defensive realpolitik, to which Stalin had hardly had a realistic alternative in view of the isolation into which his country had fallen since the Munich Agreement of 1938. Without the invasion, a vacuum would have been created in eastern Poland "which could dangerously quickly become a pull for the German Wehrmacht." Nor could the assertion that chaos was imminent and that the Eastern Slav population had to be protected be dismissed as pure propaganda. Bianka Pietrow-Ennker sees behind the Soviet invasion, on the one hand, the efforts of the Soviet leadership to secure the Soviet border, and on the other hand, the interest in territorial changes, which were propagated as strengthening the Soviet Union and continuing the world revolution. The perspective of a military conflict with Germany had played no role. Stalin seems to have assumed an Allied victory over Germany and to have wanted to secure a good negotiating position for the demarcation of the border in Eastern Europe vis-à-vis a future negotiating partner, Great Britain.

Sergei Slutsch interprets the invasion as an offensive act. Contrary to what Molotov claimed, the Soviet Union had not remained neutral since September 1, 1939, but had actively supported a warring party, namely Germany. The annulment of the non-aggression pact with Poland should therefore have taken place, as a matter of law, on September 1. From ignorance of the current whereabouts of the Polish Government one should not conclude that it no longer existed. In fact, the Government of Prime Minister Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski left Poland only on 18 September, i.e. after the Soviet invasion. Moreover, the cessation of a government's political activity by no means necessarily entailed the dissolution of the state. Stalin's annexation policy had to be seen as part of the Second World War, which for the Soviet Union did not begin with the German invasion on 22 June 1941. According to Norman Davies, the invasion of the Red Army, which began on 17 September, was the decisive blow that sealed Poland's defeat: "Poland was heinously murdered by two invaders acting in collusion".

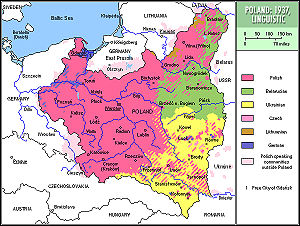

Poland, language map 1937 in a Polish representation from 1928

Curzon Line and Polish Land Gains through War and Treaties 1919-1922

Military operations

Soviet attack preparations

In late August 1939, Red Army Chief of Staff General Boris Shaposhnikov began to draw up a Soviet plan of attack. On August 30, after the Polish general mobilization, the Soviet news agency TASS announced the plan to significantly strengthen the numerical strength of the garrisons on the western borders of the USSR. After the Wehrmacht attack on September 1, 1939, Soviet forces began to make practical preparations for the invasion. On September 3, People's Commissar Kliment Voroshilov ordered troops in Belarus and Ukraine to be on combat readiness. On September 6, general mobilization was declared in the Soviet Union; from September 8 to 13, Soviet troops were then moved to the border and grouped into two main assault groups (fronts).

| Army/Front | Soldiers | Artillery | Tank |

| White Russian Front, Army General Mikhail Prokofievich Kovalev | 378.610 | 3.167 | 2.406 |

| General Vasily Ivanovich Kuznetsov, 3rd Army. | 121.968 | 752 | 743 |

| Mechanized Cavalry Group, General Ivan Vassilyevich Boldin | 65.595 | 1.234 | 834 |

| 10th Army, General Ivan Grigorievich Sakharakin | 42.135 | 330 | 28 |

| 4th Army, General Vassily Ivanovich Chuikov. | 40.365 | 184 | 508 |

| Independent 23rd Rifle Corps | 18.547 | 147 | 28 |

| Reserve: 11th Army, General Nikifor Vasilyevich Medvedev | 90.000* | 520* | 265 |

| Ukrainian Front, Army General Semyon Konstantinovich Tymoshenko | 238.978 | 1.792 | 2.330 |

| Fifth Army, General Ivan Gerasimovich Sovetnikov. | 80.844 | 635 | 522 |

| 6th Army, General Filipp Ivanovich Golikov | 80.834 | 630 | 675 |

| General Ivan Vladimirovich Tyulenev, 12th Army. | 77.300 | 527 | 1.133 |

| All together | 617.588 | 4.959 | 4.736 |

*) estimated figures

Military occupation by the Red Army

On September 17, Soviet troops crossed the Polish eastern border.

Red Army troops were divided into two fronts, with 25 rifle divisions, 16 cavalry divisions, and 12 tank brigades. The total strength was 466,516 men, 3,739 tanks, 380 armored cars and about 2,000 combat aircraft.

- Main directions of attack of the White Russian Front:

Vilnius - Baranowicze - Wołkowysk - Grodno - Suwałki - Brest-Litovsk, reaching Vilnius, Grodno and Brest between September 20 and 22, and Suwałki on September 24.

- Main directions of attack of the Ukrainian Front:

Dubno - Łuck - Vladimir Wolinsk - Chełm - Zamość - Lublin, Tarnopol - Lviv - Czortków - Stanislau - Stryj - Sambor and Kolomea.

The Red Army reached Lviv on September 19, Lublin on September 28. In total, the units of the Ukrainian Front were involved in various combat operations until the beginning of October.

On September 22, 1939, General of the Tank Troops Heinz Guderian and brigade commander Semyon Kriwoschein took the first joint German-Soviet military parade in Poland, solemnly exchanged swastika for Red Flag, wounded scattered soldiers of the Wehrmacht, cared for by Soviet doctors, were handed over. During the parade at the demarcation line in the town of Brest-Litovsk, which was divided between the two allied aggressors, Kriwoschein, on behalf of the Soviet leadership, congratulated the Germans on their war successes and declared his intention to welcome the Germans to Moscow after their forthcoming victory over Great Britain.

The high speed of the Soviet advances had several reasons: One was the wartime successes of the Wehrmacht in western Poland, but also the fact that the Soviet attack came as a complete surprise and thus the Polish Army was neither properly positioned to repel an attack from the east, nor did it have clear combat orders against the Red Army. Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły issued only one order on September 17, 1939:

"[...] general retreat to Romania and Hungary. [...] Do not fight with Bolsheviks unless in an attempt to disarm or an attack on their part."

In addition, there were also purely military reasons: Both aggressors were far superior to Polish troops both in terms of numbers and in terms of their equipment with modern weapons such as tanks and fighter planes. The Polish army was simply not up to a two-front war.

Polish prisoners of war of the Red Army (September 1939)

Victory parade, Heinz Guderian and Semjon Kriwoschein in Brest-Litowsk, 22 September 1939

Europe after September 28, 1939

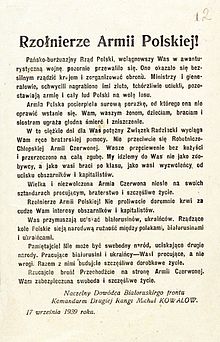

Soviet appeal to Polish soldiers of September 17, 1939, blaming the war on the Polish government

Secret Additional Protocol to the Hitler-Stalin Pact

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland?

A: The 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland was a Soviet military operation that started without a formal declaration of war on 17 September, 1939. It was during the early stages of World War II, after Nazi Germany had invaded Poland from the west on September 1.

Q: When did the Soviet Union invade?

A: The Soviet Union invaded from the east and ended on 6 October 1939.

Q: What happened to the Second Polish Republic?

A: Germany and the Soviet Union divided the whole of the Second Polish Republic.

Q: What did the Soviets ask other countries to do in early 1939?

A: In early 1939, the Soviet Union asked the United Kingdom, France, Poland, and Romania to make an alliance against Nazi Germany. They also wanted Poland and Romania to let them pass through their territories but they refused.

Q: How did Nazi Germany respond?

A: Nazi Germany responded by invading Poland from three directions one week later.

Q: How did people in eastern Poland become citizens of Russia?

A: The Soviets took over this area and made all 13.5 million formerly-Polish citizens become citizens of Russia in November 1939. They also sent hundreds of thousands of people from this region to Siberia or other remote parts of Russia as well.

Q: When were these areas under Nazi occupation until?

A: These areas were under Nazi occupation until they were reconquered by Red Army in summer 1944.

Q:What agreement at Yalta Conference allowed for keeping almost all occupied territory by USSR ?

A:The agreement at Yalta Conference allowed for keeping almost all occupied territory by USSR , which included southern half East Prussia and lands east Oder-Neisse Line . These areas were then put into Ukrainian & Byelorussian Socialist Republics .

Search within the encyclopedia