Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

![]()

Grundgesetz is a redirect to this article. For other basic laws, see the list of basic laws.

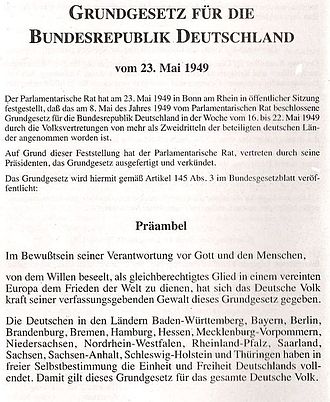

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany of 23 May 1949 (short German Basic Law; generally abbreviated GG, more rarely also GrundG) is the constitution of Germany.

The Parliamentary Council, which met in Bonn from September 1948 to June 1949, drafted and approved the Basic Law on behalf of the three Western occupying powers. It was adopted by all German state parliaments in the three western zones with the exception of Bavaria. There was therefore no referendum. This, and the fact that it was not called a "constitution", was intended to emphasise the provisional nature of the Basic Law and the Federal Republic of Germany that it established. The Parliamentary Council was of the opinion that the German Reich continued to exist and that a new constitution for the entire state could therefore only be adopted by all Germans or their elected representatives. However, because the Germans in the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ) and the Saarland were prevented from participating, a "Basic Law" was to be created for a transitional period as a "provisional partial constitution of West Germany": The original preamble emphasized the will of the German people for national and state unity. The Saarland became part of the Federal Republic on 1 January 1957 and thus came within the scope of the Basic Law. With the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990, it became the constitution of the entire German people (→ Preamble).

The Basic Law fulfils the criteria of a substantive constitutional concept from the outset by making a basic decision on the form of the country's political existence: democracy, republic, welfare state, federal state and essential principles of the rule of law. In addition to these basic decisions, it regulates the organisation of the state, secures individual freedoms and establishes an objective order of values.

The fundamental rights enshrined in the Basic Law are of particular importance due to the experiences of the National Socialist unjust state. They bind all state authority as directly applicable law (Article 1.3). By their constitutive establishment, the fundamental rights are therefore not merely provisions on state objectives; rather, as a rule, no judicial authority is required to exercise them, and legislation, executive power and jurisdiction are bound by them. From this derives the principle that fundamental rights are to be understood primarily as defensive rights of the citizen against the state, while they also embody an objective order of values which applies as a basic constitutional decision to all areas of law. The social and political structure of the state-constituted society is thus determined by constitutional law.

The Federal Constitutional Court, as an independent constitutional body, preserves the function of the fundamental rights, the political and state organizational system and develops them further. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany in its present form establishes a perpetuated and legitimized state constitution. It can only be replaced by the people by adopting a new constitution (Art. 146).

The first 19 articles of the Basic Law, the Basic Rights (original version), at the Jakob-Kaiser-Haus in Berlin

Preamble of the Basic Law as amended by the Unification Treaty (1990)

Etymology

The German word Grundgesetz first appeared in the 17th century and is considered by linguists to be a loan translation or Germanization of the term lex fundamentalis, which was coined in Latin legal terminology; "Grundgesetz" therefore means the "[state's] fundamental law".

All other laws that do not have constitutional status are also referred to as simple laws.

Genesis

Between the end of the war and the London Six-Power Conference

Even before the London Conference of the Six Powers, the Allies called on the politically active Germans in the occupation zones to think about a new state structure for Germany. On 12 June 1947, for example, the British military governor, Sir Brian Robertson, called on the Zonal Advisory Council set up in his occupation zone to give its opinion on the structure of a post-war German state. While in this zone of occupation the SPD's intention of creating a strong central authority still seemed relatively promising, in southern Germany, with its strong federalist traditions in Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden, the view prevailed that, after the National Socialist unitary state, it would be preferable to reintroduce Germany's traditional division into Länder with statehood and autonomy. The term "Federal Republic of Germany" was first used by the French occupation authorities in Württemberg-Hohenzollern in May 1947.

While the state representatives were able to participate relatively strongly in the constitutional discourse, the leaderships of the parties remained largely without influence, especially since they had not yet been able to constitute themselves on a Germany-wide basis and were thus ruled out as state-wide interest groups. Nevertheless, as early as 1947 and 1948, a clear difference emerged between the CDU/CSU, which in April 1948 presented its "Principles for a German Federal Constitution" with a strongly federalist character, and the SPD, which as early as 1947 condemned any separatism with its Nuremberg Guidelines and wanted to preserve the "unity of the Reich" at all costs.

London Six-Power Conference

→ Main article: London Six-Power Conference

The conference held in London in February and March and from April to June 1948 between the three Western occupying powers, France, the United Kingdom and the United States of America, and three of Germany's direct neighbours, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, dealt intensively with the political reorganisation of the occupied territories in West Germany. Because of the onset of the Cold War, the victorious powers met for the first time without the Soviet Union.

The three occupying powers initially pursued quite different interests: While the centrally organized United Kingdom had no preferences regarding the question of "central state or federalism?" but rather had in mind the unification of the Trizone with the Soviet-occupied zone as smoothly as possible, the United States advocated a German federal state consisting only of the Trizone. For the French, on the other hand, the main objective was to weaken any German state as much as possible: accordingly, they advocated as long a period of occupation as possible without the establishment of a state and the inclusion of the Saarland in the French federation. However, since they were unable to prevail with their position of preventing the founding of a state, the French advocated a federal state structure with international control of the coal and steel industry.

Finally, the final communiqué of the conference included a call to the Germans in the Western Länder to build a federal state. However, this federal West German state was not to be an obstacle to a later agreement with the Soviet Union on the German question.

France's confirmation of this decision came only after massive pressure from the other two Allies and an extremely close vote (297:289) in the National Assembly.

Frankfurt Documents

→ Main article: Frankfurt documents

After the London resolutions had been received rather negatively in Germany, the Frankfurt documents presented to the prime ministers on July 1, 1948, were intended to be more friendly to Germany. In addition to announcing a statute of occupation, the most important of the three documents, Document No. I, contained an authorization to the prime ministers to convene an assembly to draw up a democratic constitution with a guarantee of fundamental rights and with a federal structure. This was then to be approved by the military governors. In doing so, the military governors wanted to avoid the impression of dictating constitutional principles to the Germans; they also refrained from setting a deadline for the prime ministers to respond to the documents. Only the latest date for the convening of the Constituent Assembly was set: September 1, 1948.

Document No. II called upon the prime ministers to review the national boundaries and, depending on the result, to make proposals for their modification; Document No. III contained the points on which the military governors wished to continue to determine. They were to be incorporated into a statute of occupation which was to be put into effect at the same time as the constitutional law.

Coblenz Decisions

→ Main article: Koblenz resolutions

The days following the handover of the Frankfurt documents were marked by great bustle in the state governments and state parliaments. From July 8 to July 10, 1948, the West German heads of government met at the Rittersturz in Koblenz in the French occupation zone. The invitation of the East German prime ministers had not even been considered. In their "Koblenz resolutions" the prime ministers declared their acceptance of the Frankfurt documents. At the same time, however, they opposed the creation of a West German state, since this would cement the division of Germany. The occupation statute was also rejected in its proposed form.

The military governors reacted angrily to the Koblenz resolutions because, in their opinion, they presumptuously attempted to override the London and Frankfurt documents. In the process, the French military governor Marie-Pierre Kœnig had secretly encouraged German politicians to object. In particular, the US military governor Lucius D. Clay blamed the prime ministers for the fact that the French would now again demand a revision of the London decisions that would be disadvantageous to the Germans. At another meeting on July 20, 1948, the negative consequences of insisting on the Koblenz resolutions were made clear to the prime ministers. Although a constitution and not a provisional Basic Law was to be drawn up, the Minister Presidents finally agreed to the demands of the military governors.

At a conference of minister-presidents at Niederwald Castle, the heads of the Länder, despite their acceptance of the London resolutions, adhered to the Koblenz resolutions as a recommendation and to the designation "Basic Law" in order to emphasise its provisional character. Furthermore, it was decided not to have a "constituent assembly" but a Parliamentary Council, elected by the (West) German Landtage, and to have the Basic Law ratified by the Landtage and not - as the military governors wanted - by referendum. The reason for this was that German sovereignty had not yet been sufficiently restored and the conditions for an all-German constitution had not yet been met. The military governors accepted this.

Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee

→ Main article: Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee

The Constitutional Convention at Herrenchiemsee took place from 10 to 23 August 1948. It was to consist more of administrative officials than of politicians. Party-political considerations were to be left completely out of the equation. However, the state parliaments of the American and French occupation zones did not adhere to these recommendations. Although it was not clear whether the members of the Convention were to provide a complete draft of a Basic Law or only an outline, important points crystallized in the discussion, some of which were eventually realized in the Basic Law. These included a strong federal government, the introduction of a neutral and, compared to the Weimar Constitution, substantially disempowered head of state, the extensive exclusion of referendums, and a preliminary form of the later perpetuity clause. The design of the representation of the Länder was already controversial; it was to remain so throughout the deliberations of the Parliamentary Council.

The Convention's groundbreaking preparatory work had a considerable influence on the Parliamentary Council's draft of the Basic Law. At the same time, the Herrenchiemsee Convention was the last major opportunity for the minister-presidents to influence the Basic Law.

Parliamentary Council

→ Main article: Parliamentary Council

Work of the Council

On the basis of the principles of a federal and democratic constitutional state developed within two weeks by the Constitutional Convention, the Parliamentary Council worked out the new constitution. The principle of the members of the Parliamentary Council was the so-called "constitution in short form", namely that Bonn was not Weimar and that the constitution was to have a provisional character in terms of time and space. Only a constitution that had also been created and legitimized democratically throughout Germany was to be called a constitution for Germany. Reunification was laid down as a constitutional objective in the preamble to the Basic Law (→ Wiedervereinigungsgebot) and regulated in Article 23 (which has since been repealed). However, the vote on a constitution pursuant to Article 146, which had been considered in the event of reunification, did not take place in view of the "accession of the German DemocraticRepublic to the area of application of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany". In the reasons for not accepting a constitutional complaint (which only marginally concerned this question), the Second Senate of the Federal Constitutional Court stated on 12 October 1993: "Article 146 of the Basic Law also does not establish an individual right that is subject to a constitutional complaint (Article 93.1 No. 4a of the Basic Law)."

The members of this body (65 in total) were often referred to as the "fathers of the Basic Law"; it was only later that the participation of the four "mothers of the Basic Law" Elisabeth Selbert, Friederike Nadig, Helene Wessel and Helene Weber was remembered. In the process, Elisabeth Selbert had pushed through the equal rights of men and women (Article 3 (2)) against fierce opposition.

The members of the Parliamentary Council were elected by the West German state parliaments according to population proportion and the strength of the state parliamentary parties. North Rhine-Westphalia sent 17, Bavaria 13, Lower Saxony nine, Hesse six, the other Länder between five and one member. Of the 65 members, 27 belonged to the CDU or CSU and another 27 to the SPD, the FDP sent five members, the (national conservative and federalist-oriented) Deutsche Partei, the (Catholic) Zentrum and the (communist) KPD two members each. The stalemate between the major parties prevented any of them from putting their stamp on the Basic Law and forced agreement on the essential issues. The respective voting behaviour of the smaller parliamentary groups was also decisive for the content and adoption of individual sections.

Approval and ratification of the Basic Law

After sometimes heated debates about the lessons to be learned from the failure of the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich and the Second World War, the draft Basic Law was adopted on 8 May 1949 by the Parliamentary Council, which had been meeting in Bonn since September 1948, by 53 votes to 12. The votes against came from deputies of the CSU, the German Party, the Centre Party and the KPD. The date chosen was deliberately the anniversary of the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht, which is why Adenauer forced the vote shortly before midnight. On 12 May 1949, the draft was approved by the military governors of the British, French and American occupation zones, but with some reservations. Under Article 144(1), the draft required approval by the popular assemblies in two-thirds of the German Länder in which it was initially to apply. Between 18 and 21 May it was put to the vote in the Länder parliaments. A total of 10 Länder parliaments adopted the Basic Law.

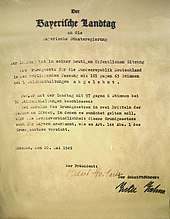

Only the Bavarian Landtag voted against the Basic Law in a session during the night of 19-20 May 1949 by 101 votes to 63, with nine abstentions (seven of the 180 deputies were absent or excused). The proposal for rejection came from the state government. The CSU, which had a majority in the Bavarian state parliament, rejected the Basic Law in contrast to the SPD and FDP. It feared too much federal influence and demanded a stronger federal character, for example equal rights for the Bundesrat in legislation. However, the binding nature of the Basic Law for the Free State of Bavaria in the - eventuality - that two-thirds of the Länder nationwide would ratify the Basic Law, was accepted in a separate resolution by 97 votes out of 180, with 70 abstentions and six votes against.

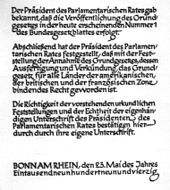

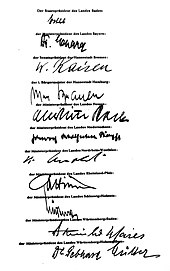

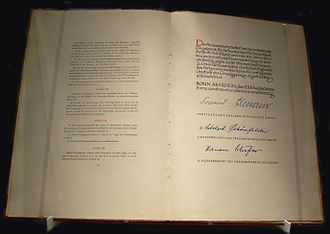

The Basic Law was executed and promulgated by the President and the Vice-Presidents at a formal meeting of the Parliamentary Council on 23 May 1949 (Article 145(1)). The constitutional document was first signed by 63 of the 65 voting members of the Parliamentary Council, i.e., by all but the two dissenting Communist deputies. Then the non-voting West Berlin deputies, the prime ministers and state parliament presidents of the eleven West German states, and finally Otto Suhr and Ernst Reuter as head of the city council and mayor of Greater Berlin, respectively, signed.

"Today, on 23 May 1949, a new chapter in the eventful history of our people begins: today the Federal Republic of Germany will enter into history. Those who have consciously experienced the years since 1933 think with a moved heart that today the new Germany is coming into being."

- Konrad Adenauer (in a speech after the ceremonial signing of the Basic Law)

According to Article 145 (2), it entered into force at the end of that day; the time is sometimes referred to as 23 May, 24:00 hours, sometimes as 24 May, 0:00 hours. The Federal Republic of Germany was thus founded. This event is recorded in the opening formula.

The Basic Law was published in number 1 of the Federal Law Gazette in accordance with Article 145 (3). The original document ("Urschrift des Grundgesetzes") is kept in the Bundestag. The Basic Law also applied in and for Berlin (West), but only insofar as measures of the occupying powers did not restrict its application. Their reservation precluded federal organs from directly exercising state power over Berlin.

On October 3, 2016, the first signed version of the Basic Law with all accompanying files totaling approximately 30,000 pages, including transcripts of the discussions and debates of the Parliamentary Council, the Länder, and also the Allied powers, was stored as microfilm in the Central Salvage Site of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Barbara Tunnel, by the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance.

Proclamation

Publication of the Basic Law on page 1 of the first number of the Federal Law Gazette

Ratification signatures of the Minister Presidents of the German Länder for the adoption of the Basic Law

Rejection by Bavaria

Participants of the Rittersturz Conference from left: Lorenz Bock, Viktor Renner, Franz Suchan, Hermann Lüdemann, Rudolf Katz, Hinrich Wilhelm Kopf, Justus Danckwerts

authentication page

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the name of Germany's constitution?

A: The Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Q: When was it written?

A: It was written in 1949 when Germany was split into East and West Germany.

Q: How does it differ from the Weimar Republic's constitution?

A: Many parts of the Basic Law are very different from the constitution of the Weimar Republic.

Q: Why didn't they call it a "constitution"?

A: The writers decided not to call it a "constitution" because they hoped it would only be a temporary law for West Germany and that the two Germanys would soon be made into one.

Q: How long did it take for East and West Germany to become one country again?

A: It took more than 40 years before East and West Germany became one country again.

Q: Why has the old name been kept?

A: The old name, Basic Law, has been kept even though East and West Germany have become one country again.

Search within the encyclopedia