Soul

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Soul (disambiguation).

The term soul has many meanings, depending on the different mythical, religious, philosophical or psychological traditions and teachings in which it appears. In contemporary usage, it often refers to the totality of all emotional and mental processes in humans. In this sense, "soul" is largely synonymous with "psyche," the Greek word for soul. However, "soul" can also refer to a principle which is assumed to underlie these emotions and processes, to order them and also to bring about or influence physical processes.

In addition, there are religious and philosophical concepts in which "soul" refers to an immaterial principle that is understood as the bearer of an individual's life and his or her constant identity through time. This is often associated with the assumption that the soul is independent of the body, and thus of physical death, in terms of its existence, and is therefore immortal. Death is then interpreted as a process of separation of soul and body. In some traditions it is taught that the soul already exists before conception, that it inhabits and controls the body only temporarily and uses it as a tool or is locked up in it like in a prison. In many such doctrines the immortal soul alone constitutes the person; the corruptible body is regarded as inessential or as a burden and hindrance to the soul. Numerous myths and religious dogmas make statements about the fate that awaits the soul after the death of the body. In a large number of teachings it is assumed that a transmigration of souls (reincarnation) takes place, i.e. that the soul has a home in different bodies one after the other.

In the early modern period, from the 17th century onwards, the traditional concept of the soul, originating in ancient philosophy, as the life principle of all living beings that controls bodily functions, was increasingly rejected, as it was not needed to explain the affects and bodily processes. Influential was the model of René Descartes, who attributed a soul only to humans and limited its function to thinking. Descartes' doctrine was followed by the debate on the "mind-body problem", which continues today and is the subject of philosophy of mind. This concerns the question of the relationship between mental and physical states.

In modern philosophy, a broad spectrum of strongly divergent approaches is discussed. It ranges from positions that assume the existence of an independent, body-independent mental substance to eliminative materialism, according to which all statements about the mental are inappropriate, since nothing in reality corresponds to them; rather, all apparently "mental" states and processes are completely reducible to the biological. Between these radical positions there are different models, which do not deny the reality of the mental, but allow the concept of the soul only conditionally in a more or less weak sense.

An angel and a devil fighting for the soul of a dying bishop. Catalan tempera painting, 15th century

Modern Philosophy, Psychology and Anthropology

From a modern systematic perspective, the philosophical questions related to the topic of the soul can be grouped into different subject areas. These belong for the most part to the fields of epistemology (including theory of perception), philosophy of mind and ontology. Central is the so-called mind-body problem, i.e. the question of how physical and mental phenomena are related. Questions are asked, for example, whether bodily and mental phenomena are based on the same or an ontologically different substance and whether there is a real interaction of reflections and bodily states or whether consciousness is a mere consequential effect of somatic and especially neuronal determinants.

The Cartesian model and its aftermath

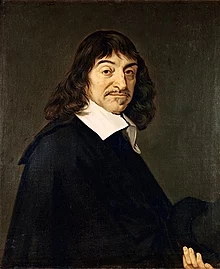

In modern times, the debate was given new impetus in particular by the natural philosophy and metaphysics of René Descartes (1596-1650). His way of thinking is called Cartesian in reference to the Latinized form of the philosopher's name. Descartes rejected the traditional Aristotelian understanding of the soul as a life principle that enables and controls activities of living things such as nutrition, movement, and sense perception, as well as being responsible for the affects. He considered all processes that occur not only in humans but also in animals to be soulless and purely mechanical. Accordingly, animals have no soul, but are machine-like. He identified the soul exclusively with the mind (Latin mens), whose function was only thinking. In Descartes' view, one has to distinguish strictly between matter (res extensa), which is characterized by its spatial extension, and the thinking soul (res cogitans), which has no extension. The thinking subject can only obtain certainty directly from its own thinking activity. Thus it can gain a starting point of knowledge of nature and the world. The body, to whose domain Descartes counts the irrational acts of life, is a part of matter and can be fully explained within the framework of mechanics, whereas the thinking soul, as an immaterial entity, defies such explanation. For Descartes, the soul is a pure, unchanging substance and therefore inherently immortal.

Descartes' central argument for his dualistic position is still discussed with variations in philosophy today. It says that first of all one can clearly imagine that thinking as a mental process takes place independently of the body. Everything that can be clearly and distinctly imagined is at least theoretically possible, it could have been arranged accordingly by God. If it is at least theoretically possible for soul and body to exist independently of each other, then they must be different entities. A second, natural philosophical argument states that the ability to speak and to act intelligently cannot be explained by the interaction of physical components according to natural laws, but rather presupposes something non-physical that can rightly be called soul.

In the context of the seventeenth-century debates about Aristotelian vitalism, which understands the soul as a form, individuation principle, and control organ of the body, and the Cartesian mechanistic interpretation, which seeks to explain all bodily functions by natural laws, Anne Conway (1631-1679) took a special position. She criticized Cartesian dualism, among other things, by arguing that it applied local and other terms to the soul in contradiction to its presuppositions, which, according to dualist understanding, were appropriate only for matter. Moreover, in dualism, the connection between soul and body is not plausible; an interaction of soul and body-such as mental control or the sensation of pain-presupposes that they share common properties. Therefore, Conway assumed only one substance in the universe. In her system, matter and mind are not absolutely distinct, but two manifestations of the one substance; hence they can merge into each other.

The Cambridge Platonists, a group of seventeenth-century English philosophers and theologians with a Neoplatonic orientation, made the defense of the individual immortality of the soul one of their main concerns. In doing so, they opposed both the idea of the individual soul being absorbed into a comprehensive unity and the materialistic concept of the end of personality with death. Against materialism they argued in particular that a sufficient mechanical explanation of life processes and spiritual processes was not possible. Their basic anti-mechanistic attitude also led them to criticize the Cartesians' mechanistic view of nature.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) developed his concept of the soul in opposition to the Cartesian model. Like Descartes, he assumed immaterial souls. Unlike the French philosopher, however, he considered the essential criterion to be not the opposition between thought and extension (matter), but the difference between the ability to have ideas and the absence of this ability. Hence Leibniz rejected the Cartesian thesis that animals were machines, and held that at least some animals had souls, since they possessed memory. He attributed an individual continued existence after death not only to human but also to animal souls.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) considered it impossible to prove or disprove the existence of an immortal soul on a theoretical level. With his opinion he turned against both the traditional metaphysics of the soul based on Platonism and Cartesianism. His argument in the Critique of Pure Reason, however, was not directed against the assumption of an immortal soul. He only disputed its provability and the scientificity of a "rational psychology" which attempts to gain knowledge about the soul by mere deductions from something immediately obvious, self-consciousness, independently of all experience. Rational psychology, he argued, is built solely on the proposition "I think," and this foundation is too tenuous for statements about the substantiality and properties of the soul. Kant submitted that the alleged proofs of immortality were paralogisms (false conclusions). From the fact of self-consciousness, a substantive self-knowledge of the soul could not be gained, as Descartes thought. Within pure rationality, self-knowledge does not go beyond the determination of a self-relation that is empty in content; as soon as one proceeds to statements about states and properties of the soul, however, one cannot do without experience. In its self-perception, the subject could not grasp itself as a thing-in-itself, but only as an appearance, and when it thought about itself, the object of this thought was a pure thought-thing, which the various variants of the traditional metaphysics of the soul confused with a thing-in-itself. From this, however, Kant did not conclude that the concept of soul was superfluous in science. Rather, he considered an empirical psychology that provided a natural description of the soul to be useful; however, this could not lead to an ontological description of essence. Kant also attributed an empirically explorable soul to animals, referring to analogies between humans and animals.

Independently of his criticism of rational psychology, Kant affirmed the assumption that the human soul is immortal on the basis of moral philosophical considerations. According to his reasoning, this is a postulate of practical reason. The soul is not already immortal if it will live and continue after death, but only if it must do so according to its nature. The latter is to be assumed if the moral subject is understood as a being whose will can be determined by moral law. Such a subject necessarily strives for the "highest good," that is, for a perfect morality, which, however, is unattainable in the world of the senses. This requires a progression into the infinite and thus an existence that continues into the infinite. Kant considered the attainability of what a moral being necessarily strives for to be a plausible assumption within the framework of practical reason. Therefore, he pleaded for an "advocacy" of immortality.

The search for the soul organ

The question of the seat of the soul continued to be topical in the early modern period, and questions were also asked about its organ. The soul organ was understood to be the material substrate for the interaction of mind and body, the instrument with which the soul receives impressions from the outside world and transmits commands to the body.

Averroistic-minded scholars of the 15th and 16th centuries were of the opinion that the intellect was not located in a specific place and had no organ of its own, but acted in the entire body. As an impersonal and imperishable entity, it was not bound to bodily functions. This view was opposed by Thomists as well as non-Averroistic Aristotelians and humanists influenced by the thinking of the church father Augustine. For the proponents of a soul organ, the starting point for clarifying the question was the study of the brain ventricles. This approach was followed by Leonardo da Vinci, who argued inductively. He believed that nature does not produce anything inexpedient and that it is therefore possible to deduce from the study of the structures it produces which organic system is assigned to the functions of the soul. Following this principle, Leonardo assigned the reception of sensory data to the first ventricle, the capacity for imagination and judgment to the second ventricle, and the function of memory storage to the third.

According to Descartes' dualistic concept, the inextensible soul cannot be located in the body or in any place in the material world, but there is a communication between soul and body that must take place in a locatable place. Descartes conjectured that the pineal gland, an organ centrally located in the brain, was that place. His assumption was soon refuted by brain research, but the debate about Descartes' theory led to numerous new hypotheses about the location of the soul organ. Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777) assumed that the soul organ was distributed throughout the white matter of the brain.

The last large-scale attempt to localize the soul organ was made by the anatomist Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring in his On the Organ of the Soul, published in 1796. By assigning the brain ventricles a central role in the communication between soul and body, he made the traditional ventricular theory the starting point of his considerations. What was new, however, was his argument. He argued that only in the ventricular fluid could the individual sensory stimuli combine to form a unified phenomenon, and pointed out that the ends of the cranial nerves extend to the ventricular walls. As an organ of the soul he determined the cerebrospinal fluid, which washed around and connected the cranial nerves. Soemmerring, however, did not limit himself to empirical statements, but claimed that the search for the soul organ was the subject of the "most trancendental physiology leading into the realms of metaphysics". He hoped for support from Immanuel Kant, who wrote the epilogue to On the Organ of the Soul. There, however, Kant was critical of Soemmerring's remarks. On the basis of fundamental considerations, he declared the project of finding a seat of the soul to be misguided. He justified this with the consideration that the soul could only perceive itself through the inner sense and the body only through the outer senses; from this it followed that, if it wanted to determine a place for itself, it would have to perceive itself with the same sense with which it perceived matter; but this meant that it would have to "make itself the object of its own outer perception and place itself outside itself; which contradicts itself".

In the 19th century, the search for a seat and an organ of the soul came to a halt. The term soul organ initially remained. Under the influence of new bioscientific discoveries, for example in the fields of evolutionary theory, electrophysiology and organic chemistry, materialistic and monistic models emerged that do without the term soul. For the proponents of non-materialistic models, however, the question of the place of interaction of mind and body remains topical.

Hegel

For Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, the soul is not a "finished subject", but a stage of development of the spirit. At the same time, it represents the "absolute basis of all particularity and singularity of the spirit". Hegel identifies it with the passive, receptive intellect of Aristotle, "which is everything according to possibility".

Hegel resolutely opposes the modern dualism of body and soul, the Cartesian opposition between immaterial soul and material nature. The question of the immateriality of the soul, which already presupposes this opposition, does not arise for Hegel, since he refuses to see in matter something true and in spirit a thing separate from it. Rather, in his view, the soul is "the general immateriality of nature, its simple ideal life." Hence it is always related to nature. It is only where there is corporeality. It represents the principle of movement by which corporeality is transcended towards consciousness.

In its development the soul passes through the three stages of a "natural", a "feeling" and a "real" soul. In the beginning it is a natural soul. As such it is still completely interwoven with nature and at first feels its qualities only directly. Feeling is the "healthy co-living of the individual spirit in its corporeality." It is characterized by its passivity. The transition to feeling, in which subjectivity brings itself to bear, is fluid. "The soul, as feeling, is no longer merely natural, but inward individuality." At first the feeling soul is in a state of darkness of spirit, since it has not yet sufficiently attained to consciousness and understanding. Here there is a danger that the subject will remain in a particularity of its sense of self, instead of working it out into ideality and overcoming it. Since the mind is not yet free here, mental illness may result. Only a spirit regarded as a soul in a material sense can become insane. The sentient soul makes a developmental advance when it "reduces the particularity of the feelings (also of consciousness) to a merely existing determination in it." To this it is helped by habit, which is produced as exercise. Habit is rightly called a "second nature," for it is an immediacy set by the soul alongside the original immediacy of feeling. Hegel values habit positively, in contrast to the common disparaging use of language. The characteristic of the third stage of development, the real soul, is "the higher awakening of the soul to the I, the abstract generality," whereby the I in its judgment "excludes from itself and refers to the natural totality of its determinations as an object, a world external to it," and in this totality "is immediately reflected in itself." Hegel defines the real soul as "the ideality of its determinations that exists for itself."

The controversy over the research program of psychologism

Empirical psychology as an independent discipline alongside philosophy has had antecedents since antiquity, but in the modern sense it only begins with studies developed in the 18th century.

Methodologically fundamental for the shaping of the paradigm of an empirical psychology were the works of empiricists such as John Locke (1632-1704) or David Hume (1711-1776). Hume did not attribute causation relations to ontological relations, such as rigid laws of nature, but attempted to explain them as mere habits of thought. For these empiricists, knowledge itself has its origin in mental functions. This variant of empiricism has in common with the views of early idealists and the transcendental philosophical approach of Kant in that it focuses less on metaphysical-objective, extrinsic structures than on inner-psychic, subjective structures or structures peculiar to reason itself. In this vein, Hume argued against the immortality of the soul in his treatise Of the Immortality of the Soul; he held it to be possible at most if one also assumed its preexistence. Since the soul was not a concept of experience, the question of its continued existence had to remain unanswered, and an answer was in any case irrelevant to human life.

In 1749, the physician David Hartley published his findings on the neurophysiological basis of sensory perception, imagination and the linking of thoughts. This was later joined by the development of evolutionary theoretical explanatory models by Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and others.

The moral philosopher Thomas Brown (1778-1820) wrote his Lectures on the philosophy of the human mind at the beginning of the 19th century, in which he formulated the basic laws of so-called associationism. Such methodologies combined with models of "logic" oriented to factual operations of thought rather than ideal laws of reason. In the early 19th century, Jakob Friedrich Fries and Friedrich Eduard Beneke defended such a research program, which they called psychologism, against the dominance of a philosophy of mind in the sense of Hegel. Vincenzo Gioberti (1801-1852) described as psychologism all modern philosophy since Descartes, insofar as it starts from man instead of God, i.e. does not, as he put it, follow the programme of "ontologism".

According to psychologism, philosophical investigation has only introspection as a principle of knowledge. Kant had been right in establishing the proper right of experience, but went astray when he sought a priori conditions of possibility of cognition. The psychologistic approach encountered greater difficulties with purely logical and mathematical statements than in the field of empirical knowledge. It was precisely in this field, however, that a psychologistic logic was defended in the mid-19th century. The utilitarian John Stuart Mill published his system of deductive and inductive logic in 1843. According to this system, the axioms of mathematics as well as logical principles are based solely on psychological introspection. In addition to Mill, German theorists such as Wilhelm Wundt, Christoph von Sigwart, Theodor Lipps and Benno Erdmann also worked out similarly accentuated logics. By the end of the 19th century, psychologism was the view of many psychologists and philosophers. Among them were also numerous representatives of the so-called philosophy of life. All mental or even philosophical problems were to be explained by the new means of psychology, i.e. all thought operations and their regularities were to be understood as mental functions.

Early theorists opposed Kant's thesis that psychological explanations do not settle the question of truth. The Kantian approach was defended by Rudolf Hermann Lotze for logic, Gottlob Frege for mathematics, Wilhelm Windelband and Heinrich Rickert for value ethics, Hermann Cohen and Paul Natorp for the philosophy of science. The research programs of phenomenology were also directed against psychologism. Edmund Husserl developed a fundamental critique of psychologism in his work Logical Investigations. Martin Heidegger turned the gaze not to psychological occurrences but to structures of Dasein. The same is true of most existential philosophers, such as Jean-Paul Sartre. For partly different reasons, many logical empiricists also disagreed with psychologism. One of the first among them was Rudolf Carnap. His argument was that there is not only exactly one language, the one which would be determined by psychological laws.

In addition to the work of David Hartley and Thomas Brown and the philosophers and natural scientists active in the context of psychologism in the mid to late 19th century, the work of Johann Friedrich Herbart was also decisive for the beginnings of modern psychology. Herbart was Kant's successor at his Königsberg chair from 1809.

The question of the existence of the soul

In the discussion of the 20th and 21st centuries, different determinations of the term "soul" have been proposed and a wide variety of positions have been taken on the suitability of the term and on the different concepts of soul. Roughly schematized, one can distinguish the following positions:

- a realism which understands by "soul" a substance of its own, from which thinking and feeling and other mental acts emanate and which is only temporarily bound to the body and controls it during this period. Fortexistence after bodily death is also defended by some metaphysicians and philosophers of religion. This is usually tantamount to a Platonic or Cartesian concept of the soul.

- a materialism that rejects the existence of a soul and claims that all talk of the soul is reducible to talk of physical and neural states.

- positions that are more difficult to classify in detail, which reject materialism and consider the mental not only real but also irreducible and often causally effective (for instance in the sense of a control of bodily states), but do not commit themselves to the concept of a soul in a traditional sense, especially not to its immortality.

- a decidedly antiplatonic view of some Christian theologians and philosophers who, in the sense of a holistic anthropology, regard soul and body as a unity. This unity is understood according to the substance-form principle (hylemorphism) as formulated by Aristotle and further developed by Thomas Aquinas. According to this, the soul as form of the body enters with the body into the substantial unity of the individual human being. With "form" is not meant the outer shape, but a life principle that forms the body from within.

Rejecting positions

The clearest rejection of a concept of the soul is found within the framework of eliminative materialism in philosophers such as Patricia and Paul Churchland. Everyday psychology, they argue, is a false theory that has stagnated since antiquity; nothing in reality corresponds to concepts of everyday psychology. All that exists in reality are biological processes. The philosopher Richard Rorty already tried to clarify such a position in the 1970s with a thought experiment: One could imagine an extraterrestrial civilization that used no psychological vocabulary and instead spoke only of biological states. Such a civilization would be in no way inferior to humanity in terms of its communicative abilities.

Traditional materialisms, however, do not deny the existence of mental states. They rather declare that mental states exist, but that they are nothing else than material states. Such positions are at least compatible with a very weak concept of soul: If one understands "soul" simply as the sum of ontologically unspecified mental states, then one can also use the term "soul" within the framework of such theories. For example, identity theory declares that mental states are real, but identical with brain states. This position is sometimes criticized as "carbon chauvinism" because it ties consciousness to the existence of an organic nervous system. Conscious life forms on an inorganic basis (such as silicon) would thereby be conceptually excluded in the same way as conscious artificial intelligences. In the context of the development of artificial intelligence, a materialist alternative position emerged called "functionalism". Classical functionalism is based on a computer analogy: a piece of software can be realized by very different computers (such as Turing machines and PCs), so one cannot identify a software state with a specific physical structure. Rather, software is specified by functional states that can be realized by different physical systems. In the same way, mental states are to be understood functionally; the brain thus offers only one of many possible realizations. After some changes of opinion, Daniel Dennett also advocates functionalism: a conscious human mind is more or less a serial virtual machine mounted - inefficiently - on the parallel hardware that evolution has provided us with.

Objections against identity theory and functionalism essentially arise from the epistemological debate about the structure of reductive explanations. If one wants to attribute a phenomenon X (such as mental states) to a phenomenon Y (such as brain states or functional states), one would have to be able to make all the properties of X intelligible through the properties of Y. This is the case, for example, in the case of mental states. Now, mental states have the property of being experienced in a certain way - it feels a certain way to be in pain, for example (cf. qualia). This aspect of experience, however, could not be explained in either a neuroscientific or a functional analysis. Reductive explanations of the mental must therefore inevitably fail. Such problems have led to the development of numerous non-reductive materialisms and monisms in the philosophy of mind, whose representatives assume a "unity of the world" without committing themselves to reductive explanations. Examples of these can be found in the context of emergent theories, and occasionally David Chalmers' property dualism is counted among these approaches. However, it is controversial to what extent such positions can still be considered materialisms, since the boundaries to dualistic, pluralistic or generally anti-ontological approaches are often blurred.

Non-materialist positions

In modern philosophy of mind, dualistic positions are also held. One type of argument here refers to thought experiments in which one imagines oneself disembodied. A corresponding consideration by Richard Swinburne can be rendered in everyday language as follows: "We can imagine a situation in which our body is destroyed but our consciousness persists. This stream of consciousness requires a vehicle or substance. And for this substance to be identical with the person before bodily death, there must be something that connects one phase with the other. Since the body is destroyed, this something cannot be physical matter: so there must be something immaterial, and this we call soul." William D. Hart, for example, has also defended a Cartesian dualism by arguing that we can imagine ourselves to be without bodies, but nonetheless retain our actor-causality; since imaginability is possible, we ourselves can therefore exist without bodies, so we ourselves are not necessarily, and thus not actually, bound to matter.

John A. Foster defends a similar dualistic position. For this he rejects an eliminative materialism. Whoever denies mental states is himself in a mental state and makes a meaningful statement, which itself already implies mental phenomena. Behaviorist reductions failed because of having to specify behavioral states by mental states as well. Moreover, Foster puts forward a variant of the knowledge argument: If these materialisms were true, a person blind by birth could grasp the content of color perceptions, but this is ruled out. Similar problems, he argues, are associated with reductions to functional roles, as advocated by Sydney Shoemaker, and in the more complicated variant of functional profiles, by David M. Armstrong and David K. Lewis, and with theories of type identity. In particular, mental states with the same functional roles could not be sufficiently distinguished. Even a distinction such that phenomenal content is captured by introspection, neurophysiological type by scientific terms (an idea developed by Michael Lockwood), could not explain why materially identical entities are related to different experiences. Instead of such token and type identity theories, a Cartesian interactionism of soul and body would have to be adopted. To this end, the argument (by Donald Davidson) that no strict laws are conceivable here is rejected. Since material objects could not possess mental states, because only mental properties constitute that a mental state belongs to an object, a non-physical soul has to be assumed. This soul can only be characterized directly (ostensively), not by attributes such as "thinking" (because it can, for example, only possess unconscious occult mental states at one point in time). Moreover, a person is - against John Locke - identical with the subject of phenomenal states.

The radical position that reality consists only of the psychic, a so-called immaterialism, is also represented in modern debates, for example by Timothy Sprigge.

Gilbert Ryle

Gilbert Ryle thinks that it is tantamount to a category mistake to speak of the mental as of the material. It is just as nonsensical to look for a spirit next to the body as it is to look for something called "the team" next to the individual players of a football team entering a stadium. The team, in fact, does not exist alongside the individual players, but is made up of them. Depending on whether one conceives of "the team" as a purely conceptual (unreal) construct or ascribes to it a reality of its own (universality problem), one arrives at different answers regarding the "reality" of the existence of a soul. Essentially, Ryle thereby ties in with the Aristotelian definition, according to which the soul is to be understood as a principle of form of the material, especially of the living, which cannot exist apart from the body.

Possible properties of the soul

Simplicity

The traditional concept of an immortal soul presupposes that it does not consist of parts into which it can be disassembled, otherwise it would be transient. On the other hand, it is said to have complex interaction with the environment, which is not compatible with the idea that it is absolutely simple and unchanging. Swinburne therefore assumes, as part of his dualistic concept, that the human soul has a continuous, complex structure. This he infers from the possible stability of a system of interrelated views and desires of an individual.

Ludwig Wittgenstein has held "that the soul - the subject, etc. - as conceived in today's superficial psychology is an unding. For a compound soul would no longer be a soul."

Roderick M. Chisholm has taken up again the idea of the "simplicity" (in the sense of non-composition) of the "soul". In doing so, he understands "soul" to be synonymous with "person" and claims that this is also the word meaning intended by Augustine, Descartes, Bernard Bolzano, and many others. In this sense, he defends, as he does in other wordings on the theory of subjectivity, that our being is fundamentally different in nature from the being of composite entities.

afterlife

While materialists deny the existence of a soul and many dualists no longer understand the term soul in a traditional sense, the question of a post-mortal survival has been debated again in recent decades and in part answered positively. Lynne Rudder Baker distinguishes seven metaphysical positions that affirm the continued existence of a personal identity after death:

- Immaterialism: the continuity of the person is based on the identity of the soul before and after death.

- Animalism: the continuity of the person is based on the identity of the living organism before and after death.

- Thomism: the continuity of the person is based on the identity of the composite of body and soul before and after death.

- Memory theories: a person is exactly the same before and after death if there is mental continuity

- Soul as "software": the selfhood of the person is analogous to that of a software independent of hardware (in this case the brain).

- Soul as information-bearing pattern: the selfhood of the person is based on the selfhood of an information pattern which is carried by the body matter and can be restored after the death of the person.

- Constitutional Theories

Baker discusses the extent to which these positions are suitable as a metaphysical basis for Christian belief in the resurrection. In doing so, she rejects the first six positions and then defends a variant of the seventh.

The soul as a whole and its relationship to the spirit

Apart from the discussion between dualists and materialists, a concept of soul has developed in the German-speaking world, which primarily draws its definition from the fact that it demarcates the soul as a wholeness from the spirit and its multiplicity of objective contents.

For Georg Simmel, spirit is "the objective content of what becomes conscious within the soul in living function; soul is, as it were, the form that spirit, i.e., the logical-conceptual content of thought, assumes for our subjectivity, as our subjectivity." Spirit, then, is objectified soul. Its contents are present in parts, while the soul always constitutes the unity of the whole man.

Helmut Plessner sees it similarly, for whom the soul constitutes the wholeness of man with all desires and wills and all unconscious urges. The spirit often has the task of serving the soul in the satisfaction of its desires: "Spirit is grasped by an individual, unjustifiable center of the soul, which at least knows itself in this way, and also acts in this way alone on the physical sphere of existence." By this, however, Plessner does not mean the connection between body and intellect that goes back to Nietzsche, in which the intellect has the task of ensuring that the body's natural needs are satisfied. Spirit, for Plessner, means the full cultural content of all human relations of self and world. While man, due to his eccentric positionality, can indeed make individual contents of his spirit graspable for himself in objectified form, this is denied him for his soul, for he can never bring himself before himself as a whole and reflect upon himself.

Oswald Spengler also emphasizes the unity of the soul: "It would be easier to dissect a theme by Beethoven with a dissecting knife or acid than to dissect the soul by means of abstract thought." All attempts to represent the soul, he says, are only images that never do justice to their subject. Following Nietzsche's strong subjectivism, Spengler also transfers the concept of the soul to cultures: "Every great culture begins with a basic conception of the world; it has a soul with which it confronts the world in a formative way. Cultures form their own spiritual and material "reality as the epitome of all symbols in relation to a soul".

Ernst Cassirer discusses the soul within the framework of his philosophy of symbolic forms. He thinks that every symbolic form does not have the boundary between ego and reality as a fixed one in advance, but sets it itself first. For this reason, he argues, it must also be assumed for myth "that it does not start out with a finished concept of the I or of the soul any more than with a finished image of objective being and events, but that it must first gain both, first form them out of itself." A conception of the soul is formed only slowly in the process of culture. In order for this to happen, man must first separate himself from the ego and the world, understand himself as ego and soul, and detach himself from the overall context of nature. The ideas of a soul as a unity are only late concepts in religion as well as in philosophy.

In Ludwig Klages, the relationship between spirit and soul becomes an antagonism that inevitably arises from the nature of the two poles. In his three-volume magnum opus Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele (The Spirit as the Adversary of the Soul), Klages, who is strongly influenced here by Friedrich Nietzsche, explains in detail his thesis that the spirit and the life principle, the soul, are "hostilely opposed to each other". The spirit, which produces philosophical and scientific systems, is rigid, static, and alienated from reality. It builds the dungeon of life. The soul, on the other hand, is constantly changing and is capable of surrendering to reality in deep experience. It is transient and should affirm its transience as the "commandment of dying" and the prerequisite of all life. The idea of an immortal soul is a product of the spirit that is hostile to life.

Depth psychological considerations

Freudian psychoanalysis

Regarding the task of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud stated in 1914 that it had not yet claimed to "give a complete theory of human soul life at all"; even metapsychology, as a later attempt at this sense, remained in the state of a torso due to the still lacking scientific possibilities. Freud wrote that the terms "soul" and "psyche" were used synonymously in the context of this theory, and that two things were known of the life of the soul: the brain with the nervous system as biological organs, and the acts of consciousness, which refer to corporeality as the locus of psychic processes. The acts of consciousness, however, were given immediately and could therefore not be brought closer to man by any description. An empirical relation between these "two endpoints of our knowledge" is not given, and even if it existed, it could only contribute to the localization of the processes of consciousness, not to their understanding. The life of the soul, he said, was the function of the "psychic apparatus," which was spatially extended and composed of several pieces, much like a telescope or microscope. The instances or districts of soul life were the id, the ego, and the superego. Freud suggested that spatiality was a projection of the extension of the psychic apparatus, whose conditions had to replace Kant's a priori. On this Freud noted in 1938, "Psyche is extended, knows nothing of it." He believed that philosophy must take into account the results of psychoanalysis "in the most extensive way" insofar as it was based on psychology. It must modify its hypotheses about the relation of the soul to the body accordingly. Up to now - Freud wrote this in 1913 - philosophers had not dealt with the "unconscious activities of the soul" in an appropriate way, because they had not known their phenomena.

Freud believed that his general scheme of the psychic apparatus also applied to the "higher animals that are psychically similar to man. Thus, in animals that had been in a relationship of childlike dependence with man for a long time, a superego was to be assumed. Animal psychology should investigate this. In fact, the study of animal behaviour from a psychological point of view experienced an upswing in the first half of the 20th century. Animal psychology, which was later called ethology, developed into an independent field.

Jungian Analytical Psychology

Carl Gustav Jung, in his study Psychological Types published in 1921, gave a definition of the term "soul" within the framework of the terminology he used. He distinguished between soul and psyche. He described the psyche as the totality of all - conscious and unconscious - mental processes. The soul he described as "a definite, delimited complex of functions which might best be characterized as a personality." A distinction had to be made between the outer and the inner personality of man; Jung equated the inner with the soul. The outer personality, he said, was a "mask" shaped by the intentions of the individual and by the demands and opinions of his environment. Taking up the ancient Latin term for actors' masks, Jung called this mask persona. The inner personality, the soul, was "the way in which one relates to the inner psychic processes," his inner attitude, "the character he turns toward the unconscious." Jung formulated the principle that the soul is complementary to the persona. It contains those generally human qualities which the persona lacks. Thus, to an intellectual persona belongs a sentimental soul, to a hard, tyrannical, inaccessible persona a dependent, impressionable soul, to a very masculine persona a feminine soul. Therefore, the character of the soul, which is hidden from the outside and often unknown to the consciousness of the person concerned, can be deduced from the character of the persona.

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch of the cerebral ventricles, Codex Windsor, 1489

René Descartes, painting after an original by Frans Hals from the second half of the 17th century, now in the Louvre.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a soul?

A: A soul is believed to be the supernatural part of a living human being that lives on after death.

Q: Can science discover the soul?

A: No, because the soul cannot be tested in any controlled way.

Q: What is reincarnation?

A: Reincarnation is the belief that after the body dies, the soul will be born again in another body. It is important to Hinduism.

Q: What do Buddhists believe about the soul?

A: Buddhists do not believe in an eternal soul or essence in phenomena. They believe in transmigration or rebirth based on their understanding of karma and nirvana.

Q: What is resurrection?

A: Resurrection is the Christian belief that a soul returns in the same body.

Q: Who do Christians believe was resurrected?

A: In most Christian denominations, Jesus Christ was resurrected but it is also promised for all souls.

Q: What do atheists believe about the soul?

A: Most atheists do not believe in the concept of a soul and believe that the body is the only part of a person.

Search within the encyclopedia