Socrates

![]()

This article is about the philosopher Socrates; for other meanings, see Socrates (disambiguation).

Socrates (ancient Greek Σωκράτης Sōkrátēs; * 469 BC in Alopeke, Athens; † 399 BC in Athens) was a Greek philosopher fundamental to Western thought who lived and worked in Athens at the time of the Attic Democracy. In order to gain knowledge of human nature, ethical principles and understanding of the world, he developed the philosophical method of structured dialogue, which he called Maieutics ("midwifery").

Socrates himself left no written works. The tradition of his life and thought is based on the writings of others, mainly his students Plato and Xenophon. They wrote Socratic dialogues and emphasized different features of his teaching in them. Any account of the historical Socrates and his philosophy is therefore incomplete and fraught with uncertainties.

Socrates' outstanding importance can be seen above all in his lasting impact within the history of philosophy, but also in the fact that the Greek thinkers before him are today called pre-Socratics. His posthumous fame was greatly enhanced by the fact that, although he did not accept the reasons for the death sentence imposed on him (alleged corrupting influence on youth as well as disrespect for the gods), he refrained from evading execution by flight out of respect for the law. Until his execution by hemlock, philosophical questions occupied him and his visiting friends and students in prison. Most of the important schools of philosophy in antiquity referred to Socrates. Michel de Montaigne in the 16th century called him the "master of all masters," and Karl Jaspers wrote: "To have Socrates before one's eyes is one of the indispensable conditions of our philosophizing."

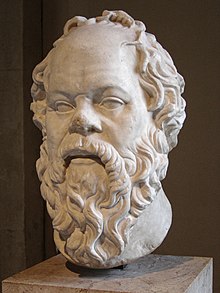

Bust of Socrates, Roman copy of a Greek original, 1st century, Louvre, Paris

Center of an intellectual-historical turn

Socrates was the first to call philosophy down from heaven to earth, to settle it among men and to make it an instrument for testing ways of life, customs and values, remarked the Roman politician Cicero, who was an excellent connoisseur of Greek philosophy. In Socrates he saw personified the abandonment of Ionian natural philosophy, which until 430 B.C. had been prominently represented in Athens by Anaxagoras. The latter's principle of reason had impressed Socrates, but he missed in Anaxagoras the application of reason to human problems. However, contrary to Cicero's belief, Socrates was not the first or the only one to place human concerns at the center of his philosophical thought.

During Socrates' lifetime, Athens, as the supreme power in the Attic League and as a result of the development of Attic democracy, was the cultural centre of Greece, subject to profound political and social change and a variety of tensions. Therefore, there were good opportunities for new intellectual currents to develop there in the 5th century BC. One such broadly based intellectual movement, which also emerged effectively through teaching, was that of the Sophists, with whom Socrates had so much in common that he himself was often regarded as a Sophist by his contemporaries: the practical life of the people, questions of the polis and legal order as well as the position of the individual within it, the critique of traditional myths, the examination of language and rhetoric, as well as the meaning and content of education - all this also occupied Socrates.

What distinguished him from the sophists and made him a founding figure in intellectual history were the additional characteristics of his philosophizing. Characteristic, for example, was his constant, probing effort to get to the bottom of things and, in the case of questions such as "What is bravery?", not to be satisfied with the superficial-obvious, but to bring up the "best logos", that is, the unchanging essence of the thing, independent of time and place.

Methodologically new in his time was the maieutics, the procedure of philosophical dialogue introduced by Socrates for the purpose of gaining knowledge in an open-ended research process. Another original Socratic method was questioning and researching in order to establish philosophical ethics. Among the results achieved by Socrates was that right action follows from right insight and that justice is a basic condition for a good state of the soul. From this he concluded that doing wrong is worse than suffering injustice.

A fourth element of the philosophical new beginning associated with Socrates is linked to this: the significance and proving of philosophical insights in the practice of life. In the trial that ended with his death sentence, Socrates certified to his opponents that they were recognizably in the wrong. Nevertheless, he subsequently refused to escape from prison so as not to put himself in the wrong in his turn. He weighted the philosophical way of life and the adherence to the principle that doing wrong is worse than suffering wrong more highly than the possibility of preserving his life.

Bust of Socrates in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples

Basic features of Socratic philosophy

What would remain of the philosopher Socrates without the works of Plato, asks Günter Figal. He answers: an interesting figure of Athenian life in the fifth century BC, hardly more; secondary perhaps to Anaxagoras, definitely to Parmenides and Heraclitus. Plato's central position as a source of Socratic thought poses the problem of a demarcation between the two imaginative worlds, for Plato is represented in his works as a philosopher in his own right at the same time. There is widespread agreement in research that the early Platonic dialogues - the Apology of Socrates, Charmides, Criton, Euthyphron, Gorgias, Hippias minor, Ion, Laches and Protagoras - show the influence of Socratic thought more clearly, and that the independence of Plato's philosophy is more pronounced in his later works.

The core areas of Socratic philosophizing include, in addition to the quest for knowledge based on dialogues, the approximate determination of the good as a guideline for action and the struggle for self-knowledge as an essential prerequisite for a successful existence. The image of Socrates conversing in the streets of Athens from morning till night is to be extended by phases of complete mental absorption, with which Socrates also made an impression on his fellow citizens. An extreme example of this trait is Alcibiades' description of an experience in Potidaia, which is contained in Plato's Symposion:

"At that time on the campaign [...] he stood, absorbed in some thought, on the same spot from the morning onwards and pondered, and when he did not succeed, he did not give way, but remained standing pondering. In the meantime it had become noon; then the people noticed it, and, astonished, one told the other that Socrates had been standing there since the morning, thinking about something. Finally, when it was already evening, some of the Ionians, when they had eaten, carried out their sleeping cushions; so they slept in the coolness, and at the same time could observe whether he would remain standing there during the night. And indeed, he remained standing until morning came and the sun rose! Then he made his prayer to the sun and went away."

Socratic conversation, in turn, was clearly related to erotic attraction. Eros as one of the forms of Platonic love, presented in the Symposion as a great divine being, is the mediator between mortals and immortals. Günter Figal interprets: "The name of Eros stands for the movement of philosophy that transcends the realm of the human. [...] Socrates can philosophize best when he is taken in by the wholly unsublimated beautiful. Socratic conversation does not take place after once having succeeded in ascending to that nonsensical height where only ideas appear as the beautiful; rather, it continually performs within itself the movement from the human to the superhuman beautiful, and dialogically ties the superhuman beautiful back to the human."

Sense and method of Socratic dialogues

→ Main article: Socratic method

"I know that I do not know" is a well-known but highly abbreviated formula that clarifies what Socrates had ahead of his fellow citizens. For Figal, Socrates' insight into his philosophical not-knowing (aporia) is at the same time the key to the object and method of Socratic philosophy: "In Socratic speech and thought lies forced renunciation, a renunciation without which there would be no Socratic philosophy. This arises only because Socrates cannot get anywhere in the realm of knowledge and takes flight into dialogue. Socratic philosophy has become dialogical in its essence because exploratory discovery seemed impossible." Inspired by the philosopher Anaxagoras, Socrates originally took a special interest in the study of nature and, like the latter, grappled with the question of causes. He was puzzled, however, as Plato also relays in the dialogue Phaidon, because there were no clear answers. Human reason, on the other hand, through which everything we know about nature is mediated, could not explain Anaxagoras. Therefore, Socrates turned away from the search for causes to understanding based on language and thought, as Figal concludes.

The goal of the Socratic dialogue in the form handed down by Plato is the common insight into a matter on the basis of question and answer. According to this, Socrates did not accept rambling speeches about the object of investigation, but insisted on a direct answer to his question: "In Socratic conversation, the question has priority. The question contains two moments: it is an expression of the questioner's ignorance and an appeal to the interviewee to answer or admit his own ignorance. The answer provokes the next question, and in this way the dialogical inquiry gets under way." By asking questions, then - and not by lecturing the interlocutor, as the sophists practiced towards their students - insightfulness was to be awakened, a method which Socrates - according to Plato - called maieutics: a kind of "spiritual obstetrics." For the change of the previous attitude as a result of intellectual debate depended on the insight itself being attained or "born".

The progress of knowledge in the Socratic dialogues occurred in a characteristic gradation: In the first step, Socrates sought to make it clear to the respective discussion partner that his way of life and way of thinking were inadequate. In order to show his fellow citizens how little they had previously thought about their own views and attitudes, he then confronted them with the nonsensical or unpleasant consequences that would result. According to the Platonic Apology, the Oracle of Delphi imposed upon Socrates the testing of the knowledge of his fellow men. According to Wolfgang H. Pleger, Socratic dialogue thus always includes the three moments of examination of the other, self-examination, and factual examination. "The philosophical dialogue begun by Socrates is a zetetic, that is, investigative, procedure. The refutation, the elenchos (ἐλεγχος), is inevitably incidental. It is not the motive."

After this uncertainty, Socrates challenged his interlocutor to rethink. He directed the conversation to the level of the question of what is essential in the human being, linking it to the subject of discussion - be it, for example, bravery, prudence, justice or virtue in general. Insofar as the interlocutors did not break off the dialogue, they came to the conclusion that the soul, as the actual self of man, must be as good as possible and that this depends on the extent to which man does the morally good. What the good is, then, is to be found out.

For the dialogue partners, Plato regularly showed in the course of the investigation that Socrates, who nevertheless pretended not to know, soon revealed clearly more knowledge than they themselves possessed. At the beginning often in the role of the seemingly inquisitive student, who suggested the role of teacher to his counterpart, he proved to be clearly superior in the end.

Because of this approach, Socrates' initial position was often perceived as untrustworthy and insincere, as an expression of irony in the sense of dissimulation for the purpose of misleading. Döring nevertheless considers it uncertain that Socrates began to play ironically with his non-knowledge in the sense of deliberate deep fakery. Like Figal he assumes in principle seriousness of the statement. But even if Socrates was not concerned with a public dismantling of his interlocutors, his action must have turned many of those he addressed against him, especially since his students also practiced this form of dialogue.

However, Martens rejects the idea of a uniform Socratic method as a philosophical-historical dogma going back to Plato's student Aristotle, which says that Socrates only conducted "examining" conversations, but no "eristic" argumentative conversations or "didactic" doctrinal conversations. On the other hand, according to Martens, Xenophon's statement is correct that Socrates adapted the conduct of the conversation to the respective interlocutors, i.e. in the case of the Sophists to the refutation of their pretended knowledge (Socratic elenctic), but in the case of his old friend Kriton to a serious search for truth.

Another characteristic moment of Socratic conversation as presented in Plato is the fact that the course of inquiry often does not move in a straight line from the refutation of adopted opinions to a new horizon of knowledge. In Plato's dialogue Theaetetus, for example, three definitions of knowledge are discussed and found wanting; the question of what knowledge is remains open. Sometimes it is not only the interlocutors who fall into perplexity, but also Socrates, who himself has no conclusive solution to offer. Thus, not infrequently, "confusion, vacillation, astonishment, aporia, breaking off of the conversation" appear.

The question of justice in Socratic dialogue

A particularly broad spectrum of investigation unfolds in both Plato and Xenophon in their Socratic dialogues devoted to the question of justice. Justice is not only examined as a personal virtue, but social and political dimensions of the topic are also addressed.

The example of Plato

In the so-called Thrasymachus dialogue, the first book of Plato's Politeia, there are three partners, one after the other, with whom Socrates pursues the question of what is just or what justice consists of. The conversation takes place in the presence of two of Plato's brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantos, in the house of the rich Syracusan Kephalos, who has taken up residence in the Athenian port of Piraeus at the invitation of Pericles.

After introductory remarks about the relative advantages of old age, the householder Cephalus is asked to tell Socrates what he values most about the wealth he has been granted. It is the associated possibility of not owing anyone anything, replies Cephalus. This raises the question of justice for Socrates, and he poses the problem of whether it is just to return weapons to a fellow citizen from whom one has borrowed them, even if he has meanwhile gone mad. Hardly, says Cephalus, who then withdraws and leaves the continuation of the conversation to his son Polemarchus.

Referring to the poet Simonides, Polemarchus says that it is just to give everyone what he is guilty of, not weapons to the madman, but good things to friends and evil things to enemies. This presupposes, Socrates objects, that one knows how to distinguish between good and evil. In the case of physicians, for example, it is clear in what they need expertise, but in what do the righteous? In matters of money, Polemarchus retorts, but cannot hold his own with it. By arguing that a true expert must be versed not only in the matter itself (the right use of money) but also in its opposite (embezzlement), Socrates throws Polemarchus into confusion. Moreover, in distinguishing between friends and enemies, Socrates adds, it is easy to make a mistake due to a lack of knowledge of human nature. Moreover, it is not the business of the just to harm anyone at all. With this negative finding, the inquiry returns to its starting point. Socrates asks, "But since it has been shown that even this is not justice, nor the just, what else can anyone say it is?"

Now the sophist Thrasymachus, who has not yet had his say, intervenes in an inflammatory manner. He declares everything that has been said so far to be idle chatter, criticizes Socrates for only questioning and refuting instead of developing a clear idea of his own, and offers to do so in turn. With the support of the others present, Socrates accepts the offer and only humbly objects to Thrasymachus' reproaches that he cannot rush forward with answers who does not know and does not pretend to know: "So it is far cheaper for you to talk, since you claim that you know and that you can recite it."

Thrasymachus then determines what is just as what is beneficial to the stronger and justifies this with the legislation in each of the various forms of government, which corresponds either to the interests of tyrants or those of aristocrats or those of democrats. In response to Socrates' question, Thrasymachus confirms that the obedience of the governed to the governors is also just. But by getting Thrasymachus to admit the fallibility of the rulers, Socrates succeeds in undermining the latter's whole construct, for if the rulers err in what is proper for them, even the obedience of the ruled does not lead to justice: "Does it not then necessarily come out that it is just to do the opposite of what you say? For that which is unjust to the stronger is then commanded to be done by the weaker. - Yes by Zeus, O Socrates, said Polemarchus, this is quite evident."

Thrasymachus, however, does not see himself convinced, but outwitted by the way he asks the question, and insists on his thesis. Using the example of the physician, however, Socrates shows him that a true administrator of one's own profession is always oriented towards the benefit of the other, in this case the sick person, and not towards one's own: consequently, the capable rulers are also oriented towards what is beneficial for the ruled.

After Thrasymachus has also failed to show that the just man pays too little attention to his own advantage to achieve anything in life, while the tyrant who carries injustice to extremes on a grand scale gains the greatest happiness and prestige from it - that justice therefore stands for naivety and simplicity, but injustice for prudence - Socrates directs the conversation to the consideration of the balance of power between justice and injustice. There, too, it finally emerges against the view of Thrasymachus, injustice has a bad standing: unjust people are at odds with one another and disintegrate with themselves, Socrates thinks, so how are they to get anywhere in war or peace against a polity in which the concord of the just prevails? Apart from this, for Socrates justice is also the prerequisite of individual well-being, of eudaimonia, for it has the same significance for the well-being of the soul as the eyes have for sight and the ears for hearing.

Thrasymachus finally agrees with the result of the discussion in everything. Socrates, however, regrets at the end that he, too, has not reached a conclusion on the question of what constitutes the just in its essence, despite all the ramifications of the discussion.

Xenophon's dialogue variant

In the dialogue on justice and self-knowledge handed down by Xenophon, Socrates endeavours to make contact with the still young Euthydemos, whom he is urging onto the political stage. Before Euthydemos agrees to talk, he has already repeatedly drawn Socrates' ironic remarks about his inexperience and unwillingness to learn. One day, when Socrates addresses him directly about his political ambitions and refers to justice as a qualifier, Euthydemos affirms that one cannot even be a good citizen without a sense of justice and that he himself possesses no less of it than anyone else.

Thereupon Socrates, Xenophon continues, begins to question him at length about the distinction between just and unjust actions. The fact that a general allows property to be plundered and robbed in an unjust enemy state seems just as just to Euthydemos in the course of the conversation, just as he generally regards as just everything towards enemies that would be unjust towards friends. But even friends are not owed sincerity in every situation, as is shown by the example of the commander who falsely announces the imminent arrival of confederates to his discouraged troops in order to strengthen their morale in battle. To Euthydemos, who is already greatly unsettled, Socrates now poses the question of whether an intentional or an unintentional false statement is the greater wrong if friends are harmed by it. Euthydemos decides in favour of deliberate deceit as the greater wrong, but is also refuted in this by Socrates: He who deceives in his own ignorance is obviously ignorant of the right way and, in doubt, disoriented. According to Xenophon, Euthydemus also finds himself in this situation: "Ah, best Socrates, by all the gods, I have put all my effort into studying philosophy, because I believed that this would train me in everything that a man who aspires to higher things needs. Now I have to realize that with what I have learned so far I am not even able to answer what is vital to know, and there is no other way that would lead me further! Can you imagine how despondent I am?"

Socrates takes this admission as an opportunity to refer to the oracle of Delphi and to the temple inscription: "Know thyself!" Euthydemos, who has already visited Delphi twice, confesses that the invitation has not preoccupied him in the long term, because he already thought he knew enough about himself. This is where Socrates intervenes:

"What is your opinion: who knows himself better: he who knows only his name, or he who does as the buyers of horses do? They believe that they do not know a horse until they have examined whether it is obedient or stubborn, strong or weak, fast or slow, and in general whether it is useful or useless in everything that is expected of a horse. In the same way, it is only he who has submitted himself to the test of how far he can do justice to the tasks approaching man who knows his strength."

Euthydemos agrees with this; but this is not enough for Socrates. He wants to point out that self-knowledge brings the greatest advantages, but self-deception brings the worst disadvantages:

"For he who knows himself knows what is useful for him, and is able to distinguish what he can and cannot do. He who pursues what he understands acquires what he needs, and it goes well with him; on the other hand, he keeps away from what he does not understand, and so he commits no mistakes and is preserved from mischief."

The correct self-assessment also forms the basis for the standing in which one is held by others and for successful cooperation with like-minded people. Those who do not have it usually go wrong and make a mockery of themselves.

"Even in politics, after all, you see that states that misjudge their power and get involved with more powerful opponents are doomed to either destruction or enslavement."

Now Xenophon shows Euthydemos as an inquisitive pupil who is urged by Socrates to take up self-exploration by worrying about the determination of the good in distinction from the bad. At first Euthydemos sees no difficulty in this; he lists health, wisdom, and happiness one after the other as characteristics of the good, but each time he has to accept Socrates' relativization: "Thus it seems, dear Socrates, that happiness is the least contested good."-"Unless someone, dear Euthydemos, builds it up on doubtful goods." Socrates then conveys to Euthydemos beauty, power, wealth, and public renown as dubious goods in relation to happiness. Euthydemos admits to himself, "Yes truly, if I am not right even in praising happiness, then I must confess that I do not know what to ask of the gods."

Only now does Socrates direct the conversation to Euthydemos' main area of interest: his aspired leadership role as a politician in a democratic state. Socrates wants to know what Euthydemus can say about the nature of the people (demos). He is familiar with the rich and the poor, says Euthydemos, who counts only the poor among the people. "Whom do you call rich, whom poor?" asks Socrates. "He who does not possess the necessaries of life I call poor; he whose possessions exceed these I call rich." - "Have you ever made the observation that some who possess but little are content with what little they have, and even give of it, while others, in considerable wealth, have not yet enough?"

Then it suddenly occurs to Euthydemos that some violent people commit injustice like the poorest of the poor, because they cannot manage with what belongs to them. Socrates concludes that tyrants must be counted among the people, while the poor, who know how to manage their possessions, must be counted among the rich. Euthydemos concludes the dialogue: "My poor judgment compels me to admit the conclusiveness even of this proof. I know not, perhaps it is best that I say no more; I am but in danger of being at my wits' end within a short time."

Finally, Xenophon mentions that many of those whom Socrates had similarly rebuked subsequently stayed away from him, but not Euthydemos, who henceforth thought that he could only become a capable man in Socrates' company.

Approach to goodness

According to Plato's Apology, Socrates developed the unchallengeable core of his philosophical work to the jurors in the trial by announcing remonstrances to each of them in case of acquittal in a future encounter:

"Best of men, you, a citizen of Athens, the greatest and most famous city in wisdom and strength, you are not ashamed to worry about treasures, to possess them in as great a quantity as possible, also about reputation and prestige, on the other hand about insight and truth and about your soul, that it may become as good as possible, therefore you do not worry and reflect? But if any one of you objects and says that he does care, I will not immediately desist from him and go on, but I will question him and try him and search him out, and if he does not seem to me to possess efficiency, but says he does, I will reproach him for esteeming the most valuable least, but the worse more highly."

Only knowledge of the good serves one's own best and enables one to do good, for according to Socrates' conviction no one knowingly does evil. Socrates denied that anyone can act against his own better knowledge. He thus denied the possibility of "weakness of will," which was later referred to by the technical term akrasia coined by Aristotle. In antiquity, this assertion was one of the best-known guiding principles of the doctrine attributed to Socrates. At the same time, it is one of the so-called Socratic paradoxes, because the thesis does not seem to agree with the common experience of life. In this context, Socrates' claim of not knowing also appears paradoxical.

Martens differentiates Socratic non-knowledge. According to this, it is first to be understood as a rejection of sophistical knowledge. In the knowledge examinations of politicians, craftsmen, and other fellow citizens, too, it shows itself as demarcating knowledge, as a "rejection of a knowledge of the arete based on conventions". In a third variant, it is a not-yet-knowledge that encourages further testing, and finally, it is demarcation from an evidential knowledge of the good life or of the right way to live. According to this, Socrates was convinced that "with the help of common rational reflection, one could go beyond a merely conventional and sophistical illusory knowledge to at least provisionally tenable insights".

According to Döring, this apparent contradiction between insight and ignorance is resolved as follows: "When Socrates declares it impossible in principle for a human being to attain knowledge of what is good, pious, just, etc., then he means a universally valid and infallible knowledge that provides immutable and unchallengeable norms for action. Such knowledge, in his view, is fundamentally denied to man. What man alone can attain is a partial and provisional knowledge which, however secure it may seem at the moment, nevertheless always remains conscious that it may prove in retrospect to be in need of revision." To strive for this imperfect knowledge in the hope of coming as near as possible to the perfected good is consequently the best thing man can do for himself. The farther he advances in it, the happier he will live.

Figal, on the other hand, interprets the question of the good as pointing beyond man. "In the question of the good lies actually the service to the Delphic god. The idea of the good is ultimately the philosophical meaning of the Delphic oracle."

Last things

In the closing words that Socrates addressed in court, according to Plato's account, to the part of the jury that was favorable to him, he justified the intrepidity and firmness with which he accepted the verdict, referring to his Daimonion, which had at no time warned him against any of his actions in connection with the trial. His expressions of impending death express confidence:

"It must be that it is something good that has happened to me, and it is impossible for us to suppose rightly if we think that dying is an evil. [...] But let us also thus consider how great the hope is that it is something good. Being dead is one of two things: either it is a non-being, and we have no more sensation after death - or it is, as the legend goes, some transfer and emigration of the soul from the place here to another. And if there is no sensation at all, but a sleep, as when one sleeps and sees no dream-image, then death would be a wonderful gain [...], for then eternity would seem no longer than a night. If, on the other hand, death is like an emigration from here to another place, and if the legend is true that all those who have died dwell there altogether, what good would be greater than this, you judges? For if one should go to the kingdom of Hades, and, being rid of these here who call themselves judges, should there meet the true judges, who, as the legend relates, do justice there, Minos, Rhadamanthys, and Aiakos, and Triptolemos, and all the other demigods who have proved themselves just in their lives, would the journey thither be to be despised? And even to have intercourse with Orpheus, and Musaios, and Hesiod, and Homer, at what price would any of you purchase that?"

Socrates was no different to the friends who visited him on his last day in prison, according to Plato's dialogue Phaidon. Here the issue is trust in the philosophical logos "even in the face of the utterly unthinkable," according to Figal; "and since the extreme situation only brings to light what is also otherwise true, this question is that of the trustworthiness of the philosophical logos in general. It becomes the ultimate challenge for Socrates to make a case for it."

The question of what happens to the human soul at death was also discussed by Socrates in his last hours. The argument against its mortality was that it was bound to life, but life and death were mutually exclusive. However, it could disappear as well as dissipate at the approach of death. Figal sees this as a confirmation of the open perspective on death adopted by Socrates before the court and concludes: "Philosophy has no ultimate ground into which it can go back, justifying itself. It proves to be abysmal when one asks for final grounds, and therefore, where its own possibility is at stake, it must be rhetorical in its own way: Its logos must be represented as the strongest, and this is best done with the persuasiveness of a philosophical life - by showing how one trusts the logos and engages in what the logos is supposed to represent."

Eros, Attic red-figure double disc by the painter of London D 12, c. 470/50 BC, Louvre

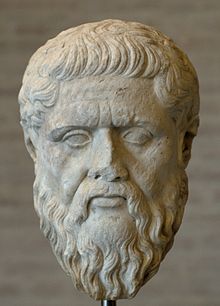

Bust of Plato (Roman copy of the Greek portrait of Plato by Silanion, Glyptothek Munich)

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Socrates?

A: Socrates was a Greek philosopher who lived from 469 BC to 399 BC.

Q: What did Socrates do?

A: Socrates used argument, debate, and discussion to help people understand difficult issues. He mainly dealt with moral questions about how life should be lived.

Q: How influential was Socrates?

A: Socrates had a great influence on philosophy and all philosophers before him are referred to as Presocratic philosophers.

Q: When did he live?

A: Socrates lived from 469 BC to 399 BC.

Q: Did he propose any specific knowledge or policy?

A: No, Socrates did not propose any specific knowledge or policy.

Q: What kind of issues did he deal with? A: The issues that Socrates dealt with were mostly moral questions about how life should be lived, although they appeared political on the surface.

Q: Are there any other names for philosophers before him? A: Yes, philosophers before him are called the Presocratic philosophers.

Search within the encyclopedia