Snake River

![]()

This article is about the Snake River, tributary of the Columbia River, in the western United States. For other rivers of this name, see Snake River (disambiguation).

The Snake River is a river in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. With a length of 1735 km, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, the largest North American river that flows into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake River originates in western Wyoming and then flows through the Snake River Plain in southern Idaho, Hells Canyon on the Oregon-Idaho border, and the Palouse Hills in Washington before joining the Columbia River at the Tri-Cities.

The Snake River basin encompasses parts of the six U.S. states of Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Utah, Nevada, and Wyoming and is known for its diverse geologic history. The Snake River Plain was created by a volcanic hotspot that today lies beneath the headwaters of the Snake River in Yellowstone National Park. Gigantic glacial retreats that occurred during the last Ice Age formed canyons, cliffs, and waterfalls along the middle and lower Snake River. Two of these catastrophic floods, the Missoula Floods and the Bonneville Floods, significantly impacted the river and its surroundings.

Prehistoric Indians lived along the river for more than 11,000 years. Salmon from the Pacific Ocean was a vital resource for the people who lived along the Snake River downstream from Shoshone Falls. When Lewis and Clark explored the area, the Nez Perce as well as the Shoshone were the dominant Native American groups in the region. Later explorers and fur trappers continued to change and utilize the resources of the Snake River Basin. At one point, the sign language used by the Shoshones was misinterpreted, giving the Snake River its present name.

By the mid-19th century, the Oregon Trail had become established and brought numerous settlers to the Snake River region. Steamboats and railroads moved agricultural products and minerals along the river in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Beginning in the 1890s, fifteen large dams were built on the Snake River to generate hydroelectric power, improve navigation, and provide irrigation water. However, these dams blocked salmon migration above Hells Canyon and caused water quality and environmental problems in certain areas of the river. Removal of several dams on the lower Snake River has been proposed to restore some of the river's once formidable salmon migration.

At the headwaters of the river, some 670 km of the Snake River itself and its tributaries in Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks are designated as a National Wild and Scenic River, and a further 107 km downstream of Hells Canyon Dam in Hells Canyon have the same status.

History

From the source through the Rocky Mountains

The Snake River has its source on the southern flank of the Two Oceans Plateau on the continental divide in southern Yellowstone National Park in western Wyoming. Within the national park, it receives the Heart River from the right and initially flows northwest, but then turns south south of Mount Sheridan in the Red Mountains and leaves Yellowstone National Park near its South Entrance. It then flows through the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway into Grand Teton National Park. There it first flows through Jackson Lake, enlarged by Jackson Lake Dam, and then passes through Jackson Hole, a broad valley between the Teton Range and the Gros Ventre Range. Just before leaving the national park, it receives Cottonwood Creek from the right and the Gros Ventre River from the left and continues south past the tourist town of Jackson. Further south, the Snake River turns west, receives the Hoback River and Greys River tributaries, and flows through Snake River Canyon, a break in the Snake River Range. It flows through Palisades Reservoir, where the Salt River joins it from the south through Star Valley. Below Palisades Dam, the Snake River flows through the Snake River Plain, a plain that arcs some 600 km through southern Idaho.

Snake River Plain

Southwest of Rexburg, Idaho, the Snake River receives the Henrys Fork from the north. The Henrys Fork is sometimes called the North Fork of the Snake River, and the Snake River is then called the South Fork before the confluence. From there it turns south, flowing through downtown Idaho Falls, then past the Fort Hall Indian Reservation and into the American Falls Reservoir, where the Portneuf River joins it. From there, the Snake River continues west again and enters Idaho's Snake River Canyon. Several large cascades and waterfalls follow in the river's course, the largest being the 65-meter-high Shoshone Falls, also called the Niagara of the West. Due to their height they form an insurmountable obstacle for fish on their migration to the spawning grounds. A little further downstream, the Snake River Canyon is crossed by the Perrine Bridge. East of Twin Falls the Snake River has reached its southernmost point and flows west-northwest from there on.

Continuing on, the Snake River flows through Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument and receives the Malad River north of Hagerman. It flows past Glenns Ferry, receives the Bruneau River from the south in C. J. Strike Reservoir, crosses an agricultural valley about 20 miles (48 km) southwest of Boise, and makes a short detour into Oregon before turning north to mark the Idaho-Oregon border. Near Ontario, the Snake River nearly doubles in size as it receives several major tributaries - the Owyhee River from the southwest, then Boise River and Payette River from the east, and further downstream Malheur River from the west and Weiser River from the east.

Through Hells Canyon to the mouth

Near the town of Huntington, the Snake River enters Hells Canyon, a steep, spectacular gorge that runs through the Salmon River Mountains and the Blue Mountains of Idaho and Oregon. Hells Canyon is one of the most rugged and treacherous sections of the Snake River and presented a major obstacle to 19th century American explorers. Within the canyon, the Snake River is dammed by Hells Canyon, Oxbow, and Brownlee Dams, which together form the Hells Canyon Hydroelectric Project. The Snake River now flows a long distance through Hells Canyon, which is one of the deepest canyons in the world at 2410 meters deep. Halfway down Hells Canyon, in one of the most remote and inaccessible sections in the Snake River's entire course, its largest tributary, the Salmon River, joins it from the east. From there, the Snake River forms the border between the states of Washington and Idaho, receiving the Grande Ronde River from the west before receiving the Clearwater River from the east at Lewiston. The Snake River is navigable only to the confluence of the Snake River and Clearwater River. The river leaves Hells Canyon, turns west, and meanders through the Palouse Hills in southeastern Washington. The four dams and navigation locks of the Lower Snake River Project have transformed this portion of the Snake River into a series of reservoirs. Near Almota the Snake River reaches its northernmost point, from there it flows southwest again until it finally joins the Columbia River after a total of 1735 km at Burbank east of the Tri-Cities (Pasco, Kennewick and Richland). This flows for about 523 km further west into the Pacific Ocean at Astoria.

·

The Snake River in front of the Teton mountain range

· .jpg)

The Snake River in the Snake River Canyon (Wyoming)

· .jpg)

The Shoshone Falls

·

The Snake River at Hells Canyon Reservoir Dam

_7-09-2014_16-01-04.JPG)

Confluence of the Greys River and Snake River near Alpine, Wyoming

.jpg)

Confluence of Snake River and Clearwater River near Lewiston, Idaho

Geology

165 million years ago, most of western North America was still part of the Pacific Ocean. Near-complete subduction of the Farallon Plate beneath the westward-moving North American Plate created the Rocky Mountains, which were pushed upward by rising magma between the sinking Farallon Plate and the North American Plate. As the North American Plate moved westward across a stationary hotspot beneath the crust, violent lava flows and volcanic eruptions formed the Snake River Plain. This began about 12 million years ago west of the Continental Divide. Even larger lava flows over eastern Washington, consisting of Columbia River basalts, formed the Columbia Plateau southeast of the Columbia River and the Palouse Hills on the lower Snake River. Other volcanic activity formed the northwestern part of the Snake River Plain. This area is far from the path of the hotspot that now lies beneath Yellowstone National Park. At this time, the Snake River drainage basin was beginning to take shape.

The Snake River Plain and a "gap" between the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Range together formed a "moisture channel" that allowed storms from the Pacific to travel more than 1,600 km inland to the headwaters of the Snake River. As the Teton Range rose north-south along a basal thrust plane in the central Rocky Mountains about 9 million years ago, the river maintained its original course, cutting across the southern end of the mountains and forming the Snake River Canyon of Wyoming. About 6 million years ago, the Salmon River Mountains and Blue Mountains formed at the western end of the Snake River Plain, and the river also cut through these mountains and formed Hells Canyon. Lake Idaho, formed during the Miocene, covered much of the Snake River Plain between Twin Falls and Hells Canyon, but its lava dam was breached about 2 million years ago.

Lava flowing from Cedar Butte in what is now southeastern Idaho blocked the Snake River at Eagle Rock, near what is now American Falls Dam, about 42,000 years ago. This created the 64-kilometer-long American Falls Lake. The lake was stable and lasted for nearly 30,000 years. About 14,500 years ago, pluvial Lake Bonneville in what is now the Great Salt Lake area catastrophically flooded down the Portneuf River into the Snake River as part of the Bonneville Flood. This was one of the first of the catastrophic floods known as Ice Age Floods in the Northwest.

The flood caused American Falls Lake to breach its natural lava dam, which quickly eroded, leaving only the 50-foot-high American Falls at the end. The Lake Bonneville flood, about 140,000 m³/s, swept down the Snake River throughout southern Idaho. For miles, the floodwaters destroyed soils, scoured the underlying basaltic rock, and transformed the region into Channeled Scablands that formed the Snake River Canyon. Shoshone Falls, Twin Falls, Crane Falls, Swan Falls, and other waterfalls were formed along the Idaho section of the Snake River. The Bonneville flood continued to follow the course of the Snake River through Hells Canyon, eventually reaching the Columbia River. The flood widened Hells Canyon but did not deepen it.

As the Bonneville floods were rushing down the Snake River, the Missoula floods were occurring further north at the same time. These occurred more than 40 times from 15,000 years ago to 13,000 years ago. They were caused by glacial Lake Missoula on the Clark Fork, which was repeatedly filled in by ice dams and then breached, with the lake's waters causing massive flooding that affected much of eastern Washington. The Missoula floods were far greater than the Bonneville floods. These floods pooled behind the Cascade Range, forming huge lakes and carving deep canyons through the Palouse Hills, including the Palouse River Canyon with Palouse Falls. The Bonneville floods and the Missoula floods helped widen and deepen the Columbia River Gorge, a huge rocky gorge that allows water from the Columbia and Snake rivers to flow directly through the Cascade Range to the Pacific Ocean.

The massive amounts of sediment deposited by the Bonneville floods in the Snake River Plain also had a lasting effect on the middle Snake River. The high hydraulic conductivity of the mostly basaltic rocks in the Plain led to the formation of the Snake River Aquifer, one of the most productive aquifers in North America. Many rivers and streams that flow toward the Snake River from the north side of the Plains sink into the aquifer instead of flowing into the Snake River. These streams are also called the Lost streams of Idaho. The aquifer fills with nearly 120 km³ of water, and in places the water leaves the rivers at rates of up to 17 m³/s. Much of the water that the Snake River loses when it cuts through the Snake River Plain is added back to the river at its western end, for example through artesian wells.

Map of the lost rivers of Idaho. Here it is visible that the rivers coming from the north do not flow directly into the Snake River, but seep into the aquifer.

Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls, Idaho

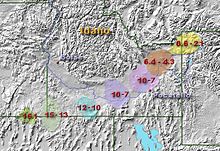

Yellowstone hotspot locations as you cross the Snake River Plain.

Search within the encyclopedia