Sleep disorder

![]()

This article describes the insufficient restfulness of sleep in humans. For less common uses of this colloquial term, see also dyssomnia.

The term sleep disorder (syn. agrypnia, insomnia and hyposomnia) refers to variously caused impairments of sleep. Causes can be external factors (such as noise at night, excessively bright street lighting), behavioural factors (e.g. problematic sleep hygiene) or biological factors.

The lack of restful sleep impairs performance in the short term and can also lead to the worsening or recurrence of diseases in the medium or long term. Sleep disturbances reach the level of a disease if they are the cause of physical or mental impairments and are also subjectively perceived as pathological by those affected. Also the opposite sleep behavior, the sleep addiction (technical term Hypersomnie), can be the consequence. However, in the German-language literature, this is not summarized under the term sleep disorder.

A special form of sleep disorders are the parasomnias: This is atypical behavior during sleep (with disturbance of the same), but the affected person does not wake up. Complete insomnia that cannot be treated (as in lethal familial insomnia) is fatal. However, this is an extremely rare form of a prion disease (< 1/1 million), which is characterized less by the sleep disorder itself than by a generally reduced level of vigilance (= wakefulness) during the day as well as pronounced impairment of mental abilities even when awake, which extends far beyond the complaints in the context of the otherwise very common sleep disturbances. In contrast to non-organic insomnia, which is accompanied by an inability to fall asleep during the day, lethal familial insomnia is primarily characterized by an increased permanent tendency to fall asleep/drowsiness/somnolence (in contrast to the inability to fall asleep/drowsiness during the day present in most insomnia patients). Pathologically increased daytime sleepiness (e.g. assessable by the so-called Epworth Sleepiness Scale) is in most cases caused by a treatable biological disorder of sleep quality. These include, above all, sleep-related respiratory and movement disorders.

In order to differentiate between the individual subtypes of sleep disorders, it is particularly important to take a careful medical history and, of course, usually also to carry out further examinations, for example in a sleep laboratory. Treatment is essentially based on the causes. If, for example, the sleep disorder is the result of an internal disease, its treatment is a priority. If, however, it is triggered by a wrong handling of sleep, a corresponding education of the patient and - if necessary - also a behavioural therapy are indicated.

Appearances

Clinical manifestations

The leading symptom of sleep disorders is the lack of restful sleep. Delayed falling asleep, disturbed sleeping through and early awakening are subsumed under this term. In the case of unpleasant sleep, a more or less intensive sleepiness can also occur during the day, in the context of which alertness and the ability to sustained attention (vigilance) are reduced. In addition, the affected person may also be exposed to a not always equally strong urge to fall asleep during the day. Other typical symptoms are irritability, restlessness, anxiety and other symptoms generally associated with fatigue, ranging from a drop in performance to a change in character. In severe cases, these symptoms in particular can also impair the patient's social and professional situation.

The symptoms must occur for at least one month on three days of a week to be considered a disease. If sleep is not restful, performance and well-being are impaired during the day and they are described as severe. Specifically, a healthy person should fall asleep at least 30 minutes after going to bed, should not be awake earlier than 30 minutes after falling asleep (up to 2 hours for older persons) and should not wake up before 5:00 a.m. (without being able to fall asleep again).

Idiopathic, learned and sometimes pseudo-insomnia show very similar clinical symptoms, which is why it is often difficult to distinguish between the two.

An unsolved problem is the discrepancy between the subjective perception of sleep quality and the objective results of polysomnography (PSG). In contrast to healthy sleepers, people with sleep disorders perceive the waking phases to be longer than the apparative measurement of PSG revealed. This led to the term paradoxical imsomnia. More detailed analyses revealed that people with insomnia perceived awakening from REM sleep (usually associated with dreaming) as a long waking period, but not awakening from an N2 sleep phase.

Typical of breathing disorders during sleep (sleep apnoea syndrome) are additionally nocturnal cardiac arrhythmia, high blood pressure, obesity, loud and irregular snoring with pauses in breathing, restless sleep as well as impaired libido and potency.

In pseudo-insomnia, the clinical findings such as reduced performance do not correlate with the sleep disturbance experienced by the patient. However, those affected suffer increased anxiety, particularly about their own health, and depression. In addition, they have an increased risk of abusing medications or other substances.

Schenck's syndrome, which occurs almost exclusively in men, harbours a considerable potential for danger. If, for example, the bed partner is mistaken for an attacker, the latter can be injured in the process and, statistically speaking, stranger endangerment occurs in about two-thirds of cases and self-harm in about one-third of cases - in 7% even bone fractures occur.

Disturbances of deep sleep (they are detected by a lack of delta waves in the electroencephalogram) are considered to be the cause of hypertension, especially in older men.

Sleep deprivation is also considered a risk factor for the development of obesity in adults and children (see: Obesity#Sleep habits).

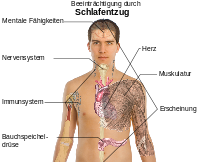

Consequences of sleep deprivation

Many studies exist on the psychological and physical effects of sleep deprivation. In one major study by the American Cancer Society, over one million participants were asked only about their average sleep duration. It showed that participants who slept less than 6 hours and more than 9 hours per night had a higher mortality rate than expected for their age. Other studies have been able to document the psychological and physical consequences of sleep deprivation in more detail: Sleepiness, concentration and attention deficits, irritability, anxiety, depression, mood swings, lack of self-esteem, impulsivity, and impairment of social relationships. Well-studied physical consequences of sleep deprivation include obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, and higher levels of diabetes, hypertension, heart attack, and stroke.

Distribution

Most people's expectation of good, restful sleep is simple: they want to fall asleep quickly, sleep well through the night and wake up "full of vigour" in the morning. More or less pronounced sleep disturbances are a common phenomenon, subjectively perceived and judged by the patient. Even those who do not wake up well rested every morning may in some cases perceive this as a sleep disturbance. The frequency of occurrence in the population ultimately depends on how one defines sleep disturbance. It ranges from just under 4% to about 35%. The question at what point a disturbed sleep is to be described as a pathological sleep disorder from a medical point of view can therefore not be answered in a generally valid way. In practice, however, it can be assumed that about 20 to 30 % of all people in western industrial countries have more or less pronounced sleep disorders. In about 15% of these cases there is also fatigue during the day and a general restriction of performance, so that treatment is indicated here. About 2% of all adolescents and young adults have significant sleep disorders due to poor sleep habits alone. Objectifiable disturbances of the sleep-wake rhythm are rare. A too late time for falling asleep, the so-called delayed sleep phase syndrome, is found in about 0.1 % of the population, a too early (advanced sleep phase syndrome) in about 1 %.

Typically, older people wake up several times during the night and have a lighter sleep overall (lower wake threshold). However, these changes alone are not perceived as pathological by the vast majority of those affected. The main influencing factors are simultaneously existing health impairments as well as the influences of the environment and social situation. Abnormalities during sleep (parasomnias) occur more frequently in childhood. A parasomnia that characteristically only occurs after the age of 60 (almost 90 %) is the relatively rare (0.5 % of the population) Schenk syndrome in men (almost 90 %). 100% of all people experience a nightmare at some time, and about 5% of all adults develop significant distress due to nightmares. About 1 to 4% suffer from sleepwalking, sleep disturbances caused by eating or drinking at night, or night terrors. About one in three sleep disorders, an estimated 3% of the total population, is caused by a psychiatric disorder, such as depression.

Acute, short-term sleep disturbance triggered by stress is estimated to affect almost 20% of all people each year and can occur in all age groups, but is most common in older people and women. Psychophysiological (learned) sleep disorders affect about 1-2 % of the population. Quite rare (about 5 % of all sleep-disordered persons) is also the so-called pseudo-insomnia, in which the affected persons only have the feeling of sleeping badly, but this cannot be objectified.

Idiopathic, or lifelong, insomnia without a known cause affects less than 1% of all children and young adults. Congenital fatal familial insomnia occurs in less than 1 in 1 million people.

Sleep disorders in children

Overview

Basically, children can experience essentially the same types of sleep disorders as adults. However, parasomnias account for a larger proportion in this age group. This includes apnea of prematurity, a condition that is attributed to the immaturity of the respiratory center in the brainstem. Although it primarily affects underweight premature infants (occurring in about 85% of all under 1000 g), it also plays a role in everyday life. For example, it can be assumed that about 2% of all infants born on time and healthy will experience at least one episode of at least 30 seconds of respiratory arrest and at least 20 seconds of a drop in heart rate to below 60 beats per minute in the first six months of life. Other parasomnias typical of infancy include obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and primary alveolar hypoventilation syndrome. Another phenomenon unique to children is benign sleep myoclonus.

Sleepwalking and Pavor nocturnus

Due to its frequent occurrence in children, sleepwalking or nightwalking, which also belongs to the group of parasomnias, occupies a prominent position. Almost one third of all children between 4 and 6 years and about 17 % of all children up to puberty are affected. The child may sit up, look around, talk, call or write and even in some cases jump out of bed and walk around. Of course, since he is still deeply asleep during this, he may be difficult to wake up, react in a disorderly aggressive manner afterwards, and not remember the incident. Many children (over 17%) are affected by the Pavor nocturnus, also known as sleep or night terrors, before the age of 11. This disorder, which usually lasts only a few minutes, cannot be strictly distinguished from sleepwalking in all cases and is characterized by a partial awakening from deep sleep, typically beginning with a cry. This may also involve children jumping out of bed. Characteristic of night terrors is intense anxiety experienced by the child, accompanied by activation of the autonomic nervous system with accelerated heartbeat and equally accelerated breathing, as well as reddening of the skin. In both forms of sleep disorder, factors such as lack of sleep, stress and fever are considered triggers. Both occur in families and usually disappear in adulthood.

problems falling asleep and staying asleep

In the case of behavioural insomnia in childhood (in technical jargon: protodyssomnia), falling asleep and sleeping through are also the main symptoms. Two main groups can be distinguished. The sleep onset association type, for example, needs certain objects and rituals to find sleep. In the case of the limit-setting type, an excessively generous upbringing leads to an attitude of refusal on the part of the child, which ultimately also culminates in sleep disorders. Two doctrines now dominate the professional and counseling literature regarding behavioral insomnia: Some research-oriented authors, including, for example, Richard Ferber, attribute the insomnia of many children to their parenting-induced inability to self-soothe and recommend that parents of such children gently but consistently train the ability to find sleep on their own so that the child can become independent of the often excessive parental micromanagement of childhood sleepiness. Others, however, especially Attachment Parenting adherents such as William Sears, consider insomnia to be anxiety-related and recommend co-sleeping.

(→ Main articles Sleep training, Childhood emotional disorders, Excessive crying in infancy, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and Social behavior disorder).

Clinical symptoms due to sleep disorders in children are very similar to those of adults. In addition, however, not only the child but also the parents suffer considerably. Thus, negative, aggressive emotions towards the child may arise, or even the parental partnership may be threatened.

Structural anatomical changes

In chronic insomnia, structural anatomical changes in the brain could be detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Specifically, this involves a reduction in the size of the hippocampus. Even if this does not apply to all forms of primary sleep disorders, this fact could be reproduced in two independent studies, at least for patients with increased nocturnal movement activity.

In hereditary fatal familial insomnia, a spongy change of the brain is found. Particularly striking are gliosis and loss of nerve cells, especially in the area of the anterior and dorsomedial thalamic nuclei.

The symptoms of non-restorative sleep correspond in essential aspects to those of sleep deprivation

Cause

→ for sleep architecture in normal subjects, see the corresponding section in the main article Sleep.

Different causes leading to a sleep disorder cause that the sleep is not restful. Changes in the duration or course of sleep are responsible for this. There are no concrete parameters for measuring when sleep is no longer restful. Regarding the duration of sleep, the German Society for Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine formulates in the AWMF guideline: "There is no binding time standard for the amount of sleep that is necessary to ensure restfulness. Most people know the amount of sleep from their own experience." Similarly, there are no concrete, generally applicable standards for the course of sleep, for example, when, how often and how long the individual sleep phases must be present so that a night's sleep is refreshing.

Sleep disorders for which no cause can be found are also called primary or idiopathic. Secondary are called those in which reasons are comprehensible that the sleep is disturbed in duration and sequence. A special form is parasomnia.

In addition, extrinsic and intrinsic disorders can be distinguished. The former include all causes that originate outside the patient's body, such as alcohol, lack of sleep or environmental influences such as light pollution. Mobile phone radiation may also be one of them. Impairments of the circadian sleep rhythm such as jet lag (time zone change) and sleep phase syndrome (advanced or delayed) are also usually included. Primary insomnia, sleep apnoea syndrome and restless legs syndrome, for example, are described as intrinsic.

Another special feature is pseudo-insomnia. In this misperception of the sleep state, night sleep in the sleep laboratory is completely regular and normal, but the affected persons have the feeling upon awakening that they have not slept or have slept poorly.

Sleep disorders in depression and anxiety disorders

There is a scientifically established link between sleep disorders - especially insomnia - and depression. Often insomnia is found in patients diagnosed with clinical depression, where this is considered a core symptom. Anxiety disorders can also be accompanied by insomnia. Vice versa, people with insomnia are more likely to develop depressive disorders and anxiety disorders.

People with depression are slower to respond to sleep disorder treatment than other patients with sleep disorders.

Disease development

→ For the "Hypotheses on the function of sleep", see also the section of the same name in the main article Sleep.

Ultimately, the decisive question is what is restorative about one sleep and what prevents the other from being so. To be restorative, it must in any case be sufficiently long and have as undisturbed a course as possible. In particular, the deep sleep phases must also be present to a sufficient degree. In depressive patients, for example, they are significantly reduced. Those affected wake up more often at night than healthy people, REM sleep not only occurs more frequently and earlier, but is also accompanied by particularly intensive eye movements. 90% of all depressives do not have restful sleep. Fatal familial insomnia is further characterized by an increasing loss of K-complexes and delta waves. REM sleep may also be altered in her.

In learned insomnia, a disturbed sleep pattern (delayed falling asleep, more light sleep and less deep sleep), increased release of cortisol and interleukin-6, alteration of anatomical structures in the brain, and a normal or increased tendency to fall asleep during the day were found.

Idiopathic insomnia is characterized - in some cases already in childhood - by a prolonged period of time until falling asleep, increased lying awake at night and consequently a shortening of the total sleep time. In addition, the deep sleep phases (stages III and IV) are significantly reduced compared to light sleep (stages I and II).

Schenk syndrome, which usually occurs only in advanced adulthood, is characterized by an intense acting out of dream content about attacks, defense and flight. In the sleep laboratory, an increased tone of the chin muscle is found, not infrequently accompanied by arm or leg movements. Nightmares typically lead to immediate awakening, accompanied by vegetative symptoms such as rapid heartbeat, accelerated breathing and excessive sweating. Both of these abnormalities are found primarily in the second half of the night. Sleep disturbance caused by eating or drinking at night also leads to increased waking from NREM sleep. Disturbances in falling asleep or sleeping through the night also occur in the case of nocturnal heartburn in the context of reflux disease. In restless legs syndrome, the constant involuntary movements also severely disturb the architecture of sleep.

In central sleep apnea with Cheyne-Stokes breathing, a subtype of sleep apnea syndrome, the breathing disorder occurs particularly during light sleep (stages I and II), but is significantly reduced or completely absent in the deep sleep phases (stages III and IV) and in REM sleep. Due to an undersupply of oxygen to the body, it leads to frequent awakenings. Sleep becomes fragmented, with deep sleep phases also becoming less frequent and sleep losing its restfulness. In another subtype, central sleep apnea in altitude-induced periodic breathing (occurs above 4000 m), a reduction of deep sleep in favor of light sleep is also found. Similar results are also found in other clinical pictures from the group of forms of sleep apnoea.

In the case of time shifts, such as those that occur during shift work or air travel, the light-dark rhythm of the times of day, the circadian rhythm of numerous bodily functions and the "clock genes" innate in humans as day-active creatures influence the course of sleep (→ see also jet lag). In this case, deep sleep also decreases in duration and severity. The similar but chronic changes in the time it takes to fall asleep are thought to be caused by predisposition, long-term disturbances of the light-dark rhythm, inadequate sleep hygiene and compensation for insufficient sleep on previous days.

Unlike the other forms of sleep disorders, pseudo-insomnia lacks objectifiable findings in the sleep laboratory. Those affected nevertheless perceive their sleep as not restful.

Primary and secondary insomnia

→ Main article: Primary insomnia

Primary insomnia is defined by the fact that no specific causes are found.

Causes of secondary, i.e. acquired, insomnia are, for example, diseases or substances that have a correspondingly negative influence on sleep phases. This is quite easy to understand in the case of diseases such as benign enlargement of the prostate gland or heart failure, which can lead to frequent urination at night. As a result, night sleep is interrupted several times and loses its restfulness.

This is similarly easy to understand in the case of short-term changes in the internal clock and thus in the sleep-wake rhythm, whereby - expressed colloquially - the night sleep becomes the midday sleep and thus has a different sequence (for example, fewer deep sleep phases). Analogous changes are also seen in shift work, when the actual sleeping time becomes working time. It is less common, but similar, in people who have normal sleep, but whose internal clock, for unexplained reasons, is lagging behind or ahead in the long term (chronic sleep-wake rhythm disturbance), i.e. who, for example, can only fall asleep between one and six o'clock in the morning and would then have to sleep until noon in order to achieve a sufficient amount of sleep for recovery. Preferably in blind people, in whom the change of light and dark as a clock of the inner clock is also missing due to the lack of vision. But even in normally sighted persons, a shift in the time of falling asleep of one to two hours daily to the rear can occur (free-running rhythm). Each of the three forms of chronic sleep-wake rhythm disorders can be caused in the same way by diseases such as fibromyalgia, dementia, personality and obsessive-compulsive disorders, or by taking medications such as haloperidol and fluvoxamine or drugs.

Depression is associated with sleep disturbances in the vast majority of patients. A relative predominance of the cholinergic system and a deficient function of REM sleep are considered to be causal factors.

Stress can severely affect nighttime sleep. The stress can be caused by disruptions in the social environment or at work (this includes longer-term factors, but also short-term ones such as on-call or emergency doctor duty), but also by moving house, changes in the environment while sleeping, or the occurrence of serious physical illnesses, as well as, in a broader sense, after previous excessive physical exertion (→ main article Overtraining). Because of the stressor, these patients often ruminate during the day and are affected by anxiety, sadness, and dejection. The complaints usually end when the circumstances have little or no significance for the person in question, which is why this form is also referred to as adaptation-related, transient, passive or acute insomnia. This stress-related form is considered a common cause of insomnia referred to as learned, chronic, conditioned, primary, or psychopathological, in which sufferers internalize, i.e., learn, associations that interfere with sleep or lead to awakening to such an extent that restful sleep is no longer possible. A simple example is a hospital or emergency doctor who has internalized over decades through weeks of on-call duty to suddenly and abruptly "function" optimally and flawlessly when alerted, and who thus does not find restful sleep even outside of his duty hours. In the long term, this learned insomnia also leads to irritability, impaired mood, performance, concentration, motivation and attention. Typically, these patients also do not nap during the day.

A "strong" or "very strong" induction of sleep disorders is described by the German Society for Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine in the corresponding AWMF guideline for substances such as alcohol, caffeine, cocaine, amphetamines (including ecstasy, crystal) and methylphenidate.

Other causes are in particular internal, neurological and psychiatric clinical pictures such as varicose veins, hyperthyroidism, reflux disease, pain syndromes, psychoses, epilepsy, dementia and Parkinson's disease, which can affect sleep.

Fatal familial insomnia is genetic.

Parasomnia

→ Main article: Parasomnia

These are phenomena that occur during sleep. They include, for example, nightmares, bed-wetting, sleepwalking, sleep drunkenness, sleep paralysis, uncontrolled movements during sleep such as restless legs syndrome or paroxysmal dystonia, teeth grinding during sleep and also night terrors. While these abnormalities do not affect the restfulness of sleep per se, unpleasant sleep is often associated with them nonetheless. The symptoms can occur either during or outside of REM sleep and also independently of it. Sleepwalking, night terrors and sleep drunkenness belong to the group of parasomnias as so-called waking disorders, as do disorders of the transition from sleep to wakefulness such as talking during sleep, calf cramps and twitching to fall asleep or rhythmic movements during sleep. Triggers for sleepwalking include external factors such as loud noises, as well as fever, pain, and various medications and alcohol. A hereditary change on chromosome 20 (gene locus 20q12-q13.12) has also been identified. Not only factors such as neuroticism, post-traumatic stress disorder and stress are considered to be the cause of nightmares, but also changes in the genetic make-up, which are not yet known in detail. Similar to sleepwalking, sleep disturbances caused by nocturnal eating or drinking, as is often the case with withdrawal or strict fasting, lead to insufficient sleep for those affected.

The type of symptom that occurs does not affect sleep in the same way in all cases. For example, sleep may not be perceived as restful due to a nightmare, because the person woke up from an emotionally negative dream, fear of the recurrence of such an event, or even a disturbance in breathing occurred during the dream.

In Schenk syndrome, about half of the cases have no apparent cause and the other half are due to so-called synucleinopathies.

If, due to a change in the state of tension of the musculature in the upper airways or due to a disturbance of the central respiratory regulation, there are impairments (hypopneas) or a more or less prolonged cessation of breathing during sleep, this leads to the body being temporarily supplied with too little oxygen. It is not uncommon to find increased carbon dioxide or a reduced pH value in the blood. If these impairments occur too frequently, the sequence of sleep phases also changes and sleep loses its restfulness. This is called sleep apnea syndrome. The same changes can also occur in the context of an underlying disease (e.g. heart failure) and are then classified as "secondary sleep disorders" (→ main article Sleep apnoea syndrome).

Nightmares and night terrors, as artistically depicted here by Füssli, are among the intrinsic sleep disorders

Even in stressful situations (here an excerpt from a war diary) sleep is often not restful.

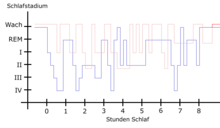

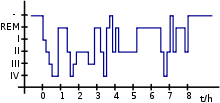

In the case of restless legs syndrome (shown in red), constant nocturnal movements mean that, compared to healthy sleep (shown in blue), the deep sleep stages III and IV are not reached, or are reached only very rarely, and those affected wake up significantly more often.

The normal sleep stages of a night. It can be clearly seen that during a normal course of events, both the deepest sleep phase (IV) and the waking state (-) are reached several times.

Search within the encyclopedia