History of slavery

The history of slavery covers the development of the treatment of human beings as the property or commodity of other human beings, slavery, from early history to the present. It begins, insofar as it is documented in the form of legal texts, contracts of sale and the like, in the earliest advanced civilizations of mankind, that is, in Mesopotamia, where it was enshrined, among other places, in the Babylonian Codex Ḫammurapi (18th century BC). Slavery also existed in Egypt and Palestine and is particularly well documented in Greece (Slavery in Ancient Greece) and Rome. The treatment of slaves and slave women was also regulated in detail in the Old Testament (e.g. Leviticus 25:44-46). In 492, Pope Gelasius I declared that the trade in pagan slaves was also permitted to Jews.

In the early European Middle Ages, Khazars, Varangians and Vikings, among others, traded with slaves, especially Baltic slaves. For the period between the 10th and the 12th century, there is evidence of trade in Slavic slaves for the Saxons from the East Francia. After the increasing missionization of the Slavic tribes and the triumphant advance of Christianity, whose teachings forbade Christians to buy or sell other Christians, slavery disappeared from Central Europe, but gained all the more importance south of the Alps, for example in the Italian maritime republics, in the Black Sea region, in the Balkans and in the Near East, especially in Egypt. For in the Mediterranean region new opportunities arose with the expansion of trade relations, which also encouraged robbery and piracy. Thus, for example, the conflicts between Christian and Islamic societies and the resulting mutual captives or abductees offered a constant source of new slaves for the respective markets.

Slavery became even more widespread in modern times with the expansion of European maritime trade and the founding of European colonies, especially on the American double continent. This was so sparsely populated and offered the colonists so little suitable native labour that millions of African slaves were imported to build the plantation economies on which the profitability of these colonies was to be based for centuries.

While slavery is best documented in European cultures, it traditionally existed in many non-European cultures as well, such as among North American Indians and in West Africa. It is also well established for Arab-Muslim societies that they maintained various forms of enslavement for fourteen centuries up to the present, despite the promises of salvation contained in the Qur'an that were linked to the manumission of slaves.

From the late 18th century onwards, the slave trade and slavery were gradually abolished by law worldwide. International agreements against slavery were concluded in 1926 and 1956, among others. Mauritania was the last country in the world to abolish its slavery laws in 1980, although slavery still exists in Mauritania.

Middle Ages

Slavery experienced an upswing between the 8th and 10th centuries. Even before the Scandinavians invaded the Baltic region, Turkic peoples such as the Khazars conducted a lively trade in light-skinned slaves from Europe. After the Varangians or Rus had invaded the Eastern European area and established themselves, they took over this trade from the Khazars, with whom they sometimes maintained intensive trade relations and sometimes were in strong competition. Subsequently the Norse warrior merchants also carried on a flourishing trade in prisoners of war. The Normans haunted all the coasts of the North Sea, and about the year 1000 sold Irish or Flemish captives in the market of Rouen, from whence they passed into Christian households, but chiefly into Muslim Spain and the Orient, as the destination of the main streams of the slave trade. In the Islamic countries, the light-skinned European slaves were called Saqaliba.

During the warlike conflicts with the Slavs under Henry I (928/29), women and children in particular were sold as important "trade goods" from the Ottonian Empire to Muslim Spain. In Prague and Verdun there were centres set up specifically for castration, in which Slavic boys were made into eunuchs, which were particularly sought after by the Muslims. Until the 12th century, "slave hunts" took place, in which the Saxons raided the neighbouring Slavs, plundered them and carried them off into slavery.

The West Slavic tribes between the Elbe and the Baltic Sea (see Wends) also came under pressure from the Danish and East European side (Kievan Rus). Adam von Bremen reports that Slavic slaves were offered as sacrifices in Estonia. According to Ibn Fadlān, deceased Rus were given young female slaves or slaves to take with them to the afterlife; however, they came to Baghdad mainly as trade goods with caravans. The trade in slaves was taken over by the Radhanites, Jewish merchants from Baghdad, and others. They enjoyed royal privileges in Europe and, because of their ramified family connections, were the only ones to extend trade from Spain through North Africa, Egypt, the Arabian Peninsula, Palestine, Syria, Persia, northern India, Khorasan, to China and, via Byzantium, to the Slavic lands and the Jewish Khazars on the Black Sea. Based on the findings presented by Charles Verlinden and the French historian Maurice Lombard and a work by the Russian Orientalist Dimitri Michine published in 2002, the French historian Alexandre Skirda concludes that the economic boom of the Occident in the 10th and 11th centuries was due to the trade in human beings with the Islamic countries, from which large quantities of gold came to the West in exchange. As late as 1168, 700 Danes were offered for sale by pirating Slavs at the slave market in Mecklenburg.

In Anglo-Saxon and Norman England of the 11th century, too, slaves (servi, ancillae; thraells in the Danelaw) lived alongside unfree peasants (villani). In 1086, according to the Domesday Book, there were 28,200 slaves there. However, not all slaves seem to have been accounted for; the number was probably much higher. In some counties the servi formed up to 25% of the population. Monasteries (such as Ely Abbey) also used slaves in agriculture; according to the Domesday Book, 112 unfree peasants, 27 smallholders (bordarii), one priest and 16 slaves lived on the abbey's estates.

In the late Middle Ages, the Baltic or northern European slave trade declined again. Most European peoples had become Christianized by then, and since the time of Charlemagne it had been expressly forbidden for Christians to sell or acquire other Christians as slaves. However, this regulation was often flouted - even popes and monasteries had slaves. Especially in the Eastern Mediterranean, the prohibition was often circumvented by the argument that it applied only to Roman Catholics, not to Orthodox or members of other Christian churches. Thus, although slavery had all but disappeared north of the Alps in the High Middle Ages, there continued to be lively human trafficking in the Mediterranean region, in which the Italian maritime republics and Catalan sailors in particular took part on the Christian side. Until the 15th century, cities such as Genoa and Venice still traded extensively in slaves from the Black Sea region and the Balkans. The male slaves were mostly sold to the Egyptian Mamluk rulers, more rarely in Italy or Western Europe; women were brought from the countries around the Black Sea to all Italian cities of the Renaissance, thus also to the so-called merchant republics, as well as to Spain, where they were mainly used in the household and often as wet nurses. The importance of this east-west trade route only diminished when, with the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453 and of the entire Black Sea region by the end of the century, long-distance sea trade from this region became almost impossible for western (Christian) merchants and only the land routes through Asia Minor were still viable.

In the sphere of power of the Crown of Aragon, too, slavery and the slave trade were the order of the day, as a large number of archival documents attest. In addition, however, there was an extensive business based on the ransoming of slaves in exchanges between the Iberian east coast, the Balearic Islands and the opposite North African coast - people from both sides who had been enslaved as prisoners of war or as booty from raids by corsairs with the aim of making the quickest and highest possible profit from them. With the expansion of Atlantic shipping from the mid-15th century onwards, the number of black African slaves also increased, which was then to explode with the settlement of the New World.

While the Muslim rulers in Egypt needed slaves mainly for their army (Mamluks - therefore male slaves were most in demand there and a constant supply was needed, as these military slaves usually did not found families), slaves in Italy and on the Iberian Peninsula mostly worked in the household (hence the high proportion of female slaves there). It was also not uncommon for slaves to be used in agriculture by Italians and Catalans in southern Italy and on the Mediterranean islands (for example, Cyprus and Majorca, less frequently Sicily and Crete).

In Western Europe, imported slaves rarely remained slaves until the end of their lives: manumissions or manumissions were relatively common, but often conditional on the slaves thus "freed" continuing to work for their former masters for a certain period of time.

Slavery in the Arab world

→ Main article: Slavery in Islam

Even in pre-Islamic times, the later Islamicized areas knew slavery and slave trade, both with black African and with European slaves. The character of slavery, however, was different from that in antiquity or later in the "new world", apart from the black slaves called Zanj in southern Iraq.

Slavery is not forbidden according to the normative scriptures (Qur'an and Sunna) of Islam, although it should be emphasized that the Qur'an often recommends freeing slaves. The founder of the religion, Muhammad, was himself a slave owner (see Maria al-Qibtiyya) and was documented to have enslaved hundreds of people on his war campaigns, such as all the women and children of the Banu Quraiza. Slavery, however, was subject to certain established rules describing the behavior of the slave owner toward the slave and vice versa. These rules meant a certain upgrading of the legal status of slaves compared to the pre-Islamic period. In religious terms, if slaves were Muslims, they were considered equal to free Muslims before God. Although the manumission of slaves was considered salutary, areas within the scope of Islam delayed the legal abolition of slavery for some of the longest periods of time. Mauritania was the last country in the world to abolish slavery in 1980, but slaves still represent the most secretive lowest social class. Thus, since the seventh century, a tradition has continued, the clearest traces of which led to the end of the 19th century with caravans through the Sahara to various Arab cities on the Mediterranean or to the ports of East Africa on the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Often slaves were used in entertainment (mostly female slaves who lived with the women in the harem), as personal servants of the rulers or as harem guards / servants (mostly as eunuchs). A certain group of male slaves were prevented from reproducing by castration. The main purpose of this was to moderate the sexual drive so that the male slaves, who were employed in the harem and had daily intercourse with the harem women, would not be tempted to engage in illicit sexual acts. Female slaves, on the other hand, were called upon to perform sexual services and could also have children by their masters, which under certain circumstances could decisively improve their legal status (see also concubinage in Islam).

Since in the pre-Islamic cultures of the Orient descent through the male line had priority and this was still true after the Islamization of these areas, the children of female slaves could attain the highest positions depending on the position of the child's father. Thus, almost all later caliphs were sons of female slaves. Even the founder of the Saud dynasty, Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud, the father of the present Saudi king, therefore did not know who his mother's mother was (namely, an unknown slave). Wealthy, influential people of the pre-Islamic period often had 50 sons by many women of different origins, which was still found among Islamized peoples. For example, the so-called "Lawrence of Arabia" tells of a bath in an oasis pond after a long desert ride, where young, closely related men of every conceivable shade of skin splashed about naked and chipper and equal in the water. Slaves could also attain high political and military office, but remained the personal property of their owners.

With the military slaves (the so-called Mamluks), a special form of slavery developed in the late 11th century. These slaves, who were used as soldiers in Egypt, were held in high esteem because of their loyalty and bravery. At times they even succeeded in seizing political power, as they did in Egypt from the middle of the 12th century until 1517. The first Ottoman Janissaries were also recruited as slaves.

From Greece to Italy to Spain, Arabs and Turks robbed Christian and Jewish slaves for centuries, selling them at slave markets or returning them for ransom. However, European slaves, especially from the Slavic territories, the Balkans, and the Caucasus regions, were not only robbed by non-Christian traders, but for centuries were also sold to Egypt by the merchants of the Italian maritime republics, especially Genoa and Venice, as well as by Catalans, so that repeated popes attempted to prohibit the trade in Christian slaves, such as Clement V and Martin V (cf. Davidson, p. 34). At the time of the Crusades and Ottoman expansion, it was precisely the periodic oversupply of enslaved prisoners of war that posed a problem. Conversely, parts of the Arab-Muslim population of North Africa and the eastern Black Sea region also fell victim to the raids of Christian merchants and corsairs. Particularly in the western part of the Mediterranean, where between the Iberian Peninsula, the Balearic Islands, Sicily and Malta the Islamic and Christian spheres of influence directly touched, and in some cases even overlapped, there were regular enslavements from the 14th century onwards, which, however, generally served to obtain ransoms and were thus very limited in time (see above).

Slavery and human trafficking developed into a real economic sector in the Islamic barbarian states on the coast of North Africa between the 16th and 18th centuries. Although they came under Ottoman suzerainty in the course of the 16th century, the territories ruled by local Arab princes enjoyed extensive autonomy until the 19th century. This was also the case in Algiers, which became a stronghold of piracy directed against European ships and cities from the 1520s onwards under the rule of the notorious corsair Chair ad-Din Barbarossa. Modern estimates suggest that some 1.25 million people were enslaved in the territories lying between Egypt and Morocco between 1530 and 1780, most of them through the capture of European ships and raids on the coasts of Christian Mediterranean states. The number corresponds to about one tenth of the transatlantic slave trade.

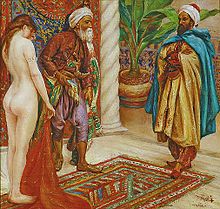

The Newcomer (Giulio Rosati)

Bilal al-Habashi, one of the first Muslims, was a slave

Questions and Answers

Q: What is slavery?

A: Slavery is a condition in which people are owned or completely controlled by other people.

Q: How long has the slave trade been around?

A: The slave trade has been around since some of the oldest civilizations.

Q: What is human trafficking?

A: Human trafficking is a modern form of the slave trade.

Q: Are there different forms of slavery throughout history?

A: Yes, there have been many different forms of human exploitation across many cultures throughout history.

Q: Is buying and selling slaves still happening today?

A: Unfortunately, yes, buying and selling slaves is still happening today in the form of human trafficking.

Q: Who owns slaves in a traditional sense?

A: In a traditional sense, other people own slaves.

Search within the encyclopedia