Slate

![]()

Schiefergruben is a redirect to this article. See also: Nuttlar slate quarries nature reserve.

![]()

This article is about slate as a rock. For articles on other meanings of this word, see Slate (disambiguation).

Slate (ahd. scivaro; mhd. schiver(e) 'stone splinter', 'wood splinter'; mnd. schiver 'slate', 'shingle') is a collective term for different tectonically deformed (folded) and partly also metamorphic sedimentary rocks. Their common feature is excellent cleavage along closely spaced parallel planes, so-called schistosity planes, which are secondary to deformation. However, undeformed, usually fine-grained sedimentary rocks that exhibit such cleavage are also traditionally referred to as "shales". However, these rocks split along their primary bedding planes. From this more inclusive traditional term are derived, for example, the terms oil shale or shale gas, which in a strictly petrographic sense refer to a carbon-rich mudstone or the natural gas still trapped in its parent rock (usually such a carbon-rich mudstone).

In modern petrography, "shale" is only used for tectonically stressed rocks. However, the traditional name has persisted in scientific literature to this day, mostly in the form of lithostratigraphic names, such as Posidonia Shale or Copper Shale.

View of layered surfaces of a Jurassic black mudstone, the so-called Posidonienschiefer, with imprints of fossil shells. Found at Holzmaden (width of the handpiece about 11 cm).

Upstanding Lower Devonian clay schist in the northern Eifel. Weathering makes the thin-layered cleavage clearly visible.

Upstanding Proterozoic mica schist with granitic sigmoid clast (center of image), southern Black Hills, South Dakota, USA.

Clay slate as building stone (roof and facade slate)

Dark clay slate is traditionally used to cover roofs and to clad gables and facades. On the Moselle, in the Hunsrück and in the Eifel, the building of houses with hewn, compact quarry stones made of slate was and is now also common again.

From the Middle Ages until the middle of the 20th century, slates and styluses were made from clay slate. Until the introduction of large-scale industrial paper production and the concomitant fall in the price of writing paper, slates and styluses were a widely used writing material for everyday use, indispensable in trade, in private households, but especially in the elementary school education sector, which had been increasing since the 17th century. From the end of the 19th century until the cessation of industrial stylus slate production in the 1960s, the Thuringian town of Steinach held the world monopoly.

Mining technology

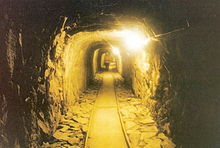

Today's mining is determined by the use of modern equipment and machinery. The fully mechanized, sawing extraction not only facilitates the work of the miners, but also contributes to a careful handling of the valuable rock.

The mineable slate is sawn into grids with a diamond saw along the geological conditions. Block by block, the slate is then released from the mountain. Wheel loaders are used to load the slate underground. The slate is then transported on trolleys by the mine railway to the winding shaft and from there to the production halls above ground. Here the slate blocks are sawn, split and trimmed.

In the surface production, a diamond saw initially takes over the first processing. It ensures that the blocks of different sizes can be used for the production of the capstones largely "cut-free".

Despite all the mechanisation, the shaping operations, splitting and trimming, are still carried out by hand. In the process, the blocks are divided into slabs about 5 millimeters thick.

In the Wadrill roofing slate mine in the Saarland, which was operated until 1953, the slate blocks had to be extracted by steep to vertical bedding (60°-90°) in ridge butt mining. In the mining chambers, the slate blocks were wedged from the bottom to the top by notches or extracted by a gentle, pushing extraction shot with black powder. Extractable blocks were still created underground by splitting parallel to the schistosity (ripping) or splitting perpendicular to the schistosity (heading).

Slate from Germany

In the interest of orderly competition that is transparent to roofers, architects, traders and builders alike, slate quarries with reasonably comparable characteristics from one region have been grouped together under one name.

As with the well-known vineyard sites, the designation of origin thus became a property and quality indication at the same time. The designations and assignments of the pits were determined after long negotiations between the Reichsdachdeckerhandwerk and the German slate industry in the early 1920s. The result was published in the official part of the magazine "Das Deutsche Dachdeckerhandwerk" of August 7, 1932. The specifications were confirmed again in 1953 and 1967 and are still used by the slate companies today: Mosel slate, Thuringian slate, Hunsrück slate and Sauerland slate.

Accordingly, only the slate from the districts of Mayen, Polch, Müllenbach, Trier and the surrounding area may call itself Moselschiefer. Today, only the Katzenberg and Margareta mines in Mayen still bear the name Moselschiefer. The name comes from the historical transport route of this slate across the Moselle to the Lower Rhine and the Benelux countries. For the districts of Altlay, Bundenbach, Kirn, Gemünden and Herrstein as well as their surroundings, the name Hunsrück slate applies. The extraction sites in Fredeburg, Brilon, Nuttlar, etc. fall under the generic term Schiefer aus Westfalen und Waldeck (slate from Westphalia and Waldeck), but are also simply called Sauerländer Schiefer (slate from the Sauerland), although, as in other regions, there can be significant differences in properties within this designation.

The following are still in production today

- in the Hochsauerland in the area around Bad Fredeburg a compound mine with the mines Bierkeller, Gomer, Magog with a 150-year tradition,

- in the Hunsrück region, the Altlay slate mine (with underground extraction at a depth of about 120 metres below centuries-old quarries). For 2020, the operator of the Altlay mine announced the start of open-pit slate mining in "new, untouched slate deposit[s]".

- in Bavaria near (municipality of Geroldsgrün) (after a 500-metre-long winding tunnel) the Lotharheiler slate.

Moselle slate mining around Mayen was traditionally the most productive German site, accounting for over half of Germany's production. However, the largest known roofing slate deposit is located in the area around Bad Fredeburg.

Until 2008, slate was also mined in Thuringia, where a mine in Unterloquitz and an open-cast mine near Schmiedebach were in operation. From the Middle Ages until partly into the second half of the 20th century, the so-called Wissenbach slates were mined as roofing slate in mines and quarries in the Harz region, especially south of Goslar, including the Glockenberg mine. In Kaub on the Middle Rhine, roofing slate of the highest quality was extracted for centuries until 1972. Today, the surface installations of the Wilhelm-Erbstollen mine still bear witness to the former importance of slate mining for the entire region.

Other mining countries

Shale is found in many countries of the world: also outside Europe in North America, South America, South Africa, Japan, China, Russia (Siberia) and India. In Europe, slate deposits are found in Slovenia, Croatia, Greece, Italy, the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Portugal, Spain, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Great Britain and Ireland.

In terms of volume, significant production is found in Spain, France, Great Britain, Germany and Portugal, in that order. The largest consumer country, however, is by far France. This traditional "slate country" has a formerly important national production (Ardoisières d'Angers), but is also the largest consumer of Spanish slate. Traditional "slate countries" in the sense of use are also Germany, Benelux and Great Britain.

Slate mining in Spain

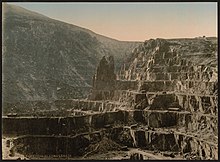

Penrhyn Quarry near Bethesda, Wales, around 1890

Play media file Video: Slate mining in the Eifel. Underground mining in the Margareta pit, 1983

Slate roof

Historic roof slate mine Grube Hoffnung in Hunsrück

Entrance to an old slate mine, Grube Vogelsberg 1 in the Hunsrück.

Slate quarry in Lehesten, Thuringia (1948)

Black and white slate on a half-timbered house in Obercunnersdorf

Museums

Germany

Slate museums include:

- Eifel: German slate mine. It is located at a depth of 16 meters under the Genovevaburg in the town of Mayen.

- Wittgensteiner Land: Slate mine Bad Berleburg-Raumland Slate mine Raumland

- Hochsauerland:

- Slate mining and local history museum Holthausen

- Slate mining museum Nuttlar

- Thuringian Slate Mountains: Thuringian-Franconian Slate Road: Along this approximately 100 km long themed road, you can find

- Slate Museum Ludwigsstadt

- German Slate Museum, Steinach

- Slate Park Lehesten, Lehesten

- Lotharheil slate works, Geroldsgrün

- Morassina show mine, Schmiedefeld

- Fell visitor mine, Hunsrück

Abroad

- Welsh Slate Museum (about the slate industry in Wales)

- Musée de l'Ardoise in 49800 Trélazé (Maine-et-Loire department, Pays de la Loire region)

- Musée de l'Ardoise in Haut-Martelange / Uewermaarteleng Slate Museum L-8823, Luxembourg

- Belgium: 6880 Bertrix

·

Slate-clad cottage in the Thuringian Slate Mountains

·

Boppard am Rhein: older house (natural slate)

·

Slate-roofed houses in Goslar

·

Church and houses in Wurzbach covered and clad with slate

·

Slate retaining walls in the Hamburg Botanical Garden

·

Slate with sponge and rag

·

A house number made of slate

·

Brilon partial view of a slate roof

·

Leonaert Bramer: MORS THRIUMPHANS (painting, oil on slate)

Search within the encyclopedia