Sioux

![]()

This article is about the Indian people Sioux. For the shoe manufacturer, see Sioux (company). For the British musician, see Siouxsie Sioux.

Sioux (French: [sju:], English: [suː], German: [zi:ʊks]) is the name for both a group of North American Indian peoples and a language family. Sioux refers to three groups of closely related languages: Lakota, Western Dakota, and (Eastern) Dakota. The Dakota people served as the namesake for the two U.S. states of North Dakota and South Dakota.

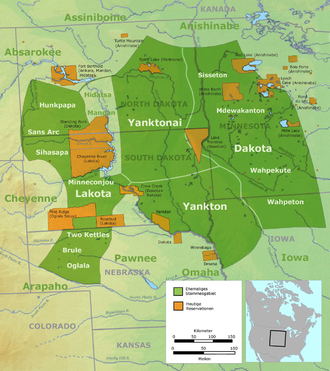

By 1800, these Sioux groups dominated most of North and South Dakota, northern Nebraska, eastern Wyoming, southern Montana, northern Iowa, and western Minnesota. The Assiniboine, who had split from the Yanktonai Sioux, dominated the southern Canadian prairie provinces as well as northeastern Montana and northwestern North Dakota. The Stoney, closely related to them, lived mostly north and west of the Assiniboine on the prairie provinces, roaming from southern British Columbia to northern Montana.

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, 170,110 people in the United States identified themselves as members of the Sioux Nation.

Linguistically related are the Absarokee, Hidatsa, Iowa, Kansa, Mandan, Missouri, Omaha, Osage, Oto, Ponca, Quapaw, and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) tribes.

Former tribal territory of the Sioux and neighboring tribes and present reservations

Name

The term Sioux is a colonial French short form of the Ojibwa word "Nadouessioux" (little snakes), which in turn is a French spelling for the Algonkin word "Natowessiw", plural "Natowessiwak". From this swear word is derived "Nadowe-is-iw-ug", meaning "they are the lesser enemies". Sioux is the only name for all seven tribes attributed to this group.

The lexeme "Sioux" is a derogatory term used by the Anishinabe to refer to a number of Native American tribes of the Dakota/Lakota group and linguistically related tribes, all enemies of the Anishinabe. However, some linguists have pointed out that with respect to proto-Algonkin terminology, the lexeme can also be reinterpreted as "speaker of a foreign language." In contrast, other linguists point out that it was quite typical to speak of one's enemies as "snakes." This is also the reason why the Shoshone were called "snake Indians". Another problem with the reinterpretation of the term is that Proto-Algonquian is merely a reconstructed language spoken thousands of years ago.

Culture and way of life

The Sioux shared many cultural traits with other Plains Indians. They lived in tipis, a word from the Sioux language. The Lakota roamed in these tents year-round, the Dakota only during hunting in summer and winter. The men gained reputation by brave deeds both in war and hunting, by generosity and wisdom. Capturing horses and scalps while raiding enemies was evidence of courage, bravery, and skill. Warfare and supernatural matters were closely linked, so that figures, patterns, and symbols perceived in mystical visions were painted on their shields, horses, teepees, and eventually (for ceremonies and war campaigns) on their faces to protect the wearers from their enemies and evil spirits. The Sioux practiced a carefully crafted form of the Sun Dance, which they called the Chief Tribal Festival.

Their religious system knew four powers that ruled over the universe, which in turn were divided into four hierarchies. The basis of these powers was wakan, the mysterious life and creative force, which in sum was called the world soul Wakan Tanka (Great Mystery). Things, natural phenomena or people with outstanding or unusual qualities were also wakan, for in them the existence of the supernatural powers (animism) was revealed. The buffalo figure also had an important place in their traditional religion. Among the Teton, the bear was the most important figure; the appearance of the bear in a vision was regarded as a healing power. The Santee Sioux held a ceremonial bear hunt to gain protection for their warriors before leaving for a war campaign.

Sioux women were skilled at needlework with porcupine bristles and beadwork that displayed geometric patterns. Policing functions were performed by military societies whose most important task was to supervise buffalo hunts. Other societies took care of dancing and spiritual rituals. There were also women's societies.

Seasons and their activities

The months of a year were named after the most important activities and events. Summer months bore names of ripening fruit, such as "Strawberry Month" (May), "Ripe Rock Pear Month" (June), "Ripe Cherry Month" (July), and "Ripe Plum Month" (August), which were harvested by the Sioux. Some months were named after seasonal phenomena, such as the "Month of Yellow Leaves" (September) and the "Month of Falling Leaves" (October). November was the "Month of Hairless Calves" because bison were slaughtered during this month and their embryos were hairless. The winter months were called "the month of frost in the tepee" (December) and "the month when the trees burst" (January). "The Month of Sore Eyes" referred to the snow blindness from which many suffered in February. March was the "month when the seed sprouts" and April, the beginning of the year, was the "month of the birth of calves".

In the spring, family groups left the main camp to gather meat and food. It is likely that the Sioux had a large supply of wapitis, pronghorn, and bison during this time. In the spring months, Dakota men and women tapped the sap of the ash maple to make syrup. In the warmer months, the eastern Sioux peoples occupied wigwams made of tree bark. The tipis were renewed or mended with fresh hides on this occasion. At the beginning of summer the hides were smoked and made into leggings or moccasins. In May or June they moved to higher ground. This migration was traditional and often associated with hunting when food was scarce. Most of the summer was spent holding ceremonies such as vision quests, cultic celebrations, tribal elections, and festivals honoring female virtues. The highlight of the celebrations was the Sun Dance. Then an elected group decided on fall activities. At the end of the summer, fall hunts were organized, which they called "Tates." Autumn was a busy time for the women, who gathered berries and nuts and dried the meat to prepare pemmican for the winter. When autumn ended, the Sioux moved to winter camps protected from the elements. While the Lakota did not farm, the Dakota cultivated corn, beans, and squash.

The bison hunt

The Sioux were originally arable farmers who only occasionally hunted bison. It was not until they adopted the horses introduced by the Spanish in the 1700s that they can be considered nomadic bison hunters. Hunting was the men's job. There were huge herds of bison on the prairies and high plains, as well as pronghorn, wapitis, rabbits, and porcupines, and beaver and ducks on the riverbanks. The animal that dominated the Great Plains was the bison. Although archaeological evidence shows that this animal was widespread in North America, by the 19th century its habitat was limited to the Plains, which were populated by some 60 million bison. The bison has poor eyesight, but its sense of smell and hearing are exceptionally good, so that Indian hunters had to sneak up against the wind.

The early unmounted Indians of the Plains hunted the bison by panicking the animals. The animals, rushing away in wild flight, were forced into a V-shape and driven to a cliff, from which they plunged. At such places thousands of animals were killed every year, so many at the same time that it was impossible to consume all the meat.

After the arrival of the horse on the Great Plains, the Sioux cultivated hunting on horseback. Crucial to hunting success was the quality of the horse. It had to have stamina, because even a fatally shot bison bull could still run far before collapsing. It had to possess courage and be able to dodge the pointed horns thrusting at it with great skill. Such a horse was guarded by the family, and when thieves from hostile tribes were near, the horse came into the tepee and the women had to sleep outside.

For bison hunting, the hunter was dressed only in leather loincloth and moccasins. He was armed with a short lance or with a bow and about 20 marked arrows, by which the shooter was later recognizable. If the hunter was close enough to the selected bison, he tried to hit a spot behind the last rib. It usually took at least three hits to bring down the animal. Bison hunting was a dangerous affair, and many a horse and hunter fell victim to it.

The bison was of central importance to the Sioux and was revered as a sacred animal. It provided Indians with the essentials needed to survive on the high plains: Food, shelter, and clothing. The skin of bison calves was used to make soft diapers for newborns. The hides of six to eight adult animals made the cover of a tepee for the entire family. Bison skin was also used to make the soles of moccasins, clothing, bags, various straps and, last but not least, boats. The particularly thick neck fur was used to make shields, cooking pots were made from rumen and the sinews were used as yarn, for example, to bind the skins together. The bones were made into scrapers, knives and awls. The Sioux made sleds from ribs connected with straps. The thick winter skins provided protection and warmth against the biting cold on the Plains. The fur was also used to pad cradle boards and pillows. There were tokens made of bone, dolls made of bison hide, and toys made of horn. Ornaments were made from dyed bison hair, and bison tails decorated tepees. The beard of the animals decorated clothing and weapons, horns and hair served as headdresses. Medicine pouches were made from the bladder, and the Indians used hooves and scrotums to make rattles for ceremonial purposes.

Construction of a tepee

The tipi, which belonged to the women, protected them from heat in summer, from cold in winter and could even withstand stormy winds. The erection and dismantling of the tepee was women's work, with two women taking little more than an hour to erect it. The tepee usually consisted of a covering of scraped bison hides sewn together with sinew and pulled over a pole frame. The Sioux used a tripod of particularly strong poles for the framework, which were tied together at the top with straps. Then the remaining poles were leaned against it and also tied tightly. Finally, the connection to a wooden stake inside served as an anchor against storm gusts. The folded leather cover was moved into position with a lifting pole, pulled over the scaffold, and secured at the bottom edge with wooden stakes in the ground. The open vertical seam was closed with wooden sticks and placed under a door flap. Finally, two thin poles were inserted outside the tipi into the pockets of the smoke flaps, which could be used to adjust the smoke vent to the wind direction or to close it completely. The normal Sioux tepee was about five feet in diameter at the base and could hold an entire family.

Sioux tepees, painted by Karl Bodmer, 1833

Sioux baby carrier

Sioux Camp, 1894

American bison

Sioux woman dress

Search within the encyclopedia