Silk Road

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Silk Road (disambiguation).

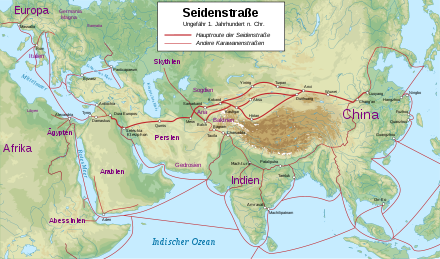

As Silk Road (Chinese 絲綢之路 / 丝绸之路, Pinyin Sīchóu zhī Lù - "the route / road of silk"; Mongolian ᠲᠣᠷᠭᠠᠨ ᠵᠠᠮ Tôrgan Jam; short: 絲路 / 丝路, Sīlù, Persian: جاده ابریشم) refers to an ancient network of caravan routes, the main route of which connected the Mediterranean region with East Asia by land via Central Asia. The term originates from the 19th-century German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, who first used the term in 1877.

The ancient Silk Road was mainly used to trade silk to the west and wool, gold and silver to the east (see also trade with India). Not only merchants, scholars and armies used their network, but also ideas, religions and entire cultural circles diffused and migrated along the routes from East to West and vice versa: Nestorianism (from the late Roman Empire) and Buddhism (from India), for example, came to China via this route. However, recent research warns against overestimating the volume of trade (at least overland) and the transport infrastructure of the various trade routes.

A 6,400-kilometer route began in Xi'an and followed the course of the Great Wall of China to the northwest, passing through the Taklamakan Desert, overcoming the Pamir Mountains and leading via Afghanistan to the Levant; from there, the trade goods were then shipped via the Mediterranean. Few merchants traveled the entire route; goods tended to be transported in a staggered fashion via intermediaries.

The trade and route network reached its greatest importance between 115 B.C. and the 13th century A.D. With the gradual loss of Roman territory in Asia and the rise of Arabia in the Levant, the Silk Road became increasingly unsafe and little traveled. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the route was revived under the Mongols; among others, at the time the Venetian Marco Polo used it to travel to Cathay (China). It is widely believed that the route was one of the main routes by which plague bacteria reached Europe from Asia in the mid-14th century, causing the Black Death.

At present, there are several projects of the People's Republic of China under the name of "New Silk Road" for the development especially of the transport infrastructure in the area of the historical Silk Road.

The network of the ancient Silk Road and trade routes connected to it

Meaning

Not only silk, but also goods such as spices, glass and porcelain were transported on the Silk Road; religion and culture also spread with the trade. Buddhism, for example, reached China and Japan via the Silk Road and became the predominant religion there. Christianity reached China via the Silk Road. The knowledge of paper and black powder came along the Silk Road to the Arab countries and from there later reached Europe.

Trade goods

Silk was probably the most extraordinary trade good for the West that passed through the Silk Road. After all, this fabric also gave the route its name. Nevertheless, this term distorts the reality of trade, because many other goods were also exchanged via these trade routes. Caravans heading to China carried gold, gems, and especially glass, among other things, which is why researchers have pointed out that from an eastern perspective, the "Silk Road" could just as easily be called the "Glass Road." In the other direction, apart from silk, the main goods carried were furs, ceramics, porcelain, jade, bronze, lacquers and iron. Many of these goods were exchanged en route, changed hands several times and thus gained in value before reaching their final destination.

In addition to silk, spices in particular were important trade goods from Southeast Asia until modern times. They were used not only as seasonings and flavourings, but also as medicines, anaesthetics, aphrodisiacs, perfumes and for "magic potions".

Nevertheless, the most sought-after Chinese product was silk. The development of silk weaving in China can be traced back to the 2nd millennium BC. The production of large quantities for export, accompanied by the formation of silk manufactories, did not take place until the end of the "Time of the Contested Empires" in the 3rd century B.C. The oldest finds of Chinese silk in Europe were made in the Celtic princely tomb at Heuneburg (Sigmaringen district), which dates back to the 6th century B.C..

In the Roman Empire, like purple and glass, it was one of the luxury items. Only the richest could afford modest quantities of the precious material. In the time of the Pax Augusta, when the western end of the Silk Road was also secure, the Roman upper class increasingly demanded eastern silk, spices and jewels. Although the Eastern Romans under Emperor Justinian I finally succeeded in establishing their own silk production in late antiquity with the help of smuggled-in caterpillars, the import of Chinese silk remained very significant.

Organization of the trade

Bandits and robbers were very often a problem of security because of the large flow of goods and riches. The Han Empire therefore equipped its caravans with special escort protection and extended the Great Wall to the west.

The organization of transcontinental trade was complex and difficult. Countless animals, a large number of drovers and tons of trade goods had to be organized and moved. In the process, people and animals had to be cared for on the long journey under difficult geographical and climatic conditions. Usually, however, the merchants did not travel the entire route to sell their goods. Rather, trade took place over various sections of the route and several intermediaries. While the western end of the Silk Road was long controlled by the Parthians and later the Sassanids, in Central Asia it was mainly various groups of equestrian tribes (see for example Xiongnu, Iranian Huns, Kök Turks) that dominated the exchange of goods.

An important role was played by Sogdian traders, whose contacts extended as far as China. Preserved letters of Sogdian traders are also an important source for the history of the Silk Road.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish Radhanites also used the Silk Road. In addition to oases, the route was also interrupted by military stations such as stopping points for changing horses, which ensured through traffic.

The Bactrian camel, which was native to Central Asia, was of great importance as a means of transport. It has the advantage that it is more heat-resistant than dromedaries and has a winter coat, so that it is well adapted to the extreme temperature fluctuations typical of continental climates in the steppe and mountain regions with large differences in altitude.

Recent research warns that the volume of overland trade and the transport infrastructure of the various trade routes was often overestimated, because the Silk Road was not a single, continuous route from east to west. Transportation often involved the handling of goods at various stations and was time-consuming. Moreover, older research did not sufficiently appreciate the importance of the transfer landscapes, such as Central Asia and Persia.

Culture and technology transfer

The transfer of technical achievements, cultural goods or ideologies was less intentional than the exchange of goods. Long-distance travel of all kinds, whether for commercial, political, or missionary reasons, stimulated cultural exchange between different societies. Songs, stories, religious ideas, philosophical views, and unknown knowledge circulated among travelers. For several centuries, the Silk Road formed the most enduring, far-reaching, and diverse exchange between the Orient and the Occident.

In addition to the introduction of new foods, an agri-cultural exchange also took place.

Important techniques such as papermaking and letterpress printing, chemical processes such as distillation and the production of black powder, as well as more efficient horse harnesses and the stirrup were spread from Asia to the West via the Silk Road.

diffusion of religions

One particularly long-lived commodity that was transported via the Silk Road was religions. Buddhism, for example, came from India to China and Japan via the northern route. Some of the earliest descriptions of the Silk Road come from Chinese pilgrims traveling to the Indian homeland of Buddhism.

Mongols and Turkic peoples originally worshipped the sky god Tengri, in Iran and Parthia Zoroastrianism prevailed, while in Sogdia a separate folk faith was widespread.

Christianity was present early in Asia Minor and Iran. In the 5th century, the East Syrian Church, adhering to Nestorianism, was formed in the Sassanid Empire. At this time Nestorianism was able to spread into the eastern Iranian area as far as Sogdia and Bactria. In the 8th century Samarkand was reached. In the Tarim Basin there was a first missionary wave in the 8th century and a second in the 11th century. In the Transylvanian region, many Nestorian tombstones were erected in the 9th-14th centuries. Even earlier, believers reached the then capital of China, Xi'an, as documented by a stele erected in 781. A Chinese edict of 845 turned against all foreign religions and caused Nestorianism to disappear here by the 10th century. With the Mongol rule it experienced a second heyday and then finally disappeared in China in the 14th century. Among the Turkic peoples, the faith also persisted until the 14th century, when it was eradicated by Timur Lenk, who adhered to Islam.

Manichaeism arose in Mesopotamia from AD 240 and spread rapidly in Persia, where it failed to prevail against Zoroastrianism, and in the lowlands of Turan to the east. He was able to gain believers in Turfan, Merw, and Parthia. In the important trading colonies of the Sogdians, numerous Manichaeans were found alongside Nestorians and Buddhists, as they were in 7th-century China. In 762 the rulers of the Uighur steppe kingdom professed Manichaeism, and in the kingdom of Kocho this religion also held a strong position alongside Buddhism. In Dunhuang the Manichaeans disappeared in the 11th century, and in Turfan not until the Mongol period in the 13th century.

Buddhism developed at the turn of time in the Indo-Iranian border region, in Gandhara and in Kushana, under Hellenistic influence, the formal language with the human Buddha figure. Kanishka I, king of the Kushan Empire, was a promoter of Buddhism in the Middle Silk Road area for political reasons; the religion gained many followers in Sogdia in the 3rd and 4th centuries. Buddhism first reached China at the turn of the twentieth century, strengthened during the Northern Wei dynasty in the 4th and 5th centuries, but it did not have a widespread impact until the 7th century. After the Mongols under Kublai Khan came into increased cultural contact with China in the 13th century, Buddhism also gained adherents. In East and West Turkestan Buddhism dwindled with the advance of Islam, and in the Tarim Basin not until the 15th century. In Dunhuang and China it was unthreatened.

These three religions coexisted more or less peacefully for a long time in many places along the Silk Road. After the death of Muhammad in 632 AD, Islam spread (Islamic expansion) and soon the western part of the Silk Road, and with it trans-Asian trade, was also under Islamic control. After the conquest of the New Persian Sassanid Empire in 642 AD, expansion continued in an easterly direction. Islam spread first to urban centers along the Silk Road and later to rural areas. Islamic communities also emerged in Central Asia and China. Under Timur Lenk, Islam was again spread by force in the 14th century.

disease spread

Just like religious beliefs or cultural goods, diseases and infections repeatedly spread along the Silk Road. Long-distance travellers helped pathogens to spread beyond their area of origin, attacking populations that had neither inherited nor acquired immunity to the diseases they caused. This gave rise to epidemics that could have dramatic consequences.

Probably the best-known and most consequential example in Europe of the spread of diseases along the Silk Road is the spread of the plague in the 14th century. According to a hypothesis by the author William Bernstein, the Pax Mongolica that followed the Mongol invasion in the 13th century again allowed intensified and direct trade contacts between Europe and Asia. This lively exchange also brought plague bacteria, found primarily in wild rodent populations of Asia, to Europe. The plague also reached Central Europe around 1348 via merchant ships from Kaffa on the Crimean peninsula. The transport of furs was particularly conducive to its rapid spread. In this context, it is unclear why the Black Death did not claim a comparable number of lives in China and India. In the similarly densely populated India of the 14th century, there was even a population increase; in the much more densely populated China, more people died from famine and the wars against the Mongols than from the Black Death. There is also no historical record of a pandemic comparable to the Black Death in Europe.

The Plague in Phrygia , copperplate engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi, 1515/16

Manichaean priests, wall fresco from Khocho, Xinjiang, 10th/11th century AD (Museum of Asian Art in Berlin-Dahlem)

A West Asian and a Chinese monk, Bezeklik, 9th century.

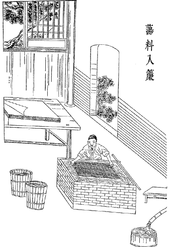

Chinese illustration of paper making, 105 AD.

A European trader on the Silk Road in the eyes of a Chinese artist (Tang dynasty, 7th century)

Chinese customs station on the Silk Road near Dunhuang

History

To the nature

The Silk Road was anything but a route dictated by nature. Running from the Mediterranean to China through arid lands and deserts, it is one of the most inhospitable routes on earth, running through scorched, waterless land and connecting one oasis to the next. Mesopotamia, the Iranian Highlands and the lowlands of Turan lie along the way. Once you have reached the Tarim Basin with the Taklamakan Desert, you are surrounded by the highest mountain ranges on earth: the Tian Shan rises in the north, the Pamir in the west, the Karakorum in the southwest and the Kunlun in the south. Only a few icy passes, which are among the most difficult in the world with their deep gorges and 5000 metres of altitude to overcome, lead through the mountains. The climate is also harsh: sandstorms are frequent, in summer the temperature rises to over 40 °C and in winter it often drops below -20 °C.

Precisely due to the geographical nature, only a few fixed traffic and trade routes developed. In many places there were alternatives and alternative routes.

Main route

Mostly the name "Silk Road" refers to the route described here, which has some branches, and which because of its length is again divided into a western, central and eastern part.

The core of the Silk Road, sometimes called the Middle Silk Road, stretches from the East Iranian plateau and the city of Merw in the west to the Gobi Desert and the city of Dunhuang in the east, as well as the branch south to Kashmir and Peshawar. It connects three of the most important Asian cultural areas: Iran, India and China. The country is characterized by deserts with ancient oasis cities, the Kazakh steppe in the west and the Mongolian steppe in the east, and high mountains.

The main route is divided into several branches. From Merw one could cross the Oxus (today Amudarya) and reach the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand located in Transoxania.

From there, a northeast branch led via Tashkent north of the Tian Shan Mountains via Beshbaliq (near Ürümqi) and via Turpan (Turfan), Hami (Kumul), rejoining the main branch at Anxi (today Guazhou).

The main branch followed the upper course of the Jaxartes (Syrdarja) from Samarkand through the Ferghana Valley, which was irrigated by it, via Kokand (Qoʻqon) and Andijon, crossed the Tian Shan Mountains, and reached Kashgar (Kaxgar) in the Tarim Basin.

The Taklamakan Desert, located in the Tarim Basin, could be bypassed to the north or south. Along the southern edge, one went via Yarkant, Khotan (Hotan), Yutian, Qarqan, Keriya, Niya, Miran and Qakilik, until finally reaching Dunhuang. From the 2nd century, when a change in climate brought more water to the region, this was the usual route.

Later, the oases on the southern rim dried up again, and from the 5th century onwards the route along the northern rim became common: from Kashgar (Kaxgar) one went via Tumshuq (Tumxuk), Aksu, Kuqa (Kucha), Karashar, Korla, Loulan and finally one also reached Dunhuang.

From Kuqa (Kucha) there was another branch northeast to Turpan (Turfan) and then on like the northeast branch described above. The land of the seven rivers was also connected by paths.

To reach India, very high mountains had to be crossed. From Merw, one reached the Khyber Pass along the upper reaches of the Oxus (Amu Darja) via Baktra (today Balkh), crossed the Hindukush and reached the northwestern Indian province of Gandhara to Begram, Kapisa and Peshawar.

From the 3rd century onwards, another route was also used: from the upper Indus Valley via Gilgit and the Hunza Valley, the Karakorum Mountains were crossed and the Tarim Basin reached at Kashgar (Kaxgar). This route corresponds to the course of the Karakorum Highway built from the 1960s onwards.

The Eastern Silk Road joins the Middle Silk Road to the east and leads to the important cities of China. It led from Dunhuang east via Anxi (today Guazhou) through the Gansu or Hexi Corridor via Jiayuguan (up to here the Great Wall was built to protect the trade route), Zhangye and Wuwei to Lanzhou, then via Tianshui and Baoji to Chang'an. From there it went northeast to Beijing or east to Nanjing.

The Western Silk Road, also called the Great Khorasan Road, connects westward to the Middle Silk Road and leads to the port cities on the Mediterranean Sea. It led from Merw via Tus (Mashhad), Nishapur, Hekatompylos (later Damghan), Rhagae (later Ray), Ekbatana (later Hamadan) and Babylon (later Baghdad) to Palmyra. From there it went northwest via Aleppo to Antioch (today Antakya) and Tyros to Constantinople (today Istanbul) or southwest via Damascus and Gaza to Cairo and Alexandria.

Other routes

- From the upper Indus valley to the port of Debal in present-day Pakistan at the mouth of the Indus. From there by ship to Mesopotamia or around the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt.

- A variation of the previous route, but this time via the port of Barygaza (Bharuch), further east on the Gulf of Khambhat.

- From Samarkand on the Jaxartes (Syr-Darya) through the Kazakh steppe and the Caspian depression to the Crimea and the Black Sea.

- Extension from the Chinese cities to Korea and Japan.

- From the Chinese port cities by ship along the coast through the Strait of Malacca to the ports on the Indian east coast, around the Indian peninsula to the ports on the Indian west coast. From there to the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia or the Red Sea and Egypt or Palestine.

- From the southwest Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan via Burma to Bengal and the trading cities in the delta of the Ganges and Brahmaputra.

- From China via Tibet to Bengal.

- On the paths connected with the Silk Road through the Eastern Pamirs, the Pamir Road was built in the 1930s.

Important trade routes in Asia in the 1st century, bold marks the main route of the Silk Road

The overall course of the main route of the Silk Road in the Middle Ages

Taklamakan near Yarkant

The core of the Silk Road in the Middle Ages

Tian Shan Mountains

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Silk Road?

A: The Silk Road was a group of trade routes that went across Asia to the Mediterranean Sea.

Q: Why was it called the Silk Road?

A: It was called the Silk Road because silk was traded along it. At the time, silk was only made in China, and it was a valuable material.

Q: What did the Silk Road do for China?

A: The Silk Road not only earned China a lot of money, but all along the route cities prospered and markets flourished.

Q: What were some of the cities built on the Silk Road?

A: Cities like Samarkand and Bukhara were built largely on the trade from the silk route.

Q: What cultures did trade on the Silk Road contribute to the growth of?

A: Trade on the Silk Road played a big part in the growth of the ancient cultures of China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, India, and Rome.

Q: What was the origin of the term "Silk Road"?

A: The term Silk Road is English for the German word "Seidenstraße". The first person who called it that was a German geographer in 1877.

Q: What is the significance of the Silk Road today?

A: The Silk Road helped to make the beginning of today's world.

Search within the encyclopedia