Shifting cultivation

Shifting cultivation is a traditional form of agriculture where the fields are used intensively for only a few years and then the land and settlements are moved, i.e. in a form of semi-settlement.

The time for moving is reached when declining soil fertility no longer permits sufficient yields. Shifting cultivation is one of the oldest forms of agricultural use on earth and ideally provides sufficient food for a self-sufficient subsistence economy with optimal ecological adaptation to local environmental conditions. Today, it is mainly the ever-humid tropical rainforests and the alternating humid savannahs that are affected by this type of farming. Especially tuberous plants such as cassava, taro or yams are cultivated in this way. About 250 million people are currently dependent on this small-scale, extensive form of agriculture. The term shifting cultivation is often replaced in current German-language literature by the English term shifting cultivation.

Shifting cultivation is also referred to as slash-and-burn agriculture, as this type of cultivation is usually associated with the prior slash-and-burn clearing of "forest islands". In slash-and-burn agriculture (or rather slash-and-burn, because the roots are not removed as in real clearing), the substances contained in the plants remain as ash on the planned cultivation area and ensure a higher pH value of the very acidic tropical forest soils in the short term. This improves the growing conditions for the food crops. The additional release of plant nutrients from the ash is of much less importance than was previously assumed. If the diverted biomass is only charred instead of burned, the resulting wood and plant charcoal is subsequently incorporated into the soil; it contributes significantly to soil improvement because its particularly large internal surface area enables it to buffer water and nutrients (→ activated carbon). This procedure also appears to be the origin of the "black earth" (terra preta) found in the Amazon basin of South America.

Today, shifting cultivation is practised mainly by indigenous population groups and traditional ethnic groups, where they cultivate land for 2 to 4 years and then move the fields to renewed slash-and-burn areas, so that (with classically low intensity of use) a secondary forest with fewer species grows on the previous cultivated area in the following years. Former slash-and-burn areas need 15 to 30 years before they can be used again in an economically and ecologically sensible way.

The transitions from shifting cultivation to spatially more restricted and stationary forms of farming with alternation between cultivation and fallow land are fluid. If only the farmland and the farm sites are not relocated or are relocated only after several cycles in alternating rotation, this is referred to as shifting cultivation.

"Patchwork" landscapes, like this one in southern China, emerge when settlement in traditional shifting cultivation areas becomes too dense

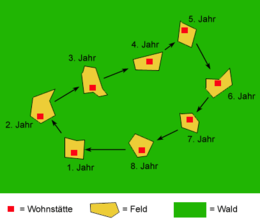

Example cycles of a typical shifting cultivation over nine years

Typical "hole" after slash and burn in the forest to create a field of shifting cultivators (here the Jumma in Northeast India)

Transitions to other economic forms

Shifting cultivation is - at population densities below 6 inhabitants per km² - an efficient and adapted agricultural strategy on poor and fragile soils, which are common in the tropics. However, shifting cultivation was also practised in temperate latitudes in the past. If, in the past, climatic factors or increasing population pressure led to declining yields, people were forced to migrate or to develop new technologies that allowed intensification of agriculture. The resulting overuse usually leads to such severe degradation of the soil that the reduced soil fertility does not allow further cultivation of the area. This is how the field economy was introduced in Europe or the land rotation economy in the tropics. This was the case, for example, in Central America (milpa agriculture of the Maya) - partly supplemented by irrigation measures - or also among West African field farmers.

The modern "population explosion" and the destruction of ever larger areas of forest also call for solutions in order to be able to continue to sustainably feed the forest dwellers. One promising approach to sustainable intensive use is to supplement the short-term soil improvement of slash-and-burn agriculture (melioration) with the deliberate addition of extra charcoal, human feces, manure, compost, and the like. This insight is not even new, as many indigenous peoples of the Amazon (example Tupí) have produced and used this anthropogenically modified soil, now called terra preta, for centuries.

Nutrient cycle and regeneration phase

The length of the required fallow phase has a direct impact on population density: the longer it lasts, the fewer people can live off shifting cultivation in a given area. The length of the fallow phase depends on the type of use and crops, climatic conditions and soil quality. In tropical soils, which are usually deeply weathered and nutrient-poor, the regeneration phase can last up to 30 years. Due to the tropical conditions such as humidity and temperature and due to the high age of the soils, their minerals can store only few nutrients (low cation exchange capacity, CAC). The nutrients are therefore almost exclusively contained in the biomass (mainly plants, but also animals and microorganisms) and in the humus, i.e. the organic fraction of the soil. Many are in a short-circuited cycle (tropical nutrient cycle).

Slash-and-burn increases solar radiation and thus the soil temperature, which causes increased mineralisation, reducing the humus content to such an extent that only a few nutrients can still be stored there. After slash-and-burn, most of the nutrients are initially in the ash, from which a high proportion is then lost through precipitation: Thus, they are either washed away directly at the surface by heavy rains, or the downward soil water flow washes the nutrients to such great depths that they are no longer reached by the roots of the crop plants. The nutrient content of the topsoil is reduced, making further cultivation no longer worthwhile. However, if sufficiently long fallow periods are observed, deep-rooted fallow trees can take up nutrients and a secondary forest can form. This also leads to the rebuilding of humus in the soil.

Search within the encyclopedia