Shamanism

![]()

This article is about traditional shamanism - for the modern spiritual movement see neo-shamanism.

Shamanism refers in a narrower sense to the traditional ethnic religions of the cultural area of Siberia (Nenets, Yakuts, Altai, Buryats, Evenks, also European Sámi and others), in which the presence of shamans was considered by European researchers of the expansion period as an essential common characteristic. For better differentiation these religions are often called "classical shamanism" or also "Siberian animism".

In a broader sense, shamanism means all scientific concepts that postulate the cross-cultural existence of shamanism due to similar practices of spiritual specialists in different traditional societies. According to László Vajda and Jane Monnig Atkinson, due to the multitude of different concepts, it should be more apt to speak of shamanisms in the plural.

Siberian shamans and various necromancers of other ethnic groups - who are also often generalized as shamans - had or have alleged influence on the powers of the afterlife in many traditional worldviews. They used their abilities primarily for the benefit of the community, to restore "cosmic harmony" between this world and the other in crisis situations that seemed intractable. In this broad sense, shamanism designates a series of vaguely defined phenomena "between religion and healing ritual".

A more detailed, generally valid definition is not possible, since the definition contains different views from the perspective of ethnology, cultural anthropology, religious studies, archaeology, sociology and psychology. One of the consequences of this is that information on the spatial and temporal distribution of "shamanisms" varies considerably and is disputed in many cases. The American ethnologist Clifford Geertz therefore already in the 1960s denied the "Western idealistic construct of shamanism" any explanatory value.

There is agreement only on the "narrow definition" of classical Siberian shamanism - the starting point of the first "shamanisms". This includes above all the exact description of the ritual ecstasy practiced there, a largely coinciding ethnic religion as well as a similar cosmology and way of life.

According to broader definitions, shamanism is considered an early, cross-cultural stage of development of any religion until the 1980s. Above all, the concept of core shamanism by Michael Harner is to be mentioned here. However, this interpretation is now considered to lack consensus. Since the 1990s, the aspect of "healing" has often been the focus of interest (and the respective definition).

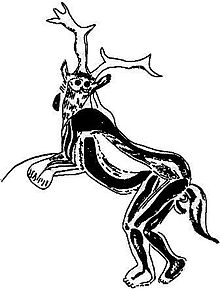

In contrast, the Indologist Michael Witzel assumes that there was an older prototype of shamanism, given the similarity of Australian, Andaman, Indian and African initiation rituals with the corresponding Siberian rituals, which include the phenomena of rising heat, trances (Dreamers), ecstasy and collapse, symbolic death and rebirth, use of psychoactive drugs, keeping taboos, magic and healing. This had spread with the out-of-Africa migration of modern man along the coasts of the Indian Ocean and early to Eurasia and North America. Late Paleolithic bear cults and rock carvings such as in Les trois frères (fig. see below) speak for this. Siberian shamanism represents a younger evolutionary stage of this prototype (with fur clothing, drum, etc.); it had a secondary influence on the North American hunter cultures via further waves of migration. In place of the sacrifice of wild animals, which the shaman asks beforehand for permission to kill or to which he apologizes for the deed (so in the bear cults of the shamans of the Ainu, Aleuts and the Transbaikalian peoples), domesticated animals such as the reindeer (in Siberia) or dogs (as in Russia or India) later took their place. In this respect Witzel follows the broad phenomenological definition of shamanism by Walter and Fridman.

Since already the classical shamanism of Siberia shows several variants, further reaching geographical or historical interpretations, which consider such phenomena detached from their cultural context and generalize, are criticized by many authors as speculative. In contemporary literature - popular science (especially esoteric) books, but also scientific writings - it is often not made clear in this context to which ethnic groups representations of certain shamanic practices refer concretely, so that regional (often Siberian) phenomena are also located in other cultures, in whose traditions, however, they are actually foreign. Examples of this are the world tree and the entire shamanic cosmology: mythological concepts anchored in Eurasia that are equated here with similar archetypes from other parts of the world, thus creating the misleading image of a unified shamanism. Witzel, however, sees in the Eurasian (Germanic, Indian, Japanese, etc.) conception of the tree of life that has to be climbed, respectively in the world tree only an analogy to the older conception of the shamanic flight, which has nothing to do with other tree myths.

In particular, the extremely successful books by Mircea Eliade, Carlos Castaneda and Harner have created the "modern myth of shamanism", suggesting that it is a universal and homologous religious-spiritual phenomenon. In view of the great interest among the population, some authors point out that shamanism is not a single ideology or religion of certain cultures. Rather, they say, it is a scientific construct from a Eurocentric perspective to compare and classify similar phenomena around spirit summoners of different origins.

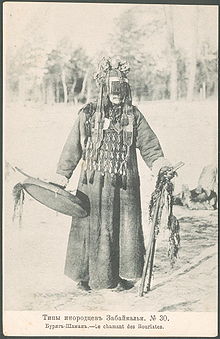

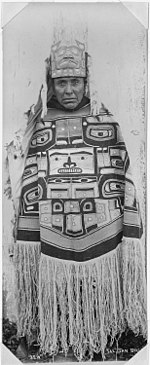

Buryat shaman with drum in ceremonial garb (1904) - classical Siberian shamanism often serves as a paradigm for a wide variety of shamanism concepts.

"Shaman" from Amazonia (2006) - however, the occurrence of shamanism beyond Eurasia is controversial from a scientific point of view.

Etymology

According to most authors, the term shamanism derives from the word "shaman" borrowed from Siberia, which the Tungusic peoples use to refer to their spirit summoners. The word probably derives from the Evenkian (i.e. Tungusian) šaman, whose further etymology is disputed. Possibly the Manjurian verb sambi, "to know, to know, to see through," underlies it. The older term "shamanism" does not refer to the scientific concepts, but only to the existence of spirit conjurers in different cultures, without establishing certain connections.

(For more information see: Etymology in the article "Shaman").

Shamans and shamanism

→ Main article: Shaman

In general, the term shaman, borrowed from Siberia, is used to describe spiritual specialists who have (allegedly) "magical" abilities as intermediaries to the spirit world. Such spirit conjurers are part of many ethnic religions, but also of some folk-religious expressions of world religions. Primarily among some indigenous or traditional local communities, shamans still play an important role today (→ "Traditional spiritual specialists of the present in the light of history" in the article Shaman).

Since the first descriptions of such spiritual experts in various societies, European ethnologists have attempted to identify similarities and possible patterns and to deduce connections.

The existence of a shaman is undoubtedly a prerequisite for any shamanism thesis, but not necessarily the central idea. It is often more about religious beliefs, rites and traditions, rather than the prominent role of the shaman. In this respect, the various conceptually divergent definitions arose.

The shamans are integrated into the lifeworld and natural environment of their respective cultures and cannot be regarded as the embodiment of a particular shamanistic religion or cosmology. Thus, shamanism is closely related to healing the sick, funeral rites, and hunting magic. Michael Lütge compares his role to the "anamnesis of the parish priest at the condolence visit," who tracks down biographical fragments of the dead person that "beckon" to him from the immediate circle of relatives. In other situations, he practices "anticipative[...] hunting propaedeutics similar to the school fire drill."

George Catlin's depiction of a Blackfoot Indian shaman (Medicine man) performing rites over a dying chief.

History of Science

→ Main article: Shamanism research

"Shamanism is not a single religion, but a cross-cultural form of religious perception and practice."

- Piers Vitebsky

Since the end of the 17th century there are detailed reports about the shamans of Siberia and their practices. The attitude of the Europeans to it oscillated several times between respect and contempt back and forth. In the beginning, these reports evoked only aversion and incomprehension. In the course of German Romanticism, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction and shamans were glorified as "charismatic geniuses".

Scientific research in the context of ethnology is also characterized by this great discrepancy: At first, shamans were considered pathologically psychotic and their expressions were called "Arctic hysteria." Later, epilepsy or schizophrenia were related to shamanism.

But already at the beginning of the 20th century, the special social position of the Siberian "Master of Spirits" and the legitimation of his actions in the respective cultural and historical context were examined in detail from a sociological and psychological point of view: he was legitimized to perform techniques that other members of society also mastered in everyday life. Shirokogoroff found during his field research among the Evenks and Manchus that shamans were indeed often neurotic individuals; however, he distanced himself from the widespread explanatory model for the shamans' actions at the time: The trances, ritual ecstasies, or "fits" of the shamans were not expressions of hysteria or obsession, he argued, but rather well-orchestrated, culturally coded performative solutions to conflict that were used, for example, against Russian foreign domination-that is, historically specific phenomena. In the Soviet Union, for example, shamans were denigrated as charlatans who allegedly tried to gain power with the help of religious rituals.

The "spirit men" or "magic men" of North America also repeatedly assumed the role of political leaders in the course of the white colonist's westward migration and placed themselves at the head of nativist movements. Thus, as early as 1680, a temporarily successful revolt of the Tewa in New Mexico against the Spanish colonists was organized by the medicine man El Popé. In African revolts against colonial rulers, spiritual mediators often played a role as leaders, such as the healer Kinjikitile Ngwale, allegedly possessed by the spirit Hongo of the snake god, in the Maji-Maji uprising of 1905-1907. Those who showed that they were possessed by a Hongo were able to influence the religion and politics of their ethnic group to a great extent. Lévi-Strauss also reports of shamans who competed with tribal leaders.

With the abandonment of the German Kulturkreislehre, which was frowned upon as racist, and the evolutionist "Stufen-Ideologie" in the Marxist-influenced states, a more respectful attitude toward the cultures of the so-called primitive peoples prevailed in ethnology.

In North America, already at the turn of the 20th century, there was a certain romanticization and idealization of the Indian cultures of North America and with them of the spiritual-religious ideas, which were soon combined with the ecstasy shamanism of Siberia and later also with the occult practices of South America up to those of the Selk'nam on Tierra del Fuego as shamanistic complex.

It was the Romanian religious scholar and novelist Mircea Eliade who in 1951 decisively coined the term "shamanism" and made it popular in academic and intellectual circles worldwide. Eliade saw in it the oldest form of the sacred, indeed the cross-cultural archetype of every occult tradition in general. His cultural-philosophical approach is considered today as very speculative and romanticizing.

In the late 1960s, the novelistic and ostensible self-experiential accounts of the American writer Carlos Castañeda sparked enormous interest among a mass audience almost worldwide. The focus of his work was on the archaic ecstasy technique preformulated by Eliade, which he hyped as a crucial feature of shamanic practices.

Around 1970, trance-induced spiritual practices became the subject of neurology for the first time, which looked more closely at the shamans' altered states of consciousness and/or their healing successes. Endorphins ("happiness hormones"), hypnosis or placebo effects through drum and dance rituals were used as explanations. As trance techniques are among other things possible: "monastic seclusion with sensory deprivation," fasting, sleep deprivation, litanies or repetitive verbal suggestion, dance with the side effect of hyperventilation, drugs such as Indian soma, Iranian haoma, Mongolian harmine, African iboga, Mexican mescaline, and psilocybin in Mexican peyote cactus (see peyote cactus cult), European henbane, fly agaric, hashish, alcohol, and East Asian opiates.

In 1980 Michael Harner's concept of core shamanism as a worldwide universal primal religion appeared. Many authors criticized such far-reaching generalizations and related their concepts again only to the classical Siberian shamans; or they clearly distanced themselves from the preponderance of spiritual aspects and examined, for example, cultural peculiarities, social functions or the healing significance of the necromancers in the different cultures.

Tuvan shaman: Traditional knowledge is distorted by neo-shamanistic influences

Mexican bald, the first popular "intoxicating mushroom".

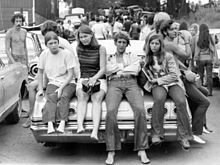

The hippie movement paved the way for a new spirituality in the West

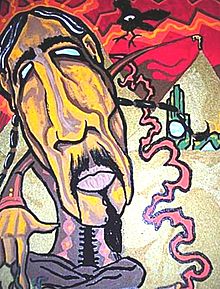

Fantasy portrait of literary shaman figure Don Juan Matus (Jacob Wayne Bryner), who made writer Castañeda world famous

Soviet ethnologists saw shamans as men who wanted to gain political power through religious rituals. In fact, there were female shamans as well, and sociopolitically, necromancers tended to be outside society.

Mircea Eliade is considered the founder of the "shamanism thesis", on which esoteric neo-shamanism in particular relies today. The validity of his theory and the seriousness of his work is strongly disputed in science.

Widely accepted theses

The classical Siberian shamanism or animism

"The [Siberian] shamanism is not only an archaic ecstasy technique, not only an early stage of development of religion, and not only a psychomental phenomenon, but a complex religious system. This system includes the faith that worships the auxiliary spirits of the shamans and the knowledge that guards the sacred texts (shamanic chants, prayers, hymns and legends). It includes the rules that guide the shaman in the acquisition of the ecstasy technique, and it requires knowledge of the objects needed in the séance for healing or divination. Generally, all of these elements occur together."

- Mihály Hoppál

The research of shaman traditions began with the small Siberian peoples and at the beginning of the 21st century it often comes back to it: Many authors use the term shamanism exclusively for the Siberian cultural area, but without naming it concretely; and although shamanism and religion are mostly no longer put into a primary context, the classical Siberian form (often only undifferentiatedly called shamanism) is not seldom used as a synonym for the animistic religions of Siberia and Central Asia because of its extensive research history

Decisive for the classical shamanism of Siberia is the homologous (originating from one root) emergence of its varieties through the historical cultural transfer from one ethnic group to the next or - according to Michael Witzel - through migratory movements of the ancient Asian peoples and their expansion across the Bering Strait. He points out that the distribution area of one of Y. E. Berezkin (2005), described by Witzel as "Laurasian" and dated to the Late Paleolithic, largely coincides with the distribution area of shamanism as well as with the distribution of the hypothetical Na-Dene language family and the C3 haplogroup of the Y chromosome.

Historical development

The presentation of the similarities between the beliefs, rites, cults and mythologies is hardly understandable without knowing the historical background of the peoples living there. Siberia was first settled about 20,000 to 25,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic until the Neolithic, when most of the entire area was inhabited. The first archaeologically verifiable cult sites were established a few thousand years ago. They already show a pronounced cultural differentiation of the peoples there.

In the steppes and forest steppes of southern Siberia lived peasant and pastoral peoples, while in the taiga adjoining to the north, hunting, fishing and gathering were the normal subsistence strategies. Especially the peoples in Yakutia and in the Baikal region had close relations to each other; archaeological artifacts such as rock paintings bear witness to this, allowing certain conclusions to be drawn about their religious beliefs. In the tundra and forest tundra of the far north lived predominantly small and relatively isolated peoples who either lived from sedentary fishing or hunting marine mammals or were semi-nomadic reindeer herders.

Until the 16th and 17th centuries, the peoples of Siberia still lived apart from European influences. For centuries, however, their beliefs were influenced by various religions from the Near East, Central Asia and East Asia. These included Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism and Christianity, and above all the influence of Buddhism. The proto-Mongol peoples had already come into contact with it from the 2nd century B.C. onwards. Mongolian tribes then brought Mahayana Buddhism to Central Asia as far as the Amur region between the 8th and 12th centuries. In the early 15th century, the Gelug school of classical Indian Buddhism was founded in Tibet and spread to Buryatia, Kalmykia and Tuva by the 17th century. By the end of the 19th century, Buddhism was established among the Trans-Baikal Buryats and influenced the daily life, culture, and outlook on life of many Siberian and Central Asian peoples. This led to a syncretic mixing of shamanic and Buddhist ideas. An example is the shaman mirror toli among the Buryats, which originally came from China, and the appearance of persons who were both lama and shaman.

Cosmology

→ Main article: Shamanic cosmology

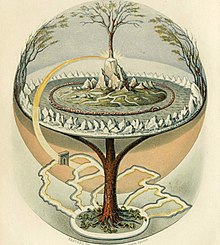

Part of the classical shamanic cosmology was the afterlife concept of a multi-layered cosmos consisting of three (sometimes more) levels: Benevolent and malevolent spirits exist in the upper and lower worlds, and a world axis (axis mundi) connects the three levels in the center. Depending on the culture, this axis is symbolized by the world tree, the smoke hole in the yurt, a sacred mountain or the shaman drum. The soul was considered an entity independent of the body, which can travel on this axis to the spirit world with the help of animal spirits.

The ritual ecstasy

The so-called "ritual ecstasy" was and is an essential element of classical shamanism, but also of all religious-spiritual shamanism concepts, some of which go far beyond Siberia. Depending on the illness of a patient, the wish of a group member or the mission of the community, the shaman went on a "soul journey into the world of the spirits" to make contact with them or to positively influence their work in the sense of the problem to be solved. As a rule, the natural balance between the worlds was considered disturbed in some way and it should be rebalanced in this way.

Such a spirit conjuration (séance) was a highly ritualized affair that required various measures and had to take place at the right time in the right place (→ Kamlanie, the séance of the Siberian shamans in the article "Séance").

The actual ecstasy is experienced, depending on the cultural imprint, either as the emergence of one's own soul or as possession by a spirit.

Hinaustreten (also passive or trophotropic ecstasy) - the classic and by far the most common type of ecstasy in Siberia - is described as a magical flight into another spaceless and timeless world, in which man and cosmos form a unity, so that answers and insights reveal themselves that would remain unattainable by normal means. Experiencing this inner dimension is distinctly real and highly conscious for the shaman.

In the imagination of traditional people, the experience of an afterlife journey corresponded to the dreams of ordinary people, but consciously induced and controlled; similar to a lucid dream. In the process, the shaman's vital functions sink to an abnormal minimum: shallow breathing, slow heartbeat, lower body temperature, rigid limbs and clouded senses characterize this state.

In complete contrast to this is the ritual ecstasy of (learned) possession (active or ergotropic ecstasy), which occurs in Siberia only among a few ethnic groups in the transitional areas to the high religions of Islam and Buddhism. In South and Southeast Asia or in Africa, on the other hand, such states of possession are the norm. The shaman has the feeling that a being from the Otherworld would enter him and take possession of his body for the duration of the ritual in order to solve the set task. This causes a strong increase in bodily functions: He gets into turmoil, raves, foams, fidgets or "floats", talks in incomprehensible languages and shows enormous strength.

In both forms of ritual ecstasy, altered perceptions occur, which can affect all sensory impressions (sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste, bodily sensation). In addition, the emotions, the experience of meaning and the sense of time are modified. The intensity of these impressions is much stronger, more unpredictable, and beyond the person's accumulated experience than, for example, in fantasy journeys that can be produced while awake.

From a neuropsychological point of view, in both cases a certain form of an extended state of consciousness is present, which is called "ecstatic trance". In all forms of deep trance, there is simultaneously a very deep relaxation as in deep sleep, the highest concentration as in awake consciousness, and a particularly impressive pictorial experience as in a dream. The special way in which the shamans of Siberia (but also of Central Asia, of northern North America, partly of East and Southeast Asia and of some peoples of the rest of America) induce the trance, as well as the cultural imprint and the corresponding religious orientation, leads in the shamanic trance through the neurological "hyper-state of rest" to passive or through "hyper-excitement" to active ecstasy.

The shaman always experiences this extraordinary mental state as a real event that seems to take place outside his mind. Sometimes he sees himself from the outside (out-of-body experience), similar to what is reported in near-death experiences. As is known today, man in this state has direct access to the unconscious: the hallucinated spirit beings arise from the instinctive archetypes of the human psyche; the ability to grasp connections intuitively - that is, without rational thought - is fully developed and often manifests itself in visions that are later interpreted against one's own religious background.

To achieve such states, certain formulas, ritual actions and mental techniques are used: These are, for example, burning incense, certain monotonous rhythms on special ceremonial drums or with rattles, dance (trance dance), chanting or special breathing techniques. The Siberian shamans usually do not need psychedelic drugs to achieve ecstasy as many other peoples do. Only the Uralic peoples sometimes use toadstools (for some authors, it is precisely the ability to trance without drugs that is a hallmark of classical shamanism).

Particularly important for achieving a non-drug-induced trance is the adoption of ritual postures (according to Felicitas Goodman) in conjunction with steady percussion rhythms in the range of 3.5 to 4.4 hertz (equals about 210 to 230 drum beats per minute). These frequencies correspond to the theta and delta brain waves that are otherwise typical of sleep or meditation. During trance, so-called "paradoxical arousal" states occur. Paradoxical because, on the one hand, they indicate a state that can be described as "more awake than awake" and, at the same time, show EEG curves that are otherwise known only from deep sleep stages. Subjects reported particularly impressive hallucinations during these trance phases. Furthermore, significant beta and delta increases are measured, which characterize a very deep relaxation and promote, among other things, physical healing reactions and memory processes. The paradoxical states of arousal discovered by Giselher Guttmann in 1990 thus indicate a "relaxed high tension". In general, the release of a special combination of different endogenous neurotransmitters is stimulated, which "open up" consciousness: perception is directed entirely toward inner content (intersensory coordination), the cognitive filters of the normal waking state are inactive, while the observing ego remains active.

Basically, all ritual trances produce either particularly passive or particularly active physiological effects, which then express themselves in the shamans in the two aforementioned forms of ecstasy. However, the more intense the respective ecstasy is, the less the intentionally induced hallucinations can be controlled.

The measurement of brain waves and the like. methods can only prove that consciousness is active in a certain way. However, no conclusions can be drawn about the concrete contents of the respective states of arousal. Therefore, it is in principle impossible to prove or disprove that the impressions in ritual ecstasy are imaginations or actual glimpses of an otherworldly world. This remains a matter of faith.

Müller: Elemental, complex and possession shamanism

For concrete description of the present situation and references see: Modern Shamans in the Light of History in the article "Shaman".

"Apart from all secondary additions, shamanism represents at its core a visibly very old and optimally adapted to the conditions of existence of savage and field-herding cultures, that is, apparently `proven' and insofar stable over long periods of time, as coherent as it is coherent, as it were `unified' theory of being and nature."

- Klaus E. Müller

In 1997, the German ethnologist Klaus E. Müller presented an approach that describes shamanism as a kind of "science of magical-mythical thinking" that was developed, transmitted and preserved by "appointed experts" with important social obligations. Müller recognizes the similarities regarding religious views or ritual trance techniques, but explicitly distances himself from considering such "spiritualistic and occultistic aspects" as defining characteristics.

Müller continues Adolf E. Jensen's thoughts, who saw shamanism as a typical phenomenon for hunter cultures, which in principle regarded animals as their relatives. Clear indications of this assumption are the manifold totemic animal references: The calling of the shamans took place through the "animal mother" in the spirit world or the "lord of the animals", the auxiliary spirits were predominantly animal-shaped, the shaman - often dressed with animal attributes - often transformed into a spirit animal on the journey, the magic drum or mallet was taken as a symbolic mount for the journey and some more.

According to Müller, the original form of shamanism is primarily a ritual for forgiveness and averting punishment and disaster when a hunter disregarded the traditional appeasement and binding rituals for killing an animal. This played a central role in everyday life for all hunter peoples and ultimately served to safeguard animal and plant populations.

According to him, shamanism originated somewhere in Asia in the Upper Paleolithic period clearly before 4000 B.C. and spread from there in many centuries among the "soulmate" hunter peoples over the entire Asian continent and beyond to North, Central and South America as well as to Australia. Based on the description of the shaman as "expert and mediator to the spirit world" and the resulting social obligations, a corresponding distribution map of shamanism can be drawn.

In Müller's view, the "classical" area includes not only Siberia, but also present-day Kazakhstan and scattered local communities in Southeast Asia, including the Indonesian archipelago. Sometimes he also mentions the shamanism of the Eskimo peoples of North America in this context. However, it is not clear whether he actually includes them in classical shamanism or not. According to Müller, the shamanism forms of the Aborigines and the Indian peoples have split off early from the classical elementary forms and have further developed isolated. In contrast, Witzel considers Siberian shamanism to be a relatively "young" split-off (at least 20,000 years old) from a more widespread paleo-shamanism.

Müller considers it likely that the original ("elemental") shamanism of hunter-gatherers in the subpolar regions of Asia and North America has survived largely unchanged into modern times because the environmental and living conditions there have remained virtually the same. Moreover, he notes that to this day it is found primarily among ethnic groups that have a close relationship with the animal kingdom (wild-herder and pastoralist cultures, as well as the garden and shifting-field farmers of Amazonia, whose way of life has a strong "hunter-gatherer" component). In pure planter cultures or among agropastoralists, shamanism has always played only a marginal role.

Klaus E. Müller therefore derives his forms of shamanism primarily from their socio-economic bases and from this he developed a three-part classification model (the following descriptions of which are written in the past tense, since today they apply only selectively to a few isolated peoples):

Elemental Shamanism

Color scheme:

- Emergence:

Elemental (primary) shamanism was typical of pure hunter cultures or of ethnic groups in which hunting played a prominent cultural role.

- Characteristics:

The social basis is based on egalitarian local communities or kinship groups (lineages, clans). The ethnic religions were usually animistic. The shaman was predominantly male. Believed to be called by animal spirits, he was primarily responsible for hunting success or adherence to "hunting ethics," but also acted as a healer and monitored the reproductive success of the group. The ritual was not very pronounced and costumes or special aids hardly occurred or only sporadically and in a simple form.

- Distribution

1. classical asian cultural area

· Unique shape:

Original nomadic to sedentary hunter-fisher-gatherers of northern and eastern Siberia; since Russification, often reindeer herders like the other Siberian peoples. Variants from the historical differentiation:

Paleo-Siberian (primary) savage tribesmen (Chukchi, Yukagirs, Koryaks, Itelmen)

Siberian (secondary) wild boars (Nganasans, Dolganes, Keten)

In northeastern India among a few groups (attenuated) especially in the central area (e.g., Birhor), scattered hunter-gatherers of Southeast Asia (Derung, Yao, Akha, Mani, Orang Asli peoples, Sentinelese, Shompen, Mentawai, Kubu, Penan, Batak, Aeta).

2. America and Australia

· Unique (classic?) form:

Nomadic to sedentary hunter-gatherers of the Arctic of North America (Eskimos and Aleuts)

· Unique shape:

Nomadic to semi-settled hunter-gatherers of the subarctic (Athabascans, Algonkin) and settled fishermen of the northwest coast

· Restricted form:

Nomadic to sedentary hunter-gatherers (partly field farmers) of the "Wild West" (Plains Indians and Indians of the Plateau, Great Basin and California cultural areas)

Nomadic hunters & gatherers of South America of the South American cultural areas Llanos, Paraná and Tierra del Fuego

· Variable shape, not continuous:

Nomadic hunter-gatherers of the Aborigines, not continuous (especially in the Western Desert as well as in Northern Australia)

Complex Shamanism

Color scheme:

- Emergence:

The secondary complex shamanism has arisen among pastoral peoples and field farmers with a significant share of wild beasts in Asia as well as in America presumably by manifold influences of neighboring agrarian societies and by contacts with other religions - according to Witzel by substitution of the animal deities by plant and vegetation gods (e.g. corn gods like Cinteotl.).

- Characteristics:

The social basis is formed by kinship associations, tribal societies or autonomous village communities. The animistic religions were more complex (for example, with ancestor worship, sacrificial beings, and a complicated cosmology). The calling of shamans was attributed to ancestral spirits or the dead souls of former shamans (the latter especially among Tungus and groups in the Altai Mountains), or shaman status was inherited from father to son or mother to daughter. There were predominantly male shamans, although female shamans also appeared more frequently. The functions and techniques of the shamans corresponded on the one hand to elemental shamanism, but in addition there were also priestly, communal and domestic-family functions (for example at births, naming, burials, initiations). Rites, costumes with extensive accessories (such as metal) and utensils were often complex and of great importance. Entheogenic drugs were also frequently used to achieve the trance.

- Dissemination:

1. classical asian cultural area

· Pastoral nomads. Variants from the historical differentiation:

Western Siberian reindeer herders (e.g. Sámi, Nenets, Khanty, Mansi)

Central Siberian Reindeer Herders (Tungusic Peoples)

Altai reindeer and horse breeders (e.g. Kazakhs, Tuvins, Yakuts)

Manchurian fishermen (e.g. Tungusic peoples of Manchuria, Niwchen, Ainu)

· Tropical/subtropical plant communities, not continuous, sporadic.

Local minorities of Hind India (e.g. Naga, Aimol, Moken, Jakun, Senoi) and Indonesia (e.g. Dusun, Halmahera)

2. america

· Differentiated forms, partly not continuous:

North America's Northeast, (e.g., Shawnee, Iroquois, Sauk, Powhatan).

Mexico (e.g. Tarahumara, Huichol)

Meso- and South America (all plant communities outside the high Andes).

Possession Shamanism

Color scheme:

- Emergence:

High-culture syncretic possession shamanism can be traced back to influences of archaic high cultures, Asian high religions (especially Buddhism) and to the fusion with possession cults.

- Characteristics:

The usual social base was the peasant village community. The religious orientation consisted of an official direction - such as Islam, Lamaism, Vajrayana Buddhism, Hinduism, Shintoism, etc. - and a syncretic folk faith that fused elements of the high religions and the old traditional beliefs. Women who felt called to do so were more often shamans here than men. They felt bound for life to a spirit power or deity to whom sacrifices and homage were regularly paid in small temples set up for the purpose. The shaman's duties were the same as those of complex shamanism and were primarily directed toward medical services as well as counseling and divination. In contrast to the other forms of shamanism, there was no "journey to the other world" by means of a ritual ecstasy, but the shaman had the impression during the trance that her personal partner spirit would take possession of her; "drive into" her and heal, prophesy, etc. with the greatest of ease. In contrast to other - according to Müller non-shamanistic - possession cults of other cultures (for example of Africa or New Guinea) the entering of the spirit took place on invitation of the shaman and not "abruptly" or against the will of the person concerned.

In the Islamic contact area today, the influence of the old religions is much less noticeable than in the Buddhist contact area.

- Distribution

· Asian culture area

Especially in sedentary peasant village societies

Islamic sphere of influence (e.g., Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kyrgyz, Uyghurs)

Lamaist sphere of influence (e.g. Buryats, Mongols, Yugur, Tibetans, Changpa, partly Nepalese)

Buddhist-Daoist sphere of influence (e.g., majority populations of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, rear India).

Criticism

Although Müller includes various cultural aspects in his way of looking at things and his "three-type model" certainly makes differentiations, his "standardization" also sometimes leads to questionable results due to the global scale. For example, René Tecklenburg states that the shamanism of the Lakota Indians cannot simply be assigned to elemental shamanism, since it also shows clear characteristics of the peasant type (close connection to the guardian spirit, numerous cult objects, complex ceremonies and rituals, sacrifices, etc.).

Holistic medicine

Modern theses often focus reductionistically on a certain sub-area of shamanism: for example on the psychological or neurobiological aspects or on healing, but the cultural background is left out.

Often shamanism is understood today only as a special form of traditional healing methods. Ronald Hitzler, Peter Gross and Anne Honer, for example, describe it as "a complex, integrative social art that embeds the competence to heal, in the medical sense, in the concern for and service to the existential 'healing' of fellow human beings in general." They thus attest to the shamanic healing rituals a holism that is no longer present in modern medicine. Instead of impersonal "repair services at the treatment object" of physicians, who would understand no more much from health, but for it all the more from illness, the shamanism is characterized by empathy, mutual communication and mitmenschliche care, which has beyond the well-being of the patient even the well-being and woe of the entire community in the sense. For Hitzler, Gross, and Honer, moreover, shamanism is "a way of man's universal-historical efforts to gain mastery, through knowledge, over the powers within him that seem unfathomable to everyday understanding."

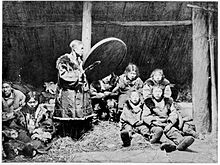

Shaman of the Jukagirs (Northeast Siberia, 1902)

Northwest Coast Indian Shaman

Shamans as "experts and mediators to the spirit world" according to Klaus E. Müller before the European expansion, which began in the 15th century (colored areas); as well as traditional shamans and other religious-spiritual specialists at the beginning of the 21st century, who still hold various social functions (black and white symbols/hatching)

| Elemental Shamanism | Complex Shamanism | Possession Shamanism |

| Classic (primary), Arctic peoples | Classic West Siberian | Islamic sphere of influence |

| colored circle symbols: |

|

| Isolated ethnic groups with completely preserved social functions of their religious-spiritual specialists |

|

| Isolated ethnic groups of New Guinea with traditional religions, but without knowledge of shamans or similar. Necromancers |

|

| Local communities with largely intact traditional structures in which necromancers still perform some of their original functions. However, their functions have already been more or less influenced by modern influences. |

|

| Traditional societies with largely intact structures where necromancers still perform some of their original functions (distribution density depending on hatching/area fill). |

|

| Traditionally integrated into states and/or other religions "city shamans" of East and Southeast Asia |

Lakota medicine man Sitting Bull: complex shamanism like in Asia?

Stone Age cave painting in Les trois frères cave with hunter context: "Lord of the animals" or shaman?

The living conditions of the Arctic peoples have hardly changed over thousands of years, so that, according to Müller's assumption, the shamanism there has hardly changed at all

The world according to the Germanic mythology corresponds approximately to the classical Siberian cosmology of the three worlds. The Indian stupa is also one third underground.

African sangoma medicine man dances in obsessive state

Percussion rhythms with drums or rattles are crucial for ecstatic states

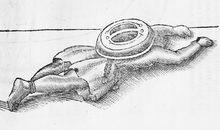

Lying sámic shaman: Ritual postures lead faster to trance

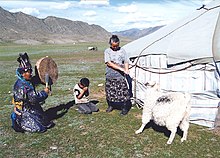

Shamanic ritual in the Siberian steppe

Also the reindeer herding Sámi of Northern Europe used to have shamans belonging to the Siberian type

Modern Buryat shaman with ritual staff

.PNG)

Distribution of haplogrupo C3

Shaman from Altai Mountains (between 1911 and 1914)

Tantric Buddhism and Shamanism are merged among Mongolian peoples

Shaman of the Urarina from Peru

_healing_a_sick_woman._-_NARA_-_297728.jpg)

Shaman from Alaska during a healing ceremony

See also

![]() Topic Lists: Religious Anthropology + Ethnomedicine - Overviews in Portal:Ethnology

Topic Lists: Religious Anthropology + Ethnomedicine - Overviews in Portal:Ethnology

- Mongolian Shamanism

- Shamanism in Korea

- Shamanism in Japan

- Wuism (former classical shamanism of China)

- Animalism (religious attachment to animate animals)

- Animatism (sees inanimate things of nature as alive).

- Fetishism (Religion)

- Archaic Spirituality in Systematized Religions

Search within the encyclopedia