Shaman

![]()

This article is about the person - for the novel see The Shaman.

The term shaman originally comes from the Tungusic peoples, šaman in the Manchu-Tungusic language means "someone who knows" and denotes a special bearer of knowledge. Among the Siberian and Mongolian Evenks the word šamán has a similar meaning. In German, the term shaman, borrowed by travellers from Siberia, became widespread at the end of the 17th century and is used in two different readings, which can be derived from the respective context:

- In the narrower, original sense, shamans are exclusively the spiritual specialists of the ethnic groups of the cultural area of Siberia (Nenets, Yakuts, Altai, Buryats, Evenks, also European Sámi, etc.), among whom the presence of shamans was considered by European researchers of the expansion period as the most essential common characteristic.

- In a broader, frequently used sense, the term shaman serves as a collective term for very different spiritual, religious, healing or ritual specialists who function as mediators to the spirit world among the most diverse ethnic groups worldwide and to whom corresponding magical abilities are attributed. In most parts of the world, they use this in the sense of cultic and/or medicinal acts for the benefit of the community. To this end, they engage in various mental practices and rituals (sometimes with the use of drugs), which are intended to expand normal sensory perception in order to be able to make contact with the "powers of the transcendent beyond" for various reasons. In this context also the medicine man (in the original and narrower sense the "companion and advisor of North American Indians for the handling of their medicine, the power from the contact with spiritual and natural beings", in the broader sense healer from traditional cultures) or the medicine woman of American or Australian tribes is called shaman. Furthermore, so-called spirit charmers from Africa or Melanesia (various sorcerers, healers, fortune tellers, etc.) - who, in contrast to the "all-round specialists" of the other continents, each cover only a few tasks - are also sometimes called shamans.

The very generalizing and undifferentiated use of this designation for the religious-spiritual specialists of non-Siberian ethnic groups (as is common in the context of so-called shamanism concepts) is criticized by some scholars and indigenous peoples because it suggests an equality of very different cultural phenomena. They plead for using the respective regional designations instead.

Various spirit charmers, regardless of gender, are or were actors in very many ethnic religions, but are also found in some folk-religious manifestations of world religions, such as Buddhist and Islamic cultures. In particular, they continue to play a role in some traditional indigenous communities today - although often in a significantly weakened and modified form. The existence of ritual experts probably goes back at least to the magical-spiritual religiosity of the Middle Stone Age. However, the interpretation of corresponding finds is disputed (→ Prehistoric shamanism).

In the past, in most regions, such people were part-time specialists who otherwise pursued other forms of subsistence. Modern "neo-shamans" (who will only be discussed in passing in this article), on the other hand, are often full-time specialists who actively offer their activities and make a living from them.

.jpg)

Siberia: Chuonnasuan (1927-2000), the last shaman of the small Tungusic Oroken people (1994).

Problem of demarcation; example shaman and priest

As early as the 19th century, the originally Tungusic-Siberian term was applied to similar spiritual experts of other cultures. Many authors who published on concepts of shamanism expanded the term even further. This development has led to ignoring cultural differences in favor of a generalizing account, suggesting that there are shamans worldwide in a unified sense. This is a fallacy that is also denounced by members of different ethnic groups.

For example, the Navajo medicine man called Hataalii is more of a priest and artist: an expert in religion, music, some (not all) ceremonies, and the art of sand paintings. The Sioux peoples also did not and do not have shamans in the strict sense. Since the commercialization of their spiritual traditions by neo-shamanism, they vehemently distance themselves against this designation and the abuse by "white shamans".

The fact that among some North American tribes all people went on vision quests and there was no separate expert for it, or that certain hallucinogenic drugs (called entheogens) in South America make almost anyone a shaman, was also ignored in many concepts.

On closer examination, there are numerous examples of so-called shamans who should in fact rather be called priests, healers, sorcerers, wizards, and so on. Some anthropologists have therefore proposed to use only the indigenous designations for the respective persons in order to end the egalitarianism.

The distinction between shamans and priests, as proposed by the missiologist Paul Hiebert in his "Typology of Religious Practitioners", is a suitable way of illustrating the problem. On the basis of such schemes it can then be determined to which category a concrete specialist is actually to be assigned. However, the transitions are fluid and therefore even such a determination remains model-like. The following table should be preceded by the fact that traditional spirit conjurers had other secular functions depending on their cultural affiliation, since traditional ethnic groups often had no separation between everyday life and religion.

| Shaman | Priest | |

| Legitimation | Calling by spirits | Appointment by religious institution, profession |

| Authority | Charisma and gift | invested dignity |

| Tasks/Motivation | Mediation to the transcendent, preservation of tradition | Management of religious cult, preservation of tradition |

| Basic activity | makes contact with the transcendent powers for the benefit of the community or individuals | approaches the transcendent powers on behalf of the community... |

| Remuneration | in former times no consideration for services to the common good, rarely for private orders as healer or fortune teller | regulated forms of different types of remuneration |

| Cult | culturally transmitted, but variable | systematic, fixed |

| Relationship to religion | independent of local religion; influence on faith possible | dependent on the religion represented; no influence on doctrine |

| Status | independent, respected advisor by virtue of his skills | attendant |

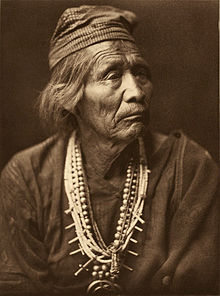

Nesjaja Hatali, "Medicine Man" of the Navajo - Priest and Artist (Edward Curtis, 1907)

Traditional priest (Bobohizan) of the Dusun people from Sabah - no shaman

Etymology

The German word "Schamane" - which can be traced in Germany since the end of the 17th century - as well as the corresponding words in many other European languages (English, Dutch, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian: Shaman, Finnish: Shamaani, French: Chaman, Italian: Sciamano, Latvian: Šamanis, Polish: Szaman, Portuguese: Xamã, Russian: Šamán, Spanish: Chamán or Hungarian: Sámán) are mostly regarded as loan words from the Tungusic languages, which, with the Evenkian "Šaman", corresponds most closely phonetically to the derived European forms. The word is present in all Tungusic idioms in the meaning of "one who is excited, moved, uplifted" or also "lashing out", "mad" or "burning". All these translations refer to the bodily movements and gestures performed by Siberian shamans during ecstasy. However, a connection with the verb sa, which means "to know, to think, to comprehend," is also possible. Accordingly, Šamán could be interpreted as "knower".

More rarely, "shaman" is etymologically traced back to the Indian Pali word "śamana", which means "mendicant monk" or "ascetic". In this context, some authors suspect an older Indian Buddhist root, which would in turn make the Tungusic word a loanword adopted by Buddhist Tungus as a term for "pagan sorcerer-priests". Friedrich Schlegel was the first to include Sanskrit in the etymology.

Finally, some authors trace the word to the Chinese sha-men for witch.

In the Turkic-speaking regions of Tuva, Khakassia and Altai, shamans refer to themselves as kham (khami, gam, cham). The shamanic songs are called kham-naar. In the course of the Islamization of the Central Asian south, bakshi (from Sanskr. bhikshu) replaced the native term kham among many Turkic peoples as a generic term for pre-Islamic religious specialists. Numerous other terms for the person of the shaman were regional. (The word kham may be related to the concept of kami-spirits or -gods, central to Japanese - still strongly shamanic - Shintoism). Instead of the Tungusic Šaman, Mongolian uses the expressions böö (masculine or gender-neutral) and zairan (masculine, or title for "great" shamans) and udagan for shamaness.

With regard to the Indians of North America, the term medicine is used divergently for the "mysterious, transcendent power behind all visible phenomena" (→ medicine bag or medicine wheel). The term medicine man here is in fact a literal translation of corresponding terms from various indigenous languages (such as Pejuta Wicaša in Lakota).

The earliest known depiction of a Siberian shaman was by the Dutch explorer Nicolaes Witsen, who made an expedition through Russia in 1692; he called the illustration "Priest of the Devil"

Search within the encyclopedia