Shakespeare authorship question

William-Shakespeare Authorship deals with the debate that has been going on since the 18th century as to whether the works attributed to William Shakespeare (1564-1616) of Stratford-upon-Avon were in fact written by another author or by multiple authors.

Doubters of William Shakespeare's authorship argue that there is a lack of concrete evidence that the Stratford actor and businessman was also responsible for the literary work that bears his name. They say there are all too many gaps in the historical record of his life and that no letter written to him or by him has survived or is known to exist. His detailed will makes no mention of any of the business interests he held in the Globe and Blackfriars Theatres, nor does it mention any books, plays, poems or other writings by his hand.

Indeed, almost nothing is known about his personality, and although some things about the historical figure may be indirectly inferable from his plays, he remains an enigmatic figure due to a lack of solid life-world information about himself. John Michell noted in Who Wrote Shakespeare (1996) that "the known facts about Shakespeare's life ... could be written down on a sheet of paper." He also quoted Mark Twain's satirical commentary on it in Is Shakespeare dead? (1909).

Literary scholars do not consider this lack of information surprising, given the distant lifespan and the generally patchy documentation on the lives of non-noble or non-upper class people from the period, especially those from the Elizabethan theatre. As a result, the debate does not play a significant role in serious literary scholarship. Stephen Greenblatt, one of Shakespeare's leading experts, wrote in 2005, for example, that there was an "overwhelming scholarly consensus" on the authorship question.

Another often mentioned reason for doubt is the general education that the author must have had, documented above all by the enormous vocabulary of about 29,000 different words, almost six times as many as in the King James Bible, which gets by with 5,000 different words. Many critics find it difficult to convince themselves that a sixteenth-century person from a social class below the high aristocracy with Shakespeare's historically recognizable schooling could have been so versed in English, or even in foreign languages, recognizable primarily by the fact that the works contain specialized vocabulary from the fields of politics, jurisprudence, or horticulture, for example. There is no evidence that he attended at least a grammar school or even a university. Doubting whether, from the available information on Shakespeare's life, the historical Stratford theatrical man Shakespeare was capable of writing the works attributed to him, other more suitable persons of the time period are considered as more likely authors of Shakespeare's works. Shakespeare would therefore have been only a kind of "frontman" for the real author, who wanted (or needed) to remain anonymous.

For nearly 200 years Francis Bacon was the leading alternative candidate. In addition, several other candidates were suggested, including Christopher Marlowe, William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. The latter was the most popular candidate among antistratfordians in the 20th century as the eventual author of Shakespeare's works. Although all theories for alternative candidates have been dismissed by classical literary scholars to date, interest in the authorship debate has increased, especially among independent scholars, theatre professionals, and non-philologists (for example, Friedrich Nietzsche, Otto von Bismarck, and Sigmund Freud are among the better-known doubters), a trend that continues into the 21st century.

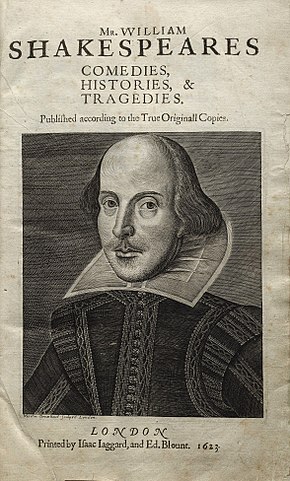

Front of the so-called First Folio (1623), titled "the first collected edition of Shakespeare's plays". The "Folio" edition with its portrait plays a considerable role in the debate about authorship. The engraving is usually attributed to Martin Droeshout the Younger. Since the latter, born in 1601, was only fourteen at the time of William Shakespeare's death in 1616, seven years before the Folio edition was published, and therefore probably did not personally know the playwright himself, doubters of authorship have also questioned the circumstances of the Shakespeare work's creation, as well as Ben Jonson's assurance that the engraving is "true to life." Stratfordians reply that it has long been assumed that Droeshout started from a model, a "sketch". Charlton Ogburn, author of The Mysterious William Shakespeare (1984), noted that the curved line running from ear to chin makes the face appear more like a "mask" than a true representation of an actual person, while art historians see nothing unusual in this feature.

Terminology

"Anti-Stratfordian"

Those who doubt William Shakespeare of Stratford as the author of Shakespeare's works usually call themselves "anti-Stratfordians." Those who regard Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, or the Earl of Oxford as the principal author of Shakespeare's plays are usually called Baconians, Marlowians, or Oxfordians.

"Shakspere" versus "Shakespeare."

In Elizabethan England there was no standardized orthography, certainly not of a proper name, which is why during Shakespeare's lifetime one encounters his name in a wide variety of phonetic spellings (including "Shakespeare"). Anti-Stratfordians usually refer to the Stratford man as "Shakspere" (as his name appears in the baptismal and death records) or as "Shaksper", to distinguish him from the author of the work "Shakespeare" or "Shake-speare".

Anti-Stratfordians also point out that the vast majority of contemporary references to the Stratford man in public documents usually spell him in the first syllable without an "e" as "Shak," or occasionally as "Shag" or "Shax," while the playwright is consistently spelled with a long "a" as "Shake." Stratfordians, meanwhile, doubt that the Stratford man spelled his name any differently than the editors of the books. Since these so-called "Shakspere" conventions are controversial, the name will always be spelled "Shakespeare" in this article.

The idea of a secret authorship in Renaissance England

"Anti-Stratfordians" point to examples of anonymous or pseudonymous publications by Elizabethan contemporaries of high social rank in support of the possibility that Shakespeare was a straw man. In his description of contemporary writers and playwrights, Robert Greene wrote that "Others...if they come to write or publish anything in print, it is either distilled out of ballets [ballads] or borrowed of theological poets which, for their calling and gravity, being loth to have any profane pamphlets pass under their hand, get some other Batillus to set his name to their verses." ("With others, when they write or have anything printed, it is either drawn from ballads or borrowed from theological poets, who, for their calling and gravity, being loth to have any profane pamphlets printed under their name, get some other Bathyllus to put his name to their verses.") Bathyllus was known to have passed off verses of Virgil to the Emperor Augustus as his own. Roger Ascham, in his book The Schoolmaster, discusses the belief that two plays attributed to the Roman playwright Terence were secretly written by "worthy Scipio, and wise Lælius" because the language was too sublime to have been written by a "servile stranger" (Terence was from Carthage and came to Rome as a slave, his African name is unknown) like Terence.

Search within the encyclopedia