Shabbat

![]()

Shabat is a redirect to this article. For the Israeli singer of oriental music, see Schlomi Shabat, for the physicist Alexei Borisovich Shabat.

![]()

This article describes the seventh day of the week in Judaism. For other meanings, see Sabbath (disambiguation).

Shabbat (Hebrew: שַבָּת [ʃaˈbat], plural: שַבָּתוֹת [ʃabaˈtɔt] Shabbatot, also Germanised Sabbath in Christianity) is the seventh day of the week in Judaism, a day of rest on which no work is to be done. Its observance is one of the Ten Commandments (Ex 20:8 EU; Deut 5:12 EU). It begins on the previous evening and lasts from sunset on Friday until darkness falls on the following Saturday, because in the Jewish calendar the day lasts from the previous evening until the evening of the day - not from 0 to 24. This is derived from the 1st Book of Moses, Hebrew בְּרֵאשִׁית Bereshit, Ancient Greek Γένεσις Génesis called: "and there was evening and there was morning, one day". The evening beginning is designated by the word Erev (Hebrew ערב "evening"). Shabbat already has its own name in the Tanakh, while the other days of the week in the Jewish calendar are still named with their ordinal numbers. Jews wish for a peaceful Shabbat with the greeting שַבָּת שָׁלוֹם Shabbat Shalom.

"The 24-hour day, which is authoritative for civil life in Israel as a simplified measure of time, begins" at 6:00 p.m. the previous evening, regardless of sunset, but this does not comply with halakhic regulations. This was particularly necessary for international commercial traffic. Accordingly, Shabbat in the simplified time measure ends at 6 p.m. on Saturday.

The traditional Jewish Shabbat celebration begins on Friday evening at home with the Shabbat blessing (Kiddush) and a feast. The evening begins "when you can no longer tell a grey thread of wool from a blue one".

On Saturday morning, a service with Torah readings and prayers takes place in the synagogue, including a festive Torah procession. At home, further scripture readings and the mincha prayer follow at noon, and in the evening, at the light of the havdala candle, another blessing of the wine and the mutual wish for a "good week". The Shabbatot are named after the passages from the Torah (parashot) that are read weekly in the synagogue. The day is also said to be marked by the fact that three meals are eaten on it - one on Friday evening, two on Saturday - which meant opulence, especially for the poorer people of earlier times. So care is also taken to eat particularly well and festively on Shabbat. All in all, these strict Shabbat laws, if observed, lead to a lot of time for family, friends and spiritual activities due to the omission of all work, but also of classical leisure activities.

Orthodox Jews do not perform any activities on Shabbat that are defined as work (Hebrew מלאכה Melacha) according to the Halacha. The 39 melachot Hebrew ל״ט אבות מלאכה lamed tet avot melacha (39 types of work) originally refer to the activities, which were necessary for the construction of the Mishkan, the Tent of Meeting (אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד ohel mō'ēd), which the Jews carried with them on their desert wanderings. The melachot have become general principles that are applied to all areas of life. This results, for example, in the prohibition of lighting fires, which includes the operation of any electrical device, or the prohibition of carrying objects (cf. also muktza). Conservative Jews follow some halakhic Shabbat commandments less strictly. Reform, Liberal and Progressive Jews observe mainly ethical commandments and leave the observance of ritual regulations to individual responsibility. Reconstructionists do the same, but place greater emphasis on traditions.

In Christianity, the celebration of Sunday originated from the Jewish Shabbat. The weekly day of rest was placed on the "first day of the week", on which, according to Mark 16:2 EU, the resurrection of Jesus Christ took place. The breaking of bread in the early Jerusalem church (Acts 2:42 EU), which resulted from the Lord's Supper, was based on the Jewish Shabbat and Seder meal. The early Christians kept the Shabbat rest alongside their Sunday observance, as did many later Jewish Christians and some Gentile Christians (until about 400). Some Christian denominations keep the Shabbat to this day. For example, the Sabbath is observed by the Seventh-day Adventists, a Protestant free church, where it is also described. Unlike the Christian division of chapters, where a new chapter begins here, marking the conclusion of the act of creation, the Jewish division of texts according to reading units integrates the act of creation in the Torah reading and celebrates it as its climax.

In Islam, Friday prayer is loosely based (no general rest from work) on the celebration of Shabbat.

Shabbat candles

Erev Shabbat - Beginning of Shabbat - after the painting of the same name by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim. The Garden Arbour 1867

Tanakh

Shabbat texts of the Torah

The first creation story (Gen 1:1-2:4a) aims at God's rest after his six-day work (Gen 2:2f. EU):

| Hexaemeron | ||

| Hebrew | Transliteration | Translation |

| וַיְכַל אֱלֹהִים בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי, מְלַאכְתּוֹ אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה; וַיִּשְׁבֹּת בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי, מִכָּל-מְלַאכְתּוֹ אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה. וַיְבָרֶךְ אֱלֹהִים אֶת-יוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי, וַיְקַדֵּשׁ אֹתוֹ: כִּי בוֹ שָׁבַת מִכָּל-מְלַאכְתּוֹ, אֲשֶׁר-בָּרָא אֱלֹהִים לַעֲשׂוֹת. | Va-y'chal Elohim ba-jom ha-shvi'i m'lachto ascher asah, va-yischbot ba-jom ha-shvi'i mi-kol-m'lachto ascher asah, va-y'varech Elohim et yom ha-shvi'i, va-y'kadesch oto, ki vo schavat mi-kol-m'lachto, ascher bara Elohim la'asot. | On the seventh day God finished the work that he had created, and he rested on the seventh day after he had finished all his work. And God blessed the seventh day and declared it holy, for on it God rested after he had finished all the work of creation. |

This unnamed day is not linked to any commandment, but the verbs שבת (rest), ברך pi. (bless), לְקַדֵשׁ pi. (sanctify) and the noun מְלָאכָה [mlaˈxa] (work) are understood as allusions to the Shabbat commandment Ex 20:9-11 EU. From this it is concluded that both texts are by the same authors and that Shabbat already existed when they were written. They are often attributed to a hypothetical priestly scripture written during the Babylonian exile. The prehistory as a whole (Gen 1-11) is considered by scholars to be one of the most recent parts of the Pentateuch, and to have preceded the narratives of the Fathers only during the final editing of the Pentateuch.

According to Ex 16:16-30 EU, God gave the Jews the miraculous food manna for food every week for six days after their exodus from Egypt during their forty years of wandering in the desert. This could not be stored, but on every sixth day it was doubled and preserved, and on every seventh day it could not be found, so that no food could and had to be gathered on it. This day is here called for the first time in the Torah "holiday, holy Shabbat to the glory of the Lord" (v.23).

Martin Noth saw in Ex 16:19f EU the oldest text layer that he assigned to the Yahwist and the oldest biblical evidence for the rhythm of the week in the alternation of six working days and a seventh day of rest. The seventh day was prepared the day before as a work-free celebration, not celebrated with fasting, and justified as a gift from God in his saving action for the chosen people. The prohibition of food gathering and the commandment of general rest (v.28f.) is regarded as a later Deuteronomic addition, which should relate the text to Ex 15:25f.

Traditional Jewish exegesis links the Shabbat practice of the Jews according to Ex 16 EU with God's creative will: God drove man out of paradise and ordered him to work hard and sweat to earn his living (Gen 3:17ff.). He only exempted the Israelites from this in the desert time and cared for them for forty years as he did for Adam and Eve, in order to renew the original order of creation in an exemplary way until Israel found its promised land. The following Shabbat commandments revealed on Mount Sinai are also understood under this premise: The regular Shabbat, independent of nature, praises God's dominion over time and nature. By imitating God's rest with his rest, the Israelite acknowledges God's creative power and allows it to rule over his lifetime.

Shabbat commandments

The oldest commandment versions are social provisions in the Book of the Covenant that are linked to a seven-day or seven-year rhythm: According to Ex 21:2-6 EU, Hebrew slaves are to be allowed to choose every seventh year between freedom and remaining in the previous slave-owning family. According to Ex 23:11f. EU, the harvest is to be given to the poor and wild animals every seventh year. Shabbat is to be kept "so that your ox and your donkey may rest, and the son of your slave woman and the stranger may catch their breath". Ex 34:21 EU demands the observance of the day of rest especially during the labour-intensive harvest time in the cultivated land. This day of rest, which is not yet called Shabbat, may have originated from the peasant festival of matzos after the settling of the land or already in nomadic times.

Of all the Jewish festivals and rites, only Shabbat was included in the Ten Commandments. The commandment (Ex 20:8-11 EU) to "sanctify" it follows the commandment to sanctify the name of God, YHWH, and thus requires a cultic observance: for the Shabbat belongs to the God of Israel and is His commandment. He himself rested on the seventh day of creation, blessed the Shabbat and declared it holy. Thus this day becomes a special sign of the covenant and an act of confession by the chosen people in contrast to other peoples with other gods. The prohibition of work is formulated in general terms, but in the context of activities for the acquisition of food. It is prior to the commandment to work on the other six days. Thus, the day of rest appears as the goal and reason for each working week. It is offered to all members of a Jewish "household": Family members, servants, maids, domestic animals and foreign wage labourers living on their own land. Here the Deuteronomic version adds Dt 5:12-15 EU ox and donkey, slaves and female slaves, thus emphasising the social and animal protection aspect. The woman is not mentioned because she does not belong to the dependent labourers. The creation-theological justification is missing, instead the commandment is justified here with Israel's memory of slavery in Egypt, from which God's mighty hand had led his people out.

Most versions dating to the late royal period (700-586 BC) emphasise the cultic aspect: Lev 23:3 EU enjoins Jews, wherever they are, to worship on the day of rest. Lev 26:2 EU requires the keeping of the holiday in connection with respect for the sanctuary of the time, the Jerusalem Temple. Ex 31:12-17 EU emphasises the unconditional validity of the Shabbat commandment for all Israelites in the context of God's final speech to Moses on Mount Sinai:

"Only keep my Shabbat! For this is a sign between me and you for all your generations, that you may know that I am the LORD who sanctifies you."

It makes visible the "eternal covenant" between God and Israel and thus serves not only "to honour the Lord" (Ex 35:2), but also to distinguish God's chosen people from other peoples. Therefore, every Israelite who works on Shabbat should receive the death penalty: For, according to biblical understanding, he thereby endangers the uniqueness and destiny of this people, on which its survival depends. Num 15:32 EU illustrates this narratively: there God orders Moses to stone a man who had gathered wood on Shabbat; the Israelites obey this. These death penalty commands for Shabbat breaking are usually dated to the time of the Babylonian Exile (586-539 BC): At that time, exiled Jews had no autonomous right, so they could hardly have carried out a death penalty. These Torah passages were probably more intended to taboo the identity-threatening non-observance in non-Jewish surroundings.

Prophecy

The first scriptural prophets of the 8th century BC already presupposed a weekly day of rest, celebration and worship as known in the Northern Kingdom of Israel and Southern Kingdom of Judah. According to Am 8:5 EU, no commercial activities were to take place on it, so that it should limit profit-making and exploitation. Hos 2:13 EU included it in the announced judgement on all Jewish festivals; Isa 1:13 EU criticised its abuse as mere ritual.

Jeremiah exhorted the Israelites in the 6th century BC to observe the Shabbat, as well as the Decalogue as a whole, as an indissoluble part of YHWH's special covenant with their forefathers, and to cease commercial activities in the process: This was the condition for the survival of Jerusalem and Judah (Jer 17:9ff. EU). Otherwise their downfall was imminent (Jer 7:8ff. EU).

The exiled prophet Ezekiel mentioned the Shabbat particularly often. This day belonged to God and was his covenant sign. Its desecration was one of the grave breaches of the Torah and a subsequent sign of the fundamental breach of the covenant of God's people, which had caused their exile. This is interpreted as a distinction from attempts by earlier kings of Judah since Manasseh to weaken the Shabbat commandment in order to assimilate cultically and politically with the Assyrians and Babylonians.

After the exile, Trito-Isaiah emphasised that the Shabbat belonged to God. Its observance by Jews fulfilled the Israel covenant, but non-Jews could also obtain God's blessing through it (Is 56:1-8 EU). The Shabbat was not a heavy duty, but given for all-round joy and the enjoyment of freedom from everyday activities; its observers would receive Jacob's inheritance (Israel's salvation privileges, Gen 12:1-3) (Is 58:13f. EU). Finally, in the new creation, all mortal life would serve God "from Shabbat to Shabbat" (Isa 66:23 EU).

Other

After the return from exile and the rebuilding of the Jerusalem Temple, Nehemiah reminded the Jews of the Shabbat commandment (Neh 9:14 EU) and enacted special measures to prevent production, transportation and trade on the Shabbat (10:32 EU; 13:15-22 EU). The Shabbat established as a distinguishing feature in the exile thus apparently had to be made binding anew.

In no wisdom writing among the Ketubim is Shabbat mentioned; in the Psalms it occurs only in a secondary heading to Ps 92 EU.

God Resting on Shabbat, Russian Bible Illustration 1696

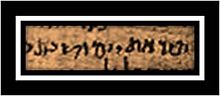

4th commandment: זכור את יום השבת zachúr et jom ha-schabbat - Remember the Shabbat day. Papyrus Nash, 2nd century BC.

Extrabiblical Shabbat rules

The Shabbat commandment, which was cultically unconditional and undefined with regard to the prohibition of work, was elaborated in detail in post-exilic writings. These extra-biblical Shabbat regulations have been intensively discussed and developed for thousands of years. Thus, they still form an essential part of the inner-Jewish culture of dispute.

Jubilee book

The Book of Jubilees (c. 150 BC) presupposes the regular weekly Shabbat throughout the year as part of the Jewish calendar. Jub 2:17-33 describes it as a particularly holy holiday, but to be observed only by Israelites, not gentiles. The death penalty for breaking Shabbat was to be retained at all costs; however, it remains open who was to carry it out and how. A list of detailed Shabbat rules in Jub 50:6-13 resembles the rules of the Damascus Scriptures and anticipates later Shabbat rules (halachot) of the Sadducees and the Mishnah. Forbidden are land and sea travel, ploughing one's own or another's fields, lighting fires, riding horses, slaughtering and killing any living creature, fasting, waging war. For all these offences, God's killing vengeance is requested, so that the previously demanded death penalty need not have been implemented by humans.

Dead Sea Scrolls

Among the Dead Sea Scrolls, the fragmentary Shabbat songs (4QShirShabb) describe the priesthood of angels celebrating in heaven the first thirteen Shabbats of the year. This apparently corresponded to a Shabbat liturgy of the time. The Damascus Scripture (c. 100 B.C.) demands strict observance of the Shabbat commandment (VI,18) and transmits detailed discussion results on its interpretation (X-XII). The eruv ("Shabbat boundary"), i.e. the area around a house in which essential items could be carried around, was shortened from 2000 to 1000 cubits. On Shabbat it was forbidden to prepare food, drink outside the house (CD X:21-23), carry water in vessels, fast voluntarily, pick up stones or dust at home, help with animal births, rescue animals and people who had fallen into wells (XI:13-17) and have sexual intercourse in the sanctuary. It was also rejected to interpret the way for carrying objects from house to house as a common courtyard and thus to allow it (CD X,4). The death penalty for breaking Shabbat was not demanded (XII,3f.).

Talmud

The Talmud collects the rabbinic regulations on Shabbat primarily in the mixed-natraktats Shabbat and Beza and Eruvin. They specify which types of activities and individual activities derived from them are to be regarded as work (melacha) impermissible on Shabbat. The rabbis were aware that some of their interpretations went far beyond the Shabbat commandments of the Torah (mHag 1:8): the laws of Shabbat were "like mountains hanging from a hair: They have little writing, but many precepts." Basically, all rabbinic regulations are subject to the commandment Lev 18:5 EU: The person who carries them out will live by them.

→ Main article: Pikuach Nefesh

Shabbat VII,2 prohibits 39 melachot ("fathers") of works. He derives these from the activities and products required for the construction of the "tabernacle" (Ex 35-39 EU) mentioned there, in the context of which the Shabbat commandments Ex 31:12-17 and 35:1-3 stand. They concern elementary needs such as food, clothing, housing, energy production and writing. To this end, he lists all the sub-steps of a product's manufacture, such as 11 for bread (ploughing, sowing, reaping, sheaf-tying, threshing, worming, sifting, grinding, sifting, kneading and baking); 13 for cloth, including shearing, bleaching, carding raw material, dyeing, spinning, weaving, sewing, tying knots, untying knots, tearing; nine to parchment, including setting traps, shafts, flaying skin, tanning, scraping, cutting to size, writing on, erasing; two to erecting and dismantling the tabernacle (building, destroying); lighting and extinguishing a light or fire (with reference to Ex 16:23; 35:3); hammering; and publicly carrying around private property. From these 39 main categories, he derives "offspring" of prohibitions concerning similar or related work: including long walks and journeys, as well as all gainful work, commercial transactions and work concerned with making money, including the mere touching of money.

Further sections clarify the general prohibitions by discussing individual cases and possible exceptions. Actions necessary for the protection of life were permitted under certain, precisely defined conditions; what was necessary for this was often disputed. If one's life was in danger, many rabbis permitted escape (Tanh 245a), the extinguishing of a fire (Shab XVI:1-7), some also self-defence up to and including killing the enemy (with reference to 1 Macc 2:29-41). Many rabbis allowed emergency aid for animals on Shabbat (bShab 128b), because animal protection was superior to the Shabbat commandment in the Torah. Eating, drinking and elementary personal hygiene on Shabbat were permitted, but not medical treatment, except to save lives (Mekh to Ex 31:13). Minor medical procedures were classified as permitted eating and drinking (Shab XIV,3f).

Some rabbis permitted medical treatment even if the danger to the life of the person concerned was uncertain, according to the principle (Joma VIII,6): ...any doubt of the danger to life supersedes the Shabbat. Rabbi Simeon ben Menasja and Rabbi Jonathan ben Joseph justified this principle around 180 with reference to Ex 31:13f. EU as follows (Joma 85b):

"Behold, the Shabbat is given to you, not you are given to the Shabbat."

The passivum divinum "to hand over" means God's activity. Rabba bar Chana and Rabbi Eleazar justified the principle with biblical analogies: For a possibly life-saving testimony, witnesses may even be taken away from sacrificing at the altar, i.e. interrupting the Torah-performed sacrifice. According to the Torah, circumcision is also required on Shabbat; since this only affects one limb, saving the whole body on Shabbat is all the more permissible. At the end of this discussion, Rab Yehuda, on behalf of Rab Shemuel, referred to Lev 18:5: The commandments were given for life. No regulation that interprets the Torah may have an adverse effect on life. Raba described this as an irrefutable argument.

The Shabbat limit for permitted transports was extended to the common courtyard. It was disputed whether one was allowed to begin work before Shabbat that continued by itself on Shabbat, such as dyeing. Students of Rabbi Hillel answered in the affirmative, students of Shammai in the negative (Shab I,4f). This diversity of opinion remained for centuries, without any one direction claiming and gaining uniqueness of interpretation. In cases of doubt, however, one should rather keep the Shabbat rest than break it (Tanh 38b).

Shab IV,1,1-3 deals with the question of how cooked food and hot drinks can be kept warm despite the prohibition to make fire or to boil. Permissible means of keeping warm were listed as garments, fruits, pigeon feathers, shavings, fine or coarse flax shavings, skins and wool flocks. For the transport of foodstuffs, a distinction was made between permitted and non-permitted means of keeping warm. Material that could rot or ferment if it got wet was forbidden; in the case of permitted material, its use was instructed so as not to contaminate the food.

Many of the exceptional clauses collected in the tractate of the same name were called "mixtures" (eruvim) because they mixed activities of one category with those of another in order to lift the original strict prohibition under a different aspect. Because of this discernible intention, the Sadducees and later the Karaites completely rejected such special rules.

The consensus among rabbis was that the Shabbat was created and commanded only for the Jews, thus directly expressing Jewish identity. According to one rabbi, non-Jews who observed Shabbat therefore deserved to die (around 250).

Following prophetic statements, the Talmud closely links Shabbat with the expectation of the Messiah (Midrash Exodus Rabbah 25:12):

"If Israel would truly keep Shabbat just once, the Messiah would come, for keeping Shabbat is tantamount to keeping all the commandments."

Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai taught (Shab 118b):

"If the Israelites would keep two Shabbatot as prescribed, they would be redeemed immediately."

The practical, experiential and transformative anticipation of this messianic time of salvation, in which creation reaches its goal, is expressed by the Talmud in the gift of a double soul (b Bava Mezia 16a):

"On the eve of the Shabbat the Holy One, blessed be He, gives man an extra soul, and at the end of the Shabbat He takes it from him again."

Mishnah, Vilna Edition, Order Mo'ed, Regulations for Shabbat

Historical developments

Ancient

In a letter written around 701 BC, the Assyrian king Sanherib described his conquest of Lachish on the "seventh (time)" of Hezekiah, then king of Judah. It is assumed that the Jews' day of rest was meant and that this enabled the Assyrians to win. The first Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem in 597 BC, the first attack of Nebuchadnezzar on the temple city in 588 BC and its fall in the reign of Zedekiah (Jer 52:5-8 EU) are also dated on a Shabbat by comparing biblical dates with Babylonian chronicles. According to this, the great kings of the Assyrians and Babylonians used this specifically Jewish day of rest, known to them, to more easily put down the rebellious Jews. The Ptolemies and later the Seleucids also attacked the Jews more often on a Shabbat because they did not exercise military resistance on this day out of loyalty to the Torah.

According to the books of the Maccabees, written around 170-100 BC, Jews were massacred by the army of Antiochos IV because of the strict observance of Shabbat rest (1 Macc 2:29-38). As a result, the Maccabee Mattatias and his followers would have decided to fight on the Shabbat in case they were attacked, in order not to be completely destroyed (1 Macc 2:39ff.; 2 Macc 5:25f.). With this exceptional rule (takhana), the ordinance (halacha) that had existed since the Jubilee Book was not abrogated, but modified for acute needs.

The decision remained controversial and was not always observed. According to the Roman historian Cassius Dio, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus was able to conquer Jerusalem on a Shabbat in 63 BC; Sosius, on the other hand, had only been able to place Jerusalem back under the Roman procuracy after the end of Pontius Pilate's term of office in 37 AD against strong Jewish resistance, even on the Shabbat. Around 100 AD, the pro-Roman Jewish historian FlaviusJosephus described the dilemma of believing Jews as Agrippa's speech during the siege of Jerusalem in 66: He who kept the Shabbat commandment in war would, like the forefathers, be easily defeated. Whoever broke it would no longer be defending Judaism and its identity, and could just as well leave war alone. For how could one still call upon God for help whose commandments one disregarded? Later, rebellious Jews would have attacked the Romans on a Shabbat, who had not expected it because of the Jewish day of rest. According to letters of Bar Kochba around 135, rebellious Jews also at least observed the prohibition of travel and trade on Shabbat.

In the Jewish diaspora, the Shabbat was observed as a day of rest for work and trade and for worship since about 500 BC, just as it was in Palestine, so that it was generally known as a special feature of Judaism and was increasingly respected by non-Jews as well. The authorities of the Roman Empire protected Jewish minorities from attacks by Greek cities on their Shabbat customs, exempted Jews from military service, from court appointments on Shabbat and preparation days for Shabbat, and kept grain distributed on Shabbat for Jewish beneficiaries to hand over to them the following day. After the suppressed Jewish uprising of 135, however, Emperor Hadrian banned large parts of Jewish religious practice, including the Shabbat.

Egyptians, Greeks and Romans influenced by Hellenism, including Apion and Manetho, saw the Shabbat as a curiosity and a sign of weakness, superstition and laziness on the part of the Jews. The prohibition of warfare on Shabbat was considered foolishness and absurdity by Agatarchides of Knidos, for example. Tacitus considered Jewish customs "sinister and shameful". He believed that Jews did not work every seventh year because of an inclination to idleness and that they worshipped the astral god Saturnus on Shabbat, whom he understood as a symbol of negative striving for power (Annales 5,4,3-4). Seneca was outraged by the influence of Jewish Sabbath observance on gentiles: "The vanquished have given laws to the victors." He described Jewish Shabbat observance as the loss of a seventh of one's life time, which would have been better devoted to urgent business. Aulus Persius Flaccus sneered that the Jews would celebrate Shabbat behind smudged windows with smoking lamps. According to Plutarch, Jerusalem's conquest happened on a Shabbat (70) because of the "low habits" of the Jews, who were "entangled in their superstitions as in a net". Rutilius Claudius Namatianus summarised this widespread contempt in a poem around 400:

"Dishonouring abuse has come from us to the wicked sex...,

That celebrates its sad Sabbaths in league with folly. [...]

To dishonouring rest it

condemns the seventh day,

As it were a female image of the weary god.

Oh that Rome had never subdued Judea,

Since the conquered people defeat their conquerors."

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

In the Middle Ages, Jews continued to develop the Shabbat customs (מנהגים minhagim) on the basis of the Torah and Talmud provisions that had been handed down. In the 13th century, three Shabbat middles were created, and later a fourth. The Zohar (c. 1280) justified them on the grounds that Shabbat was a name of God and thus signified perfect universal joy: it nurtured all Jews as offspring of the three original fathers and protected all living beings in the cosmos from God's judgement. In the 16th century, representatives of the Kabbalah in Safed created a fixed Shabbat liturgy for the house celebration with the Kiddush at the beginning and the Hawdala at the end. While the Karaites also forbade lit lights before the beginning of Shabbat, they permitted the lighting of two lights as a symbol of the soul doubled on Shabbat, enabling the perception of creation and its future salvation. Isaac Luria (1534-1572) supplemented the ritual greeting and catching up with the "bride" (Kabbalat Shabbat) with psalm singing and semiroth. Schlomo Alkabez (1505-1584) composed and wrote the Hebrew Shabbat song לכה דודי Lecha Dodi, which is still customary in all Jewish traditions today: "Let us go, my friend, to meet the bride, Queen Shabbat we will receive". The now customary reading of Prov 31:10-31 EU at the first Shabbat meal was understood by Isaiah Horovitz in 1623 as an invitation for the Hebrew שְׁכִינָה Shechina (indwelling of God). In the Central European summer, the beginning and end of Shabbat were timed differently locally, independently of sunset. Jewish philosophers declared the Shabbat to be a proof of God and supplemented its character of rest with the obligatory study of the Torah.

In 1158, Abraham ibn Ezra rejected attempts to celebrate Shabbat from Saturday to Sunday morning. In 1546, Solomon Adret forbade stove heating on Shabbat in winter and recommended a lock on the stove for this purpose. Since tobacco smoking fell under the fire prohibition, Jews lit a large water pipe on Fridays, whose tobacco continued to smoulder on Saturdays. According to Mendel ben Abraham, in 1675 Jews in Amsterdam were no longer to buy fish from non-Jews for two months, as the latter had exploited fish purchases from Jews, especially herring and carp, for Shabbat by charging high prices. Jewish merchants sold their shops to non-Jews on Fridays for a symbolic price and bought them back after Shabbat ended; if they had Christian business partners, they left the Shabbat earnings to them.

As an overview of the more developed halakhot, Maimonides wrote his major work, Guide of the Undecided, between 1176 and 1200. According to this, the Shabbat commandment was intended to affirm the createdness of the world and the existence of God, to remind us of His graces for Israel, and thus to promote theoretical knowledge of truth and practical welfare at the same time. According to the Sefer Ha-Turim of Jacob ben Asher, Shabbat was meant to commemorate the creation and Sinai revelation and to look ahead to the rest of the resurrection to come. Commenting on this for the Sephardim, Joseph Karo wrote the Shulchan Aruch ('The Set Table') from about 1545 to 1565. In a similar commentary for the Ashkenazim, HaMappa ('The Tablecloth'), Moses Isserles contrasted Sephardic and Ashkenazic Shabbat halachot. Both works became binding for Jewish life.

Modern times

Advances towards Shabbat rescheduling

For centuries, the state-imposed Sunday rest forced observant Jews living in Christianised countries to close their shops on two days of the week and made it difficult for them to rest from work on Shabbat. This put them at an economic disadvantage and discriminated against them religiously. The legal equality of the Jews demanded by the Enlightenment philosopher Christian Wilhelm Dohm in 1781 was accompanied by increased pressure for their complete assimilation. Christian citizens demanded that Jews give up their Shabbat customs in return for offered civil rights. The theologian Johann David Michaelis, for example, believed that Jews had no chance in the Prussian military because of their alleged short stature and their refusal to fight on Shabbat.

The Jewish Haskalah in the 18th century and the Jewish Emancipation in the 19th century reacted to such widespread reservations. Moses Mendelssohn, for example, replied to Dohm in 1783 that if "civil unification" could only be achieved at the price of giving up the Torah, Jews would have to do without it. For their part, however, many Jews sought to assimilate fully into the Christian-dominated nation-state in which they lived, and regarded Shabbat as an obstacle to this.

This was the subject of the German Rabbinical Conference of 1845, where Samuel Holdheim demanded that Shabbat be moved to Sunday, as this was the only way to preserve Judaism in the long term and actively sanctify the day of rest. Only individual German groups, such as the Berlin Reform congregation in 1849 and some US-American groups, followed this proposal. In 1869, Hermann Cohen again called for the Shabbat service to be moved to Sunday in order to promote the desired "national fusion". In 1919, however, he wrote that through Shabbat alone, Judaism had already proven itself to the world as a "bringer of joy and a peacemaker". Others were indifferent to their Jewish tradition or converted to Christianity for better chances of advancement.

Shabbat observance

Orthodox, Conservative, Liberal and non-believing Jews have defended Shabbat. The Christian poet Heinrich Heine honoured it in 1851 with his poem Princess Sabbath. He said it restored the dignity of the people of Israel, who had been degraded to dogs by their environment, once a week. The Zionist Max Joseph criticised Jewish emancipation as "discount Judaism", which alienated Jewish children from elementary traditions such as Shabbat and thus led to the self-dissolution of the Jewish religion. Samson Raphael Hirsch warned: "Eradicate Shabbat and you have broken the ground of Israel and its religion. Shabbat observance determines one's affiliation to Judaism. Achad Ha'am, the founder of Cultural Zionism, emphasised in 1895: "A Jew who feels a real connection to the life of his people will find it utterly impossible to imagine Israel's existence without the Shabbat. It can be said without exaggeration: more than Israel has preserved the Shabbat, it has preserved Israel."

Because the Shabbat commandment was supposed to be the exclusive covenant sign of the chosen people according to the Torah, devout Jews often rejected its Christian use for Sunday. From around 1900, Jews who were faithful to the Shabbat organised themselves into associations called שומר שבת Shomre Shabbat ('guardians of the Shabbat'). They sought to fulfil not only the Torah but also the halachot completely, and published books and pamphlets with practical advice to this end. They formed a 'World Association for Shabbat Protection Shomre Shabbos' in Berlin in 1928. Such associations and their predecessors achieved partial exemption from the legal Sunday rest for Jewish businesses in England (1860 and 1931), the Netherlands, Galicia and Bukovina, for example. In Prussia, Jewish schoolchildren had been exempt from classes on Saturdays since 1859. The special regulation existed until 22 June 1933.

Other believing and non-believing Jews, like Philo of Alexandria, emphasised the relevance of the Shabbat for humanity. Leo Baeck wrote in 1906 that the Sabbath commandment Dtn 5 was meant to protect the unabridged and unabridged human right of slaves and female slaves. The commanded rest for all members of the family should also grant the servants dependent on them the rest necessary for their survival. According to the Torah, they too have a right, granted with all God's authority, to rejoice in Shabbat in the same way as the free, and are therefore already religiously equal to them. He pointed out that the Romans also knew about slave festivals, but limited them to a few days a year and did not regard them as a slave right, but as alms.

Anti-Semites often used the Sabbath to attack Jews: during the First World War, for example, they had to open their shops on Saturdays from 1916 onwards. The National Socialists' boycott of Jews on 1 April 1933, a Saturday, was again to affect assimilated Jews. Jewish children had to go to school on Saturdays again from 26 June 1933. Inciting pamphlets derided Jewish Sabbath observance as laziness and alleged exploitation of non-Jews. With decrees, Jews were also forced to work on Friday evenings, Saturdays and their feast days. The obligation to work was constantly tightened and non-compliance was punished ever more severely, especially in Poland, which had been occupied since 1939.

As a result, Polish rabbis often allowed their congregations to work and cook hot soup on Shabbat and High Holy Days when their lives were in danger. Strictly religious Jews in the ghettos, however, often had themselves divided into brigades that did not work on Shabbat, but had to do particularly unpleasant work and received fewer food rations. Jews interned in temporary camps refused to accept temporary releases deliberately offered always on Saturdays because of the halachic travel ban. Deported Jews celebrated Shabbat with candles and the singing of the Lecha Dodi even on the way to their murder on railway platforms, in railway carriages and in extermination camps; so did survivors after their liberation.

In several of his writings, the psychoanalyst and social philosopher Erich Fromm dealt with the Sabbath, which he considered the most important idea in the Bible. In 1980 he explained its meaning as follows: "The Sabbath is the anticipation of the messianic time not through a magical ritual but through practical behaviour that puts man in a real situation of harmony and peace. The other practice of life changes man." "In Jewish tradition, the highest value is not work, but rest, the state that has no other purpose than to be human. But the Sabbath ritual has another aspect that one must know in order to understand it fully. The Sabbath seems to have been an ancient Babylonian holiday, celebrated on every seventh day (Sabattu) of a lunar month. However, it had a completely different meaning from the biblical Sabbath. The Babylonian Sabattu was a day of mourning and self-chastisement. It was a gloomy day consecrated to the planet Saturn (the English name for Saturday still indicates this today) and people sought to appease their anger through self-mortification and self-punishment. In the Bible, however, the holy day has lost its character as a day of self-flagellation and mourning; it is no longer a "bad" day, but a good day; the Sabbath has become the opposite of the gloomy Sabattu." Fromm's association of the Sabbath with the ideal of an egalitarian society expected as the goal of history followed authors of early socialism and communism such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Moses Hess, who called the perpetual Sabbath the "Sabbath of history", and Karl Marx.

Under certain circumstances, turning on devices while observing Sabbath rest is made possible by the grama technology developed in Jerusalem in the 2000s. Certain devices have the so-called Sabbath mode for the same purpose.

Design differences

The basic components of the Shabbat, which have existed for thousands of years (rest from work, ritually opened feasts in the family and synagogue services) are intended to express the joy in God's work of creation and in the conclusion of the covenant. Since the Middle Ages, Jews have interpreted the Torah's non-specific prohibition of work in different ways, depending on their religious beliefs.

Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews (יַהֲדוּת חֲרֵדִית jahadut charedit, Haredim) still observe the 39 melachot, the 39 prohibitions on work in the Talmud, so in larger Haredi residential neighbourhoods such as the former Eastern European shtetls, the Scheunenviertel (Berlin) and Jerusalem's Old City. Their representatives continue to discuss the halakhot in responsa and try to adapt them to modern conditions and technology. Since the use of electricity has been included in the fire ban since 1900, this has resulted in the prohibition of using lifts, escalators, cars, listening to the radio, watching television, etc. The use of electrical devices with batteries charged before Shabbat, devices necessary for medical operations, etc. was controversial. In order to solve such problems practically, Levi Jizhak Halperin founded the "Institute for Science and Halacha" in Jerusalem in 1963. There, for example, a "Shabbat socket" was invented that interrupts the electric circuit for 30 seconds every three minutes to allow appliances to be plugged in without breaking the fire ban. Some modern refrigerators and ovens have a Sabbath mode that allows them to be used on the holiday without human switching.

In liberal and progressive Judaism, the Shabbat purpose of joyful and peaceful rest and spiritual renewal in the circle of family, friends and guests is emphasised. The prohibition of work is recognised in principle, but not formally defined according to biblical and Talmudic passages, but according to contemporary social conditions. Ordinary gainful employment and trade are refrained from as far as possible; those who absolutely have to work on Shabbat should use the time off work all the more for spiritual reflection. The use of electricity is not generally forbidden. If activities serve the sanctification of Shabbat, they are permitted, such as driving a car to attend synagogue, restful gardening, writing as part of a creative service. The responsibility of the individual is emphasised: negligence is permitted, but whoever transgresses a commandment also deprives himself of the pleasure associated with its observance. In 1972, the Central Conference of Rabbis in the USA published a Shabbat Manual in order to relate the halakhic rules to modern living conditions and needs.

Between 1924 and 1934, the Zionist poet Chaim Nachman Bialik first introduced regular, informal, non-halacha-oriented public Friday evening meetings with his friends in Tel Aviv, which quickly became popular, especially among young people. He called them Oneg Shabbat (Shabbat delight, joy, enjoyment), following Is 58:13 EU, in order to emphasise this aspect, which is essential for the whole Shabbat. From 1939 to 1944, Oneg Shabbat was also the cover name of a Jewish resistance group in the Warsaw Ghetto and the associated archive of Emanuel Ringelblum.

Shabbat in Israel

In Israel, the long-established Jews had kept Shabbat strictly according to the Halacha, while the immigrants (עולים olim) of the first and second עֲלִיָּה aliyah celebrated it without special services and also varied the starting dates. The British Mandate administration granted the settlers communal autonomy, so that a variety of Shabbat arrangements emerged.

On 14 May 1948, Shabbat was established as a legal day of rest, as the Jewish Agency had promised Orthodox Jews on 19 June 1947. At the same time, non-Jews were guaranteed the right to observe their own days of rest and holidays. In 1951, the Knesset passed a law guaranteeing a weekly rest period of at least 36 hours for all Israelis and prohibiting employment during it, but allowing exceptions for national defence, public security and government services, for example. These may only be approved by a committee consisting of the prime minister, the minister of labour, the minister of religion and the minister of defence. Since the halacha regulations have not been regulated by law, conflicts often arise over questions of detail.

In Israel, most shops are closed on Shabbat and public transport is at a standstill, except in Haifa. In multi-storey hotels, a Shabbat lift works. It goes up and down automatically and stops at every floor, so there is no need to press a button. In the strictly religious Jerusalem neighbourhood of Me'a She'arim, all restaurants remain closed on Shabbat, in other neighbourhoods most are, as well as in Tel Aviv, Haifa and other places where Haredim do not make up a majority of the population. A ban on El Al airline flights on Shabbat has often put it in financial straits. Israelis, meanwhile, are allowed to take part in space flights with rabbinical permission if they keep Shabbat in space after Jerusalem local time. In Petach Tikva, Orthodox Jews attacked restaurants and cinemas open on Shabbat in 1984; after the arrest of the grand rabbi involved, the Agudat Yisra'el party threatened to break the governing coalition. In 1986, Prime Minister Shimon Peres banned the Ramat Gan City Council from using the local stadium for football matches on Shabbat. A popular kibbutz Shabbat flea market met with fierce protests in 1986, as did a cable car built in Haifa to run on Shabbat. In 1987, thousands of Haredim demonstrated in Jerusalem in front of open cinemas and restaurants to force their closure on Shabbat.

The deserted Ben Yehuda Street in Jerusalem on Shabbat

Hawdala. Illustration 14th century, Spain

.jpg)

Saturday, scene in front of the synagogue in Fürth, the women (left) wear Empire-style dresses, the men the festive costume of the traditionally living Jews in South and West Germany, Germany c. 1800

Section of an eruv (Shabbat boundary or fence) in Jerusalem.

Barches/Challot

Shabbat celebration

Despite centuries of tradition that have led to the same elements in liturgy and customs worldwide, Shabbat is celebrated differently not only according to religious direction, but also according to local custom. Individual elements are omitted or modified, others are added. Yom Kippur is the only fast day that is also celebrated on a Shabbat - the other fast days are postponed if they fall on a Shabbat.

Preparations

According to Talmudic rules, Shabbat should be prepared by all participants together on Friday before dusk. The evening beginning is designated by the word Erev (Hebrew ערב evening) The evening before is therefore called ערב שבת "Erev Shabbat". This includes tidying up and cleaning the home, a cleansing bath, cutting hair and nails, and dressing in festive clothes worn only on Shabbat. Three meals are cooked for the evening instead of the usual two. It is a good custom to invite guests to the first Shabbat meal, especially strangers and people passing through. The table is set festively: two Shabbat breads covered with a cloth (Hebrew חַלָּוֹת Challot) lie in front of the head of the family, recalling the double manna during the Israelites' wanderings in the desert, and the cup for the Kiddush. The weekly Torah portion (the mikra) is read three times, twice in Hebrew, once as an Aramaic targum or according to the Rashi commentary. Items that may not be moved or used on Shabbat are מוקצה Muktza. For Shabbat day (on Saturday), Jewish cuisine has developed many cold dishes that simmer slowly for a very long time over a very low flame, which can be pre-cooked on Friday, including cholent (Eastern Yiddish, a kind of stew).

Friday evening

Dusk marks the beginning of Shabbat Eve (ליל שבת Leil Shabbat). Twilight is considered to have fallen "when one can no longer distinguish a blue woolen thread from a grey woolen thread". Before nightfall, the woman of the house traditionally lights the Shabbat candles and says the blessing.

| Blessing for the lighting of the lights | ||

| Hebrew | Transliteration | Translation |

| בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה אֲדֹנָ-י אֱ-לֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ לְהַדְלִיק נֵר שֶׁל שַׁבָּת קֹדֶשׁ | Baruch ata Ado-naj, Elohenu Melech Ha'Olam, ascher kideschanu bemizwotaw, weziwanu lehadlik ner schel Shabbat kodesh. | "Praise be to You, Eternal, our God, King of the world, who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to kindle the Shabbat light." |

The synagogue service on Friday evening, which in Orthodox congregations is usually not attended by women, begins with the "reception of Shabbat" (קבלת שבת Kabbalat Shabbat) through a sung Psalm (selection: Ps 29 EU; 92-93; 95-99) and the traditional Shabbat song לכה דודי Lecha Dodi. The evening prayer that follows (מעריב Maariw) is shortened on Shabbat by some parts, which contain concern and confession of guilt, for example, and extended by Shabbat texts. The Kiddush has also been transferred from the house celebration to the service liturgy.

| Sanctification of Shabbat - Genesis 1: 31b-2: 3 | ||

| Hebrew | Transliteration | Translation |

| ויהי ערב ויהי בקר יום הששי. | Va-y'hi erev va-y'hi voker, yom ha-schischi. | And it was evening and it was morning, the sixth day. |

| ויכלו השמים והארץ וכל צבאם. | Va-y'chulu ha-schamayim v'ha-aretz v'chol-tzva'am. | And the heavens and the earth were finished together with all their host. |

| ויכל אלהים ביום השביעי מלאכתו אשר עשה | Va-y'chal Elohim ba-yom ha-shvi'i m'lachto ascher asah, | And on the seventh day God finished his work that he had done. |

| ויברך אלהים את יום השבעי ויקדש אתו | va-y'varech Elohim et yom ha-shvi'i, va-y'kadesh oto, | And God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it. |

| כי בו שבת מכל מלאכתו אשר ברא אלהים לעשות. | ki vo shavat mi-kol-m'lachto, ascher bara Elohim la'asot. | for on it he rested from all his work for which God had created. |

This introduces the following domestic Shabbat celebration. Traditionally, the father of the family welcomes the Shabbat with the greeting of peace (Hebrew שלום shalom), blesses the children if necessary and speaks the verses Gen 2:1-3, which were already part of the evening Shabbat amida. Then he says the blessing over a full cup of wine, today usually sweet red wine:

| Blessing over the wine | ||

| Hebrew | Transliteration | Translation |

| בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הַגָּפֶן: | Baruch atta adonai, elohenu melech ha-olam, bore pri ha-gafen. | "Blessed are you, Eternal, our G'd; you rule the world. You have created the fruit of the vine". |

All present answer: אָמֵן Amen

| Continuation of the Kiddush | ||

| Hebrew | Transliteration | Translation |

| ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם | Baruch Atah ADONAI, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, | Blessed are you, O LORD our God. |

| אשר קדשנו במצותיו ורצה בנו | asher kid'schanu b'mitzvotav, v'ratzah vanu, | who sanctified us with his commandments and was pleased with us, |

| ושבת קדשו באהבה וברצון בנחילנו | v'Shabbat kadscho b'ahavah u-v'ratzon hinchilanu, | and has given us his holy Shabbat as an inheritance with love and favour, |

| זכרון למעשה בראשית. | zikaron l'ma'aseh v'reischit. | as a reminder of the work of creation in the beginning. |

| כי הוא יום תחלה לצקראי קדש | Ki hu jom t'chilah l'mikraei kodesh, | For this day is the most important of our holy times, |

| זכר ליציאת מצרים. | zecher l'tziat Mitzrayim. | a reminder of the Exodus from Egypt. |

| כי בנו בחרת ואותנו קדשת מכל העמים. | Ki vanu vacharta v'otanu kidaschta mi-kol-ha-amim. | For you have chosen us from all nations and sanctified us. |

| ושבת קדשך באהבה וברצון הנחלתנו. | V'Shabbat kaj'cha, b'ahavah u-vratzon hinchaltanu. | You have given us your holy Shabbat in love and joy as our inheritance. |

| ברוך אתה יי מקגש השבת | Baruch Atah, ADONAI, m'kadeish ha-Shabbat. | Blessed are you, O LORD, who sanctifies Shabbat. |

This is followed by a Shabbat blessing, which recalls the beginning of creation and the exodus from Egypt.

After the father and the table company have drunk from the wine, the hands are washed before the meal, as always; according to some local traditions already before the Kiddush. Then he says the usual blessing over the bread:

| Blessing over the bread | ||

| Hebrew | Transliteration | Translation |

| ‑בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ‑יְיָ ‑אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם הַמּוֹצִיא לֶחֶם מִן הָאָרֶץ: | Baruch ata Ado-naj, Elohenu Melech Ha'Olam, Hamozi lechem min haarez. | "Praise be to You, Eternal One, our G'd, who causes bread to come forth from the earth". |

He sprinkles a piece of it with salt and eats it. Then he cuts or breaks off pieces of the bread and distributes them or passes the bread with the salt so that everyone can take a piece. Shabbat songs (זמירות Semirot) are often sung during the meal, including Psalm 126. After the meal, the table prayer (ברכת המזון Birkat Hamason) is sung together more solemnly than on weekdays.

The social gathering for festive eating, singing, chatting and reflection on Friday evening - in some places also on Friday or Saturday afternoon - is called oneg shabbat, regardless of its design, following Is 58:13 EU. It can also take place outside the domestic-family setting, for example in public restaurants. Kiddush and blessings are then performed more variably, for example at several tables or not at all. Instead of the traditional interpretation of the Torah by the father of the family, there can be spontaneous religious recitations by anyone present.

Saturday morning

The main Shabbat service on Saturday morning is attended by men and women. Its centrepiece is the Torah reading after the morning prayer. In a festive procession, the Torah scroll is carried in song from the Torah shrine through the synagogue and finally unrolled on the reading desk, rolled up again after the reading and carried back. Before and after the reading, the person called up says a special bracha, Birkat ha-Tora.

In many congregations, following the reading, the person called receives a Mi scheBerach ('He who blessed'), a special blessing in which family members or the sick may be remembered in addition to their name. In many congregations it is also customary to commemorate charitable institutions. After the reading from the Torah is completed, the Haftara, the reading of a passage from the Nevi'im (Books of the Prophets), follows. In many congregations, the Torah reading is followed by a general Mi scheBerach said for the sick or otherwise in need. This is followed by prayer for the congregation, for the country and its government, and in many congregations for the State of Israel.

In contrast to the weekday service, an additional prayer, the Musaf prayer, as a substitute for the sacrifice in the time of the Temple, and further psalms and hymns were included in the Shabbat and holiday service. The Musaf prayer is either not prayed or redesigned accordingly by Reform congregations and many Conservative congregations who view the Temple and its sacrificial service as a historical, outdated manifestation of Jewish worship. On Shabbat, the eighteen-prayer prayer (Amida) is reduced to seven individual petitions, since one should not worry on Shabbat but trust in God's care. No tefillin are laid on Shabbat either.

Saturday noon till evening

The subsequent communal meal is again opened with the Kiddush. The blessing over the wine is traditionally preceded by Ex 31:16 EU: "And the children of Israel shall keep the Shabbat...". Freely chosen words of interpretation on the current parashah during the meal are also customary, as is the singing of semirot. The intervening times are for rest, self-reflection, walking and learning Torah.

The mincha prayer in the afternoon is followed by the "third meal" (se'uda schlischit) of Shabbat. Words from the Torah, singing for spiritual edification and a reflection during dusk characterise it. According to ancient tradition, the final redemption of the Jewish people takes place on a Shabbat afternoon. Dreams and mourning, longing and hope are mixed into the melodies of this hour. After the communal table prayer, in which the person leading the prayer says the blessing over a "glass of blessing", the full glass remains until the evening.

Torah scroll and Torah pointer (Jad)

Sabbath Court Cholent

Friday evening, painting by Isidor Kaufmann (1853-1921)

Hawdala candle with kiddush cup and besamim box

Shabbat exit

At the "Shabbat exit" (Hebrew מוצאי שבת Motza'e Shabbat) in the context of the havdala, a blessing is again said over the glass of wine after the weekday evening prayer. When lighting the multi-wicked havdala candle, the following blessing is said:

| Hebrew | Transliteration | Translation |

| הנה אל ישועתי אבטח ולא אפחד | Hineh El yeshuati, evtach v'lo efchad. | Behold, God is my salvation, I will trust and not be afraid, |

| כי עזי וזמרת יה יי ויהי לי לישועה. | Ki ozi v'zimrat Yah ADONAI va-y'hi-li lischuah. | For the Lord my God is my strength and my song. He has also become my salvation. |

| ושאבתם מים בששון ממעיני הישועה. | U-shavtem mayim b'sason mi-ma'ainei ha-jeshuah. | And with joy you shall draw water from the wells of salvation. |

| ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם בורא פרי הגפן. | Baruch Atah ADONAI, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, borei p'ri hagafen. | Blessed are you, O LORD our God, King of the Universe, who creates the fruit of the vine. |

| ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם בורא מיני בשמים. | Baruch Atah ADONAI, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, borei minei v'samim. | Blessed are you, O LORD our God, King of the Universe, who creates all kinds of spices. |

| ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם בורא מאורי האש. | Baruch Atah ADONAI, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, borei m'orei ha-eisch. | Blessed are you, O LORD our God, King of the Universe, who creates the lights of fire. |

| ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם המבדיל בין קדש לחול. | Baruch Atah ADONAI, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, ha-mavdil bein kodesch l'chol. | Blessed are you, O LORD our God, King of the Universe, who distinguishes between holy and worldly. |

| שבוע טוב | Shavua tov | have a good week! |

Alternatively, the prayer אַתָּה חוֹנַנְתָּנוּ יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ לְמַדַּע תּוֹרָתֶךָ. וַתְּלַמְּדֵנוּ לַעֲשׂוֹת חֻקֵּי רְצוֹנֶךָ Ata Honantanu (for men) or ברוך המבדיל בין קודש לחול Baruch Hamavdil Bein Kodesh LeHol (for women: Blessed is he who distinguishes between that which is holy and that which is profane. ) should be prayed.

The flame of the multi-wicked havdala candle, which like a torch announces the end of Shabbat and shines into the new week, is extinguished by the remaining wine in the glass. This also includes a vessel with spices, the besamim box, whose fragrances are supposed to remind us of Shabbat in the week that is now beginning. Afterwards, one wishes each other a "good week" (Shavua tow).

Particularly religious Jews eat another meal afterwards, called "Accompanying the Queen" (Melawe Malka). Such meals are also organised as social gatherings among friends or as fundraisers for charity.

Special Shabbatot

The Shabbatot in the cycle of the year are generally named after their sidra (סדרא, also parashah פרשה), the weekly section that is read from the Torah. (See list of weekly sections). Some, however, have their own function and meaning, which their name indicates:

| Special Shabbatot | |||

| Designation | hebrew | Translation | Meaning |

| Shabbat Shuva | שבת שובה | Shabbat "Turn Back!" or "Shabbat of Repentance" | between Rosh ha-Shanah (New Year) and Yom Kippur (Feast of Atonement) according to the Haftara read on that day: Hosea 14:2-10 EU, Micah 7:18-20 EU, Joel 2:25-27 EU. |

| Shabbat Shabbaton | שבת שבתון | "the Shabbat of Shabbats", "the highest Shabbat". | Term for Yom Kippur, the seventh of the High Holidays; sometimes also for the 49th day of counting the Omer. |

| Shabbat Bereshit | שבת בְּרֵאשִׁית | "the Shabbat of the beginning" | the first Shabbat after Simchat Torah, after the first section beginning with Bereshit. |

| Shabbat Hanukkah | שבת חֲנֻכָּה | Hanukkah Shabbat | is a Shabbat during the 8-day Hanukkah festival. |

| Shabbat Shira | שבת שירה | Shabbat of Song | Beschalach, 4th section of Ex. after Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32 EU). |

| Shabbat Shekalim | שבת שקלים | Shekel Shabbat | Shabbat before or on the 1st of Adar, after the additional parashah reading dealing with the shekel levy: Exodus 30:11-16 EU. |

| Shabbat Sachor | שבת זכור | Shabbat "Remember!" or "Shabbat of Remembrance". | the Shabbat preceding the festival of Purim. The commemoration refers to what Amalek did to the Jewish people according to the Torah. Additional parashah reading: Deuteronomy 25:17-19 EU. Haftara: ashk.: 1 Samuel 15:2-34 EU, sef.: 1 Samuel 15:1-34 EU. |

| Shabbat Para | שבת פרה | Shabbat of the Red Cow פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה | the Shabbat after the feast of Purim according to the additional reading about the atonement by means of the red heifer. Additional parashah reading: Numbers 19:1-22 EU. |

| Shabbat ha-Chodesh | שבת החודש | "Shabbat of the Month | the Shabbat before or on the 1st of Nissan to establish Nissan, the month of deliverance, as the first of the months (in the Jewish year the first month is not the month from New Year's Day). Additional parashah reading: Exodus 12:1-20 EU. |

| Shabbat ha-Gadol | שבת הגדול | "the great Shabbat" | the Shabbat before Passover in the month of Nissan, its Haftara: Malachi 3:4-24 EU. |

| Shabbat Chason | שבת חזון | Mourning Shabbat | the Shabbat before the 9th Av (Tisha beAv), on which Isaiah 1:1-27 EU is read aloud as a haftara (beginning with chason, "revelation"). |

| Shabbat Nachamu | שבת נַחֲמוּ | Shabbat of Consolation | the Shabbat after the 9th Av, when Isaiah 40:1-26 EU (beginning with nachamu, "comfort!") is read aloud as a haftara. |

| Shabbat Mevorchim | שבת מברכים | Shabbat of Blessing | Blessing of the upcoming new month by the congregation |

| Shabbat Chol HaMo'ed | שבת חול המועד | Shabbat within the Middle Holidays | Middle Feasts of Passover (Exodus 12:1-20) and Sukkot. |

| Shabbat Rosh ha-Chodesh | שבת ראש החודש | Shabbat of the Month (Nissan) | the Shabbat following the new moon (Rosh Chodesh) in the month of Nissan. |

| Shabbat Chatan | שבת חתן | Shabbat of the Bridegroom | On the Shabbat before the chuppah (wedding), according to Ashkenazi custom, the groom is called to theTorah reading |

Schemitta

According to the Torah, the שמיטה Shemitta (also: Shemitta, Shemitah or שנת שמיטה Schnat Shemitta, Shemitah year, German Sabbat year) is a year of rest for the arable land and other agricultural cultivation in Israel. After six years of cultivation, the land is left fallow for one year - in analogy to Shabbat as a day of rest (Ex 23:10-11 EU; Lev 25:1-7 EU). The Shemitah year is seen as "an extension of the basic idea of the Shabbat commandment", the meaning of which is "not to extract the last - not from the resources of the earth, not from capital, not from the labour of others, and not from one's own either." In the Shabbat year, the fields were accessible to all, so even the poor could eat the finest fruit. At the end of the Shabbat year, the debts that could not be paid were cancelled, because without the opportunity to start again, many people never get an economic chance.

Data

The year after the destruction of the Second Temple was the first year of a seven-year Shabbat cycle. In the Jewish calendar, starting from Creation, this was the year 3829 (68-69 AD in the secular calendar). Counting seven years each from then on, the next Shemitah year will be the year 5782 after Creation, lasting from 7 September 2021 to 25 September 2022. The Shemitah thus has a different meaning than the Sabbatical, which is a working time model and is often also called a Sabbatical year.

Year of remission

After seven times seven years, a "year of jubilee" or year of remission (Hebrew שנת היובל schenat hajobel) should follow (v. 8-34). Every 50th year after the seventh of seven Shabbat years, that is, after every 49 years, the Israelites were to grant full debt forgiveness to their subject people, return to them their inherited land, and abolish debt bondage. These protective rights for slaves, strangers, animals, soils and plants enshrined the life-sustaining alternation of work and rest as a divine legal order to curb exploitative violent relationships. In the Talmud, the commandment of the year of remission was abolished for practical reasons: The land of Israel no longer belonged to the Jews; the biblical prohibition of interest also proved unworkable in the Roman Empire. The Torah protection rights were preserved in the form of detailed care for the poor under the generic term of צְדָקָה Zedaka (charity, literally:justice). Apart from prayer and religious study, charity is the third substitutionary act for the temple sacrifice and thus contributes to the messianic work of redemption.

The term "year of jubilee" comes from the Hebrew word jobel (יובל), which originally meant "ram". The wind instrument shofar was made from rams' horns, which was blown, among other things, to open a year of remission. Therefore, the term jobel was applied to the instrument and the year of Jubilee that it opened. The alternative term Jubilee Year became customary in Christianity from 1300 onwards for ecclesiastical calls for a year of indulgence, which was about the forgiveness of sins, and until the 16th century there was a lively trade in indulgences, especially by the popes.

Shofar

Sign in Jerusalem, Israel, indicating that the fruits there are designated as הֶפְקֵר hefker (abandoned property) on the occasion of the Schnat shmitta.

Meaning in Christianity

New Testament

The New Testament reflects the Sabbath practice in Palestinian Judaism at that time: Sabbaths were celebrated in houses with feasts, guests (Lk 14:1) and rest from work (Lk 23:56). In synagogues Torah and prophets were read, texts were interpreted (Mk 1:21; 6:2; Lk 4:16-21; 13:10; Acts 13:15, 27; 15:21; 17:2). Forbidden were harvesting (Mk 2:23), trade (Mk 16:1), carrying burdens (Mk 15:42-47; Jn 5:10; 19:42), permitted were a Sabbath walk (Acts 1:12), priestly sacrifices (Mt 12:4), circumcision of sons on the eighth day of life (Jn 7:22f.) and rescuing animals and people from danger (Mt 12:11; Lk 14:5).

Jesus of Nazareth took part in the Sabbath discussions of his time. All four canonical gospels record his actions on and statements about the Sabbath that provoked approval or disapproval. According to Mk 2:23ff. EU, Jesus' followers gathered ears of corn from fields on the Sabbath. This shows the acute famine of destitute itinerant beggars who had no landed property and could not gather sufficient food supplies the day before. When asked by some Pharisees for their permission to do so, Jesus justifies their behaviour as follows:

- David, in the distress of hunger, had received and eaten sanctified bread from the priest's altar for himself and his followers. (v.25, 26)

- The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath (v. 27).

- The Son of Man is "Lord also of the Sabbath" (v. 28).

The first two sentences argue, as is customary among Torah teachers, with biblical passages (1 Sam 21:7 EU; Gen 2:2 EU). The example of David has nothing to do with the Sabbath, but is meant to show that other, comparably high-ranking Torah commandments such as the temple sacrifice were also broken by chosen Jews when their lives were in danger. The implicit conclusion is that acute hunger is one of the exceptions that entitles one to break the Sabbath because God has made the day of rest beneficial to human life. This interpretation thus only reinforced the meaning of the Sabbath commandment, which the Torah itself explains. It corresponded to the principle of "saving life supersedes the Sabbath", which was also publicly advocated by other Torah teachers at the time of Jesus and which prevailed among rabbis according to the Mishnah (compare difference criterion).

The third sentence, however, is only found in Jesus. He claims the authority of the Son of Man, whom the apocalyptic vision Dan 7:1-14 EU expected as the representative of God's reign after the final judgement. The presupposition that God had already given him all his eternal power (LXX: exousia) justifies here his permission to break the Sabbath commandment by way of exception, as before his right to forgive sins (Mk 2,10). Both actions are thus presented as an anticipation of the universal reign of God (cf. Mt 8:20; 11:19).

According to Mk 3:1-5 EU, Jesus also healed a leper on the Sabbath, provoking other Torah teachers. Thereupon he had asked them (v.4):

"Shall one do good or evil, preserve life or kill on the Sabbath?"

Although the chronically ill man was not acutely life-threatened, Jesus counts his healing as saving life, which is also commanded on the Sabbath. In doing so, he did not transgress the Sabbath commandment, since he did no work for the healing, but merely spoke a healing word. Therefore, the aforementioned reaction of the Pharisees to plan Jesus' death together with Herod's followers (v. 6) is considered ahistorical.

Texts such as Lk 13:10-17; 14:1-6 (special Luke material); Jn 5:1ff, 7:22ff and Jn 9:16 confirm that Jesus healed on the Sabbath, thereby causing controversy and commenting on it. No sick person healed on the Sabbath is reported to be in danger of death; all could have been healed on other days. It was therefore a matter of demonstrative Sabbath breaking, so that it was not discussed whether these were violations of the rules, but only whether they were permitted in the sense of the Torah. Jesus referred to exceptions that were already permitted and concluded, for example, from the permitted saving of animals to the equally permitted healing of people (cf. Mt 12:11f.). In the Last Days, the fetters of Satan must also be loosed from the chronically ill children of Abraham (Jews) (Lk 13,16). According to Lk 13,17, this eschatological justification also met with praise from Jewish eyewitnesses of the healing and overcame the initial rejection of some. Thus Jesus did not abolish the Sabbath commandment, but relativised it for the sake of life: Helping the acutely needy took precedence. Saving lives also on the Sabbath fulfils the meaning of this commandment precisely because it is meant to protect people, especially the weak and also domestic animals, from merciless exploitation of their labour.

The early Christians recognised and kept the Sabbath commandment as a matter of course, as did the surrounding Judaism, since neither the pre-Markan account of the Passion nor the Gospels nor the Acts of the Apostles record unacceptable Sabbath-breaking by Christians and criticism of the Sabbath commandment. Paul of Tarsus was critical for the first time in Gal 4,10f. about the adoption of Jewish Sabbath halacha by Gentile Christians, which in his view endangered their overarching unity with Jewish Christians in faith in Jesus Christ. In Rom 14:5 he pleads for mutual respect of different Sabbath observances by Jewish and Gentile Christians in Rome. In Col 2:16 he stresses that no Christian should be condemned because of food or festival rules such as the Sabbath. It is questionable whether this condemnation came from a group outside or inside the predominantly Gentile Christian community addressed. Internal conflicts between Jewish and Gentile Christians are often assumed, which were not about a specific interpretation of the commandments at the time, but about the validity of the Torah for the Christian faith as a whole.

History of Christianity

The Early Church named the days of the week unchanged like the Jews and celebrated the Sabbath alongside Sunday until at least 130 (Apostolic Constitutions). Only since the final detachment from Judaism (around 135) did some Gentile Christian authors demand the replacement of the Sabbath by Sunday, such as the Epistle of Barnabas.

Constantine the Great made Sunday a legal holiday and public day of rest in 321 in order to privilege Christian worship. Sunday thus replaced the Sabbath as the weekly holiday in Christianity. This was accompanied by its theological interpretation as the "great Sabbath" (Epiphanes, Expositio fidei 24) and the equation of Resurrection Day with the "eighth day of creation". Jewish Christians nevertheless continued to celebrate the Sabbath in many cases, and some Gentile Christians also celebrated services on the Sabbath in addition to Sunday. The Council of Laodicea in 363/64 condemned this custom as Judaising. Only the Ethiopian Church kept the Sabbath on an equal footing with Sunday until modern times and even supplanted it there for a time.

Following the interpretation of God's rest in the Letter to the Hebrews (Heb 4:1-11), a spiritualising and an eschatological interpretation of the Sabbath emerged in patristics, similar to the earlier Jewish apocalyptic interpretation. Justin, Irenaeus and Tertullian interpreted the work forbidden on the Sabbath as sins, so that the Sabbath became a symbol for the Christians' turning away from the old sinful life. Augustine of Hippo therefore interpreted the Sabbath as the permanent state of Christians: In the tranquillity of a good conscience, they celebrated it constantly in their hearts. This interpretation was followed by Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure. For Origen, Irenaeus, Athanasius and Hippolytus, the Sabbath symbolised the salvation of creation completed with Christ's return. In this context, some understood the seven days of creation with reference to Ps 90:4 ("a thousand years are before thee as one day") as periods of world history (chiliasm). For Tertullian, Julius Africanus, Methodius and others, on the other hand, the completion of creation fell on the symbolic eighth day when Christ was resurrected. Therefore, for them, the Sabbath symbolised an aeon before the Parousia, a millennial intermediate kingdom in which the saints would rule the earth with Christ.

In the anti-Judaism of the High Middle Ages, Christians adopted the ancient tradition of mocking the Sabbath, for example through satirical caricatures. The Spanish Inquisition persecuted Marrans by looking for typical Sabbath characteristics: glowing candles, extinguished ovens, clean shirts, fresh tablecloths in their houses on the Sabbath were indications to arrest converted Jews, then torture them and in the end usually burn them.

The term witches' Sabbath combines the concept of witches, coined in the early 15th century, with the word Sabbath. Anti-Judaism increasingly demonised the Jews and their customs, especially in the High Middle Ages: they were accused of satanic rites in their religious practice, including the worship of demons, ritual murders, harmful spells, poisoning of wells, sacrilege of the host. This was often used to justify or bring about pogroms and persecutions against them.

During the Reformation, spiritualising and eschatological interpretations of the Sabbath were given a Christological slant. Martin Luther, in his early days influenced by mysticism, advocated the former: In the rest from one's own works, the soul becomes empty and ready for God's sole grace (WA 6,244,3ff). Following him, Andreas Karlstadt declared in a tract in 1524 that the Sabbath was commanded for the practice of serenity. Luther, however, now opposed making the Sabbath a condition for God's sanctification of man. After his catechisms appeared, this interpretation receded in Protestant theology. Karl Barth (KD III/4), Jürgen Moltmann and Christian Link renewed it in the 20th century. The eschatological interpretation of the "world Sabbath" or "Sabbatäon" was advocated by the Taborites, Thomas Müntzer and Hans Hut after Joachim von Fiore.

The English Puritans, due to their literal understanding of the Reformation sola scriptura principle and newly discovered Jewish Sabbath interpretations, demanded from the 16th century onwards strict observance of the Sabbath commandments, especially rest from work, on the Christian Sunday; some also demanded a corresponding Saturday rest. In the process, the aspect of Sabbath joy, which was decisive in Judaism, was often missing.

From the 16th century onwards, Christian communities began to observe the Sabbath as a day of rest instead of Sunday for various theological reasons. Some were Jewish Christians for whom Jesus had not abolished the Sabbath, others saw in Sabbath observance a condition that had become actual for their salvation from the final judgement that was expected to be near. Both groups are not historically dependent on each other, but are grouped together as Sabbatarians. To the apocalyptic group belong the Moravian Sabbatarians founded around 1528, the Seventh-day Baptists who arose in England from 1650 and the Seventh-day Adventists founded in the USA in 1863, to the Judaeo-Christian type the Transylvanian Sabbatians founded in 1588 and the Russian Subbotniki who appeared from 1640. The followers of the Jewish Messiah pretender Shabbtai Zvi, named after him, are distinguished from these. In the 90s of the last century, several Messianic Evangelical congregations arose in Germany that also celebrate the Sabbath.

Jesus' followers gather ears of corn from fields on the Sabbath. Caspar Luyken. Bowyer Bible in the Bolton Museum, England

Luis Ricardo Falero, 1878: Witches on the Way to the Witches' Sabbath

Meaning in Islam

In Islam, the Sabbath gave rise to a corresponding weekly rest period for the worship gathering (al-jumu'a) for the afternoon Friday prayer. It is assumed that Muhammad chose this day for this purpose because he had entered Mecca for the first time on this day and the seventh day was considered an unlucky day for him - possibly due to influences from Zoroastrianism.

Sura 62:9f. contains the commandment to do so:

"Believers! When the call to prayer is made on Friday (i.e. on the Day of Assembly), then turn with zeal to the remembrance of God and leave the business of buying (so long)! That is better for you, if (otherwise) you know (how to judge correctly). 10 But when the prayer is over, then go your ways (w. spread yourselves out in the land) and strive that God may show you favour (by pursuing your purchase)."

Accordingly, Muslims interrupt work on Friday only for the duration of the common prayer and continue it afterwards.

See also

- Scraper lid

- Jewish cemetery (Ebern), stylised Shabbat lamp on a gravestone

- Jewish Museum Westphalia, shows among other things an original Shabbat lamp, a link leads to a detailed picture

Questions and Answers

Q: What day is Shabbat?

A: Shabbat is the seventh day of the week, which is Saturday.

Q: When does Shabbat begin and end?

A: Shabbat begins when the sun goes down on Friday and ends after it gets dark on Saturday night.

Q: Where does the idea of Shabbat come from?

A: The idea of Shabbat comes from the Bible's story of Creation, where God creates everything in six days and rests on the seventh day.

Q: What language did "Shabbat" originate from?