Seven Years' War

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Seven Years' War (disambiguation).

Seven Years War

Clockwise, starting at the top left: Battle of Plassey, Battle of Fort Carillon, Battle of Zorndorf, Battle of Kunersdorf.

Clockwise, starting at the top left: Battle of Plassey, Battle of Fort Carillon, Battle of Zorndorf, Battle of Kunersdorf.

Seven Years' War (1756-1763)

European theater of war:

Pirna* - Lobositz* - Prague* - Kolin* - Hastenbeck** - Groß-Jägersdorf* - Moys* - Hastenbeck* - Roßbach* - Breslau* - Leuthen* - Rheinberg** - Krefeld** - Domstadtl* - Olmütz* - Mehr** - Zorndorf* - Saint-Cast - Hochkirch* - Bergen** - Kay* - Minden** - Kunersdorf* - Lagos*** - Hoyerswerda* - Bay of Quiberon*** - Maxen* - Koßdorf* - Landeshut* - Emsdorf** - Warburg** - Liegnitz* - Berlin* - Kloster Kampen** - Torgau* - Döbeln* - Vellinghausen** - Ölper** - Burkersdorf* - Reichenbach* - Freiberg*

(* Third Silesian War, ** Western theater of war - Great Britain/Kur-Hannover a. o. Allies against France, *** Naval battle)

American theater of war:

Seven Years War in North America

Monongahela - Carillon - La Belle Famille - Québec - Beauport - Abraham Plain - Sainte-Foy - Restigouche

Asian theater of war:

Third Carnatic War

Cuddalore - Negapatam - Pondicherry - Wandiwash - Manila

In the Seven Years' War from 1756 to 1763, all the major European powers of the time fought, with Prussia and Great Britain/Kurhannover on one side and the imperial Austrian Habsburg monarchy, France and Russia, and the Holy Roman Empire on the other. Medium-sized and small states were also involved in the conflicts.

The war was fought in Central Europe, Portugal, North America, India, the Caribbean and on the world's oceans, which is why historians sometimes regard it as a world war. While Prussia, Habsburg and Russia fought primarily for supremacy in Central Europe, Great Britain and France also fought for supremacy in North America and India. Although new strategies of warfare were established in the various theaters of war, the Seven Years' War is considered one of the last cabinet wars.

From a global perspective, it was about the geopolitical and power-political balance in Europe and the colonies assigned to it, about influence on the transatlantic sea routes, about domination over non-European bases, for example in Africa or India, and about trade advantages.

From the Prussian point of view, the Seven Years' War was also called the Third Silesian War; here, immediate territorial interests were initially in the foreground. In North America, the British spoke of the French and Indian War or Great War for the Empire, the French of La guerre de la Conquête. The British invasion of the Philippines in 1762 was called Ocupación británica de Manila from the Spanish perspective. The fighting in the Indian subcontinent is called the Third Carnatic War.

The wars ended in 1763, and the states involved concluded the Peace Treaties of Paris and Hubertusburg in February of that year. As a result, Prussia rose to become the fifth major European power, which deepened the dualism with Austria. France lost its dominant position in continental Europe and large parts of its colonial territories in North America and India to Great Britain, which thus finally became the dominant world empire.

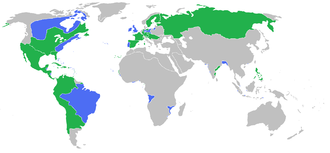

Alliances and territories of the participants of the Seven Years' War Great Britain, Prussia, Portugal and Allies France, Spain, Austria, Russia, Sweden and allies

Previous story

On October 18, 1748, the Peace of Aachen had ended the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) without eliminating the potential for conflict between the great powers. Thereafter, the following goals determined the foreign policy actions of the various states:

- Prussia had conquered the Austrian province of Silesia under Frederick II and tried to hold it against a possible reconquest by means of an alliance system.

- Austria under Maria Theresa pursued the goal of reconquering Silesia. To ensure success, Chancellor Wenzel Anton Count Kaunitz (1711-1794) first tried to isolate Prussian King Frederick II (1712-1786) in foreign policy terms.

- Russia, under the reign of Tsarina Elizabeth (1709-1762), was interested in expanding westward, with her sights set on Semgall and the Duchy of Courland. Both were under Polish suzerainty. In exchange for their cession to Russia, Elizabeth wanted to occupy Prussia (East Prussia) in order to offer it to Poland as a bargaining chip. Thus, the war against Frederick, for which Austria was looking for allies, came just in time for her.

- Great Britain saw France as its main rival and tried to weaken it, especially in the colonies. Since George II was also Elector of Hanover in personal union, he had to try at the same time to secure this rule against a possible French attack.

- France under Louis XV, for its part, saw Great Britain as its main adversary, but wished to delay a war in order to be better prepared.

In 1754, the Anglo-French conflict in North America came to a head when the first skirmishes occurred in the Ohio Valley (see: Battle of Jumonville Glen, Seven Years' War in North America). The British government sent a larger contingent of troops under General Edward Braddock (1695-1755) to the American colonies in January 1755, after which a French fleet also sailed in March. The summer of that year saw further fighting on land and sea, with a massacre of pro-French Indians of British troops at the Battle of Monongahela in July 1755 further escalating the colonial war between the great powers of France and Great Britain. In August, Britain began seizing French merchant ships.

Since war now seemed inevitable, both the French and British governments sought allies in Europe. France wished to avoid a pan-European war so that it could concentrate entirely on Britain. A defensive alliance with Prussia was already in place, but in August 1755 negotiations also began with Austria to keep it out of the incipient war. This greatly suited the diplomatic efforts of Count Kaunitz, whose goal was to disengage France from its alliance with Prussia.

Because Prussia had been allied with France in the War of the Austrian Succession, there was a danger that King Frederick II could have attacked the Electorate of Hanover, which was linked to Great Britain by a personal union. Therefore, on September 30, Great Britain concluded the Treaty of Saint Petersburg with Czarina Elizabeth of Russia, in which Russia undertook to position 50,000 men along the borders of East Prussia for four years. In return, the tsardom was to receive an annual payment of 100,000 pounds sterling and another 400,000 pounds if the Russian contingent was increased. According to the treaty, however, the Russian troops were only allowed to intervene militarily after the outbreak of hostilities on German soil. This move was intended to deter Prussia from attacking Hanover.

At the same time, however, Great Britain negotiated with Prussia. Prussia's intimidated monarch asked Great Britain to stop subsidies to the tsarist empire and to enter into a joint defense of Hanover against France instead. In the so-called Westminister Convention concluded on January 16, 1756, both powers agreed to protect northern Germany from foreign troops. From Frederick II's point of view, this agreement did not represent an affront to France because he still believed that France's main adversary was Austria. At the same time, he assumed that in this way he had ensured that Russian troops could not act against him without violating their treaties with Great Britain. For George II, on the other hand, the treaty with Prussia meant the protection of his ancestral lands.

At the court of Louis XV of France, the British-Prussian alliance was seen as a problem, because it prevented French troops from occupying Hanover. However, the Electorate was needed as a bargaining chip in a war against Great Britain. Under this impression, the Treaty of Versailles was concluded on May 1, 1756, a defensive alliance between Austria and France, also known as the "reversal of alliances" because of the centuries-long Habsburg-French antagonism. France would now no longer assist Prussia in a war against Austria. At the same time, Austrian diplomats had already established links with the Russian court in March/April of that year, where they ascertained a willingness for joint Austrian-Russian action against Prussia. Austrian diplomacy had thus succeeded in largely isolating Frederick II from Prussia. In a war planned for 1757 to regain Silesia, Austria did not need to engage in any other theater of war, but could count on the assistance of Russia and perhaps Saxony as well.

In the weeks that followed, the conflict escalated. As early as April 1756, a French unit, with the participation of Duke Ludwig Eugen von Württemberg, had captured the British island of Menorca and stationed troops on Corsica. This was followed by Britain's official declaration of war on France on May 17, 1756, to which the French court responded with its own declaration of war on June 9.

With the entry of Prussian troops into Saxony on August 29, 1756 - without a declaration of war - and the encirclement of the Saxon army near Pirna, which began three days later, the war also began on the European mainland.

Frederick II of Prussia, Portrait by Johann Georg Ziesenis, 1763

Maria Theresa of Austria, portrait by Martin van Meytens, c. 1759

Territorial war targets

In contrast to the "patriotic" Prussian and Austrian historiography, Prussia and Austria pursued territorial changes that went beyond a mere assertion or reclamation of Silesia. For Prussia, the occupation of Saxony played a key role - first and foremost as a goal for a possible annexation, but at least as a bargaining chip for other territorial gains. In exchange for French help in regaining Silesia (and the crushing of Prussia primarily sought by Maria Theresa), Vienna was willing to cede the Austrian Netherlands to a Bourbon collateral line (Bourbon-Parma) and to cede several barrier fortresses or barrier places there directly to France. France and Austria defined their exact expansionist desires and territorial exchanges only after the outbreak of war, in the second Treaty of Versailles (May 1, 1757) (see below). Any conquests made at the expense of Prussia or Great Britain, beyond the planned annexations, were to be shared among the allies, according to their share of the allied army contingent.

In the Third Treaty of Versailles (1758), however, France renounced all claims in the Austrian Netherlands. In return, it reduced its aid to Habsburg in order to concentrate entirely on the struggle against Great Britain.

Austria: Crushing of Prussia

Vienna intended a decisive weakening of its adversary, which was to be achieved by its territorial crushing. Accordingly, Prussia would have been reduced to its 1614 possessions, being left only with the Kurmark. Austria claimed Silesia, the County of Glatz and the Principality of Crossen as well as some as yet unspecified territories on the Bohemian-Prussian border. For Saxony, the principality of Halberstadt as well as the duchy of Magdeburg with the associated Saalkreis and the Immediatstadt Halle were intended. However, it was a condition that Saxony cede Upper and Lower Lusatia to Habsburg.

According to the preliminaries to the second Treaty of Versailles, Sweden was initially to receive back only all the territories of Swedish Pomerania that had been lost to Prussia (i.e. since 1679). In the final version finally signed, it was also promised Hinterpommern.

The Prussian exclaves of Cleves, Mark and Ravensberg (from the former United Duchies of Jülich-Kleve-Berg) as well as Obergeldern were destined for the Electoral Palatinate and the Republic of the Seven United Provinces (république de Hollande (sic)) (according to an as yet undetermined distribution key). The Tsarist Empire claimed East Prussia.

Russia planned to offer its new acquisition to Poland in exchange for Semigallia and the Duchy of Courland.

Prussia: expansion to the north, south and/or east

Already as crown prince, Frederick II had named the Polish Prussia royal share (from 1773 West Prussia), the Swedish Western Pomerania and Mecklenburg as targets of future acquisitions in a letter to his chamberlain Dubislav Gneomar von Natzmer in 1731. In his (first) Political Testament of 1752, he also referred to the possession of Saxony as a useful and greatest possible expansion.

The rapid occupation of Saxony and the first victories of 1756 and 1757 seemed to bring Frederick closer to this desire for annexation, but even after the reconquest of Saxony by Austria and its allies and after the defeat of Kunersdorf, Frederick stuck to the territorial plans formulated in his Political Testament. Instead of all of Saxony, he wanted to obtain at least Lower Lusatia in 1759 and compensate Saxony for it with Erfurt (which belonged to the Electorate of Mainz). Alternatively, he hoped at least for a claim for the seizure of West Prussia after the imminent death of the sick Saxon-Polish King August III. Only in the hopeless situation of 1761 did he offer an armistice and a peace without rounding-off demands on the basis of the pre-war possession status. Despite the peace achieved in 1763 without territorial acquisitions, Frederick also repeated the desired rounding off of Prussia with Saxony and West Prussia in his (second) Political Testament of 1768.

France: control of Belgium and annexation of British colonies

In the event that Silesia and Glatz actually returned to Austrian possession, France demanded the cession of the Belgian barrier fortresses of Ypres, Veurne (Furnes), Mons and Knokke (in the second Treaty of Versailles: Fort Quenoque), which were part of the so-called Pré carré, as well as the port cities of Ostend and Nieuwpoort (Nieuport), both of which France had already demanded to be handed over in advance as a pledge. At the same time, the Austrian garrison troops there would have been freed for the war against Prussia. After the end of the war, France was to be allowed, at its own expense, to grind down the fortifications of Luxembourg City (then belonging to the Austrian Netherlands). The rule over the Austrian Netherlands (and thus seat and vote in the Burgundian Imperial Circle and in the Imperial Diet) was to be given to the bourbon Philip of Parma. In return, his Italian possessions were to revert to the House of Habsburg, which had lost the duchies of Parma and Piacenza and Guastalla to the Bourbons in the Peace of Aachen (1748).

From Great Britain, France planned to acquire Gibraltar and Menorca (both for Bourbon Spain) as well as the Channel Islands of Jersey, Guernesey and Alderney (Origny and Aurigny, respectively). The Duchy of Bremen-Verden was to be seized from the British King (in his capacity as Elector of Hanover) and restituted (possibly under Danish suzerainty).

Great Britain: control of Belgium and annexation of French colonies

Like Prussia, Great Britain was not solely concerned with defending its possessions. In North America and India, it wanted to oust its French colonial rival once and for all. The fortress of Louisbourg and the neighboring city of the same name, as well as the Ohio Valley, were to become English at all costs. In addition, London wanted to prevent French influence from spreading to the Austrian Netherlands, whose ports were dangerously close to the British Isles, at almost any cost. Austria's refusal to reinforce its troops there at Britain's request had, after all, previously provided the reason for the dissolution of the Austro-British alliance on August 16, 1755.

The warring parties

Alliance A (Treaty of Versailles and extensions)

| Territory | from | to |

| "Imperial Army" or Habsburg Monarchy (Treaty of Versailles) | 1756 | 1763 |

| Kingdom of France (Treaty of Versailles) | 1756 | 1763 |

| Electorate of Saxony | 1756 | 1763 |

| Russian Empire | 1757 | 1762 |

| Holy Roman Empire: Imperial Execution by "Imperial Army | 1757 | 1763 |

| Kingdom Sweden | 1757 | 1762 |

| Kingdom of Spain ("Bourbon House Treaty" with France) | 1761 | 1763 |

| Duchy of Parma ("Bourbon House Treaty" with France) | 1761 | 1763 |

| Kingdom of Naples and Kingdom of Sicily ("Bourbon House Treaty" with France) | 1761 | 1763 |

Alliance B (Westminster Convention and Extensions)

| Territory | from | to |

| Prussia (Convention of Westminster) | 1756 | 1763 |

| Kingdom of Great Britain and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg ("Electorate of Hanover") (Convention of Westminster) | 1756 | 1763 |

| Kingdom of Portugal | 1756 | 1763 |

| Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel | 1756 | 1763 |

| Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel | 1756 | 1763 |

| Duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg | 1756 | 1763 |

| County of Schaumburg-Lippe (Bückeburg) | 1756 | 1763 |

History

The French army under Louis-Charles-Auguste Fouquet de Belle-Isle had already planned a double strategy in February 1756: on the one hand, an invasion of the British Isles was being prepared, and on the other hand, the Balearic island of Menorca, which had been awarded to Great Britain in the Peace of Utrecht that ended the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713, was to be attacked by sea. Under the nautical command of Lieutenant général des armées navales Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, twelve ships of the line, three frigates and a total of 173 transport units with 25 infantry battalions - all together in a troop strength of about 15,000 men - were assembled in front of the Castillo de San Felipe de Menorca at the Menorcan base of Port Mahon.

The attack on April 10, 1756 was entrusted to Marshal Louis François Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, his opponent was the Briton William Blakeney (1672-1761) with about 5000 men. Admiral John Byng, with a fleet of 17 ships, failed to break the siege ring in the naval battle off Port Mahon on May 10 of the same year. The French siege or conquest was successful - Blakeney was forced to surrender on June 28. Admiral Byng was court-martialed by the British and executed on March 14, 1757 for disobeying the Fighting Instructions. In the aftermath of the British defeat, Britain officially declared war on France on May 18, 1756.

In June 1756, Frederick II received knowledge of the rapprochement between France and Russia and of Russian troop movements through his spies at the European courts. He also received copies of the Paris and Petersburg treaties documenting the alliance between Austria, Russia, France, and Saxony. Frederick then ordered the mobilization of his regiments in East Prussia and Silesia to forestall the threat of attack from several sides by invading Saxony. The occupation of Saxony had a military and an economic background for Prussia (see Ephraimites and Leipzig Mint: Under Prussian Occupation). Militarily, Frederick II sought to gain a natural border wall to the Austrian province of Bohemia with the Ore Mountains and Saxon Switzerland. In addition, the occupation allowed Frederick to transport needed war materials, such as cannons, ammunition, etc. up the Elbe River from Magdeburg. Economically, prosperous Saxony was expected to fill the Prussian king's war coffers. After the swift occupation of Saxony, Frederick wanted to move into Bohemia. There, the capture of Prague was to allow the permanent placement of Prussian forces on enemy territory and force Maria Theresa to negotiate peace. With such a success, Russia could then no longer have been expected to attack Prussia alone the following year.

1756

Saxony/Bohemia

On August 29, 1756, the Prussian army crossed the border of Saxony without prior declaration of war. The Saxon army under the leadership of Count Rutowski was surprised and gathered in a camp near Pirna, where the Prussian army surrounded them on September 10 (Siege near Pirna). Already on September 9, the Prussian army had occupied Dresden without a fight. Rutowski, however, refused to surrender because he expected that the Austrian army would soon depose him. When the Austrian army under the command of Field Marshal Browne actually approached at the end of September, Frederick II went to meet it with half of his army (the other continued to besiege the Saxon army camp). On October 1, 1756, the battle of Lobositz in Bohemia took place. The battle ended with a Prussian victory, which prevented the Austrians from reaching the enclosed Saxons. As a result, the Saxon troops were forced to surrender on October 16, 1756. They were initially pressed into Prussian service, but most of them deserted the following spring. Thus, only the occupation of Saxony had been achieved, while the concept of a decisive strike against Austria had failed.

North America

→ Main article: Seven Years' War in North America

The British-French antagonism in the North American colonies had already led to major fighting the previous year. In 1756, the French under Marquis de Montcalm took the offensive. On August 15, 1756, they captured the important British Fort Oswego, bringing the entire Lake Ontario area under their control. Regular units manned the French forts, leaving only militia and warriors of allied indigenous Indian tribes available for further offensive operations. Therefore, further French action was limited to small-scale warfare, while the British rallied their troops, but without becoming offensive themselves.

1757

The situation was unfavorable for Frederick II at the beginning of 1757. On January 17, the imperial war against Prussia was declared, as the latter had committed a breach of the peace by attacking Saxony. The imperial troops would thus enter the scene as another opponent of Prussia. Only days later, on January 22, Russia and Austria signed an alliance treaty, which was followed by a Franco-Austrian offensive alliance on May 1. So, in addition to the long-awaited attack by the Russians and the war against Austria, troops from France, as the guarantor power of the Peace of Westphalia, would move into Germany to take action against Prussia while gaining Hanover as a pawn in the war against Britain. The British were under pressure in North America and India and could hardly provide effective protection for Hanover. For this reason, the German principalities allied with Prussia and Britain raised an army, called the Army of Observation, to operate against the French forces. At the same time, France began to obligate several German principalities to provide auxiliary troops by means of subsidence treaties. Initially there were about 6800 Bavarian, 4000 Württemberg, 6000 Electoral Palatine and 1800 Electoral Cologne troops. In the course of the war, some states agreed to repeatedly provide additional soldiers. These auxiliary troops were under French supreme command and existed alongside those district troops which the states concerned had already seconded to the Imperial Army. In addition, 20,000 Swedes were financed. A special case was formed by those approximately 10,000 Saxon troops who had been pressed into Prussian service at Pirna in 1756, but had fled at the first opportunity. They gradually joined the "rallying force" in Hungary, under the command of Franz Xaver of Saxony, as so-called reverts, and were used against British troops in western Germany. The deployment against Prussian troops was avoided, as it was feared that the revertents would otherwise face severe punishment as deserters if they were captured. The 12 battalions formed from the reverts continued the tradition of their parent units, which had fallen into Prussian captivity in 1756. In 1758, France took the corps into its pay for the first time. The contract was for one year at a time, but was regularly renewed, most recently in 1762. On March 23, 1763, the troops began their march back to Saxony.

Bohemia/Silesia

Frederick II revisited his strategic concept of the previous year to first take Prague and thus strike a decisive blow against Austria. In April, Prussian troops entered Bohemia from several sides, where the Battle of Prague took place on May 6, 1757. Although the Prussians were victorious, a large part of the Austrian army saved itself in the fortress. While Frederick began the siege of the fortress, an Austrian relief army under Field Marshal Count Daun approached from the south. Frederick II opposed it with half of his troops (the other besieged Prague) in the Battle of Kolin on June 18, but was severely defeated. As a result of this defeat, the Prussians had to vacate all of Bohemia and retreat to Saxony. In the months that followed, the opposing armies maneuvered around each other without result until Frederick II was forced by the approach of the Imperial Army in Thuringia to hurry there with a large part of his forces. The Austrians, now superior, attacked the Prussian troops under the Duke of Brunswick-Bevern at the Battle of Moys on September 7 and forced them to retreat. After another battle of Breslau on November 22 and the capture of the fortresses of Schweidnitz and Breslau, most of Silesia was once again under Austrian control by the end of November. During this period, Austrian General Andreas Hadik von Futak also managed with a detachment of hussars to occupy Berlin for one day (October 16) before retreating. However, in early December the main Prussian army under Frederick II arrived in Silesia again. He attacked and decisively defeated the Austrian army at the Battle of Leuthen on December 5. The latter retreated to Bohemia, while the Prussians recaptured the Silesian fortresses by April 1758. Thus, the initial situation from the beginning of the year was largely restored.

Central Germany

In June, the French also attacked. They sent an army to northern Germany, which occupied the Prussian lands on the Rhine and then proceeded against Hanover. In the following year, Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel had separate copper coins minted for payment transactions with the French occupying troops. On July 26, 1757, French troops led by Marshal d'Estrées defeated the Army of Observation under the Duke of Cumberland, which consisted of contingents from the small German states, in the Battle of Hastenbeck. The Army of Observation retreated to the North Sea, where it declared itself neutral in the Convention of Zeven Abbey. This left the way open for the French to reach Berlin in late summer. But since they had no interest in weakening Prussia too much vis-à-vis Austria, they contented themselves with occupying the principalities allied with Prussia. Marshal d'Estrées was replaced by the Duke of Richelieu after some intrigues in Versailles.

At the same time, in August, the Imperial Execution Army also began its operations in Thuringia against the Saxon territory. The army consisted of a French corps under the Prince of Soubise and the imperial troops under the Duke of Saxe-Hildburghausen, who was also the commander-in-chief. It was against this army that Frederick II of Silesia advanced, and on November 5, 1757, he defeated it devastatingly at the Battle of Roßbach. The imperial army did not appear as an independent unit in the following years. Frederick II set off again for Silesia with the main Prussian army to counter the Austrian advance there (→ see above).

East Prussia

Frederick II had assigned the experienced Field Marshal Johann von Lehwaldt with 30,000 men to defend East Prussia. On July 1, a Russian army of about 100,000 men under General Stepan Fyodorovich Apraxin attacked. It captured the fortress of Memel on July 5 after a short siege. The next objective was Königsberg. Lehwaldt opposed the Russian advance at the Battle of Groß-Jägersdorf on August 30 and was defeated. However, the Russian supply situation was so bad without the port of Königsberg that Apraxin withdrew from East Prussia again. Only in Memel a garrison remained.

Baltic coast

Sweden had joined the anti-Prussian coalition in 1757 and made unsuccessful efforts to retake Szczecin until the end of the war. The fighting in the theater of war in Swedish Pomerania, Prussian Pomerania, northern Brandenburg and eastern Mecklenburg, which never resulted in a battle, was referred to by the Swedes as the Pommerska kriget (Pomeranian War).

On September 12, 1757, the Swedish army attacked Prussia from Stralsund. They captured the weakly defended towns of Pasewalk, Ueckermünde and Swinemünde. As a result, Frederick II ordered Lehwaldt's corps from East Prussia to operate against the Swedes. Lehwaldt captured Wollin, Anklam and Demmin by the end of the year and remained in Western Pomerania while the Swedes retreated to Stralsund.

North America

Marquis de Montcalm continued his strategy of destroying the main British forts in order to forestall a British offensive from these forts. The target of the attack was Fort William Henry on Lake George. The British surrendered after a few days of siege on August 9 in exchange for free passage. The French's Indian allies did not abide by the agreements and ambushed the British troops, which became known as the Fort William Henry Massacre. Meanwhile, the British were massing troops on Cape Breton Island for an attack on Fort Louisbourg, which was postponed.

1758

In January, Russian troops under Count Wilhelm von Fermor conquered East Prussia, which had been all but abandoned by Lehwaldt's recall. Fermor took over the administration as governor-general and the country took an oath of allegiance to Empress Elisabeth. In August he advanced into the Neumark, intending to unite with the Austrians who were advancing from Bohemia. Frederick was able to prevent this at the Battle of Zorndorf. The Russians retreated behind the Vistula River into East Prussia by the end of the year. Their retreat caused Sweden to abort its incursion into the Mark Brandenburg. Taking advantage of the absence of the main Prussian contingent, Austrian troops managed to occupy almost all of Silesia.

Frederick II planned to open a way into the Austrian heartland with the surprise siege of Olomouc. Thanks to the reinforced walls since the War of the AustrianSuccession, the Austrians were able to successfully defend the fortress of Olomouc, unlike in 1741. During the raid at Domstadtl in June, they destroyed a large Prussian supply convoy for the siege army's supplies. This forced the Prussians to lift the siege and withdraw from Moravia.

In addition, in late summer Austrian troops under Count Leopold Joseph von Daun invaded southern Saxony, defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Hochkirch, and attempted to take Dresden, but failed. At the end of November they retreated to Bohemia.

Britain promised Prussia financial resources of 4.5 million talers and the establishment of a new army in Electoral Hanover in an agreement of April 11, 1758. Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was able to defeat the French at the Battle of Rheinberg on June 12, 1758, and at the Battle of Krefeld on June 23, 1758, and by the end of the year controlled all of the territory on the right bank of the Rhine.

In North America, the French defeated a vastly outnumbered British army at the Battle of Ticonderoga on July 18, 1758.

In the Battle of Mehr (now Mehrhoog) on August 5, 1758, 3,000 Prussians under General Philipp von Imhoff defeated nearly 10,000 French. The battalion Stolzenberg hit the French in the flank. To this day, an obelisk commemorates this battle there (inscription: "Germany's brave warriors who defeated the French here under General von Imhoff on August 5, 1758."). Erected on August 5, 1858 by the inhabitants of Haffen and Mehr"). The French army fled back to the town of Wesel, which it had occupied.

1759

After the high blood toll of the previous years of war, Prussia was no longer capable of offensive action; rather, it had to contend with attacks on the Prussian heartland. Once again, the Russians under Saltykov and Austrians under Leopold Joseph Count Daun tried to unite their forces to defeat Frederick together. This time this unification succeeded at the village of Kunersdorf (east of Frankfurt (Oder)), after the Russians had advanced from East Prussia - a Prussian unit that had opposed them had been defeated at the Battle of Kay on July 23 - and the Austrians had advanced via Silesia. Frederick suffered a catastrophic defeat in an attack on the camp of the now allies at the Battle of Kunersdorf (August 12); the Prussian army disbanded in the meantime.

However, due to growing contradictions within the alliance, the Russians, Austrians and French did not seize the opportunity to advance to Berlin. Frederick described this circumstance, which saved the Prussian state's existence, as the "miracle of the House of Brandenburg" in a letter to his brother Heinrich. The Russians retreated to their initial positions in the fall, and the Austrians withdrew to the Saxon theater of war. There, in the summer, the Imperial Army, taking advantage of the absence of Prussian troops, had occupied almost all of Saxony, including Dresden. After the unification of the Imperial Army with the Austrians, there was an encounter with a Prussian contingent here on November 20 in the battle of Maxen, in which the Prussian troops were encircled. The Prussian General von Finck surrendered a day later and was taken prisoner with about 14,000 men.

In the West German theater of war, the status quo remained largely intact until the end of the year; the French repulsed an advance by the Duke of Brunswick toward the Rhine in the Battle of Bergen on April 13. On August 1, the Prussian allies repulsed an advance of the main French contingent into Hanover at the Battle of Minden. After their heavy defeat, the French troops retreated; in the process, they suffered further defeats. France had no bargaining chips to trade for its occupied colonies in the peace negotiations at the end of the war.

The French suffered further decisive defeats in the naval battle of Lagos, in September with the loss of Québec (→Battle of Abraham Plain), and in November in the naval battle in the Bay of Quiberon. The year 1759 was therefore also known in Great Britain as the "Annus mirabilis."

On October 12, 1759, a preliminary agreement on the exchange of Russian and Prussian prisoners of war was signed in Bütow, in Hinterpommern.

1760

In 1760, Prussia was again primarily concerned with holding its own territories as well as those it had conquered, in view of its own weakness. The allied troops in the west, which had been very successful in 1759, had to support the Prussians with 10,000 men against the imperial army until early February; this weakened Duke Ferdinand against France.

Austria first wanted to regain Silesia and, together with the Russians, destroy the Prussian forces. Accordingly, Austrian troops under von Laudon invaded Silesia, captured important fortresses and defeated a Prussian corps at Landeshut. At the same time, Frederick unsuccessfully attempted to recapture Dresden with strong forces, resulting in considerable destruction of the city center.

The French victory on April 28 against the British at Quebec in the Battle of Sainte-Foy did nothing to change the foreseeable overall French defeat in Canada.

In western Germany, the Allies were still in winter quarters only in eastern Westphalia with very reduced forces. The French were in the Lower Rhine and southern Hesse. It was not until June that the French corps united in Hesse-Kassel. The Allied defeat at Korbach was matched by a French loss at Emsdorf. Despite the victory of the Allied troops at Warburg in Paderborn, the French held their ground in Hesse-Kassel.

When Austrian relief troops under Daun moved toward Dresden and Frederick was alarmed by developments in Silesia, he withdrew there and Daun followed him. Both Austrian armies, attacked by Frederick on August 15, managed to unite at Liegnitz. The Prussian troops managed to win and thus link up with troops under Prince Henry, who was thus able to keep the Russian forces at a distance.

These successes were quickly put into perspective, as Prussia's opponents simultaneously succeeded in recapturing Saxony by the Imperial Army and briefly occupying Berlin by the Russians under Tottleben and Chernyshev and Austrians under Lacy. Frederick once again managed to strike a liberation blow at the Battle of Torgau on November 3, defeating the Austrian forces under Daun that followed him and pushing them back into Saxony. Nevertheless, Prussia's situation was catastrophic, with East Prussia, Saxony and Silesia, among others, in the hands of the enemy.

Swedish troops simultaneously established themselves in the Prussian part of Western Pomerania. In the fall, Allied troops were defeated by the French on the Rhine in the Battle of Kloster Kampen.

1761

Silesia was once again the theater of war. Against the advancing and uniting Austrians (under Laudon) and Russians, Frederick II moved into an entrenched camp near Bunzelwitz. The Prussian army stood with 50,000 soldiers against 132,000 soldiers of the allied Austrians and Russians. Frederick II made intensive efforts to form an alliance with the Turkish Empire directed against Russia and Austria. At the outbreak of the war, as in the previous year, he had sent Gottfried Fabian Haude, an expert on Turkey, to Istanbul under the assumed name of "Geheimer Kommerzienrat Karl Adolf von Rexin" for the purpose of concluding a trade and defensive treaty. In 1761, despite negotiations for a military alliance, the latter only achieved the conclusion of a "friendship and trade treaty" with Prussia.

The camp of Bunzelwitz could be held all summer against the allies struggling with supply difficulties. The Russians left in September, worn down, but so did the Prussians, so that the important fortress of Schweidnitz, together with Upper Silesia, fell into the hands of the Austrians.

In Hinterpommern, the Russians captured Kolberg, but in Vorpommern, the Prussians managed to hold their own against the Swedes. Little happened on the West German theater of war, due in particular to the waning strength of the French state.

Thus, Prussia was lucky this year that its opponents were not able to strike a decisive blow. Nevertheless, Prussia's situation remained critical. In addition, the British government stopped subsidy payments after the fall of William Pitt in December.

1762

Frederick gained relief from an event that is often mistakenly associated with his then already two-year-old phrase about the "miracle of the House of Brandenburg." After the death of Tsarina Elizabeth on January 5, her nephew, an admirer of Frederick, succeeded to the throne as Peter III. After receiving the Prussian Order of the Black Eagle and other honors, he concluded the Peace of Saint Petersburg with Prussia on May 5 and returned the kingdom. On May 22, Sweden joined in the Peace of Hamburg. Tsar Peter III followed up the peace with an alliance with Prussia on June 1. The Russian corps, which had then joined Frederick at the end of June, was ordered to withdraw by his successor, Empress Catherine II, after Peter III's assassination on July 17. She left the peace in force, but not the alliance. Strengthened by the freed forces, Frederick succeeded in ousting the Austrians from Silesia and Saxony. He defeated Daun, who was unaware of the Russians' neutralization, at Burkersdorf on July 21 and was able to occupy Schweidnitz. The final battle between Austria and Prussia took place at Freiberg on October 29, 1762. The Prussians under Prince Henry were victorious, thus succeeding in reclaiming Saxony.

On November 24, 1762, through Saxon mediation, an armistice ended the fighting between Prussia and Austria.

In the summer, French troops advanced into northern Hesse for the last time, but were defeated with heavy losses on June 24 in the Battle of Wilhelmsthal (today part of the municipality of Calden) and on July 23 in the Battle of Lutterberg, with theaters of war on this side and on the other side of the Fulda near Lutterberg (today part of Staufenberg in Lower Saxony) and near Knickhagen (today part of the municipality of Fuldatal) on the Fulda tributary Osterbach. A final attempt to push through to Hanover via northern Hesse failed at the Battle of Brücker Mühle on September 21, 1762, when the French were prevented from crossing the Ohm near Amöneburg.

On the Iberian Peninsula, a Spanish invasion of Portugal (Guerra Fantástica) failed: In May, Spaniards had invaded northern Portugal from Galicia and occupied Bragança; troops advancing from Zamora captured the Portuguese border town of Almeida in August. In turn, the Portuguese, reinforced by a British contingent under Count Wilhelm von Schaumburg-Lippe, occupied the Spanish border town of Valencia de Alcantara. Overseas, two key strategic Spanish positions fell to the British after the siege of Havana and the capture of Manila. After further smaller, mostly unsuccessful attacks by both sides, an armistice was agreed between Spain, Portugal and Britain in late November 1762.

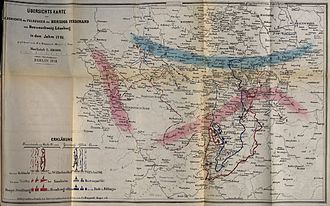

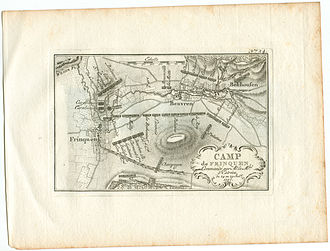

Outline map of the history of the campaign of Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel in 1762

Battle near Koßdorf

Reverse of the 1 denier of 1758

1 Denier = 1/13 Mattier from Br.-Wolfenbüttel for payment transactions with French. Occupation troops

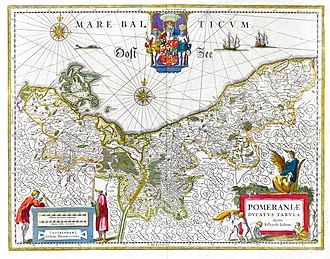

Historical map of the Duchy of Pomerania from the 17th century

French troop camp on July 24 and 25, 1757 on the Weser River, immediately before the Battle of Hastenbeck. Engraving "No. 24" by Jakobus van der Schley

August Querfurt: Battle of Kolin (Museum of Military History Vienna)

Military operations in Europe in 1757

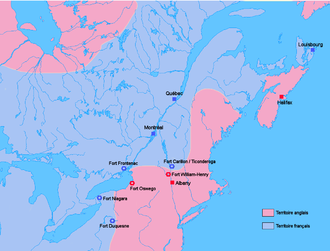

English and French territory in North America before the start of the war

Military operations in Europe in 1756

The departure of the French fleet for the invasion of Port Mahon on April 10, 1756, by Nicolas Ozanne

The Battle of Menorca, Bataille de Minorque (1756), on May 20, 1756. La Galissonière was victorious in this battle, John Byng retreated.

Europe at the time of the Seven Years' War

The war in the colonies

Under Robert Clive, the British conquered the French possessions in India (→ Third Carnatic War). The war thus also took place on the Indian subcontinent, or more precisely: between the troops of the British East India Company and French forces.

In North America, hostilities (→ Seven Years' War in North America) began as early as 1754. After initial setbacks (French victory at the Battle of Monongahela in 1755), the British first conquered the Ohio area, then advanced to the Great Lakes and finally began the invasion of Canada. The destruction of the French fleet in two naval battles cut Quebec off from Europe. The British then conquered Québec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760.

On September 23, 1762, British troops landed in Manila and began the British invasion of the Philippines. In the ensuing battle for Manila, large parts of the city fortress of Intramuros were destroyed. The British operation did not end until February 1764, when Manila was returned to the Spanish. In the Ilocos region, in the northwest of the country on the main island of Luzon, native rebels under Diego Silang took the opportunity to revolt against the occupation.

Great Britain captured the trading settlements in French Senegal on April 30, 1758, during the Seven Years' War. On September 24, 1762, it concluded a preliminal peace with France at Fontainebleau without having consulted Prussia - an open violation of the Westminster Convention. Great Britain had dropped its continental dagger.

The peace treaties of 1763

Great Britain and Portugal concluded the Peace of Paris with France and Spain on February 10.

On February 15, 1763, Prussia concluded the Peace of Hubertusburg with its adversaries Austria and Saxony. Prussia's King Frederick II the Great signed the Final Act of the Seven Years' War Peace Agreement on February 21, 1763, at Dahlen Castle, where he resided during the negotiations. The status quo ante bellum was restored.

Impact

Political consequences

As a result of the war, Prussia had established itself as the fifth great power in the European concert of powers. The opposition to Austria that had begun with the Silesian Wars remained fundamental for German politics until the War of 1866 (German Dualism), apart from the phase of common opposition to Napoleon, and soon led to the War of the Bavarian Succession.

France, heavily indebted as a result of the war, failed to acquire the Austrian Netherlands (now Belgium), which Austria had pledged as compensation for helping to regain Silesia. The peace provisions further entailed the loss of most of the first French colonial empire. Thus, all North American possessions east of the Mississippi and all Indian possessions and zones of influence had to be ceded to the British except for isolated settlements. The resulting French revanchism was one reason for the support of the rebellious colonies in the American War of Independence. Last but not least, the unmanageable national debt in France since the Seven Years' War was also one of the causes for the outbreak of the French Revolution.

Since the war, Great Britain had become increasingly involved in European continental politics. In North America, the newly acquired territories between the Allegheny Mountains and the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers were not opened for settlement in order to protect the North American Indian societies living there and allied with Great Britain in the war. This, and the new taxes by which the settlers in the colonies were to share in the costs of the war, led to conflicts with the colonial power that eventually culminated in the American War of Independence.

According to historian Ute Planert, German nationalism emerged in the years of the Seven Years' War and afterwards, even though a German nation did not yet exist. The fatherland (under which Enlightenment thinkers such as Thomas Abbt (1738-1766) regarded Prussia) had been constructed as an "exclusive and homogeneous community" that could claim to be superior to other communities such as religion or family and that henceforth was regarded as the supreme instance of legitimacy.

Economic consequences

For the population of the participating states in the war zones, the war had partly catastrophic consequences. The loss of soldiers was immense - Prussia alone lost 180,000 men. The civilian population was also decimated, especially in the hardest hit areas such as Saxony and Pomerania. Saxony, as a Prussian-occupied territory, also suffered greatly from looting, forced recruitment and tribute payments.

For the Kingdom of Great Britain, war expenditures were put at 161 million pounds (equivalent to 1932 million livres), for France 700 million livres, and for Prussia 120 million Reichstaler (equivalent to 360 million livres) were calculated.

Étienne de Silhouette was the French controller general of finances, contrôleur général des finances under Louis XV. He held this administrative position from March 4 to November 21, 1759. He was supposed to put the finances, which had been shattered by the Seven Years' War, back in order. However, after introducing taxes on land and other signs of wealth for rich nobles - the nobility and the church were not taxed at the time - cutting nobles' pensions, as well as enforcing other measures such as melting down gold and silverware under martial law, he reaped fierce opposition and was relieved of his post again on November 21, 1759. His successor in office was Henri-Léonard Bertin.

With the beginning of the war, a vingtième or twentieth was instituted in France for a second time. Originally introduced by the contrôleur général des finances Jean Baptiste de Machault d'Arnouville, it was a direct tax of the absolutist ancien régime. During the war, a third vingtième was introduced in 1760. At the end of the war in 1763, the last vingtième was dropped, while the other two were replaced.

The Seven Years' War, according to Jacques Necker, later Finance Minister under Louis XV and Director General of Finance, plunged the Kingdom of France into insolvency after three years of fighting (October 1759).

Population policy implications

Although the Seven Years' War was not one of the longest-lasting military conflicts, there was an enormous loss of life. For the European theater of war alone, a total of 550,000 people were recorded as having died or been mortally wounded in the fighting. If one breaks down the numbers of fallen war participants by individual nations, the figures are 180,000 for Prussia, 140,000 for Austria, 120,000 for Russia, 70,000 for France and 40,000 for the Kingdom of Great Britain and the remaining nations, such as the German principalities, Sweden, Spain and Portugal. In contrast, the figures for noncombatant participants, or civilian populations, were about 320,000 for Prussia and 160,000 civilians for Austria. The population losses were quickly compensated for in Prussia, and by 1767 the population was already 111,000 higher than before the war. This was due to the high birth rate, the return of war refugees and deportees, and the influx from abroad, which was encouraged by the government as part of its peupling policy.

The begging soldier woman , copperplate engraving by Daniel Chodowiecki, 1764

Reception in art

Numerous compositions were written for the peace celebrations of 1763. For example, an oratorio-like "Sing-Gedicht" by Georg Philipp Telemann, which was performed "bey dem Hamburgischen Friedens-Feste," has survived with the title Gott, man lobt dich in der Stille (TVWV 14:12). On the occasion of the Peace of Paris, the comedy poet Charles-Simon Favart wrote the play Der Engländer in Bordeaux (The Englishman in Bordeaux), commissioned by the French Foreign Minister, which was first performed in March.

In 1763 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing began writing the comedy Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück, which was published and performed in 1767. The play is set in the period immediately after the war and deals with the fate of a soldier.

The plot of James Fenimore Cooper's novel The Last of the Mohicans, published in 1826, is set in North America at the time of the so-called Fort William Henry Massacre in 1757. The painter Benjamin West created one of the most famous depictions of the Seven Years' War in the visual arts with the history painting Death of General Wolfe (1770).

The title character of William Makepeace Thackeray's novel The Memoirs of Squire Barry Lyndon (from 1844) gets caught up in the turmoil of the Seven Years' War as a British mercenary. Stanley Kubrick adapted the novel into a film in 1975 (Barry Lyndon).

The artist Adolph Menzel passed down views of the mortal remains of fallen officers of the war. His portraits of corpses, created in 1873 on the occasion of the opening of the burial vaults under the Garrison Church in Berlin, show, among others, the mummified body of Field Marshal James Keith.

The feature films Fridericus - Der alte Fritz (1937) and Der große König (1942), both made for propaganda purposes during the National Socialist era and starring Otto Gebühr as Frederick II, glorify the Prussian king and portray the Seven Years' War from a Prussian perspective.

Battle of the Plains of Abraham: Death of General Wolfe. Painting by Benjamin West, 1770.

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the duration of the Seven Years' War?

A: The Seven Years' War lasted from 1756 to 1763.

Q: Who were the main powers involved in the war?

A: Most of the great powers in Europe were involved in the war, including Britain, France, Prussia, Austria, Russia, and Sweden.

Q: What caused the war?

A: An important cause of the war was the War of Austrian Succession.

Q: How is this conflict known in different places?

A: In the United States it is called the French and Indian War. In French Canada it is called the War Of Conquest. In both Sweden and Prussia it was called Pomeranian War because they were fighting over Pomerania. In India it is known as Third Carnatic War and for Prussia-Austria conflict it is called Third Silesian War.

Q: What type of interests opposed each other during this period?

A: The trade interests of British Empire were opposed to those of Bourbons who ruled France and Spain while Hohenzollerns who ruled Prussia fought with Habsburgs who were Holy Roman Emperors and archdukes in Austria mainly over Silesia.

Q: Was colonialism common at that time?

A: Yes, colonialism was common at that time.

Q: Who formed an Anglo-Prussian camp during this war? A:The Anglo-Prussian camp was formed by some smaller German states and later Portuguese Empire which fought against Austro-French camp allied with Sweden, Saxony and later Spain.

Search within the encyclopedia