Second Sino-Japanese War

Second Japanese-Chinese War

Part of: World War II (Pacific War)

Japanese during an attack on Chinese positions, Battle of Changsha (1941)

Second Japanese-Chinese War (1937-1945)

1937-1939Marco Polo Bridge

- Beijing-Tianjin - Chahar - Shanghai (Sihang Warehouse) - Beijing-Hankou Railway - Tianjin-Pukou Railway - Taiyuan (Pingxingguan, Xinkou) - Nanking - Xuzhou (Tai'erzhuang) - Henan - Lanfeng - Amoy - Wuhan (Wanjialing) - Canton - Hainan - Nanchang - (Xiushui) - Chongqing - Suixian-Zaoyang - (Shantou) - Changsha (1939) - South Guangxi - (Kunlun Pass) - Winter Offensive - (Wuyuan)

1940-1942Zaoyang-Yichang

- Hundred Regiments - Central Hubei - Southern Henan - Western Hebei - Shanggao - Shanxi - Changsha (1941) - Changsha (1942) - Yunnan-Burma Road - Zhejiang-Jiangxi - Sichuan

1943-1945West Hubei

- North Burma and West Yunnan - Changde - Ichi-gō - Henan - Changsha (1944) - Guilin-Liuzhou - West Henan and North Hubei - West Hunan - Guangxi (1945) - Manchukuo (1945).

The Second Sino-Japanese War (or Second Sino-Japanese War) is the name given to a full-scale invasion of China by the Japanese that began on July 7, 1937 and lasted until September 9, 1945. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, U.S. entry into the war, it was a theater of the Pacific War and thus part of World War II.

In the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China, "Anti-Japanese War" (Chinese 抗日戰爭 / 抗日战争, pinyin kàngrì zhànzhēng - "War of Resistance against Japan") is the official name of the war. However, this name is also used in other Southeast Asian countries for their own resistance to Japanese occupation. In China, the war is also known simply as the "War of Resistance" or "War of Resistance" (抗戰 / 抗战, kàngzhàn).

In Japan, the war is known as the Sino-Japanese War (Jap. 日中戦争, Nicchū Sensō) or HEI, Operation C or Invasion of China. In the Western world, the term Second Sino-Japanese War is also common.

Background

Political history

After the First Sino-JapaneseWar of 1894-1895, the Empire of Japan annexed Taiwan. In the Treaty of Shimonoseki, the European powers brokered peace between the Empire of China and the Empire of Japan. Although Japan had hoped to gain greater influence in Manchuria, the Russian Empire prevailed and was granted the concession for the Manchurian Railway and Port Arthur as a leased port. Japan's interest in Manchuria, which was rich in raw materials, was opposed to Russian interests, and so the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, which Japan won. Russia had to give up Manchuria, and Japan built the South Manchurian Railway, protected by the Kwantung Army, to transport raw materials to Korea. Korea became a Japanese protectorate in 1905 and was annexed in 1910.

The Great Depression of 1929 had also severely affected Japan. Many politicians and military officers saw a solution to the economic crisis in an intensification of colonial efforts. These were directed primarily against Manchuria.

In order to create a pretext for the invasion of Manchuria, agents of the Kwantung Army (Doihara Kenji, Amakasu Masahiko) blew up the line of the South Manchurian Railway near the town of Mukden on September 18, 1931. The Japanese military then blamed China for the damage to the railway line. After this so-called Mukden Incident, Manchuria was occupied by the Japanese army. There was no coordinated resistance from the Chinese, as the country was in the middle of the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang and the Communists. Individual Chinese warlords resisted the Japanese unsuccessfully. Japan established the puppet state of Manchukuo to administer the occupied territories. The Japanese army and navy were directly under the Emperor, and by this time had largely escaped parliamentary and government control, and were proceeding on their own in China. After its success in Manchuria, the military was able to justify this policy in retrospect, gaining more and more influence over Japanese policy.

China fought back with a trade boycott against Japan and refused to unload the cargo of Japanese ships. As a result, Japanese exports fell to one-sixth. This inflamed the mood in Japan. One incident in particular, in which five Japanese monks were mistreated in Shanghai in 1932 (one monk later succumbed to his injuries), was picked up by the Japanese media and fueled anger among the Japanese population. On January 29, Japan then bombed China and the First Battle for Shanghai ensued, where the first area bombardment against a civilian population occurred. Estimates put the death toll at around 18,000 Chinese and 240,000 homeless. China was forced to lift its trade boycott. A demilitarized zone was established around Shanghai. In May 1932, the two parties agreed to a truce, but the Japanese continued their advance. In 1933, the provinces of Roe and Chahar were occupied, and in 1935 China had to agree to a buffer zone between Manchukuo and Beijing, where the Japanese set up the Autonomous Military Council of Eastern Hopei (Hebei), composed of collaborating Chinese military officers. In 1936, parts of Inner Mongolia were occupied.

When the League of Nations protested the Japanese action, Japan withdrew from the League. Here, for the first time, it became apparent that the League of Nations had no means to end or prevent armed conflict.

In 1936, Japan and the German Reich signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, which was directed against the Communist International (Comintern). This pact had mainly symbolic significance. In 1937 Italy and during the Second World War other European states joined the pact.

There were repeated attacks by the Japanese on the Chinese civilian population. The Chinese expected Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek to intervene. But he concentrated on the fight against the communists and let the Japanese for the time being to spare his troops. His motives are disputed among historians. Some suggested he feared the Japanese army, others suspected him of collaborating with the Japanese. On the other hand, he saw the Communists as the greater danger in the struggle for China. Only when he was kidnapped by his own commanders Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng (Xi'an Incident), he gave in to the demand and signed a truce agreement with the communists. As a result, the second united front of the Nationalists and Communists was formed; this time against the Japanese.

Military balance of power and planning

Parts of the leadership of the Chinese national movement had been convinced since the 1920s that a war against Japan in China was inevitable due to the diverging interests of the two governments. Chiang Kai-shek countered the aggressive land-grabbing policy of the Japanese in northern China with appeasement in order to consolidate his own state and military. Chiang, with the help of the German military mission in China, pushed ahead with the modernization of the Goumindang forces beginning in 1933. A plan presented by the head of the German military mission, Hans von Seeckt, in 1935 called for the construction of a modern, mobile, and unified Guomindang army, comprising some 60 divisions, to be completed by 1938. Before the war began, the Nationalists had about 19 divisions with about 300,000 soldiers trained according to the specifications of the military mission. In addition, the plan called for streamlining and downsizing the divisions to free up more funds for equipment and modernization. Ten of these reformed divisions were raised before the war. Because of the lack of an industrial base, motorization and mechanization were abandoned. There were only about 3,000 motor vehicles in military use in all of China in 1937. The air force of the Republic of China at the beginning of the war comprised about 300 aircraft.

In 1935, Chiang formulated a national defense strategy against Japan. In view of China's military weakness, but also its larger area, wealth of resources and population, Chiang announced a defensive war of attrition, which would take place primarily in northern China and the country's coastal areas. To this end, the Guomindang Army sought to create the necessary infrastructure in the Chinese hinterland to sustain it. With regard to the production of ammunition for infantry weapons, China had sufficient domestic production. There was a distinct production shortage of artillery pieces and heavy weapons. The resulting dependence on foreign ordnance sourced from various nations created very serious logistical problems here. Domestically produced models such as mountain guns were of inferior quality and performance, which significantly limited their tactical use. Similarly, indigenous weapons production was not standardized, which in turn multiplied logistical problems. The Chinese state spent the majority of its national budget on the military in 1937, at 65%. The implementation of the rearmament plan was incomplete due to financial problems, political instability and lack of industrial capacity in the country. In particular, the modern training and exercise of troops could only be implemented to a fraction.

The Japanese Army in 1937 peacetime strength was about 247,000 soldiers and officers, divided into 17 divisions. In addition, there were four independent tank regiments. Full motorization and mechanization of the force was not possible due to the lack of an industrial base. Most of the transport and logistical tasks were performed by pack animals and rail transport. However, each division had a motorized group of about 200-300 automobiles and about fifty light armored military vehicles. The Japanese Army Air Force had 520 combat-ready aircraft and another 500 in reserve. The Naval Air Force had 600 aircraft in land- and carrier-based formations. The fleet had four aircraft carriers, one under repair at the start of the war, and two aircraft mother ships.

In a war plan formulated in 1932, the Japanese General Staff formulated several requirement plans for conflict situations in China. Two additional divisions from the mainland were planned for the suppression of localized fighting in northern China. Securing access by sea to Peking was assigned to Garrison Army China, which was stationed at Tianjin with 1,700 troops. To accomplish this task, it was to be reinforced by one division. The war plan for what was perceived as the unlikely event of a serious military confrontation with China included the use of the Manchurian-based Kwantung Army, which was to operate in northern China reinforced by ten divisions from the mainland. Two additional divisions were planned to occupy strategically important points on the coast of central China. The plan was expanded in 1937 to include the objective of occupying the five northernmost provinces of China. The troops to occupy individual points in central China were increased to three divisions and were to capture Shanghai, from where they would move on the Guomindang capital, Nanjing.

History

On July 7, 1937, an incident occurred at Marco Polo Bridge in which Japanese and Chinese soldiers engaged in firefights. Whether this incident was provoked by Japan is disputed. This incident marked the beginning of the Second Japanese-Chinese War. The Japanese expected a quick victory, but the Second Battle for Shanghai lasted an unexpectedly long time and resulted in numerous casualties. About 200,000 Japanese and an unknown number of Chinese soldiers were involved in a fierce house-to-house battle. Casualties were very high on both sides, on the Kuomintang side they were estimated at about one third of the fighting soldiers. Japan was not able to win the battle until mid-November, when the Japanese 10th Army landed in Hangzhou Bay and threatened to encircle the Chinese troops.

On November 5, 1937, the Japanese government made an offer to the Chinese government to settle the incident if China would in the future abide by the three principles formulated by Japanese Foreign Minister Hirota Kōki in 1934. The principles were 1. suppression of all anti-Japanese activities, 2. recognition of Manchukuo and a friendly relationship between Manchukuo, China and Japan, 3. joint struggle against communism. The Kuomintang at first refused to enter into negotiations and did not change this attitude until December 2. By that time, however, the Japanese had already conquered Shanghai and the Chinese troops were in retreat. Therefore, the Japanese government was no longer willing to settle the conflict on the previously mentioned terms, but made much tougher demands, namely the demilitarization of North China and Inner Mongolia, the payment of compensation, and the establishment of political structures to regulate the coexistence of Manchukuo, Japan, and China. These conditions were rejected by the Chinese government.

Around December 8, Japanese troops reached Nanjing, the capital of the Kuomintang. They closed in on the city and dropped leaflets urging the defenders to surrender. The Japanese bombarded Nanjing by day and by night. At 5 p.m. on December 12, the Chinese city commander ordered the troops to withdraw. The retreat was disorderly. The soldiers stripped themselves of their weapons and uniforms. Some of them attacked civilians in order to obtain civilian clothes. The panic also gripped the population, and so soldiers and civilians tried to flee to the Yangtze River. In the process, they were even fired upon by friendly fire. There were hardly any means of transport available at the Yangtze River, so that it was almost impossible to remove the troops. During the panic attempts to board the boats, many people drowned in the cold river.

On December 13, Japanese troops occupied Nanjing. In the ensuing three-week Nanking Massacre, more than 300,000 Chinese civilians and plainclothes soldiers were believed to have been murdered. Chiang Kai-shek had the seat of government temporarily moved to Wuhan on the Yangtze River.

Many Chinese commanders feared an attack by Japanese troops and therefore evacuated their areas. Because Chinese industry and military were underdeveloped and the civil war suppressed unified leadership and development, the Chinese army could not attack Japanese troops in a major field battle. Instead, in the first phase of the war, it attempted to move industry and large bodies of troops so that it could build up forces with which to confront the Japanese troops. Smaller attacks, house-to-house fighting in the cities, and taking advantage of the large territory were used to try to slow the Japanese advance. Starting in 1938, the tactic of magnetic warfare was employed. This was to lure the Japanese troops to certain positions (which were to serve as magnets) where they would be easier to attack or where at least their advance could be slowed down.

In January 1938, after the final failure of negotiations, the Japanese government announced that it would wipe out the Chinese national government. Japan decided to launch an offensive towards Wuhan. To make this offensive possible, the first step was to capture the main railway junctions in the north. In order to be able to capture the city of Xuzhou as an important hub, the Japanese soldiers first tried to capture the Chinese garrison city of Tai'erzhuang. However, the Chinese troops allowed the Japanese to walk into a trap and encircled them in the Battle of Tai'erzhuang. According to Chinese figures, about 30,000 Japanese soldiers fell. This was the first major defeat of the Japanese in the war. Although the city was captured in a second attempt on May 19 and the Battle of Xuzhou also ended victoriously for the Japanese, the myth of Japan's invincibility was broken. The Chinese troops had failed to pursue the remnants of the Japanese forces, otherwise a renewed offensive against the cities might have lasted even longer. The Japanese government mobilized in April 1938 and thus considerably reinforced its troops.

On June 9, 1938, Chiang Kai-shek ordered the dams of the Yellow River to be breached and the country flooded. He hoped that this would slow down the Japanese advance. On June 11, the Yellow River broke its banks between Kaifeng and Zhengzhou and subsequently poured into Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu provinces, seeking its old riverbed. Since the civilian population was not warned, about 890,000 Chinese died, 4,000 villages and 11 cities were destroyed, and about 12 million people were left homeless. This even changed the entire course of the river until the dikes were repaired on May 15, 1947. The floods, however, caused an interruption of the Japanese campaign against Wuhan for months.

On October 25, the Japanese captured Wuhan with heavy losses. Shortly thereafter, they succeeded in capturing Canton without encountering any major resistance. The Japanese general staff had hoped that China would now admit defeat. This idea, however, was far from Chinese strategy. Since the surrender did not occur, Japanese strategists realized that the war would last much longer than planned. The new Chinese capital became the distant Chongqing. However, Chongqing was not under KMT control, but was dominated by gang leaders. The Japanese bombed the city incessantly until the Chinese, with Soviet help, were able to establish reasonably effective air defenses. After that, Soviet and Chinese pilots even flew sporadic counterattacks as far away as Taiwan.

The Japanese had neither the will nor the means to administer China. Therefore, in March 1940, they set up a puppet government under Wang Jingwei in Nanjing to represent Japanese interests. Wang Jingwei had previously been Chiang Kai-shek's vice-general, but had fled Chongqing on December 18, 1938. Given the brutality of the Japanese, the puppet regime was extremely unpopular among the population.

The Communist Party under Mao Zedong had fled from the Kuomintang in the Long March to Yan'an in 1935 and was now building a new base there. In contrast to the usual communist strategy, it also joined forces with the large landowners and the middle class. Mild reforms helped to draw even the rural poor to the side of the Communists. An anti-Japanese university was established where Mao's teachings were taught, but military training was also provided. The Communists waged intense guerrilla warfare, to which the Japanese responded by destroying villages and killing Communist Party members.

In 1938, the Kuomintang had some 600,000 to 700,000 guerrilla fighters. The nationalist guerrilla movement was centrally directed by the army and concentrated mainly in central China. In northern China, troops of the local warlords also took over this role.

The Kuomintang also suffered from extreme corruption at all levels. Among other things, weapons and food were embezzled, which further worsened the already miserable troop morale and equipment.

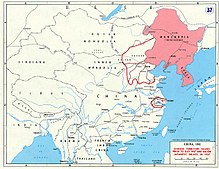

In 1940, the fighting reached a stalemate. Japan occupied the eastern part of China and suffered guerrilla attacks. The rest of China was divided between the Kuomintang, led by Chiang Kai-shek, and Mao Zedong's Communist Party.

In 1941, the united front broke up after repeated fighting between the Kuomintang and the Communists. The Japanese, meanwhile, failed to achieve their goal of cutting off supplies to Chongqing, despite the conquest of Burma and the blocking of the Burma Road to Chongqing. Although a National Chinese counteroffensive in Burma was thwarted, the Allies instead established the Ledo Road to Chongqing from India.

On April 13, 1941, Japan concluded a peace and friendship treaty with the Soviet Union, the Japan-Soviet Neutrality Pact. Japan was more willing to accept a war against the USA and the United Kingdom than to give up the raw material deposits of South Indochina.

The US initially remained neutral. However, after reports of Japanese war crimes such as the NankingMassacre and the Panay Incident, public sentiment shifted. This allowed the U.S. government to impose a steel and oil embargo on Japan and provide military support to the National Chinese faction, including the Flying Tigers. The measures were also taken for geopolitical and economic reasons, as the US did not want to accept Japan's hegemony in East Asia under any circumstances. Their interests in China and the Philippines were directly threatened. Moreover, Japanese domination in East Asia threatened the position there of the European colonial powers of Britain, France and the Netherlands. The embargo made it impossible for the Japanese to continue their actions in China and subsequently led to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

After this attack, China and the USA officially declared war on Japan. This now expanded to the entire Pacific region, as Japan was forced to fight in other theaters of war to secure sources of raw materials.

The Chinese declaration of war did not officially take place until December 8, 1941, because otherwise it would not have been possible for other countries to support China without violating neutrality. The puppet regime installed by the Japanese in Nanjing under Wang Jingwei declared war on the USA and Great Britain in 1943. In 1944, the Japanese once again went on the offensive, creating a fragile land link between their conquests in North and South China.

American General Joseph Stilwell, who had lived in China and therefore spoke Mandarin, was assigned to assist the Kuomintang. He tried to reorganize the National Chinese Army, but ran into problems with Kuomintang commanders, much of whose money and weapons disappeared from the United States. It was not until 1945 that a National Chinese counteroffensive began.

Kuomintang and Communists increasingly gained control of the rural areas, while Japan occupied the cities and the main roads on the east coast.

On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria with over a million troops (see Operation August Storm).

In the summer of 1945, the warring parties assumed that the world war would drag on for at least another year until the USA abruptly ended it by dropping the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945; Japanese troops in China officially surrendered on September 9, 1945 with the signing of the surrender treaty in Nanjing. National Chinese troops had already been sent to Burma and Indochina on August 28 to disarm the Japanese. Vietnam was occupied by Chinese troops north of the 16th parallel until 1946.

See also: Chronology of the Pacific War

Poorly equipped Chinese soldiers repel Japanese attack with over 50,000 troops on Salween River near Burma

Curtiss P-40E of the 75th Fighter Squadron, 23rd Fighter Group at Hengyang, July 1942. The aircraft previously belonged to the 2nd Pursuit Squadron of the Flying Tigers.

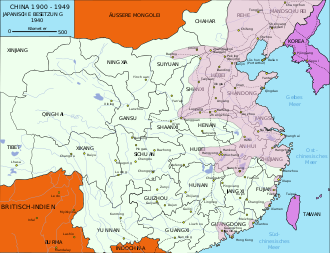

The war situation in 1940: Under Japanese rule in 1930 Former Chinese territory under Japanese rule in 1940

Crying infant after a bombing raid on Shanghai, August 28, 1937.

Japanese reserve on the march along the railway line to Nanjing at Wuxi station before Nanjing, December 1937

Wang Jingwei, Chairman of the Chinese Government established by Japan, together with the German Ambassador Heinrich Georg Stahmer

Course of the war 1937

Three days after the Marco Polo Bridge incident, Chiang Kai-shek announces resistance to Japan

Search within the encyclopedia