Second Battle of El Alamein

Second Battle of El Alamein

Part of: World War II

Major military operations during the African campaign (1940-1943)

1940: Italian invasion of Egypt - Operation Compass1941

: Operation Sunflower - Siege of Tobruk - Operation Battleaxe - Operation Crusader1942: Operation Theseus - First Battle of El Alamein - Battle of Alam Halfa - Second Battle of El Alamein - Operation Torch1943

: Tunisian Campaign

The Second Battle of El Alamein was a decisive World War II battle in the North African theater of war. It took place between 23 October and 4 November 1942 at El-Alamein in Egypt between units of the German-Italian Panzer Army Africa under the command of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and the British 8th Army under Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery. Rommel had previously pushed the 8th Army back east into Egyptian territory to 100 km from Alexandria, but had been unable to break through the British defensive position established there despite several attempts. The goal of Montgomery's long-planned major offensive was the destruction of the German-Italian forces in North Africa. The Allies were able to rely on their material superiority, while the Axis forces, on the other hand, lacked supplies and fuel. The battle ended with an Allied victory and the retreat of the German-Italian troops.

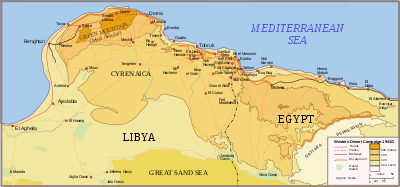

In the following months, the Axis powers had to continue the march back west. Thus, first the Kyrenaika and finally all of Libya were lost. After the American-British landing in Algeria and Morocco in mid-November 1942, a two-front war developed, which ended after the Tunisian campaign with the surrender of the German-Italian troops in May 1943.

The battle was particularly important in the Anglo-American world, as it ended the widespread concern that the Axis powers would break through to the strategically important Suez Canal. The Second Battle of El Alamein is largely responsible for Montgomery's high profile and reputation, partly due to British coverage.

Previous story

Starting in September 1940, Italian units, under direct orders from Benito Mussolini, advanced into Egypt, where they were able to capture the border town of Sidi Barrani. For this reason, the Allies carried out a counter-offensive under the code name Operation Compass, during which they penetrated 800 kilometres into Libyan territory and inflicted heavy losses on the Italian troops. However, as the British units were needed in Greece, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill gave an order to hold. By this time, the Allies had almost succeeded in driving all Italian contingents out of North Africa.

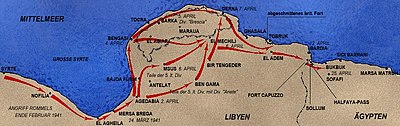

The first German units landed in Italian Libya on 11 February 1941. They were assigned the task of acting as a blocking force to avert a complete loss of the Italian colony to the British. However, the German Afrika Korps under General der Panzertruppe Erwin Rommel went on an independent counterattack and was able to recapture almost all of the lost territory. The advance of the German units in April 1941 was only stopped at the Egyptian border town of Sollum, and the siege of Tobruk, which lasted until November 1941, was ultimately unsuccessful.

In November 1941, the Allies carried out a successful counterattack under the code name Operation Crusader. The Axis forces were subsequently forced to retreat to their initial positions in western Cyrenaika. In the course of a renewed offensive starting in January 1942, the German-Italian units were able to capture Tobruk on 21 June 1942.

The advance ended in the First Battle of El Alamein, some 100 km west of Alexandria. In accordance with Axis plans, a breakthrough of the Alamein position was to be forced on 1 July, but this failed despite initial successes. Therefore, Rommel ordered the temporary cessation of the offensive to allow regrouping with a view to resuming the offensive. Based on this information in combination with ultra intelligence, the Allied formations in turn unsuccessfully took up the supposed pursuit.

By 9 July all regrouping on the south wing had been completed. In the course of the ensuing attack, high priority was given to straightening the frontal advance of the New Zealand 2nd Division. Meanwhile, while the German-Italian attack in the south of the front initially proceeded according to plan, Allied troops launched an offensive that began at 6 a.m. on 9 July. After the Australian 9th Division, together with the 1st Army Tank Brigade, achieved a breakthrough, the Panzer Army had to bring in strong forces to seal off the breakthrough. This led to the cessation of the German-Italian attack, which was resumed unsuccessfully by the 21st Panzer Division on 13 July.

Meanwhile, the results of radio reconnaissance prompted the commander-in-chief of the Allied formations, Claude Auchinleck, to plan a further offensive centred on the centre of the front. Shortly after the attack began on 15 July, Allied forces were able to destroy most of the Italian X. Army Corps, however the 21st Panzer Division together with the two reconnaissance divisions were able to stop the Allied advance. As a result of these and other minor successes, the British Army High Command came to believe that the Italian formations were on the verge of collapse. This resulted in the planning of a new attack by XIII Corps, which failed to achieve its objectives despite strong artillery support.

After the successful German counterattack on 22 July, New Zealand troops launched a renewed attack, in the course of which they were able to break through the Italian lines and advance to Hill 63. A counterattack by 5 Armoured Regiment at Qattara slope stabilised the situation again. Two further major British attacks failed, so that Auchinleck ordered the cessation of offensive operations on 31 July.

With the supply situation continuing to deteriorate and indications of large Allied reinforcements, the Axis forces planned to force the decision before the end of August 1942. The attack date had originally been set around 26 August, but was delayed due to the shortage of operating supplies, which massively slowed the gradual deployment of armoured forces. Albert Kesselring, who at this time held the position of Commander-in-Chief South, gave the final go-ahead to carry out the offensive by assuring the airlift of fuel stored on Crete, thus preventing Rommel from waiting for the arrival of two tankers whose scheduled arrival dates at Tobruk were 28 and 29 August respectively.

At 10 p.m. on August 30, the attack began with the advance of the German-Italian offensive group on the south wing from its initial position between the El-Taqa plateau and the Ruweisat Ridge; a little later, German-Italian units opened the planned entrenchment attacks in the northern and central sections of the front. These initially proceeded largely according to plan, while the motorized units in the south made much slower progress than Rommel's planning had envisaged.

This was due to the sometimes unexpectedly great depth of the minefields and the strong Allied sentries at certain points on the front. In the context of the massive Allied air attacks, in which two German commanders had been killed, and the arduous terrain, the German-Italian units found themselves in a difficult situation. By the morning of the following day, the offensive group was only 4 instead of 40 kilometers east of the British minefields.

After initially ordering the temporary cessation of the offensive, Rommel decided to continue the attack after a situation orientation. According to the new plan, the DAK was ordered to make an advance to Hill 132 of the Alam Halfa Ridge from the northeast in front of the town of Himeimat six hours later, at 12 noon (after a later change, 1 p.m.), with the 15th Panzer Division on the right wing and the 21st Panzer Division on the left wing. The Italian XX. Army Corps (mot.), which had already been stuck at the front mine bar at the beginning due to a failure of the mine detectors, slowly moved up and was ordered to continue the northern attack, which had as its objective the capture of Alem el Bueib-Alam el Halfa, together with the 90th Light Africa Division. To continue the attack, the Commander-in-Chief South mobilized all operational dive bombers.

After initial successes, the German tank contingents got into the deeper sand, which resulted in the consumption of a large amount of fuel. Later, the 15th Panzer Division made an all-out attack on the strategically important Hill 132 beginning at 6:30 p.m., but failed to capture it despite having reached tank bases by 7:50. The 21st Armored Division, meanwhile, was engaged in firefights with Allied troops about four kilometers to the west and was holed up near Deir el Tarfa from 18:30. Meanwhile, the allied units of the Italian XX. Army Corps (mot.) had fallen behind, and the Allied troops had managed to retreat in a northerly and northwesterly direction with few casualties, so strong counterattacks were expected the following day. Furthermore, the strong British-American air attacks continued.

After the temporary cessation of the offensive on the night of 31 August-1 September, the 15th Panzer Division made one last unsuccessful advance on Hill 132, which failed for lack of fuel after repulsing a British counterattack. Later, Rommel was informed of the sinking of the expected tankers by Ultra, leaving the Panzer Army largely exposed to permanent air attacks. In Rommel's estimation, the movement of larger tank formations was largely impracticable, leading him to reflect on an early abandonment of the offensive, which the commander-in-chief ordered to be carried out after superior tank formations were sighted by air reconnaissance beginning on 3 September. Having reached a peak the previous day, the air attacks subsided again from 4 September and, together with the improved fuel situation, made possible an orderly withdrawal to the initial position, following the minefields captured earlier, by 6 September.

.png)

The course of the battle of Alam Halfa

Burning German Panzer IV, British Crusader on the right (27 November 1941 during the British Operation Crusader)

Advance of the Afrika Korps towards Egypt until 25 April 1941

Initial Situation

Situation of the Axis Powers

Strategic Operational Situation

At the end of September 1942, Rommel gave a lecture to Adolf Hitler in which he continued to assess the supply situation in Panzer Army Africa as "extremely critical". Without a solution to this problem, Rommel said, the theater of war in Africa could not be held.

Rommel also reported that the first signs of U.S. material feeds (aircraft, tanks and motor vehicles, closed air force formations) were already visible. Furthermore, he reported that the British Air Force had demonstrated its extraordinary strength, and that British artillery was being used in a mobile and numerous manner with inexhaustible masses of ammunition. Rommel criticized the Italian units under his command, saying that they had "failed again" mainly as a result of structural problems. In the offensive, the Italian units were not usable, in the defensive only with German support.

For a resumption of offensive operations, the Commander-in-Chief of the Panzer Army Africa imposed the following conditions:

- the replenishment of the German associations,

- the improvement of the supply situation,

- the appointment of a "German Plenipotentiary for the entire transport sector Europe-Africa".

Rommel had already made parts of the demands unsuccessfully before the Battle of Alam Halfa. As he was aware, the prospects for resuming the offensive were poor, despite his optimism shown to Benito Mussolini on 24 September. The high level of confidence at the Führer's headquarters made him all the more concerned for it, and through the propaganda of Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, Rommel felt compelled to bolster optimism even further by appearing at major public events and in press conferences. This he regretted in retrospect.

Meanwhile, Rommel's ailing condition, having already suffered from stomach trouble before the Battle of Alam Halfa, had not improved appreciably, so that in early September he yielded to his doctor's urgent advice and showed himself ready for an extended stay in Europe. On his way to his home in Wiener Neustadt, where Rommel had been commander of a war school before the outbreak of war, he lectured Cavallero, Mussolini, and Hitler. He left the theatre of war with mixed feelings, however, as Rommel assumed that Winston Churchill would launch a major offensive in Egypt in the space of the next four to six weeks. Rommel saw an offensive in the Caucasus as the only way to stop this. Other key leaders were temporarily absent through wound or illness, including Alfred Gause, Chief of the General Staff of the Panzer Army and both his IC and Ia, Friedrich Wilhelm von Mellenthin and Siegfried Westphal. Furthermore, all division commanders had changed during the last ten days, as had the Commanding General of the Afrika Korps, Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma had taken over from Major General Gustav von Vaerst. The replacement of the Army Commander-in-Chief by General der Panzertruppe Georg Stumme also proved to be problematic. Although Stumme was an experienced commander of armoured units, he had not yet fought on African soil, had a heart condition and, as a man convicted by a court martial, was under parole from Hitler. Stumme was killed in action in June 1942 under dramatic circumstances as commander of the XXXX. Panzer Corps shortly before the start of the summer offensive, albeit through no direct fault of his own. Meanwhile, the absent Erwin Rommel in Wiener Neustadt was always informed about the current situation and was ready to return to the front immediately at the start of the British offensive.

Considerations of the different management levels

Hitler, who had promised, among other things, the transfer of a Nebelwerfer brigade with 500 tubes as well as 40 Panzerkampfwagen VI Tigers and assault guns, some with sieve ferries, similarly to the Italian Chief of the Army General Staff Ugo Cavallero with his promises of fuel, did not keep his promises. Only Mussolini had made no promises and already appeared resigned. In his view, the war in the Mediterranean was "lost for the time being." Italy no longer had "sufficient shipping space", and next year one had to "reckon with a US landing in North Africa". In Rommel's opinion, a faked attack in October 1942 and, under the condition of a favorable supply situation, "the decisive attack", which would be very difficult, was possible in the middle of winter [...]. Mussolini finally agreed with this view.

In retrospect, Rommel suspected that the Duce had not grasped the seriousness of the situation. The latter considered Rommel a physically and morally broken man, which is why he also calculated on the replacement of the commander-in-chief of the Panzer Army. In the end, despite Rommel's efforts, nothing changed for the better; the tonnage discharged had been falling since July 1942, dropping again in August after another minor peak in July, rising again in September, and dropping again in October.

Supply tray

|

|

From the beginning of the fighting in the African theater of war, both sides were confronted with the problem that the desert offered no resources to supply the troops. This was especially significant for the Axis powers, since they, unlike the British, had no supply base on the African continent and thus the entire supply situation depended on sea transport from Italy. Furthermore, the increasing distance between the ports and the actual front proved to be problematic as the German-Italian success grew. To illustrate the distances involved, the Israeli historian Martin van Creveld gives the example that the distance between Tripoli and Alexandria was about 1930 km, which is roughly twice the distance between Brest-Litovsk on the German-Soviet demarcation line and Moscow. Added to this was the fact that only a few railway sections existed, so that most of the way had to be covered by trunk roads, of which the Via Balbia, which was vulnerable to both weather and air attacks, was the only one in Libya.

The lack of experience in the desert war also led to the wrong diet for the soldiers, whose rations contained too much fat. This in turn was partly responsible for the general perception that a deployment in Libya lasting longer than two years could result in permanent health damage for the individual concerned. Furthermore, the wear and tear on engines increased due to overheating, which was particularly noticeable in the motorcycles used. But also the tank engines were massively affected, so that their life span was reduced from about 2250-2600 km to about 480-1450 km. Already at the time of the German landing in North Africa, when the front had stabilized due to the withdrawal of British units to Greece near Sirte, Mussolini pointed out to the German Plenipotentiary General at the headquarters of the Italian Wehrmacht, Enno von Rintelen, that the supply lines to Tripoli, at about 480 km, were 1 ½ times as long as they could normally be effectively managed due to the lack of a railway connection.

Over the entire period of fighting in the North African theater of war, the disproportionately high demand for motor vehicles to maintain a stable supply situation also proved highly problematic. Creveld states that the Afrika Korps received ten times as much in motorized transport capacity relative to the forces made available for the planned Unternehmen Barbarossa.

Another significant problem was the lack of port capacity, which in the meantime led to the Tunisian port of Bizerta being used for unloading cargo from Italy after negotiations with the Vichy government. By the summer of 1941, however, not a single Axis ship had entered Bizerta. The reasons Creveld gives for this are that the French were alarmed after the British occupation of Syria and that the German authorities also had their reasons, though he does not elaborate on them. Even the recapture of the port of Bengasi, which was closer to the front, did not solve the problem at all, since instead of the theoretically possible 2700 tons a day, a maximum of 700-800 tons of cargo could be unloaded. The reason for this was that Benghazi was within Royal Air Force range and therefore frequently attacked. Creveld also doubts that the capture of the port of Tobruk as late as 1941, which offered a theoretical capacity of 1500 tons per day, but which was only partially utilized in practice with a maximum of 600 tons of cargo unloaded daily, would have solved the problem of the lack of capacity.

Beginning in early June 1941, when the X. Fliegerkorps, which had previously protected the convoys, was transferred to Greece, the loss rate among the German-Italian convoys increased massively, and the British bases on Malta, among others, were able to recover. The situation did not ease until the start of Rommel's second offensive in January 1942, when absolute losses of shipping fell by 18,908 GRT despite an increase of 17,934 tons in the total cargo shipped to Libya. After dropping steadily from January to April, losses increased in May and June, only to multiply in August after a drop in July.

At the beginning of September, the bread ration had to be halved due to a shortage of flour, and the coveted additional rations had to be cancelled completely. In addition to flour, the army also lacked fat. During this time, the number of sick in the individual units continued to rise permanently, which was partly due to malnutrition. Furthermore, the available amount of fuel did not allow any major movements of the motorized troops, and the ammunition stock also remained scarce.

After Georg Stumme had taken over the command of the army due to Rommel's absence - he had taken a cure on the advice of his doctor - he demanded a complete reorganization of the supply in the sense of Rommel, but in a personal letter containing his demands he also partly showed himself already resigned and hoped for Rommel's return soon. At the start of the major British offensive, the Commander-in-Chief South, Albert Kesselring, as well as Panzerarmee Afrika itself, considered the operational supply situation to be serious and therefore ordered air transport. On the same day, the Luftwaffe flew 100 tons of fuel from Maleme on Crete to Tobruk.

In October, rations and ammunition stocks improved slightly. However, 30% of the army's motor vehicles were undergoing repairs at the time, and the supply of water also proved problematic due to various storms. As a result, on 23 October, the day the attack was to begin, the High Command of the Panzer Army was forced to state "that the army, in the present fuel situation, does not have the operational freedom of movement that is indispensably necessary".

The high losses, which had increased rapidly since June 1942, also proved to be problematic for the Panzer Army. In the Battle of Alam Halfa alone, the Panzer Army Africa had lost numerous tanks and other vehicles and 2910 soldiers in eight days. By bringing in mainly infantry (the bulk of the 164th Infantry Division was flown in from Crete, albeit with only a few heavy weapons), the German High Command attempted to achieve a refreshment of the weakened forces in Egypt.

Defense Preparedness

Immediately after the retreat of the offensive group on the south wing at the Battle of Alam Halfa, the High Command of Panzer Army Africa ordered the construction of a new defensive line, which was to run along the lines of the newly captured British minefields. The new defensive front consisted of two lines. In the first line were the Italian troops, the second line was formed by the Afrika Korps, which acted as an intervention reserve.

The northern section (coast to Deir Umm Khawabir) was defended, as before, by the Italian XXI Army Corps, consisting of the Bologna and Trento Infantry Divisions, together with the German 164th Light Africa Division. In the central section (up to Deir el Munassib), the Italian X. Army Corps with the Brescia Infantry Division and the Trieste Motorized Division, and the 90th Light Africa Division together with the Ramcke Hunter Brigade. South of it, in the section up to Qaret el Himeimat, were the Italian XX. Army Corps (mot.), consisting of the two weakened armored divisions Ariete and Littorio with the Folgore paratrooper division and the German reconnaissance group.

The Afrika Korps was placed with the bulk of its forces behind the Italian XX. Army Corps, with two battle groups being detached behind the Italian XXI Army Corps. By 18 September, the Italian XX. Army Corps was also held back as a reserve, which meant that the two Italian infantry corps had to occupy the positions alone. The division was that the XXI Army Corps, together with half of Ramcke's Brigade, secured the north as before, while the X Army Corps, with reinforcements from the Italian Army Corps, secured the north as before. Army Corps, with reinforcements from the Folgore Division paratroopers and Ramcke Brigade, had to guard the position in the area from Deir Umm Khawabir to Qaret el Himeimat. The southern flank of the corps was secured by a reinforced reconnaissance division. Behind the northern part of the northern section, the Littorio Armored Division was stationed together with the 15th Armored Division as an intervention reserve; to the north of the southern section, the Ariete Armored Division and the 21st Armored Division were each deployed in three joint battle groups in such a way that the mass of divisional artillery could fire barrages in front of the main battle line (HKL) of the XXI and X Army Corps. Armeekorps could fire. The distribution of German Army artillery was in several groups across the entire width of the front.

Due to a failed commando raid against the supply nodes of Tobruk, Bengasi and Barce on 13 and 14 September 1942, special attention was paid to flank protection. The Siwa oasis was covered by the Italian Young Fascist Division together with one Italian as well as one German reconnaissance division each. The mission of the 90th Light Africa Division was to protect the area around El Daba on the coast together with Sonderverband 288. In addition to this, the Italian Pavia Division with another German reconnaissance division was available in the Marsa Matruh area, which it was to defend against possible landings as well as attempted northern bypasses by the British Army.

In its defensive preparations, the Panzer Army applied the so-called "corset bar principle", which had already been practiced successfully before the Battle of Alam Halfa. The "corset bar principle" was the insertion of German battalions between the Italian infantry battalions and was practiced in particular at front sections with critical situations. However, the units were not integrated into each other, but continued to be subordinated to the national command authorities. In order to improve cooperation, the command posts were placed very close to each other and the same orders were given, whereby the German General Staff occasionally gave suggestions for the deployment of the Italian troops, since their leadership was considered to be "not decisive".

At the end of September, the High Command of Panzer Army Africa ordered a depth-staggered dispersal due to the losses in the war of position so far. The forward mine barriers were guarded at a depth of 500 to 1000 meters only by outpost strips. Behind this followed an empty space of up to two kilometers, behind which lay the new main battle line in the rear half of the minefields. To defend the new HKL, Rommel ordered the reinforcement of the rear minefields, for which, due to a shortage of mines, various explosives such as aerial bombs were used. These minefields were called "devil's gardens". In depth, the main battlefield adjoining the HKL covered about two kilometers; a battalion was assigned a section about 1.5 kilometers wide and five kilometers deep.

All possible defensive measures were carried out, which led to the fact that almost the entire planned deep division of the Panzer Army Africa was already completed on 20 October. Only the mining of the coastal section was not yet completed. In the course of this work 264,358 mines had been laid by German and Italian sappers since 5 July 1942, resulting in a total of 445,358 mines including the earlier Allied minefields.

Enemy Reconnaissance

Beginning with the beginning of October, the signs of an imminent large-scale offensive by the British 8th Army under Bernard Montgomery became stronger. Stumme, like Rommel, was of the opinion that the best solution was to advance with an offensive of his own, which he also wrote in his letter to Ugo Cavallero on October 3. However, the commander-in-chief of Panzer Army Africa added that the supply in the near future was not sufficient for this and that a counterattack from the defensive was more possible. This should have the destruction of the 8th Army and subsequently the capture of Alexandria as its goal.

In the High Command of Panzer Army Africa, the exact British offensive intention was viewed in a differentiated manner: An offensive was expected to extend across the entire front. The center of gravity could lie, as mentioned by the reconnaissance group, between Himeimat and Deir el Munassib in the south of the front, but stronger troop contingents were expected along the coastal road. From the middle of the month onwards the start of the attack was expected almost daily, the 8th Army having been considered already fully replenished. The Panzer Army was thus surprised not in terms of the timing of the attack, but in terms of the focus of the British attack.

As possible places of a breakthrough attempt were mentioned in a daily order of the Panzer Army Africa of 15 October:

- on both sides of Deir el Munassib and to the south (on 23 October only diversionary attacks took place there)

- on both sides of el Ruweisat (there were no British attacks there)

- on and south of the coast road (this section was assigned to Australian units).

German reconnaissance did not recognize the main thrust of the offensive from 23 October in the west and northwest of the city of El Alamein. In this section to the north of the Alamein front was only the 15th Panzer Division and not the 21st Panzer Division, which had been left in the south because of the main direction of attack expected there. Since German air reconnaissance could not sight the British center of gravity because of its problems, which were close to a total failure, the two armored divisions, which constituted the main striking force of the Panzer Army, were too far apart to implement with immediate effect the operational defense concept developed on 15 October. This envisaged encircling the enemy troops that had broken through "with the motorized forces tied in the front in a pincer-like counterattack" and then immediately destroying them.

The High Command of Panzer Army Africa was not swayed by the view of the Chief of the Foreign Armies West Division in the Army General Staff, Colonel i. G. Liß, who had visited the Army troops on 20 October and did not believe in the major offensive even after the attack had begun. Liß saw in the portents of a U.S.-British landing in Northwest Africa merely signs of the offensive in Egypt, which he expected to begin in early November.

By October 28, the Panzer Army had largely identified the enemy breakdown:

| Structure of the 8th Army according to the findings of German enemy reconnaissance | |||

| British 8th Army (Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery) | |||

| X Corps | |||

| 1st Armoured Division | |||

| 10th Armoured Division | |||

| XIII Corps | |||

| 50th (Northumbrian) Division | |||

| 44th (Home Counties) Division | |||

| 7th Armoured Division | |||

| 5th Indian Infantry Division | |||

| XXX Corps | |||

| Australian 9th Division | |||

| 51st (Highland) Division | |||

| New Zealand 2nd Division | |||

| South African 1st Division | |||

Allied situation

Allied attack preparations

The commander of the British 8th Army, Bernard Montgomery, with the support of the British Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, Harold Alexander, was able to calmly carry out the complete rebuilding of the army and complete it before the start of the offensive. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill pushed several times for an earlier date to begin the attack, but the two planners were not swayed by this. In response to Churchill's demand that the offensive begin as early as September, Montgomery and Alexander announced that they had set the date for the start of the attack for the end of October. At this the British Premier finally resigned, replying, "We are in your hands."

After the victory at the Battle of Alam Halfa, Montgomery's prestige soared. He made major changes in commanders, ranging from generals to division commanders down to colonels, appointed the veteran Herbert Lumsden, who had previously commanded the 1st Armored Division, to command the X Corps, which had been elevated to elite status. Army Corps, he also directed the army's training himself. Montgomery relieved himself of details of army command by appointing a Chief of the Army General Staff on the German model. This individual was charged with the task of coordinating the work of the staff, a position such as this being rather unusual in Britain. The newly created post was held by Brigadier Freddie de Guingand. With his personality, he was also able to compensate for Montgomery's inability to deal with other people in this position.

After the restructuring of the army, three different types of divisions were available:

- the armoured (armoured -),

- the motorized (light, mixed),

- the infantry divisions.

By 11 September, 318 Shermans and self-propelled guns had arrived in Africa, personnel were rehearsed, and the USAAF already had its own commands and staffs, but they depended on the cooperation of the British command. The offensive was planned down to the last detail. Claude Auchinleck, Montgomery's predecessor, had already ordered the preparation of an offensive in July 1942 that was to have its center of gravity in the north. The reason for the selection of the northern section was that in this part of the front the Allied material superiority could be better exploited than in the south. The importance of this consideration was again reinforced by the intensive and extensive defensive preparations of Panzer Army Africa in the southern section before the British offensive began in October. Immediately upon his arrival, the new Commander-in-Chief of the British 8th Army, within a week of his arrival in Egypt alone, drew up the complete offensive plan, which he submitted on 14 September to the 13 Commanding Generals and Division Commanders and to the staff in the Army High Command for the elaboration of further details.

Allied planning

According to Montgomery, this concept, code-named Operation Lightfoot, was aimed at destroying the forces facing the Eighth Army. According to the plans, the tank army tied up in its positions was to be destroyed. In the event that, contrary to expectations, German or Italian troops broke out to the west, the plan was to pursue them and deal with them later. The attack was to be launched in the moonlight of 23 October 1942 by the simultaneous beginning of the advance of the XXX. Corps in the north and the XIII Corps in the southern section, although it was intended to bring about the decision in the north. The task of the XXX. (Infantry) Corps was to advance into the German-Italian minefields with very strong artillery support, either drive back or destroy the Axis troops, and then clear the mines. The space thus newly gained was to be given to the X. (Panzer) Corps as a bridgehead for the further advance westward, "to exploit the success and complete the victory."

For the following morning this X. Corps, which constituted Montgomery's main thrust, was ordered to cross the "Devil's Garden" divided into two corridors at first light with the 1st and 10th Armored Divisions, then to hold out behind it and finally, in a pincer attack, to take rearward territory of Panzer Army Africa, which blocked the Kattara track (Telegraph or Ariete track of the Panzer Army) extending from north to south. The runway represented the most important route of the army's local supply, as this runway, which ran behind the main battle line, connected the position front with the coastal road.

The advance of the XIII Corps on the south wing, consisting of one armored and two infantry divisions, served mainly to distract and tie down the German-Italian forces. Furthermore, however, limited objectives were created for the corps. During the advance, Qaret el Himeimat was to be brought back under British control, and in the event of a favorable situation, the 4th Armored Brigade was to advance to El Daba so that the supply depots and airfields there could be taken from the Axis forces. Montgomery's plan ended with the summarized principles which he constantly impressed upon one of his troops without signs of fatigue: if the offensive succeeded, it would bring about the end of the war in the North African theater of war, in addition to purges; indeed, "It will be the turning point of the whole war." In his view, the will to win and the morale of the 8th Army were also of great importance, for "no tip and run tactics in this battle, it will be a killing match; the German is a good soldier and the only way to beat him is to kill him in battle."

Montgomery, however, was forced to change his plans on 6 October. The date for the start of the attack was already fixed at 23 October 1942 and the commander-in-chief of the British 8th Army also knew that the outcome of Operation Torch, the Allied landing in French North Africa, as well as the behaviour of the French based there and the extent of the US commitment in the Mediterranean area depended on the outcome of this offensive.

The background to the change in the British plan of attack was an analysis by the Intelligence Division on the Army Staff that the system of defences of the Armoured Army of Africa was going to be more complicated than originally thought. In addition to this problem, the degree of the present state of training of the army was also found to be unsatisfactory, and the commanders of the armoured units were opposed to the previous plan. In particular, the Commanding General of the new elite corps, the X. Corps, Lumsden, to whom Montgomery had assigned the decisive role, predicted problems for the breakout of his corps' tanks from the minefield to the west. He complained about the role of his unit, which was to operate merely in support of the infantry. According to the new concept of attack, the XXX. Corps and the X. Corps were now to begin their advance at the same time, so that both tanks could support the infantry and vice versa.

However, this still did not solve the problem of concentrating the two corps in one combat section. Montgomery dispelled Lumsden's concerns by issuing an order that the tanks should take up a position within the German-Italian minefields to cover the fight against the enemy infantry. For this reason the two German panzer divisions, which constituted the main thrust of Panzerarmee Afrika, would then have been compelled to attack against the X. Corps, which would have failed, as at the Battle of Alam Halfa, against a great steel wall of superior tanks and tank guns. By the start of the decisive battle in North Africa on the moonlit night of October 23-24, the German-Italian forces were heavily outnumbered in every respect-both in materiel and personnel-by the 8th Army.

Balance of power

Four days before the start of the attack, the Panzer Army reported the inventory of 273 operational German main battle tanks as well as 289 Italian main battle tanks, which meant an increase of 39 German models and a loss of 34 Italian tanks compared to the level of five days before. Among these 273 German tanks, however, only 123 were modern models. Among them were 88 Panzerkampfwagen III with the long 5-cm KwK, seven Panzerkampfwagen IV with short 7.5-cm KwK, and 28 with long 7.5-cm KwK. The Italian models had little combat value compared to the British and US tank types. In contrast, the British 8th Army was able to muster a superior number of 1,029 operational tanks on the day of the attack, which could still be reinforced by 200 vehicles held in reserve and 1,000 under repair and conversion. Among the tanks ready for action, almost half were American tank types, consisting of 170 Grants as well as 252 Shermans, whose frontal armor could be penetrated exclusively by the 8.8-cm FlaKs. On 23 October, these contingents were opposed by 250 German tanks.

The situation with the air forces was similar. Despite many tactical sorties by the German and Italian air forces in September and October, it could not be prevented that the British Royal Air Force increasingly gained air supremacy even over the rear area of the Panzer Army. The two attacks of the X. Fliegerkorps at the end of September on the British supply base in the Nile Delta with eight and five aircraft, respectively, could only change little. Altogether, the German Luftflotte 2 with 914 aircraft (528 operational) for the entire Mediterranean area faced 96 operational Allied squadrons with over 1500 aircraft operating in the Middle East under the command of Air Marshal Arthur Tedder.

Previously, in October, the Axis air forces had once again undertaken a major attack against Malta with enormous effort, but it failed because of British air defenses. The British night attacks with Wellington bombers against the Italian convoys therefore continued unchanged.

In terms of artillery, too, the material superiority of the Commonwealth troops over the German-Italian units was similar to that already enjoyed by the air forces and the Panzerwaffe. In the run-up to the battle, the Allied troops were able to muster over 900 field artillery pieces and medium artillery pieces. In addition to this, the Commonwealth forces had 554 2-pounder as well as 849 6-pounder anti-tank guns at their disposal. Panzerarmee Afrika used a variety of different anti-tank weapons, of which the 7.5-cm PaK 40 and the 5-cm PaK 38 were the most effective. Available on the eve of battle were 68 pieces of the PaK 40 and 290 pieces of the PaK 38. In addition to these, as of 1 October 1942, the Panzerarmee could muster 86 8.8-cm FlaKs, but only a portion of these were used for anti-tank purposes.

A total of about 152,000 Axis soldiers were on Egyptian soil three days before the start of the battle on October 23. This contingent consisted of 90,000 German and 62,000 Italian troops. Of these, 48,854 German soldiers and 54,000 Italian soldiers were under the command of Panzerarmee Afrika. If these figures are reduced to the actual combat strength known only of the German troops, the strength of the German contingents consisting of the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions, the 90th and 164th Light Africa Divisions, the higher artillery commander Africa, and the two tactically subordinate major units of the Luftwaffe consisting of the 19th Flak Division and the Luftwaffe Fighter Brigade 1, totaled 28,104 men, reinforced by 4,370 men in alert units from the staffs and supply troops. The total combat strength of the German units was therefore 32,474 soldiers. Assuming a similar strength of the Italian contingents of two armored divisions plus one motorized, one infantry, and one fighter division, the approximate total combat strength of the Panzer Army was about 60,000 men.

Equating the term "fighting strength" used by Ian Stanley Ord Playfair with the German word Gefechtsstärke, the German-Italian troops would be confronted with formations of 195,000 British, Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Indians, Poles and Free French, which would mean a more than threefold superiority of the Allied contingents. In air power, quite apart from the difference between the navies, the superiority was probably even greater.

Participating units of the Axis powers and the Allies

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overview of the battlefield in Libya/Egypt

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Second Battle of El Alamein?

A: The Second Battle of El Alamein was a major battle in the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War that took place from 23 October to 5 November 1942.

Q: What was the significance of the First Battle of El Alamein?

A: The First Battle of El Alamein had stopped the Axis from attacking deep into Egypt further.

Q: Who took command of the British Eighth Army in August 1942?

A: Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery took command of the British Eighth Army in August 1942.

Q: What was the outcome of the Second Battle of El Alamein?

A: The Allied victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein turned the tide in the North African Campaign and ended Axis's hopes of occupying Egypt, taking control of the Suez Canal, and reaching the Middle Eastern oil fields.

Q: Who was forced to retreat to the former French fortifications in the Mareth Line after the Second Battle of El Alamein?

A: Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Corps were forced to retreat back to the former French fortifications in the Mareth Line in the border between Tunisia and Libya.

Q: When did the Second Battle of El Alamein take place?

A: The Second Battle of El Alamein took place from 23 October to 5 November 1942.

Q: Who led the Allied forces to victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein?

A: Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery led the Allied forces to victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein.

Search within the encyclopedia