Sacco and Vanzetti

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For the feature film, see Sacco and Vanzetti (film).

Ferdinando "Nicola" Sacco (b. April 22, 1891 in Torremaggiore, Province of Foggia, Italy; † August 23, 1927 in Charlestown, Massachusetts) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (b. June 11, 1888 in Villafalletto, Province of Cuneo, Italy; † August 23, 1927 in Charlestown, Massachusetts) were two workers who immigrated to the United States from Italy and joined the anarchist labor movement.

They were accused of participating in a double robbery-murder and found guilty in a controversial trial in 1921. After several rejected appeals by the legal profession, the death sentence followed in 1927 after seven years in prison. On the night of August 22-23, 1927, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair at Charlestown State Prison.

Both the guilty verdict and the final sentence on April 9, 1927, resulted in mass demonstrations worldwide. Critics accused the US justice system of a politically motivated judicial murder based on questionable circumstantial evidence. Exculpatory evidence had been insufficiently appreciated or even suppressed. Hundreds of thousands of people participated in petitions seeking a stay or suspension of the execution of the sentence.

In 1977, Massachusetts Democratic Governor Michael Dukakis released a statement saying that the trial of the duo had been "riddled with prejudice against foreigners and hostility to unorthodox political views" and therefore not fair.

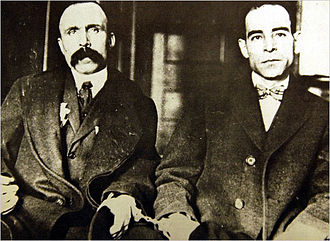

Vanzetti (left) and Sacco (right) as defendants, handcuffed to each other

Backgrounds

Biographical background

Nicola Sacco

Ferdinando "Nicola" Sacco was born on April 22, 1891 in Torremaggiore in the south of Italy. He was the third of seventeen children. His father sold olive oil and wine from his own production. Christened Ferdinando, he changed his first name to Nicola after a brother with that name died. Nevertheless, his baptismal name continued to be used by him and his friends.

Whether he attended school as a child is not certain. In any case, he helped his father early in the cultivation of the fields. Agriculture, however, did not interest him. When his older brother Sabino was invited to Massachusetts, USA, by a friend of his father, Nicola gladly came along. When he was barely seventeen years old, he reached America on April 12, 1908. He made his way as a water carrier for a construction company and a worker in a foundry. When, after about a year, Sabino returned home, Nicola remained in the United States at his own request. At the Milford Shoe Company he trained as a skilled laborer in 1910, and as a clerk was now earning a little more money than before. In 1912 he married Rosa Zambelli, then seventeen years old, usually called Rosina by Sacco. Their son Dante was born in 1913. Sacco was described by friends and relatives as a loving father and family man. At the time of his arrest, his wife was five months pregnant with daughter Ines.

The young Sacco was already inspired in Italy by his brother Sabino for socialist ideas. In the States, he and his wife became involved in a group of Italian anarchists. In 1916 he was arrested and fined for speaking at an unauthorized anarchist meeting. Fearing that he would be drafted for military service, he fled to Mexico with other anarchists for a few months in 1917. Among them was Vanzetti, whom he had met about a week earlier. After returning, Sacco worked for various companies and shoe factories as a roustabout. At the 3-K Shoe Company, its owner Michael F. Kelley, who had formerly been a department manager at the Milford Shoe Company, remembered Sacco's dependability and diligence. Sacco was hired there in November 1918 and earned up to eighty dollars a week through piecework, which was an above-average worker's salary. In addition, he took care of the boiler and heating of the company building during the winter of 1918/19, for which he visited the factory every night. He is therefore often erroneously described as the company's night watchman.

Bartolomeo Vanzetti

Bartolomeo Vanzetti was born on 11 June 1888 in Villafalletto near Cuneo. His mother already had a son from a previous marriage. After the death of her husband, she married Giovanni Vanzetti. Bartolomeo was the first of four children of the Vanzettis. Bartolomeo attended school for at least three years, the exact length of which is not reliably recorded. He is described as a curious and inquisitive child. However, his father Giovanni, who ran a farm as well as a coffee house in Villafalletto, determined for his son the profession of a confectioner. At the age of 13 Bartolomeo left the parental home to start his apprenticeship. During the strenuous training period in various Italian cities, he was repeatedly plagued by illness. At the age of 19, now in Turin, he was brought home because of a severe pleurisy. He never resumed work as a confectioner. Instead, he first worked in his family's garden. The year he returned home, his mother died of liver cancer, which was very upsetting to Vanzetti. Against the wishes of his domineering father, Vanzetti left home in 1908, just before his 20th birthday, to emigrate to the United States.

There he kept his head above water with odd jobs, moving from town to town before settling in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1913. He lost his job with the Plymouth Cordage Company after actively participating in a strike. In the fall of 1919, he went into business for himself as a fish salesman. Vanzetti lived in Plymouth with the Italian anarchist Vincenzo Brini as a lodger. He had neither married nor had children himself, but he built up an intimate relationship with the Brini family and their three children. After fleeing to Mexico and returning to Plymouth in 1917, the Brini family could no longer take him in due to lack of space, and he lived with the Fortini family until his arrest.

Shaped by his painful experiences as an unemployed man in his early years in the States, his doubts about religion grew, and he turned increasingly to anarchist ideals. In his autobiography he wrote:

"In America I experienced all the sufferings, disappointments and privations which are inevitably the lot of one who arrives here at the age of twenty, knowing nothing of life and having something of a dreamer in him. Here I saw all the cruelty of life, all the injustice and corruption with which humanity so tragically grapples. [...] I sought my freedom in the freedom of all, my happiness in the happiness of all."

Joint activities

Sacco and Vanzetti had emigrated from Italy to America in 1908, but first met in May 1917, by which time they had joined the anarchist movement around Luigi Galleani. Galleani himself was arrested and deported in 1919 because of the rigid policy against foreign radicals.

Shortly before Sacco and Vanzetti met, the United States had entered World War I with the declaration of war on Germany in April 1917. The pair fled to Mexico with the intention of evading muster and the threat of military service in the war, which was essentially fought on European battlefields. In fact, under the law, aliens whose naturalization proceedings had not yet been completed could not actually be required to serve in the war. Three or four months later they returned, but used false names for some time, since they faced a prison sentence because of their flight from registration.

The letters they both wrote to each other during their imprisonment for the South Braintree robbery-most of the time they were housed in separate cells and jails-suggest more of a companionable relationship than a warmly friendly one.

Historical-political background

With the end of the First World War in November 1918, the USA fell into an economic depression. The number of unemployed increased sharply, prices rose continuously. In addition to strikes, an increased crime rate was the result of the disastrous economic situation. In addition, the successful communist revolution in Russia frightened the political leadership of the United States that was in power at the time. In September 1919, after splitting from the Socialist Party, the Communist Party and the Communist Labor Party were founded. In addition, there were various groups of anarchists and others from the spectrum of the revolutionary left, each with different ideological orientations. Government propaganda now blamed the political left across the board for the bad state of the country, calling them indiscriminately criminal "Bolsheviks" who would do anything to bring about a communist revolution in the United States. The stoked "Red Scare" was fed by a large number of bombings attributed to anarchists. For example, on June 2, 1919, eight bombs exploded in various cities across the country. These were accompanied by leaflets with threats from "anarchist fighters" against the "capitalist class".

The fear of "Bolsheviks" went hand in hand with the fear of immigrants. The latter, according to propaganda, made up ninety percent of all radicals in the country. Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer, whose house was damaged in one of the attacks, then ordered brutal raids on institutions and organizations of and for foreigners beginning in November 1919. The general public welcomed these so-called Palmer Raids, which were aimed at tracking down "individuals inclined to radicalism" and expelling them from the country. Citing the imminent danger to the country, these raids disregarded existing laws or changed them to the detriment of the immigrants in question. In addition, witnesses and reporters reported serious assaults on the - mostly blameless - detainees.

The trail of anarchist pamphlets led investigating agents to a Brooklyn print shop. Two of the employees were arrested in February 1920. One of them, typesetter Andrea Salsedo, fell from the 14th floor of a New York police building on the morning of May 3. He had been held and interrogated without warrant for two months by then. Rumors of torture were making the rounds in anarchist organizations. The circumstances of the fatal fall were never fully clarified. This incident caused great consternation and fear of further raids among anarchist groups.

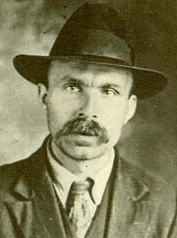

Nicola Sacco

Bartolomeo Vanzetti

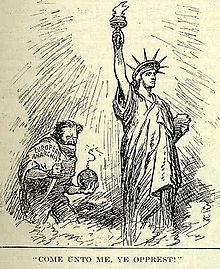

Publicistic expression of the Red Scare: The propaganda cartoon in the Memphis daily newspaper Commercial Appeal (1919) depicts the clichéd image of a European anarchist as a criminal who wants to destroy the Statue of Liberty. This is ironically accompanied by the biblical quotation (Mt 11:28 EU ): "Come unto me, ye oppress!" ("Come unto me, ye oppressed").

Before the trial

The robberies

On the morning of December 24, 1919, an armored car robbery occurred in Bridgewater. The robbery failed, the armed gangsters fled without loot.

About four months later, on April 15, 1920, two men armed with handguns shot and killed Frederick Parmenter, a payroll clerk, and Alessandro Berardelli, a security guard, two employees of the Slater & Morrill Shoe Company, in SouthBraintree, Massachusetts. The perpetrators took $15,776.51 (2021 value approximately $201,000) in payroll money that the victims were carrying. They fled in a dark blue Buick with two to three other men inside. That this double robbery-murder was connected to the Bridgewater robbery was never proven beyond a reasonable doubt. However, the investigating authorities assumed that it was. After his arrest as a suspect in the South Braintree case, Vanzetti also had to stand trial for the attempted robbery in Bridgewater.

Investigation and arrest

Initial police suspicions that the so-called Morelli gang might be behind the South Braintree robbery were quickly dropped by Bridgewater Police Chief Michael E. Stewart. He suspected anarchists were behind the robbery. He apparently relied on the following circumstantial evidence: a radical named Ferruccio Coacci, who was to be deported for distributing anarchist writings, had failed to report on April 15 as agreed with the authorities. From this, Stewart concluded that Coacci might have been one of the perpetrators at South Braintree. In addition, Stewart believed the South Braintree robbery-murders were connected to the attempted armored car robbery in Bridgewater four months earlier. According to an unconfirmed witness statement, the latter was to have been carried out by a group of anarchists.

Stewart had the house searched that Coacci, who had been deported in the meantime, had occupied. In the shed he thought he had discovered tire tracks of a Buick and thus of the getaway car. Mike Boda (also: Mario Buda), who also belonged to an anarchist organization, still lived in the house. He stated that his Overland car was normally stored in the shed, but that it was currently being repaired in a garage. After the police visit, Boda went into hiding. Stewart then instructed the owner of the garage to call him as soon as Boda was due to collect his car.

On the evening of May 5, 1920, Boda came to the workshop with three other men from his anarchist organization. Among them were Sacco and Vanzetti. The owner's wife informed the police by telephone. Whether Boda and the others noticed this is not certain. What is certain is that the men left early and without the car: Boda and one of the companions on a motorcycle, in which they had also come, Sacco and Vanzetti on foot. After about a mile, the two boarded a streetcar bound for Brockton. The Brockton police, meanwhile, were notified by Stewart. While still on the streetcar, Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested as "suspicious persons." When arrested, both were carrying weapons: Sacco a .32 Colt, Vanzetti a .38 Harrington & Richardson revolver and several shells for a shotgun.

At the Brockton police station, Sacco and Vanzetti were interrogated separately, first by Stewart, then a day later by Norfolk County District Attorney Frederick G. Katzmann. In the process, they were not told the reason for the arrest. They were not questioned about the robbery-murders themselves, or only indirectly; the interrogations focused on their political attitudes. Both lied about acquiring the weapons and denied being anarchists or adhering to other leftist ideologies. They also claimed to know neither Boda nor Coacci.

True, the others who came to pick up the car were also suspects. But there was no match for the witness statements and the conspicuously short Mike Boda. The other companion had a clear alibi. Nor was any evidence or circumstantial evidence found against Sacco and Vanzetti that would have linked them compellingly to any of the robberies. A comparison of fingerprints on the recovered getaway car failed to produce a match. The suspicion that the looted money would have gone to anarchist organisations could also not be confirmed by an investigation. The negative result and the investigation itself, however, were not admitted by the Justice Department until August 22, 1927, the day before the execution. Katzmann, like Stewart, nevertheless maintained that both robberies had been carried out by a particular group of anarchists and that Sacco and Vanzetti had been involved.

Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee

In the wake of the arrest and charges against Sacco and Vanzetti, which appeared ideologically motivated, the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee was formed under the leadership of Aldino Felicani, an anarchist experienced with propaganda. This committee publicized the case, raised money, and appointed defense lawyers. The extent to which the committee's activities benefited or harmed Sacco and Vanzetti remains a matter of debate, even when considering the case as a whole.

Bridgewater: indictment and sentence against Vanzetti

Through testimony of the factory manager and his fellow workers, Sacco had a valid alibi for December 24, 1919, the day of the Bridgewater robbery. Thus, only Vanzetti was indicted on June 11, 1920, for attempted robbery and murder in Bridgewater. The trial began in Plymouth on June 22, 1920, with Judge Webster Thayer presiding.

The prosecution, led by Katzmann, essentially relied on three witnesses who, in the course of the preliminary investigation and the trial, sharpened their statements, in some cases significantly, to Vanzetti's disadvantage. Vanzetti's alibi was corroborated by fourteen Italians who testified that Vanzetti had sold them and others eels for Christmas Eve on the morning of December 24. Concerned by his attorneys that his political views might turn the jury against him, Vanzetti refrained from testifying on his own.

Judge Thayer instructed the jury that the Italian nationality of the defense witnesses should not be construed to their disadvantage: "No inference unfavorable to them should be drawn from the fact that (the defendant's) witnesses are Italian." On July 1, 1920, Vanzetti was found guilty by a jury of intent to rob and murder. He was sentenced by Judge Webster Thayer on August 16 to a term of twelve to fifteen years, to be served in Charlestown Prison until execution.

Search within the encyclopedia