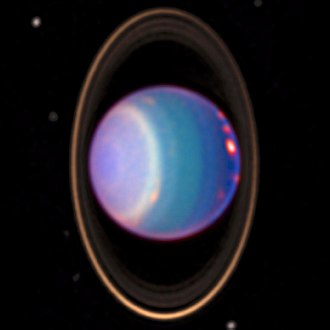

Rings of Uranus

The planet Uranus is surrounded by a system of planetary rings, which in its variation and complexity does not come close to the much larger orbits of Saturn's rings, but can nevertheless be classified before the simpler structures of Jupiter's and Neptune's rings. The first rings of Uranus were discovered on March 10, 1977, by James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Douglas J. Mink. Although astronomer Wilhelm Herschel had reported observing rings 200 years earlier, today's astronomers doubt that it was possible to actually perceive the ring system given their dark and pale appearance with the means of the time. Two more rings were discovered in 1986 in images taken of the planet by the Voyager 2 spacecraft, and an additional pair of rings was found between 2003 and 2005 in photos taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Since then, 13 independent rings of the ring system of Uranus are known. Ordered by distance from the planet, they are designated 1986U2R/ζ, 6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ, ε, ν, and μ. Their radii are 38,000 km for the 1986U2R/ζ ring and reach 98,000 km for the μ ring. Additional dull dust bands and incomplete arcs could be observed between the main rings. The rings are extremely dark, so the spherical albedo of the ring particles does not exceed 2 per cent. They are probably composed of frozen water that has combined with some dark, radiation-absorbing organic components.

Most of the Uranus rings are opaque and only a few kilometers wide. The ring system consists of small objects, the majority of which are between 0.2 and 20 m in diameter. Some of the rings are optically very small: for example, the extended and dull 1986U2R/ζ, μ, and ν rings are composed of thin dust particles, while the narrow and also dull λ ring is composed of larger objects. The relative absence of dust within the ring system is explained by the drag imposed by Uranus' extended exosphere through its corona.

It is assumed that the rings of Uranus are not older than 600 million years and thus relatively young. The ring system probably consists of the remains of a large number of moons that originally orbited the planet before colliding with each other a long time ago. After collisions, the moons broke apart into countless pieces, which then survived as the narrow and optically dense rings visible today and now surround the planet in strictly defined orbits.

The process of how the narrow rings are held in their shape is still not fully understood. Initially, it was assumed that each narrow ring was associated with a pair of nearby so-called shepherd moons that supported their shape. However, during its 1986 flyby, Voyager 2 was only able to detect a pair of shepherds (Cordelia and Ophelia) that exert an influence on the brightest ring (ε).

Uranus with its rings (Hubble Space Telescope, 1998)

Schematic of the Uranus ring-moon system. The solid lines indicate rings; dashed lines represent the orbits of the moons.

Discovery

The first mention of a ring system surrounding Uranus dates from the 18th century and is found in the notes of Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel, in which he wrote down the findings from his observations of the planet. These contained the following passage:

"February 22, 1789: A ring was suspected." (translated: "February 22, 1789: A ring was suspected.")

Herschel drew a narrow diagram of the ring and further noted that it "tended a little towards the red". The Keck telescope in Hawaii was able to confirm this, at least with respect to the ν-ring. Herschel's notes were published in the Royal Society Journal in 1797. Over the years, serious doubts were raised as to whether Herschel could have seen anything of the sort at all, while hundreds of other astronomers had been unable to make out anything of the sort. Nevertheless, there are legitimate objections that Herschel could indeed give a precise description of the dimensions of the ν-ring in relation to Uranus, its changes as Uranus moved around the Sun, and its color appearance. In the following two centuries between 1797 and 1977, Uranus' rings were rarely, if ever, mentioned in scientific papers.

The undisputed discovery of the rings of Uranus can finally be attributed to astronomers James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Douglas J. Mink on March 10, 1977, who succeeded in sighting the rings with the help of the Kuiper Airborne Observatory. However, this event only came about as a result of a chance observation. Originally, they planned to study the atmosphere of Uranus by observing the occultation (occultation) of the star SAO 158687 by the planet. When they analyzed their observations, they discovered that the star was shown to have briefly disappeared five times each before and after the planet's passage. They concluded that a system of narrow rings must exist around the planet. The five occultations they observed they marked in their papers with the Greek letters α, β, γ, δ, and ε They ultimately retained this designation as a label for the rings to this day. Later they traced four more rings; one between the β and γ rings and three within the α-ring. The first one they called η-ring, the latter ones, according to the numbering of the occultation events, received the designation ring 4, 5 and 6. After Saturn's rings, it was thus the second ring system that had been discovered within our solar system.

When the Voyager 2 spacecraft passed through the Uranus system in 1986, the first image documents showing the rings in plan view were produced. Two more dull rings were discovered, bringing the total number of rings to eleven. Then, between 2003 and 2005, the Hubble Space Telescope was able to detect another pair of rings that were not previously visible, bringing the total number of rings known today to 13. The discovery of these outer rings also doubled the known radius of the ring system. Hubble's images also revealed two small satellites, one of which, the moon Mab, shares its orbit with the newly discovered outermost ring.

Animation of an occultation of the star SAO 158687 by UranusClick on the image to start

The Kuiper Airborne Observatory in flight

Basic properties

As already mentioned, the ring system of Uranus consists of 13 clearly definable rings according to the present state of knowledge. Ordered according to their distance from the planet, they are called 1986U2R/ζ, 6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ, ε, ν and μ. They can be divided into three groups:

- the nine main narrow rings (6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, ε),

- the two dust rings (1986U2R/ζ, λ)

- and the two outer rings (μ, ν).

The rings of Uranus consist mainly of macroscopic particles with some dust added. Thus, dust has been detected in the 1986U2R/ζ-, η-, δ-, λ-, ν- and in the μ-ring. In addition to these known rings, numerous optically thin dust bands and other dull rings may well exist between them. However, such dull rings and dust bands may exist only temporarily or may be composed of a number of separate arcs, which can sometimes be made out in occultation observations. Some of them were visible, for example, in 2007 during a special astronomical event in which the ring surfaces crossed each other several times as seen from Earth. A number of dust bands could also be made out between the rings in photos taken by Voyager 2 during a geometric forward scatter. All the rings of Uranus continued to show some variations in brightness when observed at an azimuthal angle.

The rings each consist of extremely dark substances. The geometric albedo of the ring particles never exceeds a value of 5 to 6 percent, while the spherical albedo is even lower, at about 2 percent. At a phase angle between the lines sun-object and observation position-object of nearly zero, a clear increase of the albedo of the ring particles can be seen, whose value increases significantly here. This means that, conversely, their albedo is much lower when they are observed even slightly outside the opposition region. The rings appear slightly red in the ultraviolet and visible parts of the spectrum and grey in the near-infrared region. They do not exhibit any discernible specific spectral characteristics. The chemical composition of the ring particles is still unknown. However, it is certain that they cannot be made of pure ice like the rings of Saturn, as they are too dark for this and appear even darker than the inner moons of Uranus. This suggests that they may be composed of a mixture of ice and dark components. While the nature of these components is unclear, they could be organic compounds that are significantly darkened by charged particles emitted by Uranus' magnetosphere. It is likely that the ring particles consist of highly processed chunks, which initially show similarities to the nature of the inner moons.

On the whole, the ring system of Uranus is neither comparable to the dull dusty rings of Jupiter nor to the broad and complex ring structure of Saturn, where some ring bands consist of very bright material and chunks of ice. Nevertheless, there is certainly similarity to some parts of the latter ring system. For example, Saturn's ε-ring as well as its F-ring are both narrow, relatively dark, and each is guarded by a pair of moons. The newly discovered outer rings of Uranus, in turn, possess features consistent with the outer G and E rings of Saturn. Thus, narrow rings are found in Saturn's wide rings just as they are in Uranus' narrow rings. In addition, dust bands between the main rings could be observed, as they also occur in the rings of Jupiter. This contrasts with the ring system of Neptune, which is similar to that of Uranus, but less complex, definitely darker and more dusty. In addition, Neptune's rings are positioned much further from their planet.

The inner rings of Uranus: The bright outer ring is the Epsilon ring, beside it 8 other rings are visible. (Voyager 2, 1986, distance 2.52 million km)

Search within the encyclopedia