Revolutions of 1848

Revolutions of 1848/1849 include revolutionary uprisings in various European territories that were an expression of the delayed modernization of society, the economy, and the system of rule. This revolutionary movement was part of a pan-European process of change against the Metternich system. Through it, the economic, social and political changes that had begun with the Industrial Revolution in England and the French Revolution of 1789 were developed further. The revolutionary movement of 1848/1849 was a significant turning point in European history.

In many regions of Europe, social, economic and political tensions had built up, which erupted violently from the beginning of 1848. On the one hand, the revolutionary movement affected regions such as France, the states of the German Confederation and Northern Italy that were already in the transition to industrialisation, but on the other hand, it also affected regions such as Southern Italy and large parts of the Habsburg Monarchy that were still purely agrarian in structure. The striving for national self-determination can be seen as a common overarching element of these revolutions.

In addition to France, the states of the German Confederation and the Italian peninsula, tripartite Poland and Hungary, which was striving for independence, are considered to be significant centres of the "European Revolution" of 1848/1849. In Eastern Europe, the uprisings spread as far as Transylvania and the Danubian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. In individual regions, the events escalated into interstate wars or assumed civil war-like proportions.

Contemporaries saw the revolutions in Europe as having failed in the autumn of 1849. For more than a century, many historians saw it that way as well. Today, the long-term effects and the immediate successes are viewed much more positively. In many European countries, peasant liberation and agrarian reforms were completed, the constitutional principle was enforced, basic individual rights were largely secured, and a parliamentarization of the political order was initiated, although in this area in particular many resistances and counterweights remained for a long time. The formation of the nation-state, violently suppressed in 1849 in the Italian and German principalities, led there in the medium term to a kind of reversal of the revolution. Various German historians interpret the development that followed the revolution as a "revolution from above". It led to the founding of the Kingdom of Italy on the Italian peninsula in 1861 and, between 1866 and 1871, to the founding of a German nation-state, the German Empire, under Prussian domination.

May Day Uprising in Dresden, 1849

Popular festival in Rome at the proclamation of the Roman Republic, February 1849

Proclamation of the revolutionary Wallachian constitution (Proclamation of Islaz) on 27 June 1848 in Bucharest

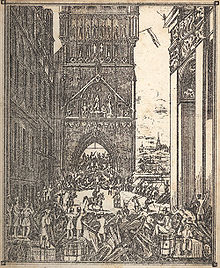

Whitsun Uprising in Prague, mid-June 1848: barricade fights at the bridge tower of the "Prague Bridge" (renamed Charles Bridge in 1870)

Barricades built by the revolutionaries in Vienna, May 1848

Proclamation of the Repubblica di San Marco on 23 March 1848 in Venice

Barricades during the Five Days of Milan in March 1848

February Revolution 1848 in Paris

March Revolution 1848 in Berlin

Centres of the revolutionary uprisings of 1848/1849 in Europe

Factors and structural similarities of the European revolutions

According to the historian Wolfram Siemann, there are several common features that were decisive, in varying degrees, for the European countries and regions. First, the uprisings of the "grassroots revolution" were mostly carried by those strata that were most affected by hunger, unemployment and lack of social prospects in the countryside and in the cities. Then, in the constitutional bodies newly created by the uprisings, the liberals' struggle to enshrine civil rights in state constitutions began.

The socio-economic crisis

The socio-economic crisis of pre-industrial, artisanal professions, based on the pre-March overpopulation of entire regions, favoured the incipient proletarianisation of the large cities as well as large parts of the rural areas. The old class order finally collapsed. Pauperism, the onset of industrialization, the market orientation of professions and classes, and the prolonged crisis of the crafts are terms that characterize the profound changes of the two pre-revolutionary decades. This crisis manifested itself in Luddism, persecutions of Jews, or demands for guild protection of the crafts from the competition of capital. The movement of 1848 - together with the peasant revolt often referred to as the basic revolution - was ambivalent in nature: it expressed itself both as a defensive crisis against the direct manifestations of early industrialization and as a struggle for emancipation of the politically uninfluential strata of the population.

Hunger crises

A second common feature is the crop failures and subsequent famine and dearth crises of 1845 and 1846, culminating in 1847. This was the last great famine in the industrialized countries of Europe, with tumults and a hugely increased wave of emigration in the second half of the 1840s. The worst pre-revolutionary hardship was in Ireland, but famines in German regions - not least Silesia - also had a great public resonance.

International economic crisis

An international economic crisis overlaid the preceding hunger crisis and led to a wave of strikes in German cities in April 1848. Many data confirm a profound process that already led Friedrich Engels in retrospect to the judgement that the world trade crisis of 1847 had been the real mother of the February and March revolutions (→ British railway crisis).

Struggle for law and constitution

A fourth European dimension lies in the systemic affinity of constitutional demands. Everywhere, internal political struggles developed into disputes over a new order based on a written constitutional document. It was about law and constitution - about civil rights and constitution. This was already the case in the July Revolution of 1830, but it happened even more strongly in the run-up to the Revolution of 1848, which received its initial impulse not from France but from Switzerland and Italy. The issue was always the revision or enactment of a constitution: example: At the center of the so-called "March Demands" circulating in Germany were constitutional demands: Fundamental rights, especially freedom of the press and assembly, jury courts, people's armament - in very different senses - and elections to a national parliament.

The crisis of the international system of 1815

Another European dimension lies in the character of traditional international politics, based on international treaties and relations. It was immediately clear to contemporary politicians, above all Metternich, who was still serving as foreign minister and state chancellor, that in the spring of 1848 the international system founded at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 was at stake. This was a matter of politics between European states, and the German Confederation, which had been created in 1815 as a subject of international law, counted as one of them. In 1848 it was called into question; finally it transferred all powers to the revolutionary Provisional Central Authority in Frankfurt. The initiative for this had come from the Frankfurt National Assembly. Its real purpose was to draft an imperial constitution for the whole of Germany. With its first great act the National Assembly reached far beyond this by establishing a national government. This was a revolutionary act. On June 28, 1848, the National Assembly established an imperial government consisting of an imperial administrator, a prime minister, and imperial ministers of foreign affairs, domestic affairs, finance, justice, commerce, and war. In the overall assessment, researchers today agree that the revolution and also the work of unification did not fail because of a fundamental resistance of the European powers to German unity. The revolution of 1848/49 came up against the edge of a possible great European war, which could have unleashed the breakthrough of the principle of nationality and anticipated a later development in the 19th century. The European powers, led by England and Russia, worked against this.

The politics of European persecution and exile

A repressive variant of this international policy was the concerted action of the counter-revolution. Here Austria, Russia, and from 1850 onwards France and Belgium also participated in police cooperation. This policy of European persecution - and the suppression of the European revolution - created a sixth dimension that corresponded to its European character: European exile. Switzerland and Alsace served as temporary protection, London developed into the central transit point, and the United States of America was the actual place of escape.

The European character of nationalism

A seventh dimension is related to the European character of nationalism. For many nationalities, the myth of the "unredeemed" nation was formed in the first half of the nineteenth century; this included first and foremost the Greeks, Italians, Hungarians, Poles, but also the Czechs and, according to the wording of some oppositional propaganda, the Germans. The roots of this nationalism lay in the French Revolution of 1789, which was the model for national symbols, colours and flags. In the Vormärz, under the system of the Restoration, the further myth of the "springtime of peoples" developed. In the 1820s it expressed itself throughout Europe in the movement of philhellenism, the enthusiasm for the Greek struggle for freedom, and in the 1830s, after the failed Warsaw Uprising of November 1830, in the common European wave of Polish friendship. This pre-March utopia collapsed in the face of the possibility, now suddenly visible in 1848, of transforming nationality into the state-nation. Hans Rothfels once aptly described the nationalities of the 19th century as "a kind of nation aspirants": as ethnic minorities striving for more independence and still seeking their political unity. "From the unity of the nation to the discord of nationalities" - this is the formula one could use to describe the dilemma that developed.

The Frankfurt National Assembly succeeded in finding an answer to the nationality question at home. The nationalism of 1848/49, based on the constitutional state, offered the protection of national minorities by respecting their native languages and religiosity. The Imperial Constitution of 1849 had assured this as a fundamental right in its Clause 188. A similar balance was achieved in the draft submitted by the Constitutional Committee of the Vienna Imperial Diet for the multi-ethnic state of the Habsburg Monarchy. Neither of these constitutions came into being in this form, but they did point the way to peaceful coexistence of different nationalities in a united state.

The pacifist internationalism

A last - eighth - European dimension has only recently been properly perceived. It is the "pacifist internationalism" (Dieter Langewiesche). In September 1848 a first international peace congress took place in Brussels, in August 1849 they met in Paris and a year later in the Paulskirche. The congresses called on the states to disarm, to abolish standing armies, to renounce interventions and not to finance wars of third powers.

Caricature by Ferdinand Schröder on the defeat of the revolutions in Europe, published in the Düsseldorfer Monatshefte under the title "Rundgemälde von Europa im August 1849".

Conditions, contents and objectives

Even before this, there had been liberalizing tendencies in some principalities (for example, as early as 1846 in the Papal States and subsequently in other Italian states in the form of the introduction of constitutions with civil rights) or revolutionary developments, such as the Sonderbundskrieg of November 1847 between the Catholic-conservative and liberal cantons in Switzerland, which resulted in the transformation of the Confederation from a confederation of states to a federal state with the unified constitution of September 1848; - Developments that influenced the uprisings in France and the states of the German Confederation (cf. March Revolution) from February/March 1848 onwards. These processes, sometimes referred to as the Spring of Nations, continued in part into 1849. They were essentially uprisings directed against the restoration policy of the most powerful Central European principalities and monarchies of the so-called Holy Alliance, which had been adopted after the Congress of Vienna of 1814/15. Since the end of the wars of the coalition, the restoration powers - led by the monarchs of Austria, Prussia, Russia and (to a limited extent) France, who were oriented towards eighteenth-century absolutism and the idea of the divine right - had endeavoured to restore the power and social structures in Europe that had prevailed before the French Revolution of 1789 (cf. Ancien Régime).

The uprisings against the Restoration were carried by the ideas of classical liberalism, which were based on the Enlightenment and combined with the idea of the nation state (nationalism), which was considered progressive at the time, and the principle of popular sovereignty. In this respect, many of the revolutions of 1848/49 were also the result of national unity and independence movements, each developed in different ways, which had already developed in the preceding decades - often in the political underground (see also Vormärz and Democratic Movement (Germany)). Demands were made for constitutions for the respective state entities, freedom of the press, freedom of opinion and other democratic rights, popular armament and the establishment of citizen militias, peasant liberation, liberalisation of the economy, the abolition of customs barriers, and even the abolition of monarchical ruling structures in favour of the establishment of republican state entities, or at least the restriction of the power of princes in the form of constitutional monarchies.

On the socio-economic level, the socio-structural side-effects of the Industrial Revolution, which began in Great Britain in the mid to late 18th century with new technical developments in production and trade and spread to continental Europe in the course of the 19th century, formed an important breeding ground for the surveys. Due to a strong population growth during the early industrialization in the first half of the 19th century, with simultaneously stagnating productivity growth and a crisis-like development in the crafts (especially the textile trade) and in agriculture, intensified by bad harvests and in their consequence famines (famine winter 1846/47, cf. also the so-called "potato revolution" of April 1847 in Berlin), discontent with the prevailing social conditions also grew among the increasingly needy population of landless peasants and the newly emerging stratum of the industrial proletariat. Against this background, a new revolutionary base developed, on which early socialist ideas already had an impact (cf. also Pauperism, the pre-industrial mass poverty, and Social Question).

The revolutions, which were initially weakened in some (e.g. Italian and German) countries by concessions made by the ruling princes in the form of constitutional pledges and the introduction of liberal reforms, are considered to have failed, especially with regard to the imagined area of Germany and Austria - at least with regard to their immediate suppression there until late summer 1849. Many activists emigrated or emigrated permanently thereafter from their countries of origin, often overseas. In the United States in particular, the new immigrants of this period were singled out as Forty-Eighters over other immigrants of earlier or later times.

Search within the encyclopedia