German revolutions of 1848–1849

![]()

Märzrevolution is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see March Revolution (disambiguation).

The German Revolution of 1848/49 - also known as the March Revolution in reference to the first phase of the revolution in 1848 - was the revolutionary event that took place in the German Confederation between March 1848 and July 1849. The uprisings also affected provinces and countries outside the federal territory that were under the rule of the most powerful federal states of Austria and Prussia, such as Hungary, Upper Italy or Posen.

The related events were part of the liberal, bourgeois-democratic and national unity and independence uprisings against the restoration efforts of the ruling houses allied in the Holy Alliance in large parts of Central Europe (cf. European Revolutions 1848/1849). As early as January 1848, Italian revolutionaries had risen against the rule of the Austrian Habsburgs in the north of the Apennine Peninsula and the Spanish Bourbons in the south. After the French February Revolution began, the German lands also became part of these uprisings against the Restoration powers that had ruled since 1815 after the end of the Napoleonic Wars (see also democratic movement in Germany).

In the German principalities, the revolution began in the Grand Duchy of Baden and within a few weeks spread to the other states of the federation. From Berlin to Vienna, it forced the appointment of liberal governments in the individual states (the so-called March Cabinets) and the holding of elections to a constituent National Assembly, which convened on May 18, 1848, in the Paulskirche in the then free city of Frankfurt am Main. After the successes achieved relatively quickly with the March riots, such as the abolition of press censorship and the liberation of the peasants, the revolutionary movement was increasingly put on the defensive from the middle of 1848. Even the peaks of the uprisings, which flared up again especially in the autumn of 1848 and during the imperial constitutional campaign in May 1849, and which regionally (for example in Saxony, the Bavarian Palatinate, the Prussian Rhine Province and especially in the Grand Duchy of Baden) assumed civil war-like proportions, could no longer stop the ultimate failure of the revolution with regard to its essential core demand. By July 1849, the first attempt to create a democratically constituted, unified German nation-state had been put down with military force by predominantly Prussian and Austrian troops.

The persecution of supporters of liberal, republican-democratic or socialist views that accompanied the suppression of the revolution and the subsequent era of reaction caused tens of thousands to flee the German states in the years after 1848/49. They initially found asylum mainly in France, England or Switzerland. Many who could afford a sea voyage lasting several weeks sought for themselves and their families the personal and political freedoms denied them in their original homeland overseas. In Australia and the United States, the term Forty-Eighters exists to describe immigrants who fled the German lands between the late 1840s and the mid-1850s.

Cheering revolutionaries after barricade fights on 18 March 1848 in Breite Straße in Berlin

Historical classification

Stakeholders

The revolutionaries in the German states sought political freedoms in the sense of democratic reforms and the national unification of the principalities of the German Confederation. Above all, they advocated the ideas of liberalism. In the further course of the revolution and afterwards, however, liberalism increasingly split into different directions, which set different priorities in essential areas and partly opposed each other (among other things, in their attitude to the status of the nation, the social question, economic development, civil rights, as well as to the revolution itself).

Circles with radical democratic, social revolutionary, early socialist and even anarchist aims were also heavily involved in the revolutionary activities and uprisings on the ground. Their activities were mainly extra-parliamentary; in the parliaments they were underrepresented or not represented at all. They were therefore unable to assert themselves in the decisive bodies of the revolution.

Outside the German Confederation, countries and regions that were affiliated to the Habsburg Empire of Austria sought independence from its domination. These included Hungary, Galicia and the upper Italian principalities. In addition, the revolutionaries in the province of Posen, which was predominantly inhabited by Poles, campaigned for independence from Prussian rule.

Of the five powerful European states, the European pentarchy, only England and Russia remained untouched by the events, in the case of Russia apart from the participation of Russian military in the suppression of the Hungarian independence uprising against the Austrian Empire in 1849. In addition, Spain, the Netherlands and the young and in any case comparatively liberal Belgium remained largely uninvolved in the events of the revolution.

Significance for Central Europe

In most states, the revolution was put down in 1849 at the latest. In France, the republic lasted until 1851/1852. Only in the kingdoms of Denmark and Sardinia-Piedmont did revolutionary successes last longer. There, for example, the enforced constitutional changes into constitutional monarchies lasted into the 20th century. The constitution of Sardinia-Piedmont became the basis for the Kingdom of Italy enforced in 1861 (cf. Risorgimento).

One lasting result of the bourgeois-democratic aspirations in Central Europe since the 1830s was the transformation of Switzerland from a loose and politically very heterogeneous confederation of states into a liberal federal state. The new federal constitution of 1848, made possible by the Sonderbund War of 1847, determines its basic state and social structures to this day.

Although the March Revolution, with its fundamental aims of change, failed to achieve its nation-state objectives and led to a period of political reaction, in historical terms it was the wealthy bourgeoisie that asserted itself and finally became a politically and economically influential power factor alongside the aristocracy. From 1848 at the latest, the bourgeoisie, in the narrower sense the upper middle classes, became the economically dominant class in the societies of Central Europe. This rise had begun with the political and social struggles since the French Revolution of 1789 (cf. also bourgeois revolution).

The revolutions of 1848/49 had a long-term and lasting impact on the political culture and pluralistic understanding of democracy in most states of Central Europe in the modern era: in the Federal Republic of Germany (whose Basic Law is based on the draft constitution drawn up in 1848/49 in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt), in Austria, France, Italy, Hungary, Poland, Denmark and Czechoslovakia (today the Czech Republic and Slovakia). The events of 1848/49 set in motion the triumphal march of bourgeois democracy, which in the long term determined the subsequent historical, political and social development of almost the whole of Europe.

In addition to previous developments rooted in the Enlightenment, the March Revolution provided some ideal impulses for the development of the European Union (EU) in the late 20th century. Even before the revolutionary turmoil of 1848, the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini advocated a Europe of the peoples. He opposed this utopia to the Europe of authoritarian principalities and thus anticipated a basic political and social idea of the EU. Mazzini's corresponding ideas had already been taken up in 1834 by some idealistic republican-minded Germans, among them Carl Theodor Barth, in the secret society Junges Deutschland. Together with Mazzini's Young Italy and the Young Poland, founded by Polish emigrants, they formed the supranational secret society Young Europe in Bern, Switzerland, also in 1834. Their ideals often influenced the mood of optimism at the beginning of the March Revolution, when in many places the revolutionary base spoke of an "international springtime of peoples".

Political map of the German Confederation (1815 to 1866) with 39 founding states

Caricature by Ferdinand Schröder on the defeat of the revolutions in Europe in 1849 and the forced emigration of the Forty-Eighters. First published in the Düsseldorfer Monathefte under the title Rundgemälde von Europa in August 1849.

History

Introduction

A major triggering factor for the March Revolutions was the success of the February Revolution of 1848 in France, from where the revolutionary spark quickly spread to the neighbouring German states. The events in France, where it was possible to depose the bourgeois king Louis Philippe, who in the meantime had increasingly abandoned liberalism, and finally to proclaim the Second Republic, set revolutionary upheavals in motion, the turmoil of which kept the continent in suspense for a year and a half.

The most important centres of the revolution after France were Baden, Prussia, Austria, Upper Italy, Hungary, Bavaria and Saxony. But other states and principalities also saw uprisings and popular assemblies at which revolutionary demands were articulated. Starting with the Mannheim People's Assembly on February 27, 1848, at which the "March Demands" were first formulated, the core demands of the revolution in Germany were: "1. popular armament with free election of officers, 2. unconditional freedom of the press, 3. jury courts on the model of England, 4. immediate establishment of a German parliament."

In the Kingdom of Denmark, revolutionary events led to a new constitution in 1849, introducing constitutional monarchy and a bicameral parliament with universal suffrage.

In some states of the German Confederation, for example in the kingdoms of Württemberg and Hanover, or in Hesse-Darmstadt, the princes quickly gave in. There, liberal "March Ministries" were soon established, which partly met the demands of the revolutionaries, for example by establishing jury courts, abolishing press censorship and liberating the peasants. Often, however, these remained mere promises. In these countries, the revolution took a reasonably peaceful course because of the early concessions.

As early as May/June 1848, the restorative activities of the ruling dynasties began to intensify, increasingly putting the insurgents in the states of the German Confederation on the defensive. In the course of the French February Revolution, the suppression of the Parisian June Uprising was a decisive event for the onset of counterrevolution ("reaction") in the other European states as well. The June Uprising of the Parisian workers is also historically considered to mark the split between the revolutionary proletariat and the bourgeoisie.

A chronological course of the revolution in its entirety is difficult to grasp, since the events cannot always be clearly related to one another, decisions were made at different levels and in different places, sometimes almost simultaneously, sometimes at different times, and then revised again.

Timetable

Pre-revolutionary development

- 18 September 1814 to 9 June 1815: Congress of Vienna. The agreed "reordering" of Europe ushers in the politics of the Restoration. This marks the beginning of the political "Vormärz" phase.

- 18 October 1817: German unity is demanded at the Wartburg Festival.

- Late summer-autumn 1819: In most states of the German Confederation, the Hep-Hep riots lead to anti-Jewish riots directed against the emancipation of the Jews, which in some places escalate into pogroms.

- September 20, 1819: Following the murder of the poet August von Kotzebue, the Carlsbad Resolutions create the legal basis for repressions against democratic and national aspirations of the fraternities and other oppositional circles, e.g. by banning democratic groups and associations, censoring the press, and so on.

- July 1830: The July Revolution in France also triggers some regionally limited uprisings in the states of the German Confederation, such as the Tailors' Revolution in Berlin.

- May 27, 1832: At the Hambach Festival, demands for a united Germany and democratic rights are once again raised.

- April 3, 1833: The attempt at an all-German revolutionary uprising fails during the Frankfurt storming of the guards.

- 1834: In Bern, the secret societies Young Italy, Young Germany and Young Poland, formed by exiled democrats, unite on the initiative of the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini to form the supranational secret society Young Europe.

- 1834: Georg Büchner and Friedrich Ludwig Weidig spread the social revolutionary pamphlet Der Hessische Landbote from the underground in the Grand Duchy of Hesse with the motto "Peace to the huts, war to the palaces!

- 1837: The protest proclamation of the Göttingen Seven (a group of renowned liberal university professors, including the Brothers Grimm) against the abolition of the constitution in the Kingdom of Hanover, spreads throughout the German Confederation. The scholars are dismissed and some of them expelled from the country.

- June 1844: In a region of Silesia, the weavers rise up as a result of increasing social hardship (Weavers' Revolt).

- April 1847: The so-called Berlin Potato Uprising due to increased food prices caused by crop failures in the previous year is put down by Prussian military forces after only a few days.

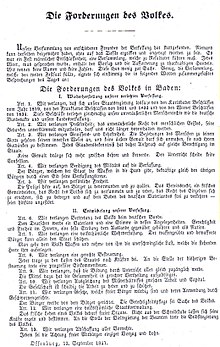

- September 12, 1847: At the Offenburg Assembly, radical democratic Baden politicians demand basic rights with the "demands of the people" and oppose early socialist ideas to the perceived threat of industrialization.

- 10 October 1847: The political programme of the moderate liberals is formulated at the Heppenheim meeting.

Transitional phase to the March Revolution as of January 1848

- January 1848: National revolutionary uprisings against the rule of the Spanish Bourbons in southern Italy (Sicily) and against that of the Austrians in northern Italy (Milan, Padua and Brescia) initiate the pan-European phase of the revolutions of 1848/49.

- February 24, 1848: Start of the February Revolution of 1848 in France. Proclamation of the Second Republic. Prime Minister François Guizot resigns. Citizen King Louis Philippe abdicates and goes into exile in England.

Revolutionary development 1848

- 27 February 1848: Inspired by the February Revolution in France, the Mannheim People's Assembly formulates a petition to the government in Karlsruhe with so-called March demands, thus becoming the beacon of the March Revolution in the states of the German Confederation.

- February 29: The Bundestag establishes a political committee of Bundestag envoys; over the next few weeks, the Bundestag issues several federal resolutions aimed at calming popular unrest.

- March 1: Start of the March Revolution in Baden with the occupation of the House of Estates of the Baden Parliament in Karlsruhe.

- 4 March: Start of the March Revolution in Bavaria with riots in Munich

- March 5: The Heidelberg Assembly invites to the Pre-Parliament.

- 6 March: Start of the March Revolution in Prussia with first riots in Berlin

- March 9: King Wilhelm I of Württemberg, under pressure from the opposition, appoints the opposition leader Friedrich Römer as head of government instead of the conservative Joseph von Linden, and several liberals to the government, appointing them as March ministers.

- March 13: Start of the March Revolution in Vienna with the storming of the Ständehaus; resignation of the State Chancellor Prince Metternich, who emigrates to England.

- 15 March: Under the impression of 20,000 demonstrators, the Governor's Advisory Council in Pest (today Budapest), the highest administrative body of the Hungarian part of the Austrian Empire, approves the demands of radical Hungarian intellectuals around Sándor Petőfi formulated in "Twelve Points" (among others, a ministry independent of Vienna, withdrawal of all Austrian troops from Hungary, establishment of a Hungarian national army and creation of a national bank). The Hungarian government thus effectively turns the Kingdom of Hungary into an independent state. The demands include a ministry independent of Vienna and an independent Hungarian parliament, the withdrawal of all Austrian troops from Hungary, the establishment of a Hungarian national army, and the creation of a national bank.

- 17 March: Milan declares the secession of Lombardy from Austria and its annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont.

- March 18: During the reading of a patent by King Frederick William IV on reforms in Prussia, an armed struggle breaks out between citizens and the military at a meeting in front of the Berlin City Palace. During the reading, after an initially peaceful atmosphere, revolutionary slogans are raised. Two shots are fired, whether intentional or the result of a misunderstanding is never clarified. What follows is a change in the mood of the demonstrators and the targeted use of the military. Fierce street and barricade fighting ensues and claims several hundred lives, according to authorities 303 people, 288 men, 11 women and 4 children.

- March 19: King Frederick William IV is forced to appear before the "March Fallen" laid out in the palace courtyard and doff his cap. On March 21, he rides through Berlin wearing a black-red-gold sash and declares that he wants Germany's freedom, Germany's unity.

- March 20: Bavarian King Ludwig I abdicates in favor of his son Maximilian II as a result of riots in Munich and other cities in Bavaria.

- 18-22 March: The popular uprising in Milan against Austrian rule in Lombardy leads to the First Italian War of Independence between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont, whose troops support the Upper Italian revolutionaries.

- 23 March: Revolution in Venice - Daniele Manin proclaims independence from Austria and declares the city a republic (cf. Repubblica di San Marco).

- 31 March to 3 April: The Pre-Parliament meets in Frankfurt am Main.

- Beginning of April: Start of the Schleswig-Holstein uprising as a result of the national German uprisings in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Both German and Danish national liberals claimed the Duchy of Schleswig, which formally still stood as a royal Danish fief in personal union with Denmark.

- April 12-20: The Republican-motivated Hecker campaign in Baden is defeated on April 20 in a battle on the Scheideck near Kandern in the Black Forest; Lieutenant General Friedrich von Gagern falls as commander of the federal troops. Friedrich Hecker goes into exile.

- April-May: Uprising of the Poznan Poles against Prussian domination led by Ludwik Mieroslawski

- 15 May: Second Viennese Uprising

- 17 May: Emperor Ferdinand I flees from Vienna to Innsbruck under the pressure of the revolutionary unrest.

- May 18: Opening of the Frankfurt National Assembly in the Paulskirche, the first all-German democratically elected parliament; it is to prepare German unity and draw up a constitution for the new unified state.

- June 2-June 12: The Slav Congress meets in Prague and calls for the transformation of the Danube monarchy of Austria "into a federation of equal peoples."

- 16 June: Suppression of the Prague Whitsun Uprising by Austrian troops

- 24 June: Suppression of the French June Uprising in Paris. Afterwards, the counter-revolution strengthens in the states of the German Confederation as well, forcing the revolutionaries increasingly onto the defensive.

- July 25: The northern Italian insurgents led by Sardinia-Piedmont are defeated by Austrian troops at the Battle of Custozza.

- 9 August: Armistice between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont

- 26 August: Armistice between Prussia and Denmark. The National Assembly must ultimately approve the Treaty of Malmö on September 16, thus revealing its own powerlessness. The crisis leads to new unrest in Frankfurt am Main (September Revolution) and other German cities.

- September 12: Republican nationalist leader Lajos Kossuth becomes prime minister of Hungary. The Austrian Emperor is denied the title of "King of Hungary". There are national revolutionary riots against Austrian domination.

- September 18: Barricade fights against Prussian and Austrian troops in Frankfurt: September Revolution

- September 21-25: 2nd Baden Uprising in Lörrach; Gustav Struve, who proclaimed the German Republic on September 21, is subsequently arrested.

- October 6-31: The October Uprising in Vienna is bloodily put down after barely four weeks by imperial troops under Prince Windischgrätz.

- November 9: Robert Blum, a member of the Frankfurt National Assembly, is shot in Vienna in the course of the reprisals against the Austrian revolutionaries in demonstrative defiance of parliamentary immunity.

- November 21: Constitution of the Centralmärzverein as a Germany-wide republican organization by deputies from various factions of the democratic left in the Frankfurt National Assembly.

- December 2: The Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I abdicates and leaves the throne to his nephew Franz Joseph I.

- December 27: The National Assembly in Frankfurt adopts the basic rights of the German people.

Revolutionary development 1849

- February-March: New uprisings in some Austrian territories in Upper Italy, in particular the revolutionary coup against Grand Duke Leopold II in Tuscany, lead to another war between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont.

- 23 March: Renewed defeat of the Upper Italian revolutionaries and Sardinia-Piemont against the Austrian army in the battle of Novara.

- March 28: After much controversy, the National Assembly adopts the Paulskirche Constitution.

- April 3: Prussian King Frederick William IV rejects the imperial crown offered to him by the National Assembly (Kaiserdeputation). German unity and the imperial constitution thus fail.

- April 14: Hungary declares its independence from Austria and proclaims a republic. This is followed by the Hungarian War of Independence against Austria.

- May: In the May Uprisings, the Imperial Constitution Campaign begins with the attempt to enforce the constitution in some states and regions of the German Confederation after all - and furthermore to install individual republics. The confrontation between revolution and reaction leads to a civil war-like escalation in some states. In addition to Saxony and Baden, for example, the Prussian Rhine province and the adjacent province of Westphalia (→ Iserlohn Uprising of 1849 and Revolution of 1848/49 in Westphalia) as well as the Palatinate (Bavaria) (Palatinate Uprising) are also centres of corresponding uprisings.

- 3-9 May: A Saxon republic is proclaimed in the Dresden May Uprising, which fails as a result of the suppression of the uprising by Prussian troops.

- 11 May: Mutiny of the Baden garrison in Rastatt: Start of the Baden May Uprising.

- 13 May: Grand Duke Leopold of Baden leaves the country.

- 1 June: The Republic is proclaimed in Baden. Lorenz Brentano assumes the presidency of the provisional government. Prussian troops begin to advance against Baden.

- June 6-18: The rump parliament, the remaining remnant of the National Assembly, meets in Stuttgart; it is dissolved by Württemberg troops on June 18.

- 23 July: Capture of Rastatt by Prussian troops, end of the Baden Revolution and symbolic end of the German Revolution of 1848/49.

Aftermath until October 1849

- 6 August: Milan Peace Treaty between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont

- 23 August: Austrian troops defeat the revolutionary Republic of Venice. Upper Italy is once again in Austrian hands.

- October 3: The last Hungarian revolutionaries surrender to the Austrians in the fortress of Komorn.

The Entry of the Pre-Parliament into the Paulskirche in Frankfurt on March 30, 1848

Dissolution of the rump parliament on 18 June 1849 in Stuttgart: Wuerttemberg dragoons disperse the demonstration of the expelled deputies (book illustration from 1893).

Laying out of the March Fallen , oil painting by Adolph Menzel, 1848

March 21, 1848: Frederick William IV, King of Prussia, proclaims the unity of the German nation in his capital, contemporary picture newspaper

Envoys to the Congress of Vienna, copperplate engraving after a drawing by Jean Baptiste Isabey, 1819

The Göttingen Seven, lithograph by Carl Rohde, 1837

Leaflet from September 1847 with the "Demands of the People", the goals of the Baden Radical Democrats as formulated at the Offenburg Assembly.

Questions and Answers

Q: In what year did the German revolutions take place?

A: The German revolutions took place in 1848.

Q: How many states were loosely bound together in the German Confederation?

A: There were 38 states that were loosely bound together in the German Confederation.

Q: Was Hungary part of the German Confederation?

A: No, Hungary was not part of the German Confederation, even though Austria was.

Q: What event served as an example for the German revolutions?

A: The French Revolution of 1848 served as an example for the German revolutions.

Q: When did the biggest successes of the German revolutions happen?

A: The biggest successes of the German revolutions happened in March in Berlin and Vienna.

Q: Where was the German National Assembly elected?

A: The German National Assembly was elected in Frankfurt am Main.

Q: Why did the Assembly slowly disintegrate afterwards?

A: Austria and Prussia withdrew their delegates from the Assembly, and the Assembly itself slowly disintegrated afterwards. Additionally, the Prussian king refused to become emperor of a united German state.

Search within the encyclopedia