Requiem

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Requiem (disambiguation).

![]()

Totenmesse is a redirect to this article. For the television film, see Tatort: Totenmesse. For Chekhov's humoresque, see The Mass of the Soul.

The Requiem (plural Requiems, regionally also Requiems), liturgically Missa pro defunctis ("Mass for the deceased"), also Sterbeamt or Seelenamt, is in the Roman Catholic Church and in the Eastern Church the Holy Mass in memory of the deceased. Often a requiem also goes back to a Mass stipend. Masses for souls (also called "Seelmessen" or "Jahrzeiten"), which have to be celebrated annually due to endowments, are recorded in yearbooks.

The liturgical form of the Mass for the Dead is the Requiem. The term refers both to the liturgy of the Holy Mass at the funeral celebration of the Catholic Church and to church music compositions for the commemoration of the dead. It is derived from the incipit of the introit Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine ("Eternal rest grant them, O Lord"). The proprium of the liturgy of the Requiem corresponds to that of All Souls' Day. It may also be taken as a votive Mass at Masses for the dead on the occasion of anniversaries or commemorations of the deceased, if no feast or commemorative day has liturgical precedence.

The Requiem celebrated by a bishop or infuled abbot is called Pontifical Requiem. The Requiem may be celebrated in immediate temporal connection with the funeral, but also independently of it at another time of day. Several forms of funeral celebration are possible for this purpose, depending on local circumstances. If the coffin can be brought into the church for the Requiem, it is placed in a suitable position in the chancel.

The Requiem in the Catholic Liturgy

Previous story

Eucharistic funerals are already documented in the Acts of John at the end of the second century. At the beginning of the third century, Tertullian mentions the commemoration of the dead on the anniversary with the oblationes pro defunctis (in German: Entrichtungen für Verstorbene) in his work De corona militis (On the Wreath of the Soldier). In the late fourth century, liturgical commemoration of the dead is mentioned in the Apostolic Constitutions (8th book, chapter 12). At the end of the fifth century, the commemoration of the dead also appears as a litany in the Deprecatio Gelasii of Pope Gelasius. In the seventh-century collection of liturgical prayers Sacramentarium Leonianum, five forms of Mass prayers super defunctos (in German: über Verstorbene) and a special form of Hanc ígitur oblationem (Accept graciously these gifts) are found in the Mass canon. The Missal of the Abbey of Bobbio from the early tenth century also knows the care of the dead.

Proprium

The various local variants of the commemoration of the dead were unified by the Proprium in the wake of the Council of Trent (1545) and established by Pope Pius V's Missale Romanum in 1570. Some minor changes resulted from the apostolic constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium of the Second Vatican Council. In its liturgical constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium (no. 81), the Council determined that the liturgy for the dead should "express more clearly the paschal meaning of Christian death." Since then, the form of the Office of the Resurrection has also come into use in the Catholic Church.

The liturgical sequence of a Requiem is similar to that of Holy Mass on weekdays during penitential seasons (Advent, Lent). The Gloria, which is intended for joyful and festive occasions, and the Credo of Sundays and feasts are omitted. The Hallelujah is replaced by a Tractus, which was formerly followed by the Dies irae sequence; this is no longer an integral part of the Requiem.

The proprium of the Mass for the dead outside of Lent is as follows:

- Introit: Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

- Gradual: Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

- Tractus: Absolve domine

- Offertory: Domine Jesu Christe

- Communio: Lux aeterna

Before the liturgical reform of 1970, the Agnus Dei had a different version from the text of the Ordinary. Instead of the twice repeated miserere nobis and dona nobis pacem, Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem used to be sung three times in the Requiem; on the third occasion a sempiternam was added to this line for affirmation. This deviation was justified by the idea that the salvific effect of the requiem mass should be given to the deceased alone, which is why the prayer is not addressed to the praying persons themselves ("Have mercy on us"), but to the dead ("Give them (eternal) rest"). Other deviations (such as the omission of the final blessing) also had their justification in this. Today the Agnus Dei is also sung in the Requiem in the version of the Ordinary.

The opening words Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine express the character of the Mass for the Dead, the supplication of the living for the salvation of the deceased. The two texts that recur in the Proper of the Mass for the Dead, Requiem aeternam dona eis and lux perpetua luceat eis, are based on the two verses 34 and 35 from the second chapter of the apocryphal fourth book of Ezra requiem aeternitatis dabit vobis and quia lux perpetua lucebit vobis per aeternitatem temporis, which were probably written around 100 AD.

| Original text (Latin) | Translated text |

| I. IntroitusRequiem |

|

| II GradualeRequiem |

|

Measurement series

Already established in the visions of Pope Gregory I is the custom of celebrating a series of masses for the dead on several consecutive days. From this developed the Gregorian Mass series celebrated to varying degrees.

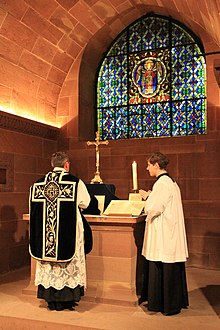

Requiem in the crypt of the Strasbourg Cathedral

.jpg)

The Introit Requiem aeternam in the Liber Usualis

The Requiem in music

Components

As the first piece of the musical Mass proprium, the Introit was usually set to music by the composers, as was the Offertory, in contrast to the Sequence, which is occasionally shortened or omitted altogether for various reasons (time, extent).

In old requiem compositions, the accompanying unaccompanied and monophonic Gregorian chant is the basis of the composition, as it still is with Alessandro Scarlatti and even Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (quotation of the tonus peregrinus in the first movement (Requiem aeternam) to the text Te decet Hymnus deus in Sion (soprano solo)). Maurice Duruflé's Requiem is based on Gregorian melodies. Altuğ Ünlü has integrated the Gregorian Graduale Clamaverunt justi of the time in the cycle of the year into the first movement of his Requiem.

As a rule, settings of the Requiem consist of the following sequence of movements, in which texts of both the Proprium and the Ordinary are set to music:

- Introit: Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

- Kyrie

- Sequence: Dies irae

- Offertory: Domine Jesu Christe

- Sanctus and Benedictus

- Agnus Dei

- Communio: Lux aeterna

The sequence is often divided into several movements. As a special feature of the French rite, a Pie Jesu (last half verse of the Dies Irae) is added as an independent movement (before the Agnus Dei or between the Sanctus and Benedictus), sometimes omitting the sequence (e.g. Gabriel Fauré, Maurice Duruflé, but also - though not French - Cristóbal de Morales, John Rutter), sometimes additionally (e.g. Marc-Antoine Charpentier), thus setting the text to music twice.

| Original text (Latin) | Translated text |

| Pie Jesu, Dominedona | Good Jesus, Lord, |

Many composers, e.g. Gabriel Fauré and Giuseppe Verdi, also set the responsory Libera me from the liturgy of the church funeral service to music.

| Original text (Latin) | Translated text |

| Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna, | Save me, O Lord, from eternal death in |

Many composers set the hymn In paradisum (e.g. Gabriel Fauré) to music for the finale, also from the exequia.

Soundtracks

See also: List of Requiem settings

While in the period of Viennese Classicism the Requiem certainly still had the function of a musical accompaniment to the church service (e.g. in the works of Antonio Salieri, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, Joseph Martin Kraus, François-Joseph Gossec, Michael Haydn, Luigi Cherubini), the setting gradually began to detach itself from ecclesiastical ties. Even Hector Berlioz's monumental and large-scale work was conceived more for the concert hall. The corresponding compositions by Louis Théodore Gouvy, Antonín Dvořák, Giuseppe Verdi and Charles Villiers Stanford, in which the orchestra is assigned an increasingly important role, are also in this tradition. However, there are also works with smaller instrumentation from this period which are still designed for use in church, for example by Anton Bruckner, Franz Liszt, Camille Saint-Saëns and Josef Gabriel Rheinberger. Between these poles stands Felix Draeseke, who created both a symphonic and an a cappella Requiem.

The German Requiem by the Protestant Johannes Brahms uses freely chosen texts from the Luther Bible, not those of the Catholic liturgy, whereas the Estonian Cyrillus Kreek's Reekviem of 1927, a work commissioned by the Lutheran Church in Estonia, drew on the Latin Requiem but incorporated variations, such as the Westminster Chime or the suggestion of the chorale Christ ist erstanden. From the time of the late Romantic period onwards, the number of Requiem compositions dwindled noticeably. The importance of the text recedes in many settings in favor of the increasingly symphonic treatment of the large orchestral apparatus, as in Max Reger and Richard Wetz. These works are conceived exclusively as concert music and can only be used as such. Others emphasize the text and give their works a liturgical character again (e.g. Gabriel Fauré and Maurice Duruflé, who both omit the Dies Irae).

The Requiem still plays a significant role in modern music. In Benjamin Britten's setting of War Requiem, the words of the liturgy are combined with poems by the English poet Wilfred Owen. Other important compositions after the Second World War were created by Boris Blacher, György Ligeti, John Rutter, Krzysztof Penderecki, Rudolf Mauersberger, Paul Zoll (who used a German text consisting of excerpts from Ernst Wiechert's requiem mass) and Heinrich Sutermeister, Joonas Kokkonen, Riccardo Malipiero, Günter Raphael and Manfred Trojahn. Bernd Alois Zimmermann's Requiem für einen jungen Dichter (Requiem for a Young Poet), based on texts by various poets, reports and reportages, occupies a special position. Increasingly, compositions without text are appearing with the title Requiem, such as that by Hans Werner Henze, set in the form of nine sacred concertos for solo piano, concert trumpet and large chamber orchestra. On the occasion of the 100th commemorative year (2014) after the beginning of the First World War, the Ligeti student Altuğ Ünlü composed a Requiem. The "Requiem X" by the Swiss composer Christoph Schnell occupies a special position among modern requiem compositions: it is the only requiem directed by the composer that has been filmed.

The Requiem by British composer Andrew Lloyd Webber won the Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition in 1986. Georges Delerue set the Requiem's Introit and Libera me to music for the 1991 film Black Robe.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a Requiem?

A: A Requiem (or Requiem Mass) is a Eucharist service in the Roman Catholic Church to pray for the repose of the soul of someone who has died.

Q: What language are the words of a Requiem Mass?

A: The words of a Requiem Mass are in Latin.

Q: When did Celebration of the Eucharist to pray for people who have died begin?

A: Celebration of the Eucharist to pray for people who have died goes back at least as far as the 2nd century.

Q: Who wrote polyphonic settings of the Requiem Mass during the Baroque period?

A: During the Baroque period, composers such as Johannes Ockeghem wrote polyphonic settings of the Requiem Mass.

Q: Which composer wrote one of greatest pieces ever written?

A: Mozart wrote one of greatest pieces ever written, an 18th century requiem.

Q: Who rearranged some text from traditional Latin words in his Messa da Requiem?

A: Giuseppe Verdi rearranged some text from traditional Latin words in his Messa da Requiem (1874).

Q: What is unusual about Brahms' work "Ein Deutsches Requiem"?

A

Search within the encyclopedia