Reptile

The reptiles or creepers (taxon: Reptilia, lat. reptilis "creeping") are a differently defined group of tetrapods, which - depending on the systematics (class or clade) - includes different groups of amniotes.

According to the traditional view, the reptiles (Reptilia) are a class of vertebrates at the transition from the "lower" (Anamnia) to the "higher" vertebrates (mammals and birds). However, the modern view is that they are not a natural group as such, but a paraphyletic taxon because they do not contain all the descendants of their last common ancestor. The classical taxon Reptilia is therefore considered obsolete and is rarely used in zoological and paleontological systematics. The taxon name is now mostly used as an informal collective term for terrestrial vertebrates with similar morphology and physiology (see Characteristics). In this sense, 11,440 recent reptile species are currently distinguished.

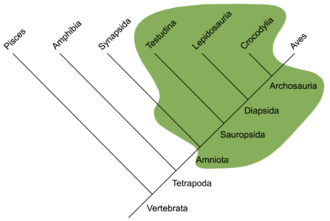

From a cladistic point of view, which is the scientific standard today, the reptiles as a monophyletic taxon, i.e. as a natural (complete) descent group (Reptilia as a clade), would have to include at least the birds as well, and, taking into account certain extinct forms ("mammal-like reptiles" such as Dinocephalia), even the mammals. To reflect these ratios, the taxon Amniota, introduced as early as 1866 and now defined as a clade, is used to include all recent reptiles, including mammals and birds, as well as all now-extinct descendants of their last common ancestor. The Sauropsida, introduced in 1864 and now also defined as a clade, includes all recent reptiles, including birds, and all extinct forms that are more closely related to modern reptiles and birds than to mammals. In fact, all recent reptiles are more closely related to birds than to mammals, meaning that all reptiles in the lineage leading to mammals are now extinct. Starting in the late 1980s, various scientists attempted a phylogenetic definition of the taxon Reptilia in order to make it more scientifically useful. Particularly in scientific publications from the English-speaking world, Reptilia is now sometimes used synonymously with the clade Sauropsida.

The scientific study of reptiles falls into the field of herpetology. The knowledge about their care and breeding in terrariums is called terraristics or terrarium science, which is a part of vivaristics.

Extent of reptiles in the traditional understanding (green area), shown in a cladogram. Note that birds are excluded, but at least in traditional palaeontological systematics the extinct early representatives of the lineage to which mammals belong (Synapsida) are also considered reptiles.

Features

The most characteristic feature of recent reptiles (here meant as non-bird sauropsids) is their dry, mucus-less body covering consisting of horny scales. They differ from birds and mammals in the absence of feathers and hairs, respectively. In pangolins, the horny scales usually overlap like roof tiles, but in turtles and crocodiles they do not. A "real" moult (ecdysis), the periodic stripping off of larger connected parts of the epidermis, occurs in principle only in pangolins and especially pronounced in snakes.

Most reptiles living today have a typical lizard-like habitus, that is, they have a long tail, walk on four legs (quadrupeds), and move in a straddling gait. This is the original habitus of terrestrial vertebrates, which was already present in the ancestors of reptiles. All snakes and some lizards deviate from this primitive plan in that their legs and limb girdles are regressed and the neck, trunk, and tail merge without appendage. Also relatively derived recent reptiles are the turtles, in which the ribcage and trunk scaling, especially in the tortoises, form a kind of shell into which they can retreat. The lizard-like habitus of crocodilians, however, is not inherited from their ancestors, but acquired secondarily (see History of Descent). This is shown, among other things, by the fact that when crocodiles run fast, they do not curl their trunks in the horizontal plane, unlike lizards, and place their legs under their bodies.

Unlike amphibians, all reptiles, like birds and mammals, are lung breathers throughout their lives, so they do not go through an aquatic, gill-breathing larval stage.

Most recent forms lay eggs (oviparity), only a few give birth to live young (viviparity) or are oviparous (ovoviviparity). The eggs are encased in a parchment-like, flexible shell in most pangolins. In contrast, the eggs of many turtles and all crocodilians have a relatively firm calcified shell. The degree of calcification is considered to be the degree of adaptation to fluctuating conditions with respect to the moisture of the environment in which the egg is laid: Eggs with the most calcified shell are best protected against both water penetration and desiccation.

Recent reptiles are ectothermic and poikilothermic animals that regulate their body temperature as much as possible through behaviour (e.g. sunbathing). Furthermore, the blood circulation of all recent reptiles does not show a complete separation of lung and body circulation. In most forms, this is realized by a non-continuous cardiac septum. Crocodilians, on the other hand, have a closed cardiac septum and blood exchange occurs in the aortic trunk through an opening in the partition between the left and right aorta (foramen panizzae).

Close-up of the horny scales on the back of representatives of various species of the genus Plica (family Kiel's-tailed iguanas)

Eggs of the corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) with hatching juveniles

Ancestry

The phylogenetically first reptiles are at the same time also the phylogenetically first amniotes, respectively the earliest amniotes are consistently reptilian forms. They have been fossilized for the first time from the early Upper Carboniferous, a time about 315 million years ago. All amniotes, and thus all reptiles, are descended from original terrestrial vertebrates ("amphibians" in the broader sense). Unlike reptiles, these amphibians did not reproduce via an amniotic egg, a type of autonomous survival capsule that provides nutrients to the developing embryo or fetus and protects it from desiccation. Amniotes, unlike amphibians, are therefore not dependent on bodies of water for reproduction and are thus generally better adapted to dry habitats. With modern amphibians, at least one lineage of the original terrestrial vertebrates has survived to the present day, but these are predominantly specialized in wet habitats and cannot be compared with the immediate ancestors of the amniotes or reptiles, which must already have been relatively independent of water (see → Reptiliomorpha).

While the skeletal remains of the first "true" reptile Hylonomus have survived in a fossil tropical humid forest ("coal forest"), trace fossils of about the same age (ca. 315 million years) show the existence of early amniotes in an environment at least seasonally poor in water, in which the amniotic egg very likely meant a reproductive advantage.

The Amniota were already split into two main lineages in the Upper Carboniferous: One lineage, called Synapsida (see Systematics), led to the mammals and the other lineage, called Sauropsida, led to the recent reptiles and the birds. In the traditional paleontological understanding, the early representatives of the synapsid lineage ("pelycosaurians" and early therapsids) are also counted among the reptiles.

The sauropsids, in turn, were already split into two main lineages in the Upper Carboniferous: Parareptilia and Eureptilia, with the oldest known Parareptilia dating from the highest Upper Carboniferous, some 15 million years younger than Hylonomus, the first Eureptilia. The parareptiles have no recent representatives, for with the Procolophonida the last of their subgroups became extinct in the late Triassic. Among the most popular parareptiles are the pareiasaurs, already extinct again in the Permian.

Consequently, most postpermian and all recent reptiles (as well as birds) are representatives of the Eureptilia. Almost all Eureptilia and all recent representatives belong to a large group called Diapsida (see systematics). Although their earliest representatives also appear in the Upper Carboniferous, they do not come to flower until the Mesozoic, which earns this era of geological history the nickname "Reptilian Age".

In many Mesozoic diapsids, the original lizard-like habitus underwent a marked change: the dinosaurs switched to bipedal locomotion, the pterosaurs developed wings, and several groups adapted to life in the sea, converting their limbs into fins. The most significant adaptation in this respect occurred in the ichthyosaurs, which developed a fish-like habit, similar to modern dolphins.

The representatives of the diapsid lineage leading to the dinosaurs and pterosaurs, among others, are called archosaurs (Archosauria). Their roots lie in the Permian. In the Mesozoic, they underwent a development in which these forms lost more and more characteristics that are now considered typical of reptiles. They develop a separation of lung and body circulation, become endothermic and cover their skin with insulating material to better retain the self-generated body heat (see also feathered dinosaurs). While in the traditional understanding dinosaurs are once again a paraphyletic group with predominantly reptilian representatives and thus completely extinct, in the modern view they include birds as a monophyletic taxon, the current endpoint of the described "de-vegetation trend". A similar development already occurred in the Permian and Triassic with the synapsids and ultimately led to the mammals. However, in the evolutionary lineage of crocodilians, another lineage of archosaurs, this trend is reversed and their representatives become increasingly reptilian again compared to their ancestors (see → Crocodylomorpha).

Opposite the archosaurs are the scaled lizards (Lepidosauria), which together with the tuataras, lizards, monitor lizards, geckos, chameleons, snakes, etc. comprise by far the largest part of the recent reptiles. Although they exhibit many "primitive" features, i.e., those now considered typical of reptiles, most recent lepidosaur groups are relatively young phylogenetically, appearing no earlier than the Cretaceous.

For a long time, the systematic position of the turtles (Testudinata) was unclear: their skulls do not have temporal windows, which is why this group is traditionally assigned to the anapsids (see systematics). In the meantime, however, it is increasingly accepted that turtles are descendants of diapsid reptiles that have secondarily closed their temporal openings. Within the diapsids, both a closer relationship with the archosaurs and a closer relationship with the pangolins are discussed. The oldest known turtle fossils to date, which date from the Upper Triassic, do not allow any clarification in this regard.

Live reconstruction of Protorothyris, a lizard-like basal reptile from the Early Permian of Texas.

Dinosaurs are probably the most popular extinct reptiles.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a reptile?

A: A reptile is one of the main groups of land vertebrates that have scaly skin, lay cleidoic eggs, excrete uric acid, and have a cloaca.

Q: Are birds considered reptiles?

A: Birds evolved from dinosaurs but are not considered reptiles.

Q: Why are they called reptiles?

A: The name "reptile" comes from Latin and means "one who creeps."

Q: What is a cloaca?

A: A cloaca is a shared opening for the anus, urinary tract and reproductive ducts, found in reptiles and birds.

Q: Do reptiles have the same heart arrangement as mammals?

A: No, reptiles have a different heart arrangement and major blood vessels than mammals.

Q: What extinct reptile examples are given in the text?

A: Some extinct reptile examples given in the text are mosasaurs and dinosaurs, whose feathered descendants are birds.

Q: What is the study of living reptiles called?

A: The study of living reptiles is called herpetology.

Search within the encyclopedia