Renaissance

![]()

This article is about the Renaissance as an epoch in cultural and art history; for other meanings see Renaissance (disambiguation).

Renaissance [rənɛˈsɑ̃s] (borrowed from French renaissance "rebirth") refers to the European cultural epoch during the transition from the Middle Ages to modern times. It was characterized by the revival of the cultural achievements of Greek and Roman antiquity, which became the benchmarks for Renaissance works by scholars and artists that followed on from them. Compared to the Middle Ages, groundbreaking new perspectives emerged, especially for the image of man, for literature, sculpture, painting and architecture. The epoch designation itself has only existed since the 19th century.

In art history, the core period of the Renaissance is considered to be the 15th (Quattrocento) and 16th centuries (Cinquecento). The temporal extent of the Renaissance era, which started from the rival city republics of northern Italy, is explained not least by the time-delayed spread - with different characteristics in each case - in the countries north of the Alps. Letterpress printing, which first appeared there, is considered the most important technical achievement of the Renaissance. In this context, the epochal concept of the Renaissance in Protestant northern Europe is overlaid by that of the Reformation. The late Renaissance is also called Mannerism and was replaced by the Baroque in Italy at the beginning of the 17th century.

The pioneers of the Renaissance were humanist scholars who made antique writings, literature and other sources accessible to the present day because they saw them as guiding principles to be followed. This gave rise to a humanist educational programme which, in order to achieve optimal development, focused on a combination of knowledge and virtuous activity or on a contemplative existence devoted to research and knowledge - depending on individual possibilities and socio-political constellation. The diversity of individual possibilities for development became characteristic of the image of man in the Renaissance. The human being with his language and history was at the centre of humanist reflections.

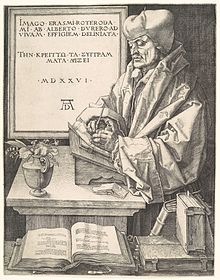

In the literary field, the Renaissance ranges from Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy to William Shakespeare's works. Donatello, Michelangelo and Tilman Riemenschneider, for example, are known as outstanding sculptors. A newly developed means of design in painting was the use of central perspective. Among the most important painters of the Renaissance are Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian and Albrecht Dürer. Big names in Renaissance architecture include Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, and Andrea Palladio. Niccolò Machiavelli stands out as a political theorist of supra-temporal importance, and Erasmus of Rotterdam as a widely communicated time-critical thinker. In music, the era is associated above all with increased polyphony and new harmony, for example in the work of Orlando di Lasso.

Dutch Renaissance in Antwerp: the City Hall (completed around 1564)

The Renaissance metropolis of Florence, situated on the Arno River

Conceptual-temporal classification

The Renaissance has only been established as a period designation in the sense of historical periodization since the middle of the 19th century. Jules Michelet, who gave the ninth volume of his Histoire de France, published in 1855, the title Renaissance, as well as Jacob Burckhardt, who published his work Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien in 1860, contributed significantly to this. Burckhardt's account focused mainly on the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, while Michelet's emphasis was on the sixteenth century: the clash of Italian and French culture in the course of warlike entanglements.

The Renaissance humanists applied the paradigm of rebirth to diverse fields of application such as the art of eloquence, the breadth of literary creation, and also to historiography along with the political-theoretical approaches it contained. History was increasingly, though not entirely, detached from cosmological cycles or a theological history of salvation and assigned to man - "concentrated on the self-fulfillment of the human".

The idea of living in a new age, distinct from the Middle Ages, had already spread among humanists, writers and artists in Italy since the 14th century. It was conceptually fixed as Rinascimento in 1550 by the Italian artist and artist biographer Giorgio Vasari, who meant the overcoming of medieval art by recourse to antique models. Vasari distinguished three ages of art development:

- the glorious age of Greco-Roman antiquity,

- an intermediate age of decay, which can be roughly equated with the epoch of the Middle Ages,

- the age of the revival of the arts and the rebirth of the ancient spirit in the Middle Ages since about 1250.

According to Vasari, the Italian sculptors, architects and painters of the second half of the 13th century, including Arnolfo di Cambio, Niccolò Pisano, Cimabue or Giotto, had already "in the darkest times shown the masters who came after them the path that leads to perfection".

In common usage today, the Renaissance in itself marks the epoch at the transition to the modern era. But one also speaks of a Renaissance in certain other contexts, when old values, ideas or patterns of action re-emerge. The Carolingian Renaissance, for example, refers to the return to antiquity that began under Charlemagne around 800. In the more recent past, when regional cultures have become more interested in their own characteristics (and languages), the term Renaissance is sometimes used, as in the case of the Irish Renaissance.

Raphael: School of Athens, 1509-1510, Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican City State

Philosophy

→ Main article: Philosophy of the Renaissance and Humanism

The philosophy of the Renaissance was also characterized by reference to ancient thinkers and by the examination of their rediscovered writings. It set the course for overcoming scholasticism and for a reorientation of the view of the world and of man, and especially of the ethical foundation. The works of Plato and Neoplatonism offered various aspects of orientation and connection for the compatibility with Christian theology. This becomes clear, for example, in the teachings of Nicolaus Cusanus, who sometimes appears as the embodiment of the "epochal threshold" between the Middle Ages and modernity.

Other accents were already set early by the anti-Christian Georgios Gemistos Plethon and Biagio Pelacani da Parma with his thinking "at the limits of atheism". This is exemplified, according to Thomas Leinkauf, by the sentence, "Thou art none other than thyself," which Pelacani declared could not be refuted, either by a finite or an infinite power. "Already here, then," Leinkauf said, "the infinite power of God can do nothing against the rightness and truth of this certainty that one is oneself." In general, the human individual as a free and self-responsible person with his or her possibilities of will, action, and design moved to the center of philosophical thought during the Renaissance. It stood, among other things, for "the multiplicity, variance, variegation of being". Significant is the ongoing reflection on the position and dignity of the human being in letters, poetry, treatises, commentaries and other written testimonies. In comparison with the ancient and patristic tradition, the focus was on action as an expression of self-preservation and self-realization - a turning to the practice of life and the problems it poses.

For Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, the most famous of the interpreters of human dignity at the time, it was a matter of making of oneself what one determines by one's own insight and the free will based on it. Giannozzo Manetti attributed to human beings on earth an almost divine position, seeing in them "as it were the lords of all and the cultivators of the earth". That human individuals on their own, however, are incapable of anything, but require education by others, was pictorially emphasized by Erasmus of Rotterdam, who wrote, for example, that no bear cub is so misshapen as man is born raw in spirit. "Unless thou form and shape him with much zeal, thou art the father of a freak, not of a man." And further, "If thou art foolish, thou hast a wild beast; if thou art watchful, thou hast, as it were, a deity."

Ethical reflections - philosophical discipline since Plato and Aristotle up to the scholastic authors of the Trecento - remained present throughout the Renaissance. On the one hand, Aristotelian ethics continued to function as a basic norm and standard; on the other hand, like other parts of Aristotelian doctrine, it was fundamentally criticized and replaced by a new type of individualistic morality, more Stoic, Epicurean, or Averroistic in character, as for example in Michel de Montaigne and Giordano Bruno. Whereas for Petrarch it was above all the individual intention to act that counted as a standard of goodness, Machiavelli directed attention primarily to the relationship between ends and means, thus making a philosophically significant break with tradition: in his view, good could also be brought about by bad means, while bad, even malicious ends could be realized by good deeds. For Machiavelli, the Aristotelian ethical concept failed in the face of reality. It was right to strive for the "middle way" between the extremes; however, excess was part of human nature, was therefore unavoidable and could only be mitigated.

Coluccio Salutati as well as Leonardo Bruni attested to man's insatiable thirst for knowledge, which leaves nothing out and extends to all disciplines. The recovery of ancient writings and their utilization by the Renaissance humanists in many areas of life was accompanied by a sudden expansion of the body of knowledge, which had to be organized scientifically and methodically and examined with regard to its usability in conformity with reality. Fundamentally developed by Cusanus, the unlimited became the unifying ground of all thought. For Hanna-Barbara Gerl, the "setting into one of unity and infinity" is "the step catapulting out of the old world views into the modern era." With this, reason experiences its non-knowledge, its inadequacy vis-à-vis the infinite. But within the limit of the finite, "thinking could now set its starting point at will and behave in a relative-measuring way (according to the self-chosen measure). Thinking becomes measuring, mens equals mensura; weight, measure, and number become the instrument and expression of self-assertion in the finite."

Erasmus portrayed by Albrecht Dürer (1526)

Questions and Answers

Q: What does the word "Renaissance" mean?

A: The word “Renaissance” is a French word for “cultural rebirth.”

Q: What was rediscovered during this period?

A: During this period, there was a “rebirth” of classical learning. People started relearning the teachings of scholars from Ancient Greece, Rome, and other ancient societies.

Q: Who is considered to be the most famous Renaissance man?

A: The most famous Renaissance man is Leonardo da Vinci, who was a painter, a scientist, a musician and a philosopher.

Q: Where did the Renaissance start?

A: The Renaissance started in Italy.

Q: How is the Italian Renaissance divided?

A: In Italy, the period is divided into three parts - Early Renaissance, High Renaissance and Late Renaissance (also called the Mannerist period).

Q: When did Baroque period begin?

A: Following the Mannerist period was the Baroque period which began around 1600.

Q: Is it easy to tell where one era ends and another begins outside of Italy?

A: Outside Italy it can be hard to tell where one era ends and another begins.

Search within the encyclopedia