Religion

Religion (from Latin religio 'conscientious consideration, care', to Latin relegere 'to consider, to give heed', originally meaning "conscientious care in the observance of omens and precepts") is a collective term for a variety of different world views, the basis of which is the respective belief in certain transcendent (supernatural, supernatural, supersensible) forces and often also in sacred objects.

The teachings of a religion about the sacred and transcendent are not provable in the sense of scientific theory, but are based on the belief in communications of certain mediators (founders of religions, prophets, shamans) about intuitive and individual experiences. Such spiritual communications are called revelation in many religions. Statements about spirituality and religiosity are views without need for explanation, which is why religions put them into parables and symbol systems in order to be able to bring their contents closer to many people. Skeptics and critics of religion, on the other hand, seek only controllable knowledge through rational explanations.

Religion can normatively influence value concepts, shape human behaviour, actions, thinking and feeling, and in this context fulfil a number of economic, political and psychological functions. These comprehensive properties of religion bear the risk of the formation of religious ideologies.

In the German-speaking world, the term religion is mostly used to refer to both individual religiosity and collective religious tradition. Although both areas show enormous diversity in human thought, some universal elements can be formulated that are found in all cultures of the world. In summary, these are the individual desires to find meaning, moral direction, and explanation of the world, as well as the collective belief in supernatural powers that in some way influence human life; also the quest to reunite this worldly existence with its otherworldly origin. However, these standard explanations are sometimes criticized.

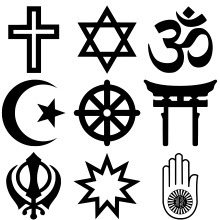

The world's largest religions (also known as world religions) are Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism, Sikhism, Jewish religion, Bahaism and Confucianism (see also: List of religions and worldviews). The number and richness of forms of historical and contemporary religions far exceeds the number and richness of forms of world religions.

Pre-modern cultures invariably had a religion. Religious worldviews and systems of meaning often have long traditions. Several religions have related elements, such as communication with transcendent beings within the framework of doctrines of salvation, symbol systems, cults and rituals, or build on each other, such as Judaism and Christianity. The creation of a well-founded systematics of religions, which is derived from the relationships between the religions and their history of origin, is a demand of religious studies that has not yet been fulfilled.

Some religions are based on philosophical systems in the broadest sense or have received such systems. Others are more politically, sometimes even theocratically oriented; still others are based primarily on spiritual aspects. Overlaps can be found in almost all religions, and especially in their reception and practice by individuals. Numerous religions are organized as institutions; in many cases one can speak of a religious community.

Religious studies, history of religion, sociology of religion, ethnology of religion, phenomenology of religion, psychology of religion, philosophy of religion, and in many cases sub-fields of theology are particularly concerned with the scientific study of religions and (in part) religiosity. Concepts, institutions and manifestations of religion are questioned selectively or fundamentally by forms of criticism of religion.

The adjective "religious" must be seen in the respective context: It denotes either "the reference to (a particular) religion" or "the reference to a person's religiosity".

Symbols of some religions: Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, Shintō, Sikhism, Bahaism, Jainism.

Definition attempts

There is no generally accepted definition of religion, but only various attempts at definition. Roughly, substantialist and functionalist approaches can be distinguished. Substantialist definitions try to determine the essence of religion, for example, in its relation to the sacred, the transcendent or the absolute; according to Rüdiger Vaas and Scott Atran, for example, the relation to the transcendent represents the central difference to the non-religious.

Functionalist concepts of religion attempt to define religion on the basis of its community-creating social role. In many cases, the definition is made from the perspective of a particular religion, for example Christianity. One of the most famous and often quoted definitions of religion comes from Friedrich Schleiermacher and reads: Religion is "the feeling of the absolute dependence on God". The definition from the point of view of a Jesuit is: "Worship of spiritual personal beings, standing apart from and above the visible world, on whom one believes oneself to be dependent and whom one somehow seeks to make favorable".

A substantialist definition, for example according to the Protestant theologian Gustav Mensching, reads: "Religion is an experiential encounter with the sacred and responding action of the human being determined by the sacred." According to the religious scholar Peter Antes, religion is understood to mean "all ideas, attitudes, and actions toward that reality which people accept and name as powers or might, as spirits or also demons, as gods or God, as the sacred or absolute, or finally also only as transcendence."

Michael Bergunder divides the term into Religion 1 and Religion 2. Religion 1 can be understood as the attempts of religious studies to define the term precisely. Religion 2, on the other hand, refers to the everyday understanding of religion. However, there are interactions between these two definitions, so that a clear distinction cannot be made. Bergunder historicizes the concept of religion and therefore criticizes it at the same time. So there is a difference in the understanding of religion on the meta-level (true philosophically) and in experience (anthropologically).

Clifford Geertz and Gerd Theißen

Gerd Theißen defines religion, following Clifford Geertz (1966), as a cultural sign system:

"Religion is a cultural sign system that promises life gain through correspondence to an ultimate reality."

- Gerd Theißen: The Religion of the First Christians. A Theory of Early Christianity.

Theißen (2008) simplifies Geertz's definition by speaking of sign system instead of "symbol system". According to Geertz (1966) a religion is:

- a symbol system that aims to

- to create strong, comprehensive and lasting moods and motivations in people,

- by formulating notions of a general order of being, and

- surrounds these ideas with such an aura of factuality that

- the moods and motivations seem to correspond completely to reality.

Geertz developed the theory of interpretative or symbolic anthropology in his writings (density description), he is considered a representative of a functional concept of religion, that is, he did not deal with the question of what the essence or substance of religion was (in the sense of a substantial concept of religion), but what its function is for the individual and society. For him, religion was a necessary cultural pattern. Geertz saw in religion a system of meaning and orientation and ultimately a conflict resolution strategy, because religions provide a general order of being and a pattern of order, and through them no event remains inexplicable.

Theißen justifies this by arguing that symbols in the narrower sense are merely a particularly complex form of sign and that Geertz's formulation of the description of the "correspondence of moods and motivations to a factually believed order of being" finds expression in an equally differentiated way in the "correspondence to an ultimate reality". Theissen's definition now allows for the following analysis:

- cultural sign system, says something about the essence of religion;

- Sign system corresponds to an ultimate reality, says something about effect;

- Sign system promises life gain, says something about the function.

| Religion as an ordering force | Religion as crisis management | Religion as crisis provocation | |

| cognitive | Building a cognitive order: man's place in the cosmos | Coping with cognitive crises: The irritation caused by borderline experiences | Provocation of cognitive crises: The Intrusion of the Whole-Other |

| emotional | Building basic emotional trust in a legitimate order | Coping with emotional crises: Fear, guilt, failure, grief | Provocation of emotional crises: through fear, guilt, etc. |

| pragmatic | Building accepted ways of life, their values and norms | Coping with crises: Conversion, Atonement, Renewal | Provocation of crises: through the pathos of the unconditional |

Universal elements of the religious

The Austrian ethnologist, cultural and social anthropologist Karl R. Wernhart has classified the basic structures of the "religious per se" (Religious Beliefs per se), which are common to all religions and cultures - regardless of their constant change - as follows:

Faith

- Existence of incorporeal, supernatural "force fields" (souls, ancestors, spirits, gods)

- Some religions assume the existence of one or more personal or impersonal transcendent powers (e.g. one or more deities), spirits or laws (e.g. Dao, Dharma) and make statements about the origin and destiny of man, for example about Nirvana or the afterlife.

- Connection of the human being with the transcendent in a holistically interwoven dimension of relationship that transcends normal human consciousness and is sanctified

- All ethics and morality are causally rooted in the respective world of belief

- Man is more than his purely physical existence (has a soul, for instance)

Orientation

Answers to the metaphysical "cardinal questions of life": (Italics = Wernhart quotes the "Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions" of the 2nd Vatican Council of 1962-1965)

- Where do we come from? (What is the human being? What is the meaning and purpose of life?)

- Creation myths - which are often transformed and kept alive with the help of drama, music, rites or dances - thereby form a vehicle everywhere for recording historical events in a timeless dimension. Myth is the way in which the world is explained, legitimized and evaluated.

- Where do we stand in the world? (What is the good, the evil, [...]? Where does suffering come from and what is its meaning)?

- Where are we going? (What is the path to true happiness?)

- What is the final goal we have in mind? (What is that final and ineffable mystery of our existence [...]?)

Safety aspect

Many scholars (such as A. Giddens, L. A. Kirkpatrick, A. Newberg and E. d'Aquili) emphasize the aspect of security for the individual or his neighbors in relation to orientation. In their view, religions satisfy the need for succor and stability in the face of existential anxieties; they offer comfort, protection, and clarification of meaning in the face of suffering, illness, death, poverty, misery, and injustice. According to Kirkpatrick's attachment theory, God is a substitute attachment figure when human attachment figures (parents, teachers, and the like) are absent or inadequate. This assumption could be empirically supported by R. K. Ullmann.

Boyer and Atran criticize the functions of security and orientation. They counter that religions often raise more questions than they answer, that the idea of redemption is often absent, that despite official religions, belief in evil spirits and witches is common, and that even many denominations not only reduce fears but also create new ones. The two scholars, unlike Wernhart, reduce universals to two human needs: Cooperation and Information.

Expressions

Every believer has expectations, hopes and aspirations which, against the background of faith and religious orientation, find expression in various practices:

- Prayers of supplication or thanksgiving and dialogue with the Transcendent

- ritual acts (rites, sacrifices, ceremonies, etc.)

- Asceticism, ecstasy, meditation, mysticism

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a religion?

A: A religion is a set of beliefs about the origin, nature, and purpose of existence, usually involving belief in supernatural entities such as deities or spirits that have power in the natural world.

Q: What are religious practices?

A: Religious practices are rituals and devotions directed at the supernatural.

Q: Do religions believe in the spiritual nature of humans?

A: Yes, many religions believe in the spiritual nature of humans.

Q: How many different religions or sects exist?

A: There are many different religions or sects, each with its own set of beliefs.

Q: Are some beliefs concerned with moral behavior?

A: Yes, some beliefs are also concerned with the moral behavior of humans.

Q: What type of power do deities or spirits have in the natural world?

A: Deities or spirits have power over events and forces in the natural world according to some religious beliefs.

Search within the encyclopedia