Red Army Faction

![]()

RAF is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see RAF (disambiguation).

The Red Army Faction (RAF) was a left-wing extremist terrorist organization in the Federal Republic of Germany. It was responsible for 33 or 34 murders of political, business and administrative leaders, their drivers, police officers, customs officials and American soldiers, as well as for the Schleyer kidnapping, several hostage-takings, bank robberies and explosive attacks with over 200 injured. Due to external causes, suicide or hunger strike, 24 members and sympathizers of the RAF lost their lives.

The RAF, in its self-image a communist, anti-imperialist urban guerrilla based on the South American model similar to the Tupamaros in Uruguay, was founded in 1970 by Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Horst Mahler, Ulrike Meinhof and others. Members of all three generations of the RAF numbered between 60 and 80 between the 1970s and 1990s. The RAF cooperated with Palestinian, and later with French, Italian and Belgian terrorist groups.

A series of attacks in September and October 1977, known as "Offensive 77", intended to free imprisoned first-generation RAF members, led to a crisis in the Federal Republic known as the German Autumn. It ended with the suicides of the imprisoned leaders of the first generation of the RAF in Stuttgart Prison on the so-called night of death in Stammheim.

The second-generation terrorists responsible for most of the acts after 1972 were mostly in prison by the mid-1980s, had gone into hiding abroad or had met their deaths. Various attacks of the late RAF, including nine murders committed by the third and last generation, have not been solved to this day. In 1991 the RAF committed its last murder, in 1993 its last attack, and in 1998 it declared its self-dissolution. In June 2011, the last RAF member was released from prison. The search is still on for four former members.

The confrontation with the RAF had considerable socio-political consequences. It led to the development of dragnet searches and the passing of a series of anti-terror laws by the German Bundestag. The events are the basis of a large number of non-fiction books, television documentaries, feature films, plays and novels, published in Germany and abroad.

Logo of the RAF: a HK MP5 submachine gun in front of a red star

Overview

The RAF was initially known as the "Baader-Meinhof Gang" or the Baader-Meinhof Group. In common use since about the mid-1970s is their self-chosen name, referring to the Soviet Red Army, "Red Army Faction". In addition to the pronunciation of the abbreviation as "Err-A-Eff", one also hears the pronunciation "Raff".

Several generations can be distinguished between which there was little or no continuity of personnel. The essentially three generations also differ in terms of organisational structures and changes in theory and practice. Nevertheless, the generation model represents a simplification.

The number of members of the so-called hard core active in the underground of all three generations amounted to between 60 and 80 persons between the 1970s and 1990s. During the entire period, 914 people were convicted of supporting the RAF and 517 of membership.

In their terrorist attacks or hostage-taking, RAF members murdered 33 people and more than 200 suffered injuries. An exchange of fire that took place in Zurich in 1979 between police officers and members of the RAF ended fatally for Edith Kletzhändler, a passer-by who happened to be present. In retrospect, it was impossible to determine whether the fatal projectile came from the police or the RAF. For this reason, Kletzhändler is often counted as the thirty-fourth victim of the RAF. In addition, 27 members and sympathizers of the RAF died during its existence. Of these, twelve were shot dead, five died in explosions, seven by suicide, one died as a result of a tumour and two died in a traffic accident. The police shot four uninvolved persons by mistake during arrest attempts.

In 2007, Der Spiegel estimated the value of the property damage caused by RAF attacks at the equivalent of 250 million euros. The laws passed between 1974 and 1977 in response to the RAF crimes interfered with the personal rights of all German citizens and are still in force today.

26 RAF members were sentenced to life imprisonment. On the occasion of petitions for pardon, there were regular and sometimes heated debates in the German public about how to deal with the former terrorists. In June 2011, Birgit Hogefeld, the last former member, was released from prison.

Four former members are still being sought today. Daniela Klette, Ernst-Volker Staub and Burkhard Garweg were never caught. Friederike Krabbe was last suspected to be in Baghdad. The whereabouts of three others remain unclear. Ingeborg Barz and Angela Luther have been missing since 1972, Ingrid Siepmann since 1982. The arrest warrants have been lifted.

Previous story

In the 1960s, a generation grew up in the Federal Republic that took a critical view of their parents' behavior during National Socialism. Many also fundamentally questioned capitalism, parliamentary democracy and bourgeois ways of life. Reinforced by the U.S. civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, a hostile attitude toward U.S. policy emerged in sections of society. In the large university cities of Western Europe, there were demonstrations by students against U.S. policy, often raising other issues as well.

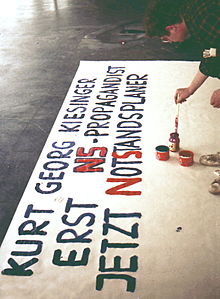

The West German student movement of the 1960s had a formative influence on the RAF. With it, the extra-parliamentary opposition (APO) emerged. A substantial part of the APO's criticism was directed against the emergency laws, which were passed by the first Grand Coalition in the German Bundestag on 30 May 1968 and added an emergency constitution to the Basic Law. Protests, some of them massive, had been rejected by both major parties and could not prevent their passage. In addition, the past of Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger, who had been a member of the NSDAP and an employee of the Foreign Office at the time of National Socialism, polarized the debate. It came to the action of Beate Klarsfeld, who slapped Kiesinger on 7 November 1968 at the CDU party conference in Berlin in front of running television cameras and called a "Nazi".

When the student Benno Ohnesorg was shot by police officer Karl-Heinz Kurras during the demonstration on June 2, 1967 in West Berlin against the Shah of Persia, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, this marked a turning point. Attempts by the authorities to cover up the incident contributed to a further escalation of the already tense situation. On April 11, 1968, an assassination attempt was made on one of the movement's spokesmen, Rudi Dutschke, who barely survived with serious injuries. From 1969 onwards, however, the APO began to break up into many groups, some of which were violently divided. The more politicized youth perceived the end of the movement as a defeat and tried to realize their political ideals in other ways. Many became members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) or attempted the march through the institutions in other ways.

In the following years, however, a militant part also developed out of the protest movement, from which the first generation of the RAF and later the 2nd June Movement (1972), the Revolutionary Cells (1973) and the Red Zora (1977 at the latest) developed. The RAF saw itself as part of international anti-imperialism and believed that the "armed struggle" against so-called "US imperialism" had to be waged in Western Europe as well. Its operations were tactically oriented in the first years to those of the guerrillas in South America. In parts of the former student movement, the K-groups and from other circles of the population there was initially sympathy for the group. This was expressed, for example, in support campaigns and a widespread, semi-legal logistics of supporters, especially through the Red Help. The list of prominent defenders of the first generation is also an indication of this. Due to their radicalism, the second generation had largely lost this basis and operated as a secret, militant and isolated group even more remote from socio-political developments in the Federal Republic.

The Nazi past of the Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger and the passing of the emergency laws led to protests in 1968.

Search within the encyclopedia